19. From bailout to bail-in: towards a new programme for Greece

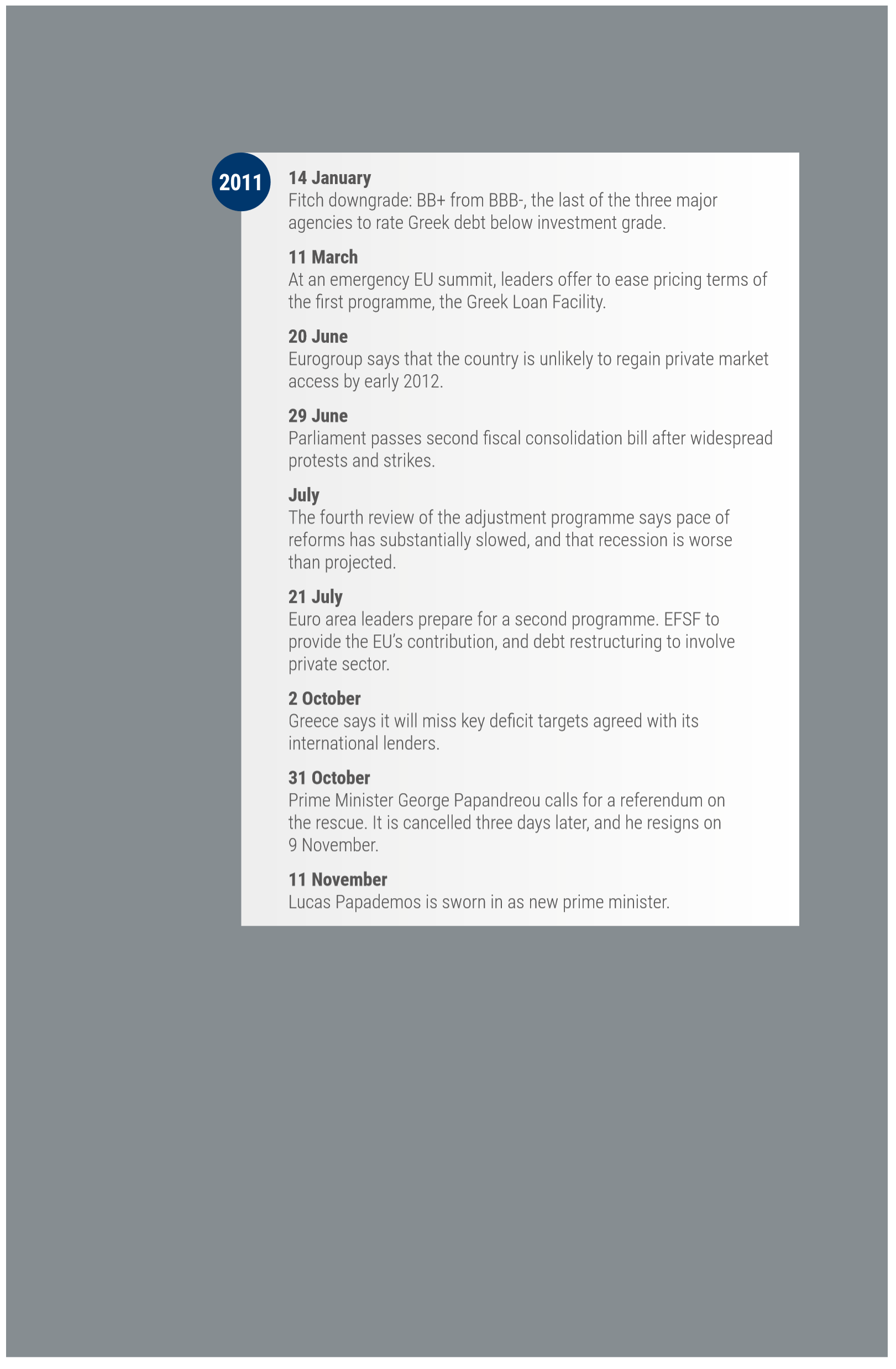

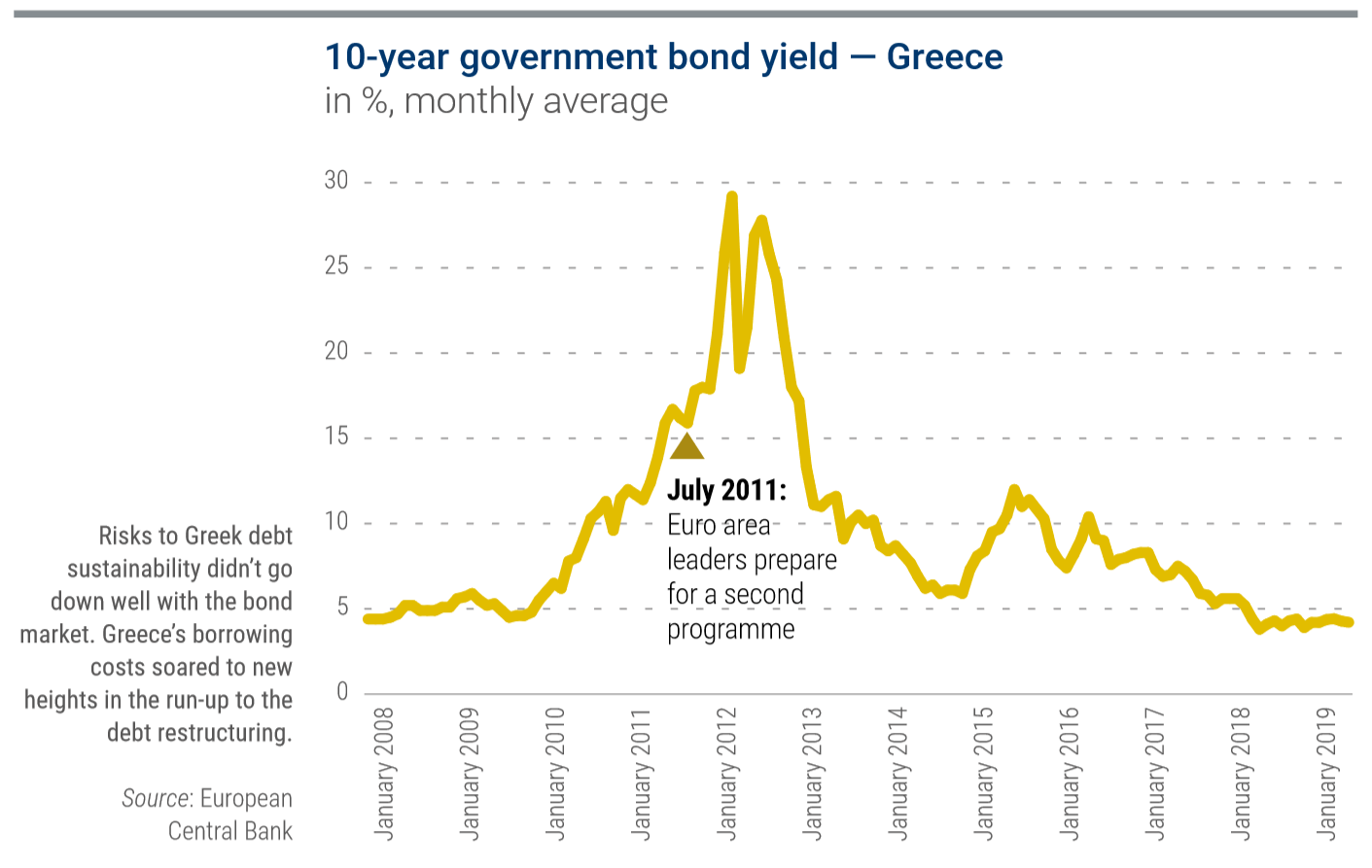

Greece was a recurring concern in the first years of the euro crisis. By January 2011, the three major rating agencies had all reduced Greece’s debt to below investment grade. Credit downgrades continued until, by the end of July, Greece was the lowest-rated country in the world[1], cut off from market financing and left dependent on outside financial help.

European policy debates reflected this slide in market confidence, as optimism evaporated that Greece could emerge from the crisis on its own. Worries about the scope of Greece’s economic challenges – and doubts about whether or not the faltering assistance programme could address them – took centre stage.

Euro area leaders didn’t want to put more money into Greece just to enrich speculators who had bought its bonds. But private investors opposed being forced into forgiving debt owed to them by Greece. In the 2010 push to assemble the first rescue programme for Greece, international authorities had hoped this infusion of funds would be enough to stabilise the Greek situation and prevent contagion.

Disbursements from the first programme, via the Greek Loan Facility, were made in January and March 2011. At an emergency EU summit on 11 March 2011, leaders offered to ease pricing terms[2]. They lowered the rates and extended the maturity of Greek Loan Facility loans – a step that gave Athens more breathing room to manage the tough reforms required.

Only a few months later, matters turned critical again. In conducting the fourth and final review of Greece’s first programme, the troika of institutions – the ECB, IMF, and European Commission – warned in July of a let-up in reform implementation and a worse-than-expected recession[3]. Given the lack of progress, there was less willingness to disburse more of the rescue funds that had become Greece’s lifeline.

Deteriorating finances, a loss of competitiveness, and historically rigid industrial structures plagued the Greek economy. Many professions were stifled by restrictive regulation, making it hard for new entrants to do business. Tax evasion remained a major problem. Greek banks were also struggling to keep up with the challenges facing the economy.

Although Greece succeeded in bringing its deficits down considerably during the first rescue programme with the Greek Loan Facility, the country was still in trouble. The recession deepened.

In retrospect, the IMF pointed to a number of shortcomings in its first Greek programme[4]. ‘Market confidence was not restored, the banking system lost 30 percent of its deposits, and the economy encountered a much deeper-than-expected recession with exceptionally high unemployment,’ the IMF would later describe this period in a 2013 evaluation. ‘The depth of ownership of the program and the capacity to implement structural reforms were overestimated.’ The report also noted that social and political turmoil undermined confidence.

Much of the latter half of 2011 was spent considering how to address Greece’s debt. When leaders acknowledged that Greece would need more money, they also made clear they would refuse to act unless financial markets agreed to absorb some of the costs. Until there was accord on how to do that, leaders weren’t prepared to put more money into solving Greece’s overarching economic problems.

Days before a crucial 20 June 2011 Eurogroup meeting, Greece’s finance ministry underwent a change at the top. Papaconstantinou was replaced as finance minister by Evangelos Venizelos, a political veteran. Whereas Papaconstantinou had been part of the rescue negotiations since Greece’s budget woes first emerged in 2009, Venizelos was brand new to the debt talks, but he was known for political savvy gained over a career that included stints as defence, justice, and transport minister. The hope was that he had the domestic clout to deliver on Greece’s promises, even if he didn’t have as much financial market expertise.

At that June meeting in Luxembourg, euro finance ministers conceded that Greece would not be able to borrow on its own any time soon. ‘[G]iven the difficult financing circumstances, Greece is unlikely to regain private market access by early 2012,’ the Eurogroup said in a statement after the meeting[5].

The admission raised the stakes: more money would be needed, but this time the Eurogroup determined that private sector bondholders would share the costs, which meant forgiving some of the debt Greece owed them. ‘Ministers agreed that the required additional funding will be financed through both official and private sources and welcome the pursuit of voluntary private sector involvement,’ the 20 June statement said. In that same statement, they still held out hope that Greece could avoid a selective default through ‘the pursuit of voluntary private sector involvement in the form of informal and voluntary roll-overs of existing Greek debt at maturity’. Ultimately, the private sector involvement would take place in an exchange of outstanding debt the following year, in which bondholders swapped their existing bonds for new securities with a lower face value.

Despite what the euro area saw as slowing reform momentum, the Greek government pushed through a second fiscal consolidation package that included large spending cuts and tax increases at the end of June to meet its aid requirements. But parliamentary approval generated two days of protests that left hundreds of protesters and police injured. Protests had been a serious concern in Greece ever since demonstrations in May 2010 had left three dead in the wake of the signing of the agreement to initiate the first programme.

The Greek government was under pressure to hold firm to its commitments even as economic conditions worsened and domestic opposition to the reforms rose. The Commission said in its fourth review of the Greek Loan Facility that ‘reform implementation has substantially decelerated.’ It also found the recession to be deeper and more protracted[6]. There was sympathy for the plight of the Greek workforce, suffering from the lengthy recession, tax increases, and high unemployment, but euro area leaders maintained that there was no other way to provide a lasting solution to the country’s years-long drop in competitiveness.

‘These are unprecedented, but necessary, efforts to bring the Greek economy back on a sustainable growth path,’ euro leaders said in a 21 July 2011 summit statement. ‘We are conscious of the efforts that the adjustment measures entail for the Greek citizens, and are convinced that these sacrifices are indispensable for economic recovery and will contribute to the future stability and welfare of the country’[7].

Against this tumultuous backdrop, Greece’s second rescue programme began to take shape. Greece needed a big infusion of cash to pay its bills. At the July summit, euro area leaders agreed to start talks on more aid – provided that bondholders accepted losses in order to reduce Greece’s debt burden[8]. There could be €109 billion available from IMF and European sources, the leaders pledged, but only if Greece stuck to its cuts and bondholders bowed to a ‘voluntary’ restructuring. For it to work, most private holders of Greek bonds would have to participate, even if they had the option not to.

Soon after the summit, talks with bondholders got underway. For its backers, the debt exchange represented an essential step; for its detractors, it spelt financial market heresy. Greek stocks plunged, with the Athens Stock Exchange falling below 1,000 points on 8 August, the lowest in almost 15 years. Bond yields were rising precipitously.

Private investors warned that the proposed debt exchange would leave a catastrophic legacy for Europe, especially given the possibility of further losses in other countries. Josef Ackermann, CEO of Deutsche Bank, said that there were many investors in the US and Asia who would shun euro area bonds under these conditions, according to a 28 November 2011 article in Germany's Spiegel Online. ‘We will be paying a high price for a long time to come for having violated the principle that European government bonds are risk-free,’ said Ackermann, who was at that time chairman of the Board of Directors of the Institute of International Finance (IIF)[9].

IMF and EU officials had laboured with the IIF, a trade group representing the private creditors, to find a way to keep the exchange legally voluntary and thereby forestall an official declaration of default, while reaping enough savings to meet Greece’s debt targets.

Bankers and private sector holders of Greek debt weren’t alone in opposing bond writedowns. Sceptics feared that the debt swap could devastate the euro area’s marketplace credibility. Trichet, former president of the ECB, had negotiated debt relief for underdeveloped countries as head of the Paris Club of creditor countries in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and saw sovereign debt writedowns, as first raised by Germany’s Merkel and France’s Sarkozy in 2010 in Deauville, as extremely dangerous as long as they were perceived as being the general rule for all vulnerable countries. By casting sovereign debt as no longer risk free, he argued, the euro area would undermine its work to rebuild market trust in troubled economies. On the practical side, it could sabotage the health of the very countries it was designed to rescue.

The prospect of imposing losses on bondholders ‘was destroying all of our deterrent, all the deterrent of the EFSF, and also what we were doing with the ESM,’ Trichet later said. He said the euro area was able to stabilise its reputation only when it made clear that debt writedowns for Greece would be a one-off, not a required part of any rescue programme.

Trichet’s resistance was part central banker caution and part European pride, said Lagarde, who had taken over as IMF managing director on 5 July 2011. ‘For him it was just complete nonsense, an absurdity, and a dangerous path,’ she said. ‘He was concerned about the euro because he was the president of the ECB. But, as the former president of the Paris Club, which leads debt restructurings, most often of developing countries, it was just anathema to imagine an advanced country having to restructure its debt.’

Initial hopes of getting a second Greek programme in place by September proved unworkable, making global leaders nervous. On 26 September 2011, US President Barack Obama warned at a local question-and-answer meeting in California’s Silicon Valley that Europe had not done enough to combat contagion, naming Greece as the possible trigger for the next systemic shock. ‘They have not fully healed from the crisis back in 2007 and never fully dealt with all the challenges their banking system faced. It’s now being compounded by what’s happening in Greece,’ Obama said. ‘They’re going through a financial crisis that is scaring the world. And they’re trying to take responsible actions, but those actions haven’t been quite as quick as they need to be’[10].

Back in Europe, fears of a Greek exit from the euro, stoked by the Luxembourg castle meeting in May, became more prevalent[11]. In October, the government in Athens said Greece would not be able to meet the 2011 or 2012 deficit targets it had agreed with its international creditors because of the unexpected harshness of the recession.

Crisis diplomacy in late October focused on the bond writedowns, seen as the key to unlocking more aid for Greece. To win the investment community’s acceptance of the unprecedented step and prevent it from sapping confidence in the bonds of other distressed countries, euro area leaders made the case that the Greek restructuring was a one-off due to the ‘exceptional’[12] nature of Greece’s economic troubles.

‘All other euro countries solemnly reaffirm their inflexible determination to honour fully their own individual sovereign signature and all their commitments to sustainable fiscal conditions and structural reforms. The euro area Heads of State or Government fully support this determination as the credibility of all their sovereign signatures is a decisive element for ensuring financial stability in the euro area as a whole’[13], the leaders said in a summit statement on 26 October 2011.

In Greece’s case, the leaders said that bondholders would have to take a roughly 50% haircut as part of a new aid package. The leaders set a goal of end-2011 to sign off on the programme, with the bond swap scheduled for early 2012. Haunted by the threat of a market panic, the October summit statement acknowledged the global worries and proposed what was intended to be a comprehensive plan because ‘further action is needed to restore confidence’[14].

At this point, Greek Prime Minister Papandreou surprised everyone on 31 October 2011 by calling for a referendum on the outline of the rescue plan[15]. At a 3 and 4 November summit of the Group of 20 countries in Cannes, France, Merkel and Sarkozy led the euro area in laying down the gauntlet, telling the Greek leader that his referendum would in effect be a yes or no vote not just on the rescue, but on Greece’s euro membership.

When, on the eve of the summit, Papandreou arrived unexpectedly to inform Sarkozy and Merkel about the referendum plan, they opposed it immediately, the IMF’s Lipsky said. ‘The impression was left that in addition to objecting to the proposal to hold a referendum, the two key leaders had lost confidence in him personally.’

Continue reading

[1] Reuters (2011), ‘Greece falls to S&P’s lowest rated, default warned’, 13 June 2011. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-greece-ratings-sandp/greece-falls-to-sps-lowest-rated-default-warned-idUSN1312685920110613

[2] Statement by the Heads of State or Government of the Euro area – 11 March 2011, The European Council in 2011, January 2012, p. 32. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/21347/qcao11001enc.pdf

[3] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2011), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece fourth review – spring 2011’, European Economy Occasional Papers 82, July 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2011/pdf/ocp82_en.pdf

[4] IMF (2013), Greece: ex post evaluation of exceptional access under the 2010 stand-by arrangement, IMF staff country reports, 5 June 2013. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2016/12/31/Greece-Ex-Post-Evaluation-of-Exceptional-Access-Under-the-2010-Stand-By-Arrangement-40639

[5] Statement by the Eurogroup on Greece, Brussels, 20 June 2011. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-11-426_en.htm?locale=en

[6] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2011), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece fourth review – spring 2011’, European Economy Occasional Papers 82, p. 9, July 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2011/pdf/ocp82_en.pdf

[7] Statement by the Heads of State or Government of the Euro area and EU Institutions, 21 July 2011. http://feelingeurope.eu/Pages/euro%20area%20statement%2021-07-2011.pdf

[8] Ibid.

[9] Spiegel online (2011), ‘A continent stares into the abyss’, 28 November 2011. http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/euro-zone-on-the-brink-a-continent-stares-into-the-abyss-a-800285-2.html

[10] US, Office of the Press Secretary (2011), ‘Remarks by the president in town hall with Linkedin’, 26 September 2011. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/09/26/remarks-president-town-hall-linkedin

[11] Spiegel online (2011), ‘Greece considers exit from euro zone’, 6 May 2011. http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/athens-mulls-plans-for-new-currency-greece-considers-exit-from-euro-zone-a-761201.html

[12] Euro summit statement, 26 October 2011. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/125644.pdf

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Financial Times (2011), ‘Greece calls referendum on EU bail-out’, 31 October 2011. https://www.ft.com/content/68748490-03f5-11e1-98bc-00144feabdc0

[16] Reuters (2011), ‘Greek PM ready to go, dump referendum, for euro deal’, 3 November 2011. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-g20/greek-pm-ready-to-go-dump-referendum-for-euro-deal-idUKTRE7A20DG20111103

[17] New York Times (2011), ‘Greek leader calls off referendum on bailout plan’, 3 November 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/04/world/europe/greek-leaders-split-on-euro-referendum.html