3. ‘Runaway train’: Greece sounds the alarm

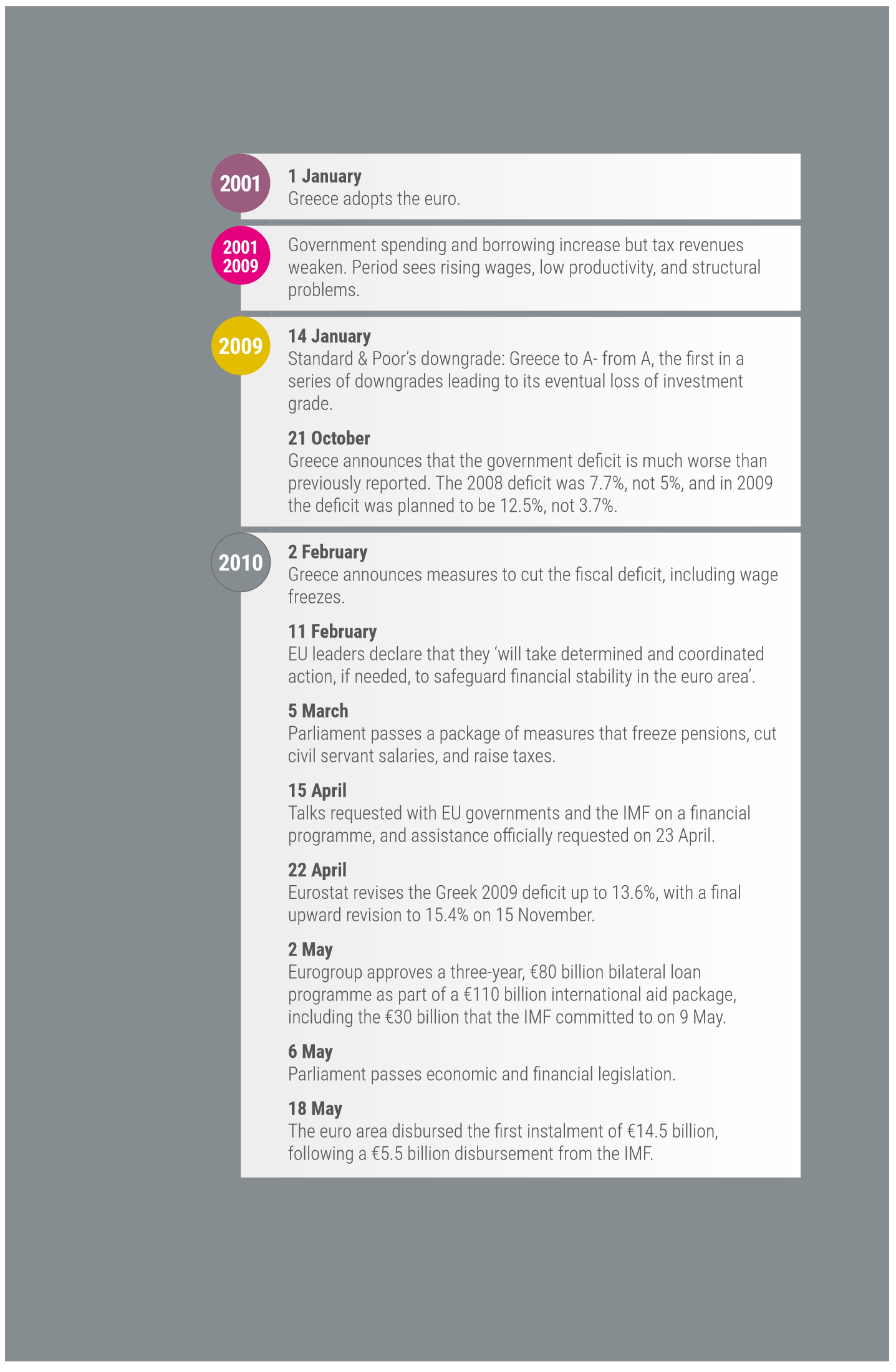

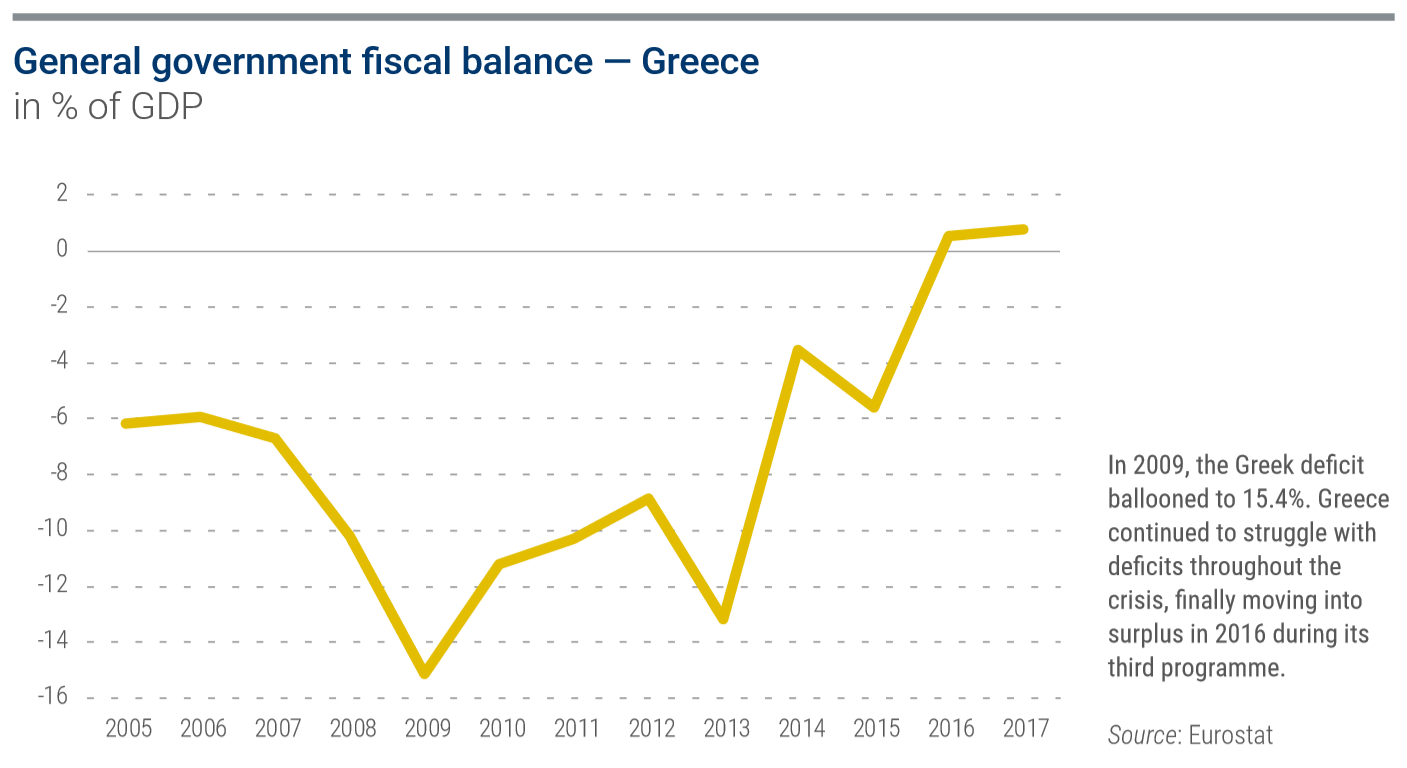

The euro’s prospects darkened in October 2009, when a newly elected Greek government led by George Papandreou announced that the country’s budget deficit was a lot higher than initially reported. When the incoming administration reviewed the figures, they saw that the country’s budgetary gap, or the shortfall between revenues and spending, was projected to be around 12.5% of gross domestic product (GDP)[1]. That contrasted with the 3.7% of GDP projection submitted by the previous government and was four times the maximum threshold of 3% set out in the euro area’s budget guidelines.

Given the exceptional circumstances surrounding the global financial turmoil, these budget targets had been relaxed, but they still offered a gauge of how far off the mark Greece had fallen.

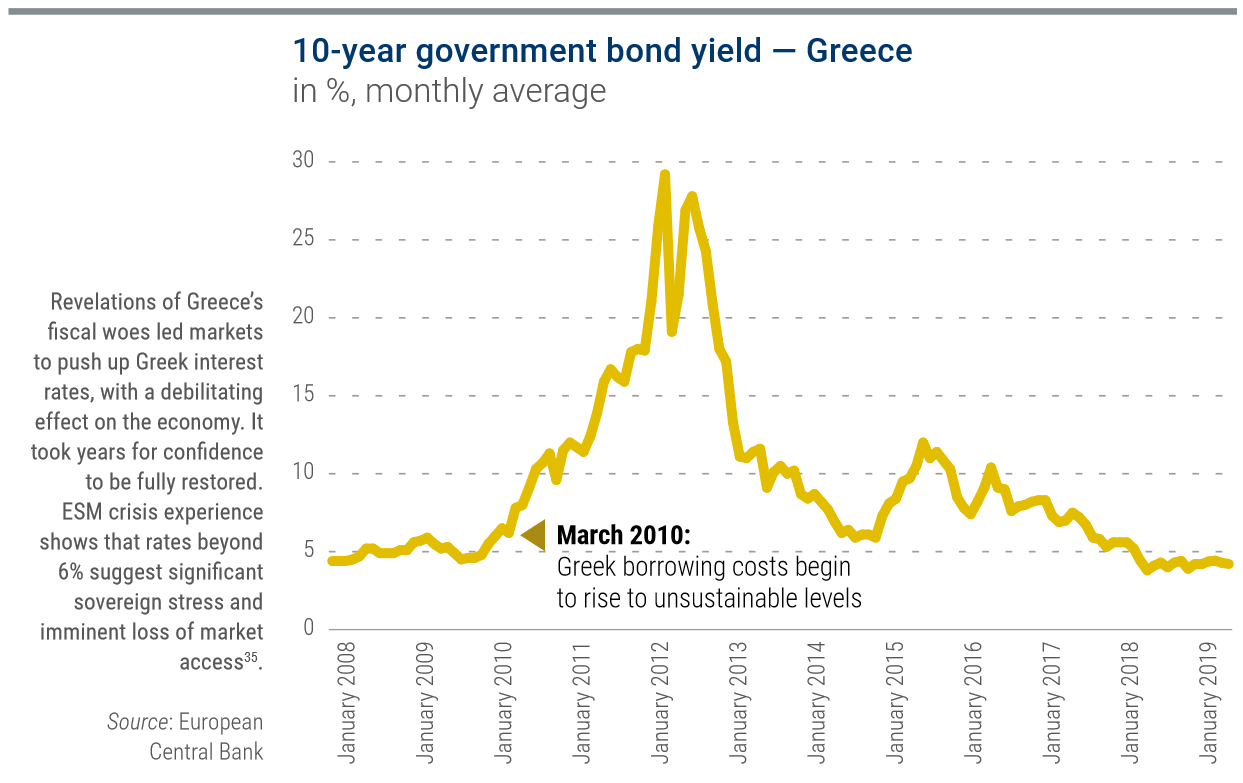

The huge fiscal deficit raised questions about the sustainability of Greece’s high and growing public debt – already in excess of a year’s GDP. Fragile markets didn’t receive the news well. Greek 10-year bond yield spreads to Germany widened to 238 basis points by the end of December from 138 basis points in early October, putting Greek borrowing costs at 5.49%, or 2.38 percentage points higher than Germany’s and suggesting growing market concern about the country’s finances.

‘From that moment on it was clear there was a big problem,’ said Maarten Verwey, at the time a senior Dutch finance ministry official, who would move to the European Commission in September 2011. ‘There were a few months during which we could see that something coordinated needed to happen for Greece. But this was very difficult politically.’

In Greece, the revised figures also came as a shock. George Papaconstantinou, the new government’s finance minister, remembers getting updated figures from his country’s central bank just days after taking office. ‘Before the election we had some idea that the numbers were wrong. But we just had no idea how wrong they were,’ he said. ‘That was the critical moment when we realised that it was a runaway train.’

Two days after the budget revisions came out, Fitch downgraded Greece’s rating for long-term debt to A- from A. Greece’s new figures showed ‘weaknesses in fiscal reporting and planning’ that cast doubt on the country’s economic path, the credit-rating agency wrote in a 22 October 2009 press release. ‘These ongoing deficiencies materially undermine the credibility of medium-term fiscal consolidation plans’[2].

On 8 December, Fitch downgraded Greece again, this time to BBB+ with a negative outlook – pushing the ratings down to two notches below where they had started the crisis. Standard & Poor’s[3] and Moody’s[4] followed suit later in the month. Investors had lost confidence in the Greek government’s ability to right its finances in the foreseeable future. As Fitch wrote: ‘Present government proposals rely more heavily on revenue-raising measures, particularly moves to counter tax evasion – where the pay-off is highly uncertain – rather than current spending where structural fiscal weaknesses are most acute’[5].

The euro fell about 6% against the dollar in December, and declined against the currencies of the EU’s major trading partners. EU leaders grew impatient with the government in Athens, and the rest of the world waited to see if Greece’s problems would spread. Geithner, who helped spearhead the US response to its worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, was one of the earliest voices calling on Europe to avert a Greek default in order to protect the euro as a whole.

In early February 2010, Greece attempted to tame its deficit with measures such as wage freezes[6]. Meanwhile, Geithner, then-German Finance Minister Schäuble, and the finance ministers of the other Group of Seven largest advanced economies met in Iqaluit, Canada, near the Arctic Circle. Geithner said he was beginning to fear that European reluctance to intervene would break the euro apart[7]. International financial markets were panicking: if one euro area member state’s statistics couldn’t be trusted then all euro members were vulnerable. The EU political consensus was that Greece was to blame for its own problems. Geithner feared that relying only on budget cuts and what he called ‘Old Testament’-style retribution could push the Greek economy over the brink. If the euro area would allow one of its own to default, financial markets might pull out of the currency bloc en masse, selling euro area government bonds or demanding punishingly high interest rates to hold on to them.

To many in the US, the EU seemed to be limiting its options. ‘The initial proposals for creating a collective funding mechanism were small, relative to the scale of the challenge,’ Geithner said. The risk of a just-big-enough safety net is that, if the market doesn’t like your plan, investors will continue selling Greek debt, he said. Then ‘you’ve accelerated the run, fuelling the fire because it looked so small’ relative to the potential size of the problem. ‘This is all about breaking the psychology of the run.’

Shortly after the Iqaluit talks, euro area leaders on 11 February 2010 held the first of a series of summits in Brussels to get to grips with Greece’s financial woes and the consequences for the wider economy. They pledged ‘determined and coordinated action, if needed, to safeguard financial stability in the euro area as a whole’, but pointed out that Greece had yet to request support[8].

In that first top-level crisis discussion, the consensus was that it was up to Greece to put things right. Euro leaders leaned on the Greek government ‘to do whatever is necessary’ to tame the deficit and ‘to implement all these measures in a rigorous and determined manner’[9].

An EU finance ministers meeting in mid-February set a deficit target for Greece of 8.7% of GDP[10] for 2010 and below 3% by 2012, in line with the stability and growth pact rules[11]. The Greek government drew up a reform package designed to meet these goals, which the EU approved. On 5 March, the Greek parliament passed a package of measures that froze pensions, cut civil servant salaries, and raised taxes[12]. The cuts caused nationwide protests, yet the EU insisted that more needed to be done. At their March meeting, the finance ministers welcomed Greece’s actions, while calling for implementation of the full slate of promised economic reforms ‘effectively, fully and in a timely manner’[13].

At a summit a week later, on 25 March, EU leaders reiterated assurances that euro area member states were planning to act together if needed. While again stressing that Greece hadn’t asked for assistance, the leaders pledged to offer a package of loans to Greece alongside an IMF programme, should it be required: ‘As part of a package involving substantial International Monetary Fund financing and a majority of European financing, euro area member states are ready to contribute to coordinated bilateral loans’[14].

European financial support wasn’t a given. Papaconstantinou said Schäuble was blunt when the two first met in Berlin in late 2009. ‘He used this phrase: “There is no Plan B, George. You have to handle it yourself.”’ France’s Finance Minister Lagarde was similarly firm at the time, while acknowledging that there might be a need to reconsider as events unfolded, he said. Subsequent trips by Papandreou to Berlin and Paris yielded similar answers.

Papaconstantinou said he and Papandreou approached Dominique Strauss-Kahn, then IMF chief, during the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in January 2010. Meeting in a kitchen so as not to attract undue attention, the trio had a frank talk about how much money might be needed and how the Washington-based lender could coordinate with EU authorities. According to Papaconstantinou, Strauss-Kahn said the IMF would help persuade the rest of Europe to find a way of helping Greece.

In March 2010, Verwey was appointed chairman of a group of national finance ministry experts tasked with looking into the complexities of the issues before the leaders’ March summit. ‘I did a first presentation about how the loan facility could be set up when I was chairman of the Task Force on Coordinated Action. This was a few weeks, about three, after we’d received the mandate from the leaders.’

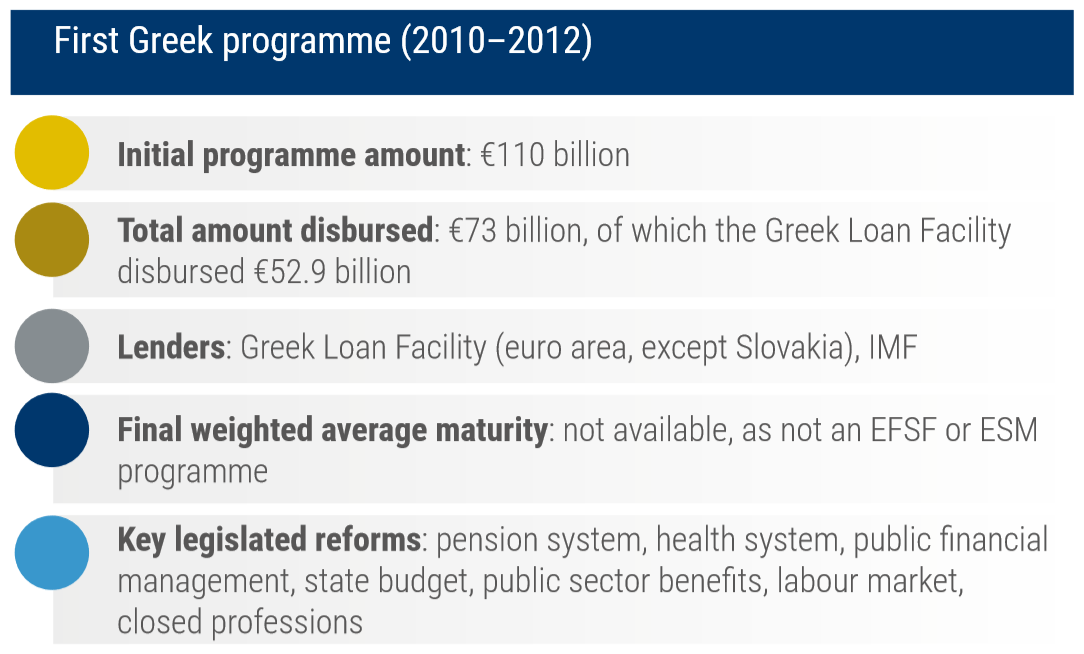

Verwey’s project was setting up what would become the Greek Loan Facility, a bundle of bilateral loans that would be pooled at the EU level and managed by the Commission. Some of the brainstorming from March and April 2010 would lead to many of the design features that ended up in the EFSF and the ESM, Verwey recalls. At the same time, there were some key differences. As a one-off arrangement encompassing 15 separate bilateral loans, the Greek Loan Facility was cumbersome and inflexible. Lending terms were also purposely less favourable than those the rescue funds introduced later.

Euro area leaders phrased it as tough-minded encouragement for Greece to get its financial act together, going out of their way to say it wouldn’t be cheap money. The 25 March statement said: ‘The objective of this mechanism will not be to provide financing at average euro area interest rates, but to set incentives to return to market financing as soon as possible by risk adequate pricing. Interest rates will be non-concessional, i.e. not contain any subsidy element’[15].

The leaders said the loan offer ‘has to be considered ultima ratio, meaning […] market financing is insufficient.’ Greece would have to be on the brink of default, with no other option but this last-resort, condition-laden lifeboat. Economic reform conditions would have to be negotiated, monitored, and agreed on before any disbursements would be possible. The March statement made it clear that the whole euro area – at that point, 16 countries – would be expected to participate.

Greece continued not asking for assistance – but the need was becoming palpable. At an 11 April meeting, euro area finance ministers hashed out a plan, while underlining that the rescue would include no subsidies. The starting point for pricing on the proposed bilateral loans would be the IMF’s formula, with adjustments from there. The terms applied rates based on the three-month Euribor rate, plus a charge of 300 basis points, with a further 100 basis points for amounts outstanding for more than three years. A further charge of 32 basis points would cover operational costs[16].

These charges eventually proved counterproductive. With a worsening situation, there was no way Greece could stabilise its finances, mend its economy, and quickly repay loans with interest rates a full three percentage points or more above the ‘normal’ market rate for stable countries. These rates would be cut several times as Greece sank into recession and fell further behind on its commitments. For its EFSF-funded second rescue and ESM-funded third rescue, the euro area would help Greece with financing at cost. But, in the beginning, the goal was to make sure any lifeline came with expensive financing terms.

On 15 April, the Greek government asked the Commission, the ECB, and the IMF to start talks about a multi-year assistance programme. The IMF’s Strauss-Kahn agreed to send a team to Athens the following week, to prepare ‘in the case that the authorities decide to ask for such assistance’[18]. On 22 April 2010, Eurostat reported a Greek 2009 deficit of 13.6%[19], and bond yields soared to an average 7.8% in April from already unsustainable borrowing levels in March. A day later, the Greek government finally applied for help[20]. The estimates for Greece’s 2009 deficit would later top 15%, with Eurostat in November 2010 putting it at 15.4% of GDP[21].

The need to act together was becoming clear, even in countries critical of Greece. The fervour of German tabloids was widely reported[22], with their stark headlines, such as: ‘The Greeks want even more of our billions!’ There were many sympathetic voices, too. In a 3 May 2010 article headlined ‘We’re buying Greek government bonds!’, the editor of the German economic daily Handelsblatt asked readers to demonstrate trust in Greece by buying Greek government bonds and said that he himself had bought €5,000 worth[23]. The Dutch business daily Financieele Dagblad on 30 April 2010 said ‘The moment has come to support Greece’[24]. But, capturing the mood in Germany, the usually reserved Die Zeit cried, ‘Greece has violated all the rules of economic rationality’[25].

After the Greek request, the aid talks moved quickly. On 2 May 2010, the Eurogroup agreed to provide bilateral loans managed collectively by the Commission in the Greek Loan Facility up to a total amount of €80 billion, to be released over the period May 2010 to June 2013[26]. Germany committed the largest share of any euro area member state, pledging to offer up to €22 billion. But, unlike other member states, which funded the Greek loans directly, Germany delegated the credit line to its state-backed development bank, KfW[27]. Alongside the euro area, the IMF put up an additional €30 billion under a stand-by arrangement.

Subsequent to the May 2010 deal, the headline amount in the Greek Loan Facility was reduced by €2.7 billion, in part because Slovakia decided later in 2010 not to participate, and in part because Ireland and Portugal stepped out once they requested financial assistance themselves[28]. Overall, the difficult shared effort to make individual loans to Greece underlined the need for an alternative approach.

‘In principle, it would have been preferable to calculate the fiscal needs on the basis of a debt sustainability analysis. But, in practice, the spending limit of the Greek Loan Facility created a ceiling that could be used for the fiscal rescue of Greece,’ said Rehn, who was then the European commissioner for economic and monetary affairs and the euro. He credits Strauss-Kahn with making efforts to ensure the IMF’s contribution was as high as it was.

Even though the initial design was far from ideal, the euro area and its allies had come together to protect the currency union. ‘The idea behind the Greek Loan Facility was: we’ll do something for Greece now quickly,’ Verwey said. ‘Because people feared there would be contagion if we didn’t take action. They were especially afraid of contagion through the financial channel, through bank exposures to Greece – in countries other than Greece – so something needed to happen.’

The worries were justified. EU banks held around €95 billion in Greek government bonds, according to a May 2011 report by Moody’s[29], which noted ‘above-average’ exposures in Belgium, Germany, France, Cyprus, and Luxembourg. At the time, however, the prevailing wisdom in Germany and elsewhere was that Greek profligacy was to blame for the crisis.

To access the Greek Loan Facility funds, Greece agreed to a new wave of fiscal consolidation, on top of the cuts that were already underway, to prune its deficit to 2.6% by 2014[30]. There were revenue-raising measures worth about 4% of GDP over the programme period, mostly by increasing the value added tax, for example on luxury items, tobacco, and alcohol[31]. The programme aimed to modernise public administration, sell off state-owned enterprises, and slash defence spending while building a rational social safety net. It also set aside funds to shore up the banks and set up a structure to deal with financial stability.

Wage and pension cuts were at the heart of the efforts. The programme called for reductions in government entitlement and retirement programmes across society. ‘Selected social security benefits will be cut while maintaining benefits for the most vulnerable,’ the IMF said. ‘Comprehensive pension reform is proposed, including by curtailing provisions for early retirement’[32]. The public sector was further targeted. Its administrative apparatus ‘was way less advanced than many would have thought,’ for example lacking a common registry for state employees so it was impossible to know how many there were, according to the euro area rescue fund’s Chief Economist Rolf Strauch.

The plan called on Greece to reduce and freeze pensions and wages for government workers, and it abolished the workers’ Christmas, Easter, and summer bonuses. The freezes would be in effect for three years, and the total effort included a wide range of measures. For example, it was designed to slash 5.25% of GDP in government spending through 2013, while raising 4% of GDP through various revenue measures. There were protections for the lowest-paid workers, and Greece was also supposed to strengthen its tax collection and budget controls to gradually recoup savings of 1.8% of GDP through structural reforms[33]. ‘A significant real devaluation – in other words a cut in real income – was unavoidable not only to reduce the fiscal deficit but also to improve competitiveness quickly,’ Regling said.

The scope of the plan reflected the limits of what the euro area was able to offer Greece at the time, coupled with optimistic expectations about what Greece would be able to accomplish. This would eventually require the euro area to create its own aid fund, rather than stick with the loan facilities set up in Greece’s first rescue.

‘Perhaps we were too naïve about the Greek authorities’ willingness and ability to implement the structural reforms that were called for in that first programme,’ said John Lipsky, then the IMF’s first deputy managing director. ‘Long story short, very few of the agreed structural actions were implemented, and in total, the few that were undertaken were largely ineffective.’

The continued market volatility made it ‘obvious that some kind of funding mechanism was needed,’ Lipsky said. ‘It was only at the last minute, in the face of impending disaster, that agreement on the EFSF was reached.’

Its own budget efforts notwithstanding, Greece became increasingly unable to quieten market fears on its own, Papaconstantinou recalled. ‘The markets were not just looking for a fiscal consolidation attempt,’ he said. ‘The markets were looking for a backstop. They were looking for a guarantee of no default. And that was beyond us. This was not something we could do. This had to do with the collective response from the rest of the Union.’

In the week after the euro area signed off on the first Greek programme, the package made its way through national approval procedures and became ready to deploy. But there was no time to celebrate. ‘Eventually, the Greek Loan Facility was approved by the parliaments,’ Verwey said.

‘The last approval was received on 7 May, a Friday. But on that same day, the contagion was already there,’ he said. ‘By then it was clear we needed heavier ammunition.’

Continue reading

[1] European Commission (2010), ‘Report on Greek government deficit and debt statistics’, COM(2010), 8 January 2010, p. 3. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/4187653/6404656/COM_2010_report_greek/c8523cfa-d3c1-4954-8ea1-64bb11e59b3a

[2] FitchRatings (2009), ‘Fitch downgrades Greece to “A-” from “A”; Outlook negative’, Press release, 22 October 2009. https://www.fitchratings.com/site/pr/521696

[3] TradingEconomics (n.d.), ‘Greece – credit rating’. https://tradingeconomics.com/greece/rating

[4] Moody’s (2009), ‘Moody’s downgrades Greece to “A2” from “A1”’, Rating action, 22 December 2009. https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-downgrades-Greece-to-A2-from-A1--PR_192460

[5] FitchRatings (2009), ‘Fitch downgrades Greece to “BBB+”; Outlook negative’, 8 December 2009. https://www.fitchratings.com/site/pr/544018

[6] European Commission (2010), ‘Commission assesses stability programme of Greece; makes recommendations to correct the excessive budget deficit, improve competitiveness through structural reforms and provide reliable statistics’, Press release, 3 February 2010. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-10-116_en.htm

[7] Geithner, T.F. (2014), Stress test: Reflections on the financial crisis, Random House Business, New York.

[8] Statement by the Heads of State or Government of the European Union, 11 February 2010. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/20485/112856.pdf

[9] Ibid.

[10] Greece, Ministry of Finance (2010), ‘Update of the Hellenic stability and growth programme, including an updated reform programme’, Athens, 15 January 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/economic_governance/sgp/pdf/20_scps/2009-10/01_programme/el_2010-01-15_sp_en.pdf

[11] European Commission (2010), ‘Memo on the Eurogroup and ECOFIN ministers meetings of 15 and 16 February 2010’. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/articles/eu_economic_situation/2010-02-16-eurogroup_ecofin_en.htm

[12] European Commission (2010), ‘Communication from the Commission to the Council: Follow-up to the Council Decision of 16 February 2010, giving notice to Greece to take measures for the deficit reduction judged necessary in order to remedy the situation of excessive debt’, 9 March 2010. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52010DC0091

[13] Economic and Financial Affairs (2010), ‘Main results of the Council’, 16 March 2010, Press release. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofi…

[14] Statement by the Heads of State or Government of the euro area, 25 March 2010. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/21429/20100325-statement-of-the-heads-of-state-or-government-of-the-euro-area-en.pdf

[15] Ibid.

[16] Statement on the support to Greece by euro area Members [sic] States, 11 April 2010. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/113686.pdf

[17] ESM (2018), ESM annual report 2017, p. 41, 21 June 2018, Publications Office of the European Union (Publications Office), Luxembourg. https://www.esm.europa.eu/publications/esm-annual-report-2017

[18] IMF (2010), ‘IMF statement on Greece’, Press release, No. 10/152, 15 April 2010. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr10152

[19] Eurostat (2010), ‘Provision of deficit and debt data for 2009 – first notification’, Press release, 22 April 2010, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/5046142/2-22042010-BP-EN.PDF/0ff48307-d545-4fd6-8281-a621cbda385d

[20] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2010), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece’, European Economy Occasional Papers 61, May 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2010/pdf/ocp61_en.pdf

[21] Eurostat (2010), ‘Provision of deficit and debt data for 2009 – second notification’, Press release, 15 November 2010. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/5051930/2-15112010-AP-EN.PDF/6704b50f-d771-4c98-889e-261a5f74396d

[22] Handelsblatt (2010), ‘Wir kaufen griechische Staatsanleihen!’ (‘We’re buying Greek government bonds!’ (ESM translation)), 3 May 2010. http://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/deutschland/handelsblatt-aktion-wir-kaufen-griechische-staatsanleihen/3426508.html

[23] The Guardian (2010), ‘EU debt crisis: German papers whip up anti-Greece fury’, 29 April 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/apr/29/eu-debt-crisis-german-papers-whip-up-anti-greek-fury

[24] Financieele Dagblad (2010), ‘Zware kritiek op Duitse regering’ (‘Serious Criticism of German government’ (ESM translation)), 30 April 2010. https://fd.nl/frontpage/Print/krant/Pagina/Economie___Politiek/700583/zware-kritiek-op-duitse-regering

[25] Die Zeit (2010), ‘Genug, Athen!‘ (‘Enough, Athens!’ (ESM translation)), 4 February 2010. https://www.zeit.de/2010/06/Kommentar-Griechenland

[26] Statement by the Eurogroup, 2 May 2010. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/25673/20100502-eurogroup_statement_greece.pdf

[27] KfW (2010), ‘Involvement of KfW Bankengruppe in financial support measures for Greece’, 20 May 2010. https://www.kfw.de/KfW-Konzern/Investor-Relations/Die-KfW-als-Emittentin/Publikationen/Newsletter-Kapitalmarkt/Update-2010/20.05.2010/index.html

[28] European Commission (n.d.), ‘Financial assistance to Greece’. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/eu-financial-assistance/which-eu-countries-have-received-assistance/financial-assistance-greece_en

[29] Moody’s Investors Service (2011), ‘Weekly credit outlook’, 16 May 2011, p. 14. https://www.moodys.com/researchdocumentcontentpage.aspx?docid=PBC_133114

[30] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2010), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece’, European Economy Occasional Papers 61, p. 12, May 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2010/pdf/ocp61_en.pdf

[31] Ibid., p. 14.

[32] IMF (2010), ‘IMF survey: Europe and IMF agree €110 billion financing plan with Greece’, 2 May 2010. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/28/04/53/socar050210a

[33] Ibid.