22. A ‘big mistake’: Greece’s second rescue stumbles

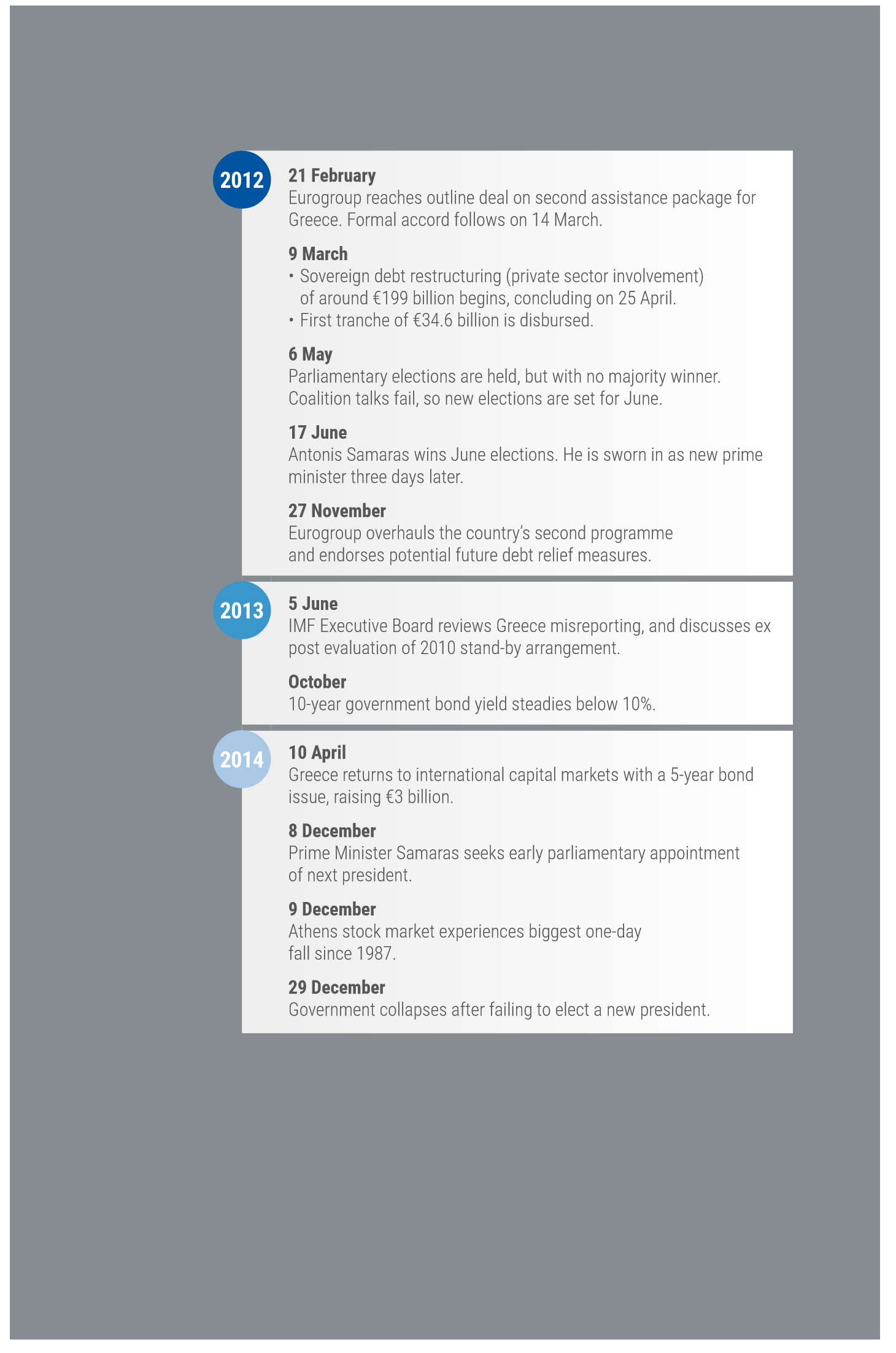

With former ECB Vice President Papademos installed as interim prime minister in November 2011, Greece quickly began readying itself for a second rescue programme. First on the agenda was the proposed private sector debt exchange. An effort to put a deal together in late 2011 had collapsed, so negotiations needed to start again on a bigger scale[1]. In February 2012, the Greek government announced that it had hammered out the terms with representatives of private sector bondholders, clearing a key hurdle.

By the end of the month, the other pieces were in place. As with all euro area aid programmes, the second rescue agreement came with conditions that would need to be implemented over time. These included pension system reform, higher taxes, minimum wage cuts of more than 20%, the scrapping of 150,000 public sector jobs, and more flexible types of employment. Once Greece had signed up to these conditions and permanent on-the-ground monitoring of its compliance by the troika, the Eurogroup signed off on the follow-up programme[2].

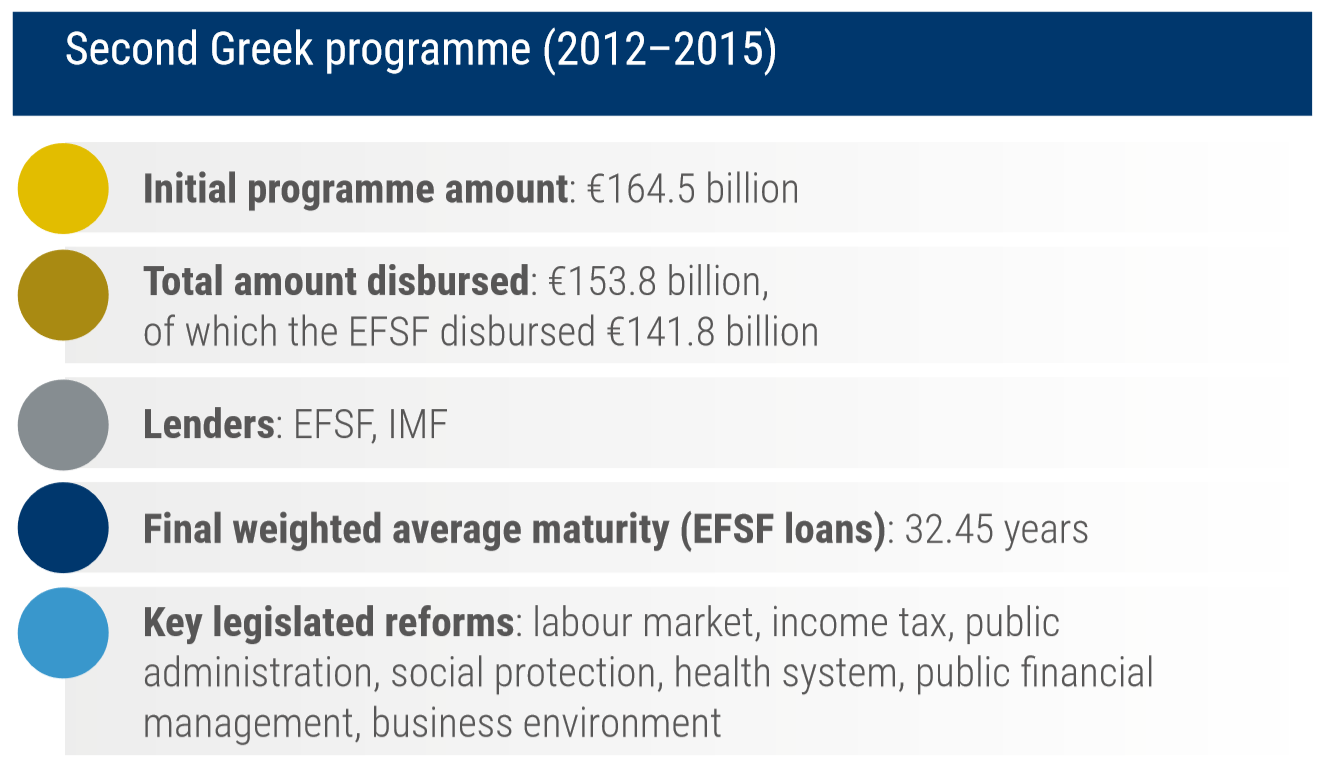

Formal approval came on 14 March 2012[3]. In contrast to the ad hoc nature of Greece’s first rescue, this second rescue came from the now fully operational EFSF. Totalling around €130 billion plus leftover IMF and EU funds from the first aid effort, the funds were originally scheduled for disbursement between 2012 and 2014, although as with many of Greece’s accords with the euro area, this schedule would be renegotiated later in the year. The IMF approved an extended fund facility for Greece and the release of its first instalment on 15 March.

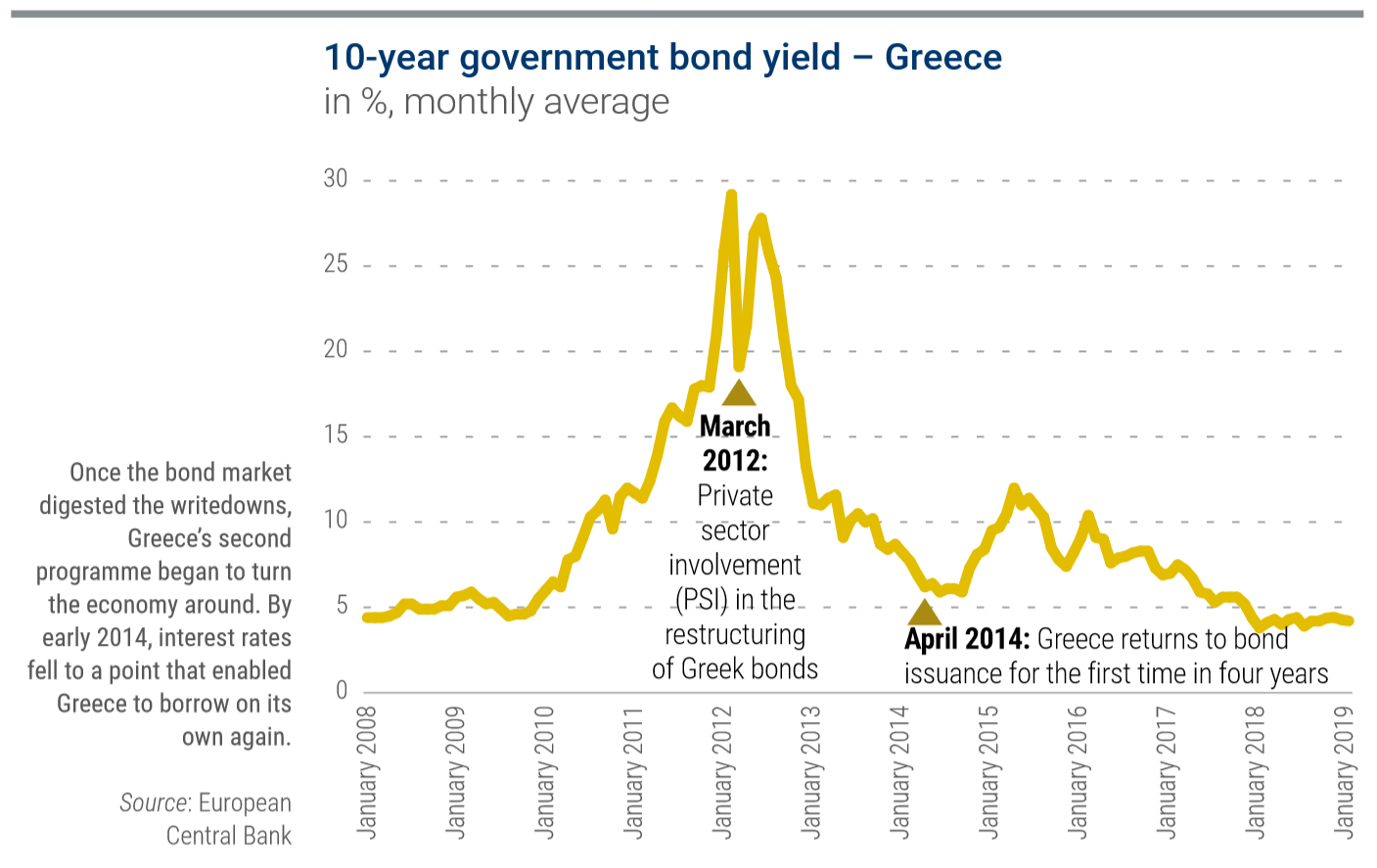

On 9 March, the private sector debt exchange deal, or private sector involvement, got underway. The writedowns went ahead on a ‘voluntary’ basis, sparing Greece from a disorderly default and the ensuing chain reaction of financial consequences. Participating investors accepted writedowns of 53.5% of the principal amount of their existing bonds, in exchange for a package of new Greek bonds, short-dated EFSF securities, and extra securities linked to Greece’s GDP growth[4]. Out of a total of €206 billion in bonds eligible for the offer, approximately €199 billion, or 96.9% were exchanged, easily surpassing the 75% minimum needed for the operation to go ahead[5].

It was the biggest sovereign writedown in history, reducing Greece’s outstanding debt by about €107 billion[6]. Yet it went through smoothly, because markets had had plenty of time to prepare for it. Backers of the haircuts hailed a turning point in the crisis response. Those who predicted the policy would trigger a financial market crash ‘have been proven wrong. Nothing bad happened,’ former German Finance Minister Schäuble said. ‘This is an important principle, as it ensures that investors take risks into consideration, even when purchasing government bonds, and allows free-market mechanisms to highlight any need for corrective measures.’

Focus

€15 billion and 10 minutes to spare

Behind the scenes of the biggest sovereign debt restructuring in history, which began on Friday 9 March 2012, EFSF lawyers, the lending team, and debt managers saw to it that the transaction would go through without a hitch. Figuring out the details required everyone to work together at top speed.

The bonds had to be in the Greek settlement system before the weekend so that the first set of investors could exchange their old bonds on Monday for the new EFSF-provided, as well as other, securities[7]. The size and scale were far beyond normal market operations. ‘This was a very unique exercise in high amounts with plenty of bondholders,’ said Ruhl, the EFSF head of funding. And the stakes were enormous – if anything went wrong, it could destabilise banks across Europe.

‘The private sector involvement was agreed to take place over the weekend, so we had to deliver the bonds by Friday evening,’ Ruhl said. The closing time was 17.30 for the settlement process, but the bonds couldn’t move until all of the authorisations were in place, which depended on Greece delivering a final signature on Friday afternoon.

To get the operation started, Greece had to create about €15 billion in Greek government bonds – but the timing was incredibly tight, according to the rescue fund’s Chief Economist Strauch. ‘There was a call at 17.00 where I told them essentially: if you don’t move so we can do this now, the transaction will not take place,’ Strauch said. ‘They had to run to make it happen.’

A broken fax machine at the Greek finance ministry added to the suspense of what was already a race against the clock. The EFSF sent over a document for the Greek officials to sign, but the finance ministry couldn’t fax it back. In a scramble, the officials found a working machine at Greece’s debt management office and faxed the signature from there. The team held its breath.

‘We managed to send our bonds at absolutely the last minute, to an account at the Bundesbank, and from there they would go to the Bank of Greece,’ Strauch said. ‘There was the back and forth with the signatures and the clock was ticking. I think only 10 minutes before, at 17.20, I called the guy in Frankfurt to hit the button and send them over to Greece […] and the bonds arrived.’

The private sector involvement exercise marked the first use of funds from Greece’s EFSF programme. Policymakers then approved a tranche of cash payments, which were paid out in several instalments between March and June. Around the middle of the year, however, things began to slow down.

Greek voters returned to the polls in May 2012, but no party won a parliamentary majority. After a follow-up election six weeks later in June, it became Antonis Samaras’s turn to get a coalition up and running. To be his finance minister, Samaras turned to Yannis Stournaras, a university economics professor who also ran a private sector think tank.

Stournaras had a technocratic background and was acquainted with many of the key players from his time on the EU committee of finance ministry deputies in the late 1990s. When Greece was preparing to join the euro, he had sat between future EFSF CEO Regling and future ECB President Draghi under EU protocol order.

‘The fact that I knew all of these people helped a lot,’ Stournaras said. ‘I had a strong opinion about what should be done – I said, first of all we have to restore credibility before we ask for anything.’

As soon as the new government was in place, talks began in July 2012 about how to push ahead with the programme, which had stalled during the run-up to the elections and subsequent change in government. In October, European finance ministers paired encouraging words about Greece’s determination to cut its budget and overhaul its economy with a requirement that it commit to 89 policy steps[8]. It took until a series of fraught meetings in November for Greece to renegotiate the programme terms and make another attempt at getting its debt under control.

Those negotiations slowed the fiscal adjustment pace, providing for more achievable primary surplus targets. The target for 2014, for example, was reduced to 1.5% of GDP from 4.5%[9], with a goal of reaching the more challenging target in 2016.

Stournaras said the ‘more realistic’ fiscal targets improved the prospects of turning the economy around. In setting the targets, Greece, the European Commission, and the IMF repeatedly clashed over how far and how fast Greece would need to reduce its spending. The debates would play out repeatedly through the end of Greece’s second programme and, ultimately, to its third rescue in 2015.

Greece had to wait until December 2012 for its next EFSF disbursement. Even when finance ministers signed off on a tranche, they divided it into smaller[10] sums that would be handed out piecemeal as Greece tackled its demanding to-do list.

The EFSF was always standing by with the money as soon as its release was approved. Thanks to the diversified funding strategy, the firewall no longer had to rush into the markets every time a disbursement loomed. Instead, it could be a more regular and predictable issuer, satisfying investors as well as programme countries.

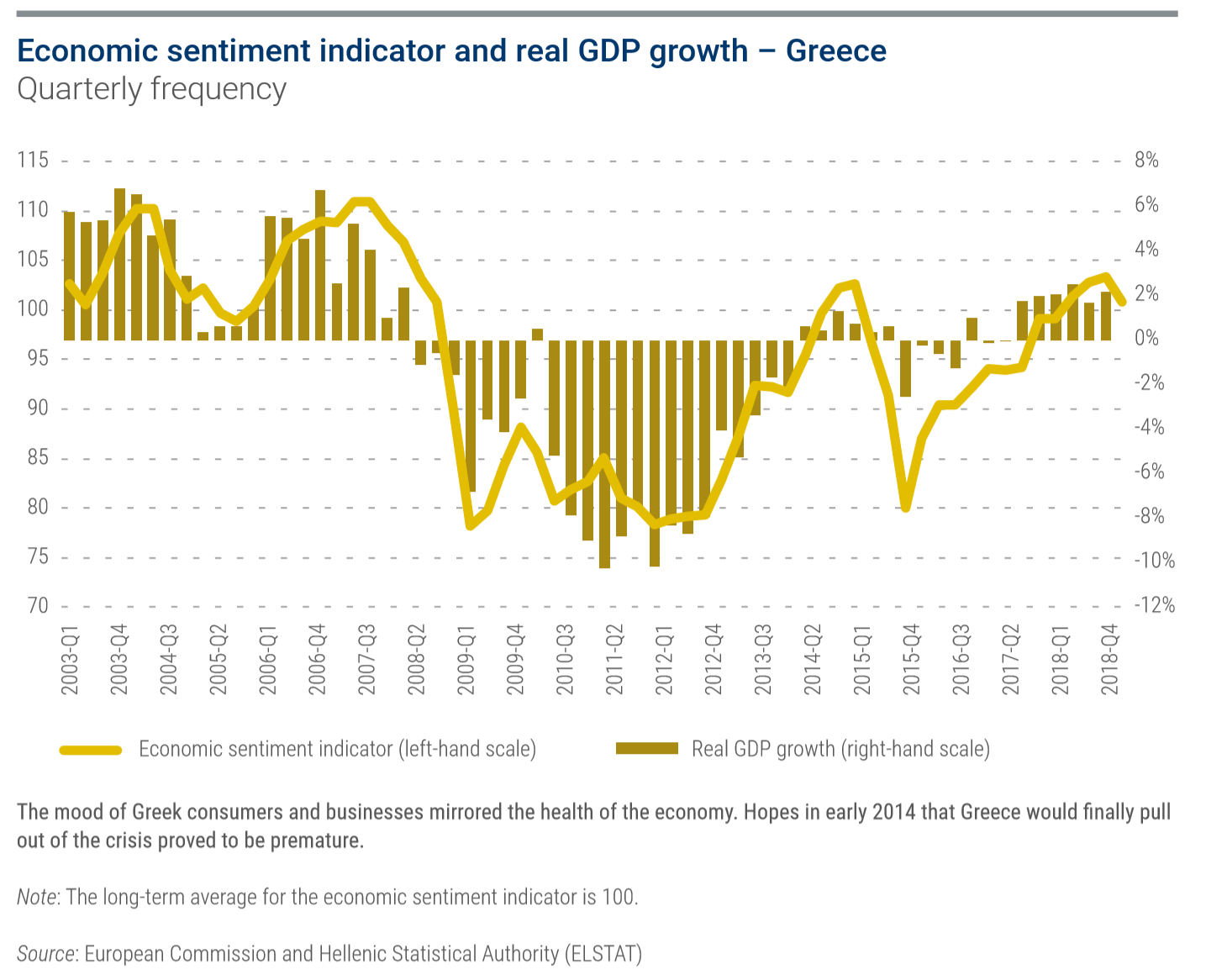

For 2013 and the first half of 2014, the second programme moved along largely as designed. In 2013, the EFSF made eight disbursements to Greece, totalling €25.3 billion, and for a while in 2014, Greece’s prospects seemed to be brightening. Full- year GDP growth was 0.7%, turning positive for the first time since 2007[11]. Ten-year bond yields steadied at around 6% in the summer of 2014. The government made a cautious return to the market on two occasions, and posted a dramatic budget turnaround. Meanwhile, the banks raised private capital and issued bonds. In early 2014, the Commission said Greece had achieved a €1.2 billion primary surplus in 2013 as a result of its fiscal overhaul[12].

Around mid-2014, Greece seemed to have a chance of wrapping up its programme, as both Ireland and Portugal had done. ‘At one point it looked as if they could get out, they could get a credit line, and growth was back,’ Strauch said.

But reform momentum slowed in the second half of the year, as Greece stumbled under the weight of political turmoil and six years of recession. Stournaras became governor of the Greek central bank in June 2014 and was replaced at the finance ministry by Gikas Hardouvelis.

Greece also needed to convince the IMF that its finances were on a sustainable path for at least 12 months, a normal requirement for every IMF disbursement. The IMF had a different approach to debt sustainability from the euro area, but at the time the euro area institutions did not want to break ranks inside the troika. So the review was never concluded, meaning key disbursements didn’t take place.

‘The biggest error was made in 2014,’ said Stournaras. ‘It was a big mistake that the review didn’t close, on account of a fiscal gap of a few million euros.’

In Stournaras’ view, the fiscal shortfall didn’t exist, depending on how you ran the numbers. The primary surplus target at the time was 3% of GDP for 2015 and 4.5% for 2016–2017[13].

But Rolf Strauch of the ESM recalls that the failure to close hinged as much on the slowdown in structural reforms as on the fiscal gap. ‘Towards the second half of 2014, the Samaras government had exhausted its political capital and was basically unable to move forward any significant structural reform. The government had, therefore, fallen behind some benchmarks agreed with the IMF, which were effectively not met. On the European side, the performance gap was smaller, but also not entirely confined to the budget issue.’

Once again, personalities, stress, and emotion influenced the discussions, and ultimately sank any prospect of compromise. Relations were fraying. Some European policymakers felt that Greece rarely delivered on its promises, while many Greek citizens regarded the troika as all but impossible to satisfy. It was a vicious cycle that made the talks even harder at times.

‘The game was that they were sceptical about the Greek politicians’ ownership of the programmes,’ Stournaras said. ‘They asked for more and more, thinking that we would implement only a percentage of it. But that was a mistake. Austerity is austerity.’ He added: ‘The mistake was on both sides. His peers thought that Samaras was bluffing.

But he was not. The parliamentary group, consisting of members of parliament from two parties, New Democracy and Pasok, supporting the government, could not be convinced that further austerity measures were necessary.’

Towards the end of the year, Samaras felt he no longer had the political backing needed to carry out the last round of budget cuts and structural measures required to secure troika approval. Undercut by faltering support at home, he sought leniency from EU leaders, but they refused to let Greek domestic politics dictate the course of the review. At that point, Samaras saw no choice but to go to the polls.

Strauch said: ‘The last month Samaras was in power, he could no longer push through the kind of significant reforms that we were asking for. That was the stalemate.’

On 8 December 2014, Samaras announced an election for Greece’s largely ceremonial presidency[14]. Political uncertainty spooked the markets – the day after, the Greek stock market plunged 12.78%, the biggest one-day fall since 1987[15]. The year closed with political deadlock, as Greece’s parliament failed to choose a new president and Samaras’s government collapsed.

On 25 January 2015, Greece held a parliamentary election[16], with Samaras representing both continuity and further belt-tightening, and the Syriza party representing a break with the old and resistance to further spending cuts[17]. As the clock ran out on the second assistance programme in 2015, Greece and the euro area would face their biggest test yet.

Continue reading

[1] Global Restructuring Review (2017), ‘Overview: Restructuring of Greek sovereign debt’, 10 March 2017. https://globalrestructuringreview.com/benchmarking/the-european-middle-eastern-and-african-restructuring-review-2017/1137879/overview-restructuring-of-greek-sovereign-debt

[2] Eurogroup statement, 21 February 2012. https://www.esm.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2012-02-21_eurogroup_statement_bailout_for_greece.pdf

[3] Statement by the President of the Eurogroup, Jean-Claude Juncker, 14 March 2012. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/128941.pdf

[4] Reuters (2012), ‘Factbox: Terms of the Greek bond swap laid bare’, 7 March 2012. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-greece-swap-factbox/factbox-terms-of-the-greek-bond-swaplaid-bare-idUSTRE8260K620120307

[5] Greece, Ministry of finance (2012), Press release, 11 April 2012. http://www.pdma.gr/greekbonds/index.php/2012-05-28-15-51-31/2012-05-28-15-52-10/2012-05-28-15-54-7/2012-05-28-15-55-55/2012-05-28-16-01-51/category/24-press-releases?download=412:11-april-2012

[6] ESM (n.d.), ‘What was the private sector debt restructuring in March 2012?’. https://www.esm.europa.eu/content/what-was-private-sector-debt-restructuring-march-2012

[7] Greece, Ministry of finance (2012), Press release, 11 April 2012. http://www.pdma.gr/greekbonds/index.php/2012-05-28-15-51-31/2012-05-28-15-52-10/2012-05-28-15-54-7/2012-05-28-15-55-55/2012-05-28-16-01-51/category/24-press-releases?download=412:11-april-2012

[8] ‘Eurogoup meeting – October 2012: Press conference – Part 1’, Video, 8 October 2012. https://tvnewsroom.consilium.europa.eu/events/eurogroup-meeting-october-2012/press-conference-part-1-210; Bloomberg (2012), ‘EU lauds Greek budget-cutting will, boosting aid prospects’, 9 October 2012. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-10-08/europe-salutes-greek-budget-cutting-will-raising-aid-prospects

[9] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2012), ‘The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece first review – December 2012’, European Economy Occasional Papers 123, p. 3, December 2012. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2012/pdf/ocp123_en.pdf

[10] Ibid., p. 59.

[11] Eurostat (n.d.), ‘Real GDP growth rate – volume’. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tec00115&plugin=1

[12] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2014), ‘The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece – fourth review – April 2014’, European Economy Occasional Papers 192, p. 14, April 2014. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2014/pdf/ocp192_en.pdf

[13] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2012), ‘The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece first review – December 2012’, European Economy Occasional Papers 123, p. 22, December 2012. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2012/pdf/ocp123_en.pdf

[14] Financial Times (2014), ‘Greek premier calls snap presidential election’, 8 December 2014. https://www.ft.com/content/747cdf0c-7f09-11e4-bd75-00144feabdc0

[15] Seeking Alpha (2014), ‘The Greece stock market: This 12% drop came with a warning,’ 9 December 2014. https://seekingalpha.com/article/2743215-the-greece-stock-market-this-12-percent-drop-came-with-a-warning

[16] Euronews (2014), ‘Greek government announces snap presidential vote’, 9 December 2014. http://www.euronews.com/2014/12/09/greek-government-announces-snap-presidential-vote

[17] Reuters (2014), ‘Greece faces early election after PM loses vote on president’, 29 December 2014. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-greece-vote-result/greece-faces-early-election-after-pm-loses-vote-on-president-idUKKBN0K70NH20141229