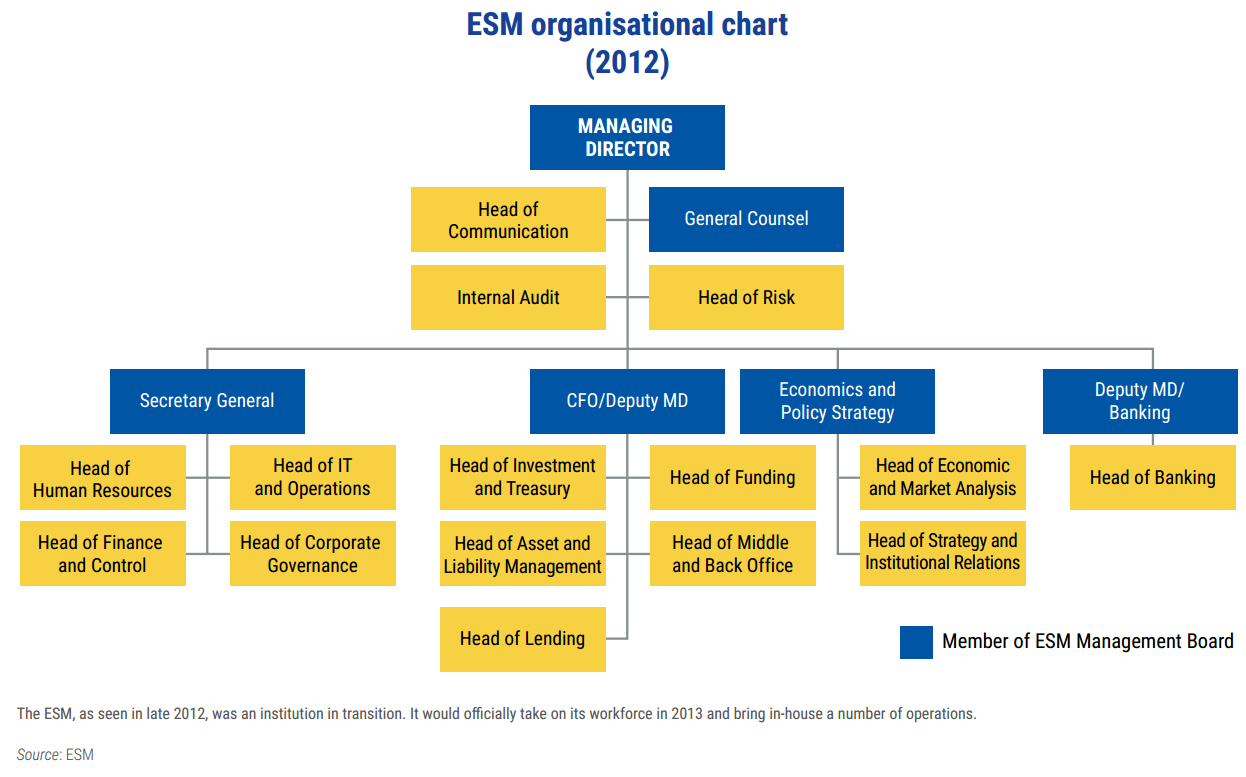

As the temporary fund prepared in 2012 to evolve into its permanent form, the ESM faced the same challenges as a start-up in the private sector: how to retain the nimble, entrepreneurial spirit of the early days while providing structure, and a career path and positive working environment for the professional staff.

Regling, chief executive of the EFSF, shepherded the permanent firewall into being. Throughout this transition, Regling sought to maintain the cultural middle ground between a freewheeling entrepreneurial spirit and a rules-bound public institution, according to EFSF Secretary General Anev Janse.

‘Klaus said, “I know what I don’t want. I don’t want to recreate existing financial institutions. I want something new, something fresh,”’ Anev Janse recalled. ‘He also felt the idea of creating a “modern international financial institution” was a bit intangible.’

A permanent institution brought the need for a longer planning horizon and a host of questions about recruitment, employee retention, workforce development, and office culture. As with the EFSF, the timeline for setting up the full-scale ESM was short. Initial plans in November 2011 envisaged an 18-month launch phase.

Under the exigencies of the crisis, however, the official start date had been brought forward to mid-2012, shrinking the preparation time. In December, at the same time as the firewall made its first disbursement to Spain, it moved into its permanent headquarters. Then, in January 2013, it acquired a workforce, taking over all the previous employees of the EFSF as well as integrating those seconded from other institutions and recruited from the private sector.

Chief Economist Strauch, who was loaned from the ECB at the EFSF’s inception, said the move to the ESM involved a big shift from the minimalist mindset at the firewall’s start. The euro backstop was supposed to be a temporary mechanism that would not be used and would later be disbanded. But the currency area’s needs required a change of plans. ‘My original idea was that I would come for one year,’ Strauch said. ‘Now I have a permanent contract. And we have loans to Greece until 2060 or beyond.’

As head of human resources and organisation, the EFSF brought in Sofie De Beule-Roloff, a Belgian with a background in the airline industry who had been helping companies establish in Luxembourg. When she joined in June 2012, there was no human resources division and staffers worked under an array of different contracts. Because the EFSF had been created on the fly, the basic infrastructure that is common even in small firms was patchy. This needed to change as the ESM came into being.

‘Well, the daunting challenge was there was no HR department,’ De Beule-Roloff said. ‘When I joined I was employee number 23 and I had a target to reach 75 staff members by the end of that year. But before we could do that, I had to create a structure to accommodate us all. It was like building a house from the ground up.’ That included developing a health insurance, pension, and social security scheme. The EFSF had been established as a company under Luxembourg law and was part of the national system. But as an international institution, the ESM would have to set up its own structures.

‘Suddenly you don’t have health care anymore, you have no retirement scheme, you have no compensation or benefit schemes, no employment rules,’ De Beule-Roloff said. ‘Because we were no longer directly bound by any national legislation, we needed to set up our own internal rules and practices.’

A first task was to rethink what to outsource – for example back office functions such as payroll and contract preparation – and determine which areas required in-house expertise. Once those skill sets were identified, the ESM strove to recruit a pool of talented people whose careers might grow alongside the institution.

As an international organisation, the ESM is unlike EU institutions in that it does not require new hires to have EU citizenship. To ensure it could attract top staff, the ESM decided to set no national hiring quotas. The only stipulation is fluency in English, the international language of finance, which has been the working language since day one of the EFSF. While staff converse in their native languages as part of the daily ebb and flow, the English-only principle has been especially important for all written documentation, ensuring nothing gets lost in translation. The worldwide talent pool brings other benefits too, from understanding European economic developments in a global context to smoothing funding operations outside Europe.

For the early staffers, the demands of the job added up to sleepless nights, last-minute train trips and flights, and weekends away from family and friends – with agendas and policy planning routinely upended by the latest economic statistic, move in the bond market, or political utterance. It was a journey into the unknown, with all the attendant exhilaration and stress.

Blondeel, who became the rescue fund’s chief corporate officer, said it took a while to strike the right work/life balance, especially when the fund was in its infancy. On her own in Luxembourg before her husband relocated, Blondeel said the start-up days were marked by wall-to-wall work.

With experience in setting up a French public agency and in modernising the administration of the debt office, Blondeel called it a ‘natural move’ to lend her expertise to the fledgling rescue fund. ‘I very much enjoyed the freedom, positive stress, and pioneering spirit that united all the EFSF early joiners,’ she said. ‘It was a strange life, because my family was still in France. But, as is the case for many people, I would work hard during the week and come back home during the weekend to see my family.’

Attracting the high calibre of staff needed hasn’t always been easy. As the second smallest country in the EU, Luxembourg doesn’t have the supply of workers, or jobs, of its larger neighbours. Much of the Grand Duchy’s workforce commutes in from neighbouring Belgium, Germany, or France, but, for those recruited from further afield, relocation often poses a problem for families. In addition, while English is the lingua franca of the ESM, German and French are more commonly heard in other workplaces – limiting the options for trailing spouses who don’t speak those languages. To smooth things for dual-career couples, the ESM offers German, English, French, and Luxembourgish language courses and helps to find jobs for partners.

‘We do a lot to integrate staff members’ families, because Luxembourg is not an easy place for partners to find suitable jobs,’ De Beule-Roloff said. ‘We are trying to help families integrate here over time so they can stay. Luxembourg is not an obvious choice for many people.’

From the start, the ESM has sought to include a mix of personal and professional backgrounds. Staff come from the public and private sectors, and there has been a bid for diversity in terms of age, sex, and national origin. About 25% of the staff are hired locally, although they may not necessarily be citizens of Luxembourg. By 2018, the ESM had staff members who hailed from 42 countries and spoke 33 languages. Some 60% had joined the institution from the private sector, and 40% from public institutions.

‘We do not recruit people who are routine job seekers,’ De Beule-Roloff said. ‘You need people with a can-do attitude and you need people to trust each other, who are willing to make decisions even when they don’t hold all the cards.’

Staff retention has become crucial as the ESM puts down institutional roots. What is particularly important, De Beule-Roloff said, is to maintain the institutional memory by retaining experienced people who could leave large knowledge gaps in their absence. The ESM also promotes mobility within the organisation. In keeping with its all-hands-on-deck mentality and because of its evolving mission, internal job changes are not unusual. For example, if someone from a middle office function wanted to take a funding role, then move from funding to investment, the organisation would support the move – provided the applicant had the right credentials.

This philosophy infuses the senior management team. In 2016, with the work of crafting new tools and programmes mostly complete for the time being, the ESM rejigged some management duties. CFO Frankel swapped some responsibilities with Anev Janse, and the Board separated its investment and funding lines of reporting. Part of the logic was to retain these expert staff who had been with the institution for the past six years, but keep their jobs interesting with a new focus.

As the institution hired, senior management took the time to reflect on how to build a corporate culture conducive to accentuating the upside of working on behalf of the European public while cushioning the inevitable stresses.

The fund turned to Deborah Henderson of Centre for Inspired Leadership, a Canadian-born consultant based in London, to help to hone a corporate culture that would bring out the best in all, taking into account the challenges of its systemic, political, and economic environment. Henderson recognised early on that the rescue fund – owned by euro area governments, responsible to them and the public, and inextricably connected with banking and the financial markets – would need to work relentlessly at developing and maintaining its diverse culture within such a context.

The ESM ‘has so many unique features to it that are different from most organisations, even for civil service organisations, by virtue of its origins, its structure, and its stakeholders, and because it’s in the centre – a perceived safe haven – in any euro financial storm,’ Henderson said.‘It is an organisation that will constantly need huge investment in its culture and in its leadership to navigate the complexities and uncertainties of its environment and maintain its overall sense of purpose.’

Henderson first surveyed the EFSF’s then-25 employees. She drew on a popular business assessment tool to tap into employees’ perceived values, aspirations, needs, and attitudes and to identify obstacles to better performance and increased job satisfaction.

The tool was designed around the premise that employees often know better than their higher-ups how to achieve their maximum potential. The online survey asked three questions: about the employee’s primary personal values, the values he or she perceived at the EFSF, and the values needed to enhance the organisation’s performance.

Employees felt that the rescue fund should be sure to cultivate a culture of teamwork, openness, and employee recognition, as well as continuous improvement, while focusing on the shared vision. Many of the 21 employees who filled in the survey saw the EFSF as a unique opportunity to help Europe through troubled times.

However, there were cautionary signs as well. Staff saw only one value – commitment – embedded in the organisation as it was then constituted. Long hours in the office or on the road were viewed as the rescue fund’s biggest drawback, pointing to the gruelling workload as a possible source of burnout. Given the crisis conditions of the start-up, it was understandable that some fear-driven values also showed up – such as confusion and internal competition.

It was an opportune time to assess the mood within the organisation, and the EFSF responded by instituting seven values that now embody the rescue fund’s core culture: health and well-being, respect, excellence, teamwork, creativity, making a difference, and ease with uncertainty[1]. These fundamental tenets are flanked by a commitment to diversity.

The senior management endorsed the conclusions from the online survey and follow-up dialogue sessions. Importantly, the resulting cultural commitments evolved from within the organisation instead of being imposed from above. Regling praised Henderson’s approach to shaping the internal discussions. ‘She said if you don’t work on building your own culture by design, you will still have a culture by default – but not usually the one you want,’ Regling said.

Although the euro economy is enjoying relatively favourable economic conditions today, in part due to the work of the EFSF and ESM, everyone who works at the firewall is keenly aware of what was so recently at risk. The ESM’s Giammarioli grew up in Italy with an Italian father and Finnish mother, at a time before Finland joined the EU. Europe’s past was etched into his family’s history. ‘My two families, 3,000 kilometres apart, suffered greatly during World War II,’ Giammarioli said. ‘Europe has guaranteed the last 75 years of peace, prosperity, and growth. In the crisis, that came under threat. I see myself as a small actor in this big picture, trying to help principles that were developed decades ago move forward.’

Continue reading

[1] ESM (2018), ‘Working at ESM’, December 2018. https://www.esm.europa.eu/careers/working-esm