From savings to spending: Fast track to recovery

Household savings increased to unprecedented levels during the pandemic as extraordinary levels of uncertainty were accompanied by pandemic-induced restrictions on households’ opportunities to spend. In this blog post, we quantify the drivers for the exceptional rise in household savings and analyse how the use of these extra savings will determine the speed of economic recovery. If vaccine progress continues and policies remain in place to encourage a speedier spending of the extra savings, we could regain pre-pandemic gross domestic product (GDP) growth levels sooner than currently forecasted.

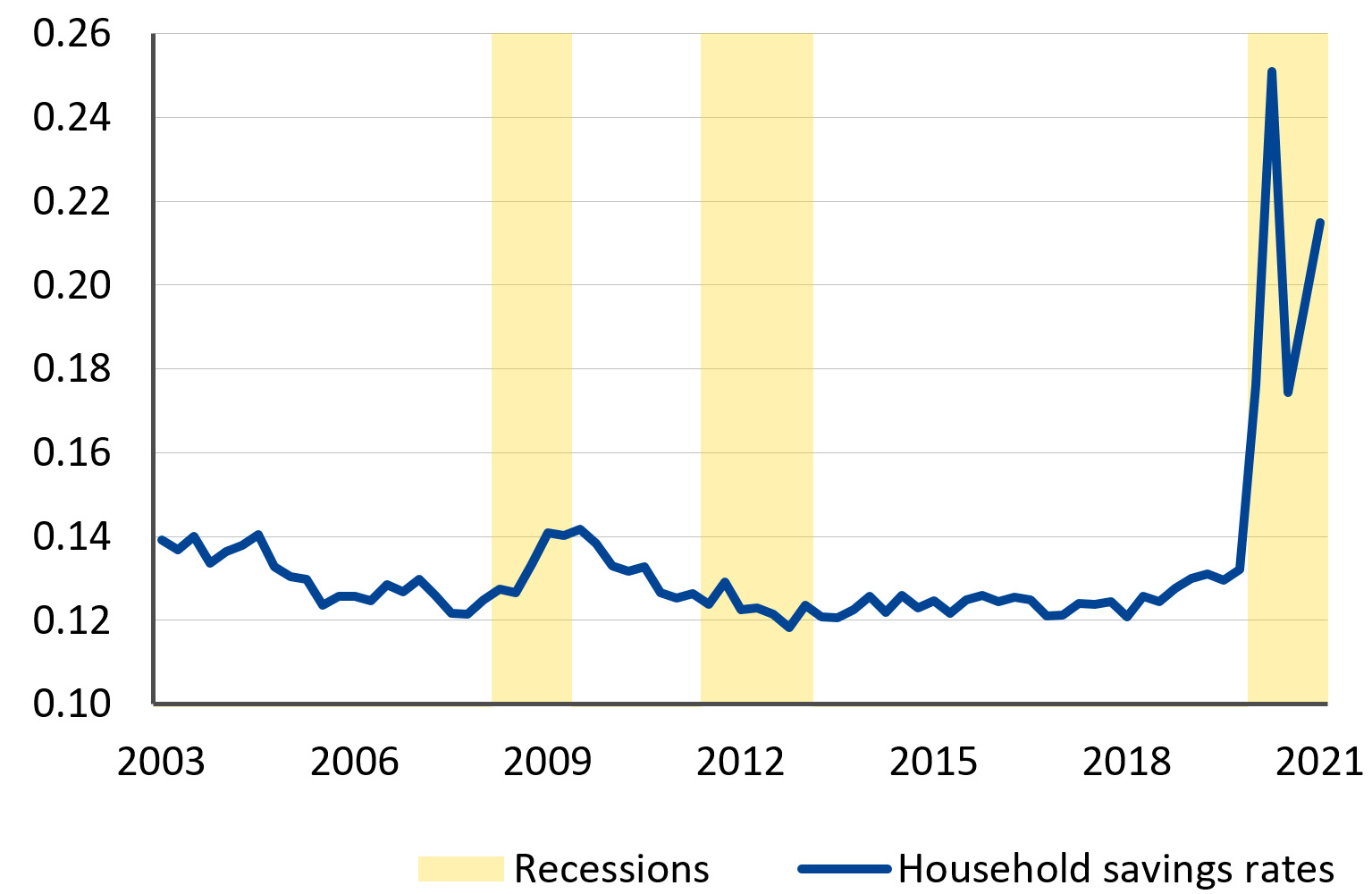

During the coronavirus pandemic, euro area household savings – income not used for consumption – rose to unprecedented levels, as was the case in many industrial countries. In 2020, the annual savings ratio in the euro area, household savings[1] as a fraction of their disposable income, increased by around 7 percentage points (pp) to about 20% of disposable income. This corresponds to about €1,400 billion in savings, or the equivalent of around 12% of 2019 euro area GDP. When the pandemic hit in the second quarter of 2020, savings increased by more than 90% compared to the fourth quarter of 2019. While the savings rate decreased in summer when lockdowns eased, it increased again to 21.5% in early 2021, as a result of the second wave of lockdowns in winter (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Euro area household savings rates

(in terms of gross disposable income)

Source: ESM calculations based on Eurostat and CEPR Euro Area Business Cycle Dating Committee (for recession periods)

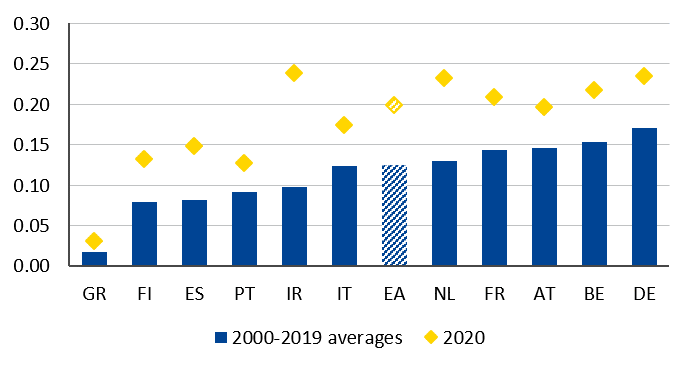

Such swings are unusual. Before the pandemic, household savings fluctuated only moderately around the historical average of 13% of disposable income. During the financial crisis, the savings rate increased only slightly by 2pp. Regarding the savings level, there is some heterogeneity across euro area countries. Greek households tend to save the least at 2% of disposable income, on average, while Germans save 17%, the most in the euro area (see Figure 2). However, during the pandemic savings ratios increased in all euro countries to historical highs.

Figure 2: Household savings rates: euro area country comparison

(in terms of gross disposable income)

Source: ESM calculations based on Eurostat

Note: Savings rates are computed as gross savings (ESA 2010 code: B8G) divided by gross disposable income (B6G). The latter is adjusted for the change in the net equity of households in pension fund reserves (D8net), except for Ireland (for the third quarter and fourth quarter of 2020) and Greece. Annual saving rates are computed as quarterly averages.

Drivers of the unprecedented increase in household savings

Spending and saving are two sides of the same coin and ultimately depend on households’ confidence in the future. Income prospects mainly determine the amount of savings in normal times. A higher income normally leads to higher savings. In periods of lower income, such as during a crisis, households use their savings to maintain their consumption level. However, if future income is uncertain because of a higher unemployment risk, people consume less and save more for precautionary motives.

The pandemic has been unusual as extraordinary levels of uncertainty have accompanied exceptional restrictions on households’ opportunities to spend. Uncertainty about how the pandemic will evolve and its effect on individuals has resulted in a historically high level of savings for precautionary motives. Lockdowns limited consumption as restrictions have prevented people from shopping, eating out, and travelling, and “forced” people to save more while extensive policy measures forestalled a precipitous fall in household income.

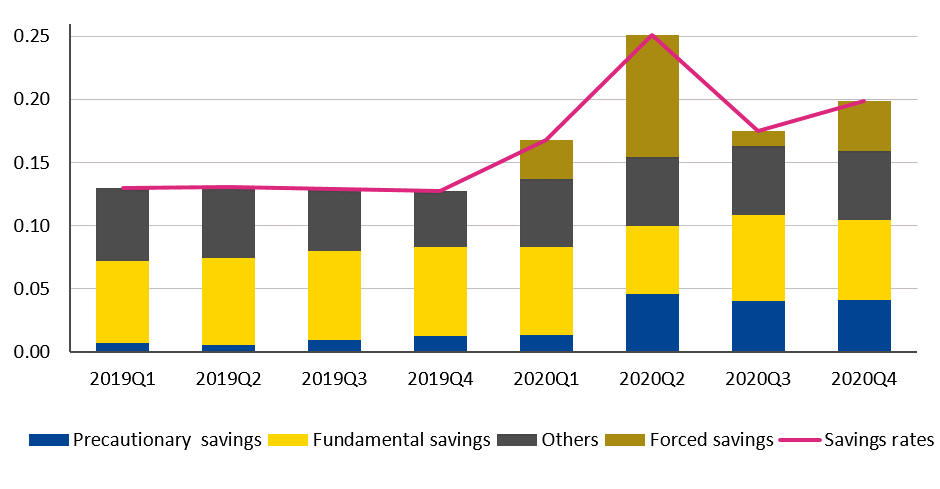

Therefore, as shown in Figure 3, the main reasons for the unusually high level of savings are:[2]

- the elevated level of precautionary savings, due to uncertainties about the future, and

- forced savings, due to missed consumption opportunities.

Since households saved more than under normal circumstances, they accumulated “unplanned” wealth during the crisis.

According to our estimates, the stock of excess savings in 2020 amounted to around €600 billion, equivalent to 5% of 2019 GDP or 8% of households’ disposable income. Around 45% of this amount were forced savings and the remaining part were precautionary.

Figure 3: Euro area household savings rates decomposition

(in terms of gross disposable income)

Source: ESM calculations based on Eurostat

Note: The figure shows the result of a panel regression model used to assess the determinants of saving ratios in the euro area to the fourth quarter of 2020 from the first quarter of 2019. The blue bars represent precautionary savings, captured by the impact of households’ unemployment expectations one year ahead, as a proxy for the unemployment risk perceived by households. The yellow bars show fundamental savings, proxied by the impact of expected financial situations, credit conditions, and the lagged household net worth. The grey bars include the residuals and the constant of the regression model and the brown bars show the forced savings that resulted from limited consumption opportunities.

Saving and spending patterns will shape the recovery

Looking ahead, the pace of the recovery will depend heavily on what households do with their additional accumulated wealth and how fast they normalise their savings behaviour. Once containment measures disappear and uncertainty dissipates, savings might return to normal levels and unleash pent-up demand, thereby boosting the recovery thanks to higher levels of consumption. The key question is when exactly this will happen. The faster savings levels decline, the faster the economy will rebound. At present, it is unclear how consumers will behave – even if the European Central Bank’s (ECB) monetary policy stance remains unchanged, as assumed in the following.

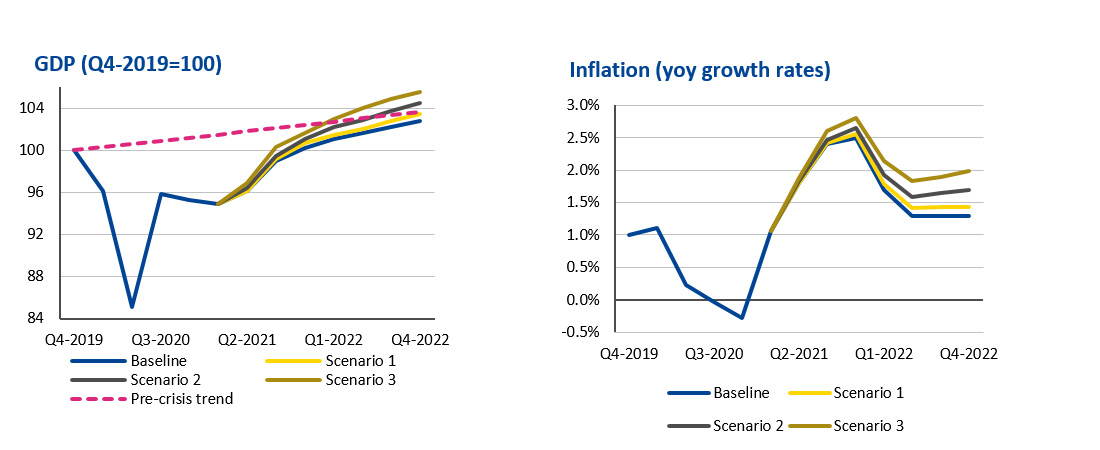

The European Commission estimates that GDP growth in the euro area will catch up with the pre-crisis trend in late 2022. This is based on the assumption that excess savings will be reduced over the projection horizon. Building around such a baseline, we have calculated alternative scenarios based on different spending patterns as shown in Figure 4. The scenarios show how it is possible to regain pre-pandemic GDP levels sooner if households spend more of their excess savings faster.

- Scenario 1. Households might decide to leave the stock of excess savings untouched because governments could increase taxes after the pandemic. In such a scenario, GDP growth could reach 5.0% this year and 4.8% next year. The savings ratio will return its pre-pandemic average by the end of 2022. GDP will be 0.2pp higher in 2021 and 0.3pp higher in 2022 than without the stimulating effects through pent-up demand. Inflation will reach the ECB’s 2% target in 2021 and fall below it in 2022 (1.5%).

- Scenario 2. Once the pandemic is brought under control, households could use the additional wealth and spend a small part of their accumulated excess savings. The extra-accumulated wealth is reduced by 10% in 2022. Savings ratios fall slightly below the historical average to about 12% in 2021. In this scenario, GDP could grow up to 5.2% in 2021 and 5.5% in 2022, reaching its pre-crisis trend early next year. This would bring inflation 0.2pp higher in 2022.[3]

- Scenario 3. Consumers might decide to make even more expenditures – at least temporarily – that they had put off once the pandemic has been resolved globally. A 30% reduction of the accumulated wealth in 2022 implies a fall in the savings ratio to about 10%, reflecting a historical low. In this scenario, GDP growth could increase to 5.7% in 2021 and to 6.0% in 2022. GDP could reach its pre-crisis trend already at the end of 2021 and exceed it thereafter. Inflation would be at or slightly above 2.0% this and next year.

Figure 4: Economic impact of reduction in household savings

Source: ESM calculations based on European Commission

Note: The blue line is the baseline that assumes a gradual reduction of excess savings over the forecast horizon. The savings ratio is still above pre-pandemic level at the end of 2022. The pre-pandemic trend extrapolates pre-crisis forecasts. Scenario 1 assumes a reduction of excess savings to zero by the end of 2022. Scenario 2 assumes an unwinding of the additional stock of excess savings in 2022 by 10%. Scenario 3 assumes a reduction of excess savings to zero at the end of 2021 and an unwinding of the additional stock of excess savings in 2022 by 30%.

As we can see in the different scenarios, unlocking the excess savings to increase consumption can accelerate the return of GDP to pre-crisis trends. As seen in the right panel of Figure 4, a faster spending of savings will also increase inflation.

These scenarios can be a useful tool for policymakers to gauge the impact of pent-up demand on the recovery.

Saving levels will only remain persistently high if consumption opportunities are permanently lost and households permanently consume less, but this is unlikely.

In the medium to long term, an efficient implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Plans under the Next Generation EU programme might increase long-term growth perspectives, stabilise employment expectations, and thereby trigger a faster and more substantial release of pent-up demand.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Niels Bünemann, Pilar Castrillo, Sharman Esarey, Niels Hansen, Gergely Hudecz, George Matlock, Brenda Nolden, and Rolf Strauch for valuable comments and contributions to this blog post.

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager