Second Annual BRICS Economic Think Tank Forum, Beijing

Rolf Strauch, Member of ESM Management Board

"Towards a stronger Global Financial Safety Net: Lessons from euro area programmes"1

Speech at the second annual BRICS Economic Think Tank Forum

Beijing, 12 December 2015

Dear conference organisers – Mr. Daokui Li and Mr. Marc Uzan,

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure for me to participate in this panel alongside such distinguished fellow speakers.

Let me start with a quotation from Confucius: "The exemplary person pursues harmony, not sameness." Harmony in diversity is a major theme in Confucianism, which echoes well the topic of my speech today – perspectives for a better IMF-RFA (Regional Financial Arrangements) cooperation where each institution has its own strengths and merits.

Back in 2010, in the middle of the global financial crisis, G20 countries agreed on the strengthening of a multi-layered Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) at their Seoul Leaders’ Summit. This reform proposal aimed at mitigating the effects of the systemic crisis and limiting cross-country contagion. Since then, the IMF’s available lending resources were doubled, new precautionary instruments were designed, and large regional resources were mobilised, most notably in Europe. In fact, alongside the IMF, the newly established RFAs constitute a solid line of defence to safeguard global financial stability.

An effective GFSN requires cooperation between the IMF and RFAs, and among RFAs. Close coordination effectively increases the overall size of the financial envelope available to countries in distress. Coordination failure, in turn, would lead to a fragmented, ineffective GFSN, which could face moral hazard problems. Therefore, the G20 endorsed in 2011 six non-binding principles of cooperation between the IMF and RFAs, which provided a foundation for developing more operational guidance.

Euro area programmes have provided a concrete example of how RFAs can work with the Fund. In my remarks, I would thus like to focus on this European experience to illustrate how the IMF and RFAs could collaborate, although it has to be acknowledged that RFAs have different legal provisions governing their relationship with the IMF. Any lessons must, therefore, be translated into different contexts. In addition, the cooperation among RFAs is another important issue that I will not address. I am sure the panel will explore some aspects of it during our discussion.

1. Elements of successful cooperation – commonalities and complementarities

During the recent euro area crisis, the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) were created to assist our Member States facing financial strains. We have been working closely with the IMF throughout our five programmes (i.e. Ireland, Portugal, Greece, Spain and Cyprus) and alongside the European Commission and the European Central Bank. There are important commonalities and complementarities supporting the successful cooperation.

First, cooperation has been based on a deep political commitment by European countries and the IMF. The cooperation of European institutions and the IMF is a political sine qua non among European countries for the approval of a financial adjustment programme. The founding documents of the ESM embody this view. Recital 8 of the ESM Treaty stipulates that "[t]he active participation of the IMF will be sought, both at technical and financial level. A euro area Member State requesting financial assistance from the ESM is expected to address, wherever possible, a similar request to the IMF." In turn, the IMF has made a strong commitment to engaging in programme financing alongside the European institutions.

Second, cooperation is based on a similar programme approach and agreed policy conditionality. The EFSF and ESM share a similar approach with the IMF on crisis resolution. We provide liquidity support to countries facing financial distress on the back of an adjustment programme, which aims at reducing macroeconomic imbalances and structural weaknesses in the requesting country. In all euro area programmes, the European institutions involved and the IMF jointly agreed on political conditionality ex ante. These conditions were enshrined in the legal documents (i.e. the Memorandum of Understanding for European institutions and the letter of intent and Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies for the IMF). This jointly agreed political conditionality provides the requesting country with a clear roadmap of policy reforms needed to bring its domestic economy back on track.

Third, the close collaboration between European institutions and the IMF goes beyond co-financing, while preserving institutional independence. Throughout these programmes, staff members from European institutions and the IMF have always worked closely together on missions during the design, review and post-programme monitoring phases. Information was shared openly. At times, the technical interaction between the IMF and the European institutions, as well as some policy decisions were complicated by their independent procedures and shareholders’ views. Progress could eventually be achieved as all sides made concessions based on their political commitment to cooperation.

Beyond these common factors shaping the cooperation between the EFSF and ESM and the IMF, there are important complementarities. These institutional complementarities help make crisis management successful.

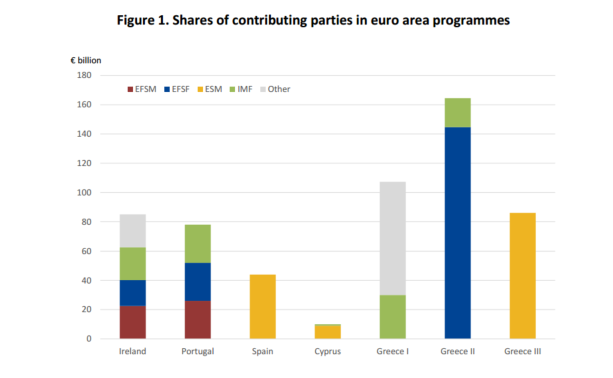

The IMF and the European crisis resolution mechanisms have complementary financial instruments. In practice, the IMF participated in the co-financing for most of the euro area programmes. The IMF’s committed financing reached 26% for Ireland, 33% for Portugal, 28% for the first Greek programme and 10% for Cyprus (see Figure 1). However, the IMF could not financially complement the European programme for Spain, where it does not have specific instruments dedicated to bank recapitalisation. In this case, it provided technical assistance. The ESM has, in addition, the ability to directly recapitalise banks and intervene in the secondary market. This shows a stronger focus on intervention directed towards the financial sector.

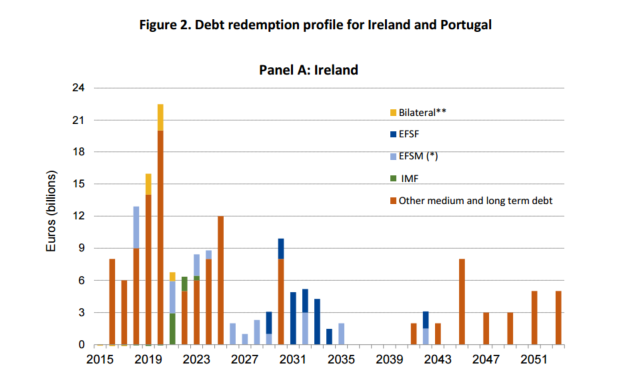

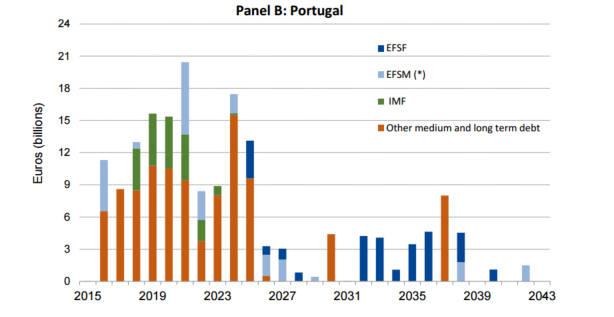

Most importantly, the European crisis resolution mechanisms provided funds at more favourable terms contributing to sustainability. EFSF/ESM lending has in general longer maturities and lower margins. The weighted average maturity reached 20.8 years for Ireland and Portugal, and 31 years for Greece. In comparison, IMF programmes have short-term maturities; the longest repayment period, under the Fund’s Extended Fund Facility (EFF), does not exceed 10 years. Based on these lending terms the European crisis resolution mechanisms lead to higher overall debt maturity. They add fiscal space for the programme country, lower refinancing requirements following the programme, and create an affordable debt structure. This becomes very evident in the case of Greek debt, but it is equally true for Ireland and Portugal (see Figure 2). The EFSF/ESM lending conditions thus facilitate programme countries’ renewed market access.

2. Lessons for the principles of cooperation

What are the lessons to be learned from the European crisis experience for the principles of cooperation between RFAs and the IMF? The European experience mostly confirms the validity of the principles that the G20 formulated. At the same time, it points to modifications and additional elements in appreciating complementarities.

There must be consistency in the programme conditionality that the RFAs and the IMF set, while keeping the independence of each institution. This is a critical point as there has been quite some concern about programme shopping. Consistent conditionality directed at overcoming imbalances and structural weaknesses maximise the synergies among different institutions, and ultimately the success of a programme. Conflicts in programme objectives could indeed divert resources and attention from key reform priorities.

Financial terms of the assistance that different institutions provide can, however, vary and even successfully complement each other in resolving crises. These differences do not have to be a source of arbitrage and facility shopping if the coordination ensures joint RFA and IMF financing and policy conditionality. In the case of Ireland, the set of lenders even included additional bilateral support provided under different financial terms. The concessional lending provided by European crisis resolution mechanisms goes beyond the standard IMF terms and has made a significant contribution to overcoming the crisis.

Finally, a strengthened and well-structured cooperation between the IMF and RFAs will deliver a positive feedback loop among the institutions involved, helping them improve their own policy frameworks.

On the one hand, RFAs have much to learn from the IMF’s best practice for both crisis resolution and prevention. European institutions have learned and will continue to learn from the IMF in important areas beyond designing crisis resolution programmes, such as preventive identification of warning signals, ex post and independent programme evaluation and consistency checks for policy recommendations across programmes.

On the other hand, the conditions of RFAs' financial assistance should also lead the IMF to rethink its current crisis resolution and lending framework. For instance, the Fund needs to reconsider the time horizon used in its Debt Sustainability Analysis given the long-term nature of ESM lending. Moreover, IMF staff have to adjust to the layered policy responsibilities in a monetary union, where some policy areas are shifted to the union level. As such, they are not subject to the standard setup of policy recommendations. Finally, economic effects may differ substantially in a highly integrated monetary union and common market, which require a recalibrated assessment of systemic consequences under financial stress.

Let me conclude by going back to the Confucius’ saying. The rich institutional and operational cultures in RFAs and the IMF reflect diversity. At the same time, we are committed to working jointly towards a strong and harmonious Global Financial Safety Net - "The exemplary person pursues harmony, not sameness."

Thank you for your attention.

Note: All figures indicate the financial commitment, which may differ from actual disbursements. Other financing sources for Ireland include Sweden, Denmark, the United Kingdom and the Irish Treasury and National Pension Reserve Fund. Other financing sources for Greece I are the pooled bilateral loans from European countries. The IMF is expected to contribute to the current programme for Greece. The ESM financing amount for Greece III will be reduced by the size of the IMF facility. Source: ESM staff calculation

Note: * EFSM loans are subject to a 7-year extension. It is, therefore, not expected that Portugal will have to refinance any of its EFSM loans before 2026 and Ireland before 2027. ** The bilateral loans for Ireland were provided from the United Kingdom, Sweden and Denmark. Source: National Debt Management Offices, ESM staff calculation

Author

Contacts