36. Moving towards Grexit: at the cliff’s edge

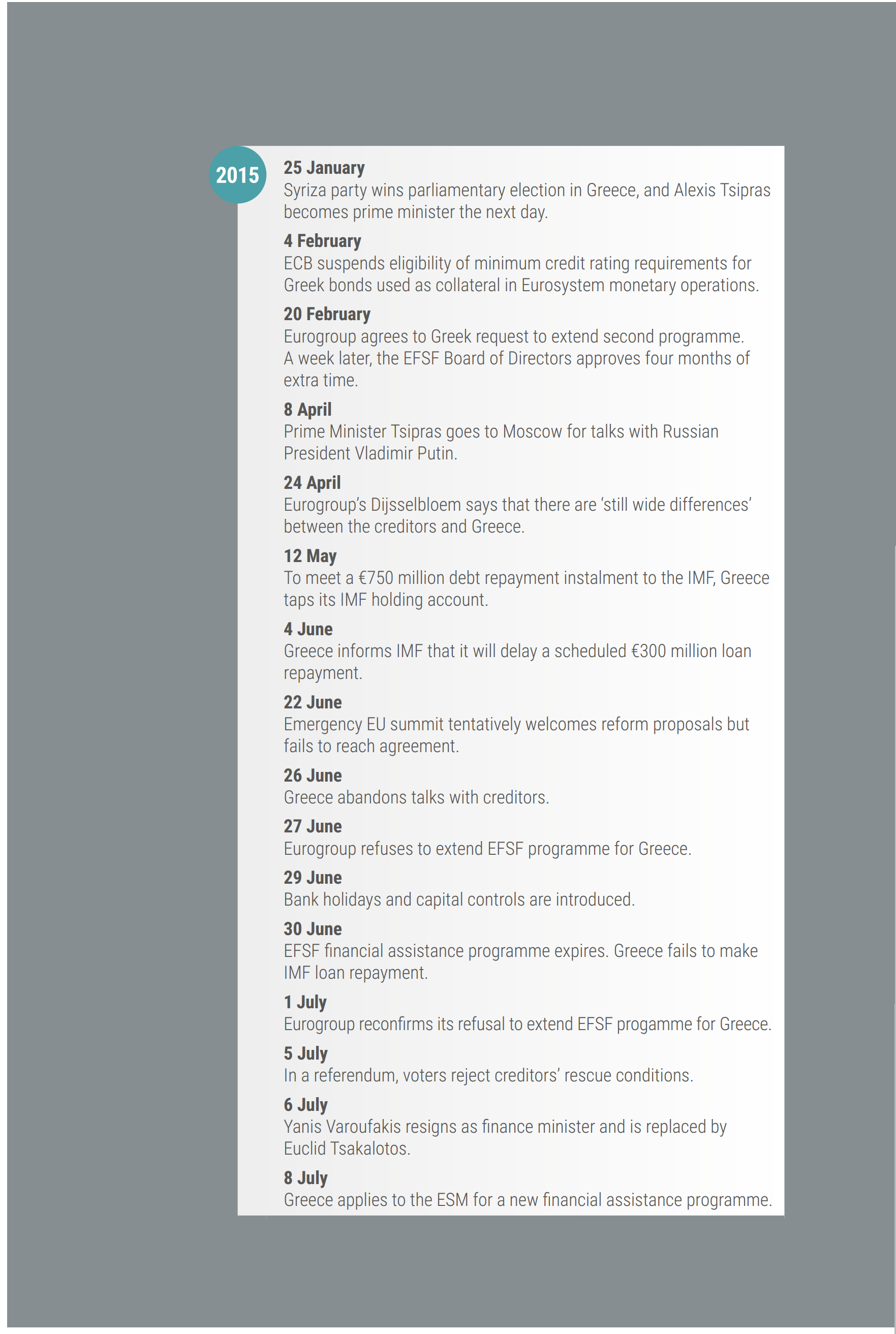

Greek voters, bitter over the wage and pension cuts required by the troika, sought change via Syriza, the party led by the charismatic newcomer Alexis Tsipras. He became prime minister on 26 January 2015, with one month left in the second rescue programme and no prospect of an agreement on the final review in sight[1].

Instead of plunging into negotiations with the creditors, however, Tsipras weighed his options. The Eurogroup realised that the newly installed government would need time to figure out a strategy. But Syriza was initially adamant that it wouldn’t ask for an extension to the existing rescue, since the whole premise of its campaign was to expel the troika.

The new government was making a good-faith effort to reflect Greek voters’ frustration at the effects of the economic adjustment programmes, said Euclid Tsakalotos, one of Tsipras’s chief negotiators, who became finance minister in mid-2015. ‘I think that the Greek government in the first six months tried to change the agenda – they genuinely believed that we couldn’t just ignore a popular vote that said we needed change in direction and they tried to explain that to the Europeans,’ Tsakalotos said. ‘It was worth an attempt to change. It did raise many issues. Many of the issues we raised in the first six months are now being discussed quite seriously.’

The political shift spelled the end of the fragile cooperation with the international institutions that had helped the second programme make as much progress as it did. From the perspective of the euro area authorities, Greece in the first half of 2015 turned its back on its prior agreements and lost its way out of the economic quagmire.

‘The Greek authorities decided to no longer comply with the agreement with international institutions after they won the elections in early 2015. Therefore, the Greek support programme went completely off track,’ said Dijsselbloem, former Dutch finance minister, who was Eurogroup president and chairman of the ESM Board of Governors through the latter part of the crisis.

On 4 February, just over a week after Tsipras took office, the ECB cancelled its waiver of minimum credit-rating requirements for Greek bonds that had been used as collateral for the Eurosystem’s monetary operations[2]. In plain terms, given that Greece’s sovereign credit rating was below investment grade, Greek bonds would no longer be eligible for any of the central bank’s bond-buying programmes, nor could banks use them as collateral for ECB loans. The central bank said the decision – which took effect on 11 February – was a direct result of Greece’s inability to conclude its rescue programme review.

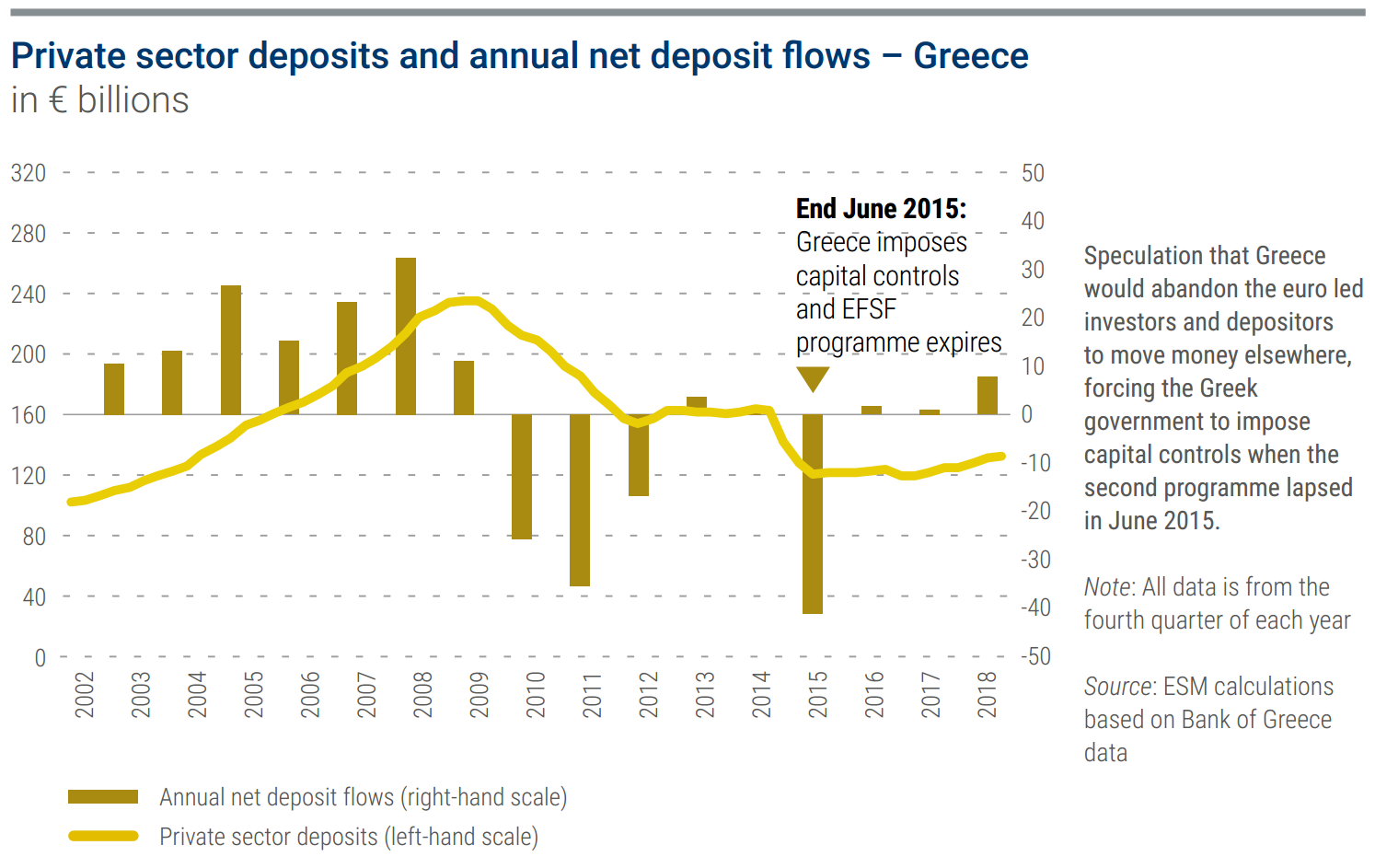

This put Greek banks in a difficult spot. Without eligible collateral, they could no longer use the ECB’s normal system of bank lending. Instead, they would have to go to the Bank of Greece to request Eurosystem emergency liquidity assistance. In the past, emergency liquidity had been a largely technical central banking operation with little or no public discussion, but now the Eurosystem’s decisions carried enormous weight and the markets reacted to the slightest fluctuations in the use of the funds. The vicious bank-sovereign circle was tightening around the Greek economy once again.

‘The developments we witnessed in the first half of 2015 were the results of deliberate political decisions, but the risk of crisis they created was also a stark reminder that there should be no complacency about the functioning of our monetary union,’ said Juncker, who was by this point the European Commission president. ‘Personally, I never believed that Greece could leave the euro, and I said so publicly.’

Personality conflicts compounded the negotiating dilemmas. As his government’s first finance minister, Tsipras picked Yanis Varoufakis, a UK-educated economist who had taught in the US and Australia. Varoufakis arrived at his inaugural Eurogroup meeting in February 2015 with a host of ideas for righting the Greek economy. Addressing fellow finance ministers for the first time, Varoufakis spoke out against budget cutting, backed an increase in the Greek minimum wage, was wary of privatisation – and asked for a bridge loan to tide Greece over the next few months.

The Syriza government’s relations with creditors were often fraught. When it took office, the euro area had already given Greece a two-month technical extension on the programme, and adding more time proved contentious. It was only after 10 further days of discussions that the Eurogroup granted a four-month extension of the second programme, rejecting Greece’s bid for six months[3].

For a brief period, Varoufakis drew as much attention as Greece’s debt, bond yields, pension cuts, or asset sales. Critics accused him of squandering an opportunity to win concessions for the newly installed government. ‘He managed to have 18 enemies. That’s all he did,’ Hardouvelis, his predecessor as finance minister, was quoted as saying in the 3 August 2015 issue of the New Yorker[4].

In response, Tsipras elevated negotiations over Greece’s fate to the highest level. It was unusual for heads of government to delve into the minutiae of the rescue negotiations, a task that had been the domain of the finance ministers and their subordinates. Tsipras’s brand of leader-to-leader diplomacy won Greece few allies, given the huge gap between what Athens was seeking and what the euro area was prepared to grant.

Euro area leaders yielded on a symbolic point, dropping the term ‘troika’ and, with an interim stop at ‘quadriga’, redesignating the international authorities as ‘the institutions’. This was an effort to defuse the Greek public’s resistance to troika oversight. ‘The Greeks were obsessing over it. I thought, what’s in a name?’ said Wieser, former chairman of the Eurogroup Working Group.

The name change also reflected the rescue management team’s expansion from the three original members to include the ESM. Once the third programme came into focus, the firewall took on a larger role in debt sustainability analysis and programme monitoring. By that point it also had built up substantial expertise on Greece – where the rescue fund had become the largest creditor – and in managing aid programmes generally.

The ESM’s mandate allowed it to focus on Greece’s finances and its risk of default, including how to define what that would look like and what sort of legal and financial consequences might result. The other institutions had taken a more general approach to monitoring macroeconomic data and Greece’s public finances. Giammarioli, who became the ESM’s Greece mission chief in January 2015, said the ESM’s viewpoint gave it additional credibility with euro area member states, since the firewall was keeping a close eye on how developments in Greece could in turn affect their finances. Increased monitoring began in the first half of 2015, as the second programme broke down, before evolving into a more formal role later in the year as the follow-on package took shape.

‘Around March to July we escalated the process, specifically for Greece,’ Giammarioli said. ‘We created an emergency situation room in case there was a default, with procedures on what legal acts would need to be signed, and so on. It was quite challenging. This was all to reassure the Members that we were prepared for any possible negative event.’

Also in early March, Greece submitted a new round of proposals to the Eurogroup, to a tepid response at best. As correspondence flew back and forth between Athens and the other capitals, financial markets were becoming more pessimistic. At the end of March, Fitch downgraded Greece to CCC from B, and a few weeks later Standard & Poor’s cut Greece to CCC+ from B, with Moody’s following suit soon afterwards[5]. During this period, Tsipras went to Moscow on 8 April 2015 for talks with Russian President Vladimir Putin[6]. The meeting didn’t yield much in the way of concrete developments, but it sent a signal that Tsipras was far from finished seeking alternatives to the euro area reform plan.

Stournaras, who was appointed Bank of Greece governor in June 2014, said Varoufakis reacted to the growing tensions within the Eurogroup by invoking ‘Plan B’ scenarios rather than shifting into a more pragmatic gear. Talk of seeking money from Russia, parallel currencies, or even taking over the Greek central bank overshadowed negotiations with the euro area, eating into public confidence and further upsetting markets.

‘He thought that he could become a hero. He played save or destroy,’ Stournaras said. ‘But a finance minister must be careful and risk-averse. He should not roll the dice as a way to determine the future of his country.’

Varoufakis thought Greece would hold a stronger negotiating hand if he could show how Grexit might be feasible. He later detailed this rationale in a book he wrote after the crisis[7].

As April drew to a close, Dijsselbloem said there was still a wide gulf between Athens and its international creditors. Dijsselbloem felt that Syriza’s election campaign had set the stage for the unproductive talks. ‘Undoubtedly the Greek government presented unrealistic promises in its election campaign, which created problems when they were in office,’ Dijsselbloem said.

Tsipras reshuffled his negotiating team in April, keeping Varoufakis as finance minister but replacing him with Deputy Foreign Minister Tsakalotos as the chief go-between in day-to-day talks with the European institutions[8]. The move also brought in George Chouliarakis to serve on the Eurogroup Working Group of finance ministry deputies, replacing a Varoufakis ally. While the new team shared Tsipras’s politics, they practised a more low-key style that smoothed discussions at the technical level. For his part, Varoufakis continued to take an active role politically.

Progress remained elusive. With more than half the extension period gone, Greece was forced in May to tap into its IMF reserves holding account to meet a €750 million repayment instalment to the Washington-based lender, an unusual use of the funds that underscored the precariousness of Greek finances[9]. Greece’s relations with the IMF suffered.

On 4 June, Greece told the IMF it would delay its next scheduled loan repayment of €300 million[10]. Meanwhile, talks with the euro area bogged down. Greece rejected creditors’ reform proposals and countered with another plan of its own. The IMF responded that there were ‘major differences’[11] between the two sides. With an agreement nowhere in sight, technical talks in Brussels broke down. In mid-June, the Eurogroup urged Greece to make new proposals, saying ‘time is really running out’[12].

In a bid to break the impasse, European Council President Donald Tusk – who had succeeded Van Rompuy in December 2014 – launched a frenetic diplomatic initiative by calling euro area leaders to Brussels for an emergency summit on 22 June 2015. Greece pulled together another set of proposals in time for the summit, reaping a cautious welcome from the leaders. It was then up to Tsipras, the institutions, and Eurogroup finance ministers to nail down an accord before the second Greek programme ran out on 30 June.

It wasn’t to be. In a week of discussions among technical experts and finance ministers, punctuated by a regularly scheduled EU summit[13], Greece mooted economic reforms and budget savings that didn’t go far enough for the creditors. Ideas were floated, but no plan for a new, comprehensive pact was formally presented. Late on Friday 26 June, the Greek negotiators walked away from the table. Early in the morning of 27 June, Tsipras announced he would hold a referendum to let the Greek people decide whether or not to accept the creditors’ latest rescue conditions[14].

That day, euro area finance ministers met, converting what had been scheduled as a final drafting session for the new programme into a discussion of an altogether different sort. There were four days left in Greece’s second rescue, even after the extension. Once it expired, Greece would lose not only its undisbursed funds, but also access to some of the other cash-boosting measures the euro area had granted, such as the sharing of central bank profits on Greek bonds held by the Eurosystem. Instead of a smooth path to a follow-on aid programme, it looked as if Greece might end up with nothing.

Greece dissented from that Saturday’s Eurogroup statement, reflecting the rupture between Athens and the rest of the currency union. ‘We stress that the expiry of the EFSF financial arrangement with Greece, without immediate prospects of a follow-up arrangement, will require measures by the Greek authorities, with the technical assistance of the institutions, to safeguard the stability of the Greek financial system’[15], the statement by the other 18 finance ministers said. They pledged to monitor conditions, stand ready to help Greece, and reconvene as needed.

On Sunday, 28 June, Greece announced it would impose capital controls and a bank holiday when markets opened on Monday[16]. The next day, on Tuesday, the second rescue programme lapsed, taking with it the prospect of any further EFSF lending[17]. Greece missed an IMF payment[18], the Eurogroup stood its ground, and Greek citizens faced an arduous week of no access to their banks and no prospect of international help.

‘Capital controls were a crisis measure,’ ESM Managing Director Regling said. ‘They should not happen in a monetary union, although it was the second time – they also happened in Cyprus in 2013. And still it was a shock. It would have been better not to get into a situation where that becomes unavoidable. But given where Greece was, there was no choice.’

The referendum went ahead on 5 July[19]. Public anger was unequivocal: Greeks voted by a margin of 61% to 39%[20] to denounce the international creditors and protest against the hardships that had befallen them since the extent of the government’s budgetary woes surfaced in 2009.

Immediately after the referendum, however, Tsipras relaunched his outreach to the creditors. He began by asking Varoufakis to resign as finance minister[21], replacing him with the more diplomatic Tsakalotos[22]. ‘In the six months of the Varoufakis tenure, about €45 billion deposits left. That says everything,’ Stournaras said. ‘This led to capital controls with the declaration of the referendum.’

On 8 July, Tsipras sought a new ESM programme. Having given voice to public grievances over the distressed state of the economy and the privations resulting from five years of spending cuts, the Greek prime minister seized the opportunity for a fresh start. A day after requesting aid, Greece submitted a new set of reform plans that would anchor a third rescue programme. It was time to turn the page.

Continue reading

[1] The Guardian (2015), ‘Alexis Tsipras sworn in as new Greek prime minister – as it happened’, 26 January 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2015/jan/26/greece-election-syriza-victory-alexis-tsipras-coalition-talks-live-updates

[2] ECB (2015), ‘Eligibility of Greek bonds used as collateral in Eurosystem monetary policy operations’, Press release, 4 February 2015. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2015/html/pr150204.en.html

[3] ‘Remarks by Jeroen Dijsselbloem at the press conference following the Eurogroup meeting of 20 February 2015’, 20 February 2015. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/02/20/eurogroup-press-remarks/

[4] New Yorker (2015), ‘The Greek warrior’, 3 August 2015. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/08/03/the-greek-warrior

[5] TradingEconomics (n.d.), ‘Greece – credit rating’. https://tradingeconomics.com/greece/rating.

[6] New York Times (2015), ‘Putin meets with Alexis Tsipras of Greece, raising eyebrows in Europe’, 8 April 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/09/world/europe/putin-russia-alexis-tsipras-greece-financial-crisis.html

[7] Varoufakis, Y. (2017), Adults in the room, Penguin, London.

[8] The Guardian (2015), ‘Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis replaced as leader of debt talks’, 27 April 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/27/greece-reshuffles-negotiating-team-creditors-yanis-varoufakis; Reuters (2015), ‘Greece moves to sideline Varoufakis after reform talks fiasco’, 27 April 2015. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eurozone-greece-varoufakis/greece-moves-to-sideline-varoufakis-after-reform-talks-fiasco-idUSKBN0NI0VI20150427?feedType=RSS&feedName=worldNews

[9] Reuters (2015), ‘Greek PM says time for action from lenders, IMF payment scrapes by’, 12 May 2015. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-eurozone-greece/greek-pm-says-time-for-action-from-lenders-imf-payment-scrapes-by-idUKKBN0NX0QW20150512

[10] The Guardian (2015), ‘Greece moves closer to Eurozone exit after delaying €300m repayment to IMF’, 4 June 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jun/04/greece-delays-300m-payment-to-imf

[11] IMF (2015), ‘Transcript of a press briefing by Gerry Rice, director, communications department, International Monetary Fund’, 11 June 2015. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/28/04/54/tr061115

[12] Press remarks by Eurogroup president following the Eurogroup meeting on 18 June 2015, 18 June 2015. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/06/18/press-remarks-eurogroup-president/

[13] The Guardian (2015), ‘Greece bailout talks break down again’, 25 June 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jun/25/greece-bailout-crisis-last-minute-search-deal

[14] Eurogroup statement on Greece, Press release, 27 June 2015. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/06/27/eurogroup-statement-greece/

[15] Ministerial statement on 27 June 2015, Press release, 27 June 2015. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/fr/press/press-releases/2015/06/27/ministerial-statement/

[16] The Guardian (2015), ‘Greek crisis: Banks shut for a week as capital controls imposed – as it happened’, 25 June 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/business/live/2015/jun/28/greek-crisis-ecb-emergency-liquidity-referendum-bailout-live

[17] ESM (2015), ‘EFSF programme for Greece expires today’, Press release, 30 June 2015. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/efsf-programme-greece-expires-today

[18] IMF (2015), ‘Statement by the IMF on Greece’, Press release, 30 June 2015. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr15310

[19] Wall Street Journal (2015), ‘Greek referendum hangs on voters’ understanding of question’, 30 June 2015. https://www.wsj.com/articles/greek-voters-to-decide-on-convoluted-bailout-question-july-5-1435691134

[20] The Guardian (2015), ‘Greek referendum: No campaign storms to victory with 61.31% of the vote – as it happened’, 6 July 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/business/live/2015/jul/05/greeces-eurozone-future-in-the-balance-as-referendum-gets-under-way--eu-euro-bailout-live

[21] Reuters (2015), ‘Greek finance minister Varoufakis resigns – statement’, 6 July 2015. https://www.reuters.com/article/eurozone-greece-varoufakis/greek-finance-minister-varoufakis-resigns-statement-idUSA8N0ZC02A20150706; Independent (2015), ‘Yanis Varoufakis resigns: His statement in full’, 6 July 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/yanis-varoufakis-resigns-live-greek-crisis-his-statement-in-full-10368320.html

[22] New York Times (2015), ‘Rift emerges as Europe gears up for new talks on Greece bailout’, 6 July 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/07/business/international/yanis-varoufakis-abruptly-resigns-as-greek-finance-minister.html