Navigating quantitative tightening: funding Europe’s future without rekindling the sovereign-bank nexus

Europe faces substantial investment needs to tackle structural changes and to future-proof its economy, which will lead to rising levels of public debt. This burden comes at a time when the Eurosystem, the major buyer of sovereign debt over the past decade, has stopped net asset purchases and reinvestments. This brings the question: who will absorb the additional debt? In the past, banks played a major role, but the destructive force of the sovereign-bank nexus Europe acutely felt during the sovereign debt crisis exposed the financial stability risks of relying excessively on them. Following the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) mandate, we explore how a diverse investor base can help meet these financing needs without rekindling the sovereign-bank nexus.

Europe faces a defining moment amid mounting pressures

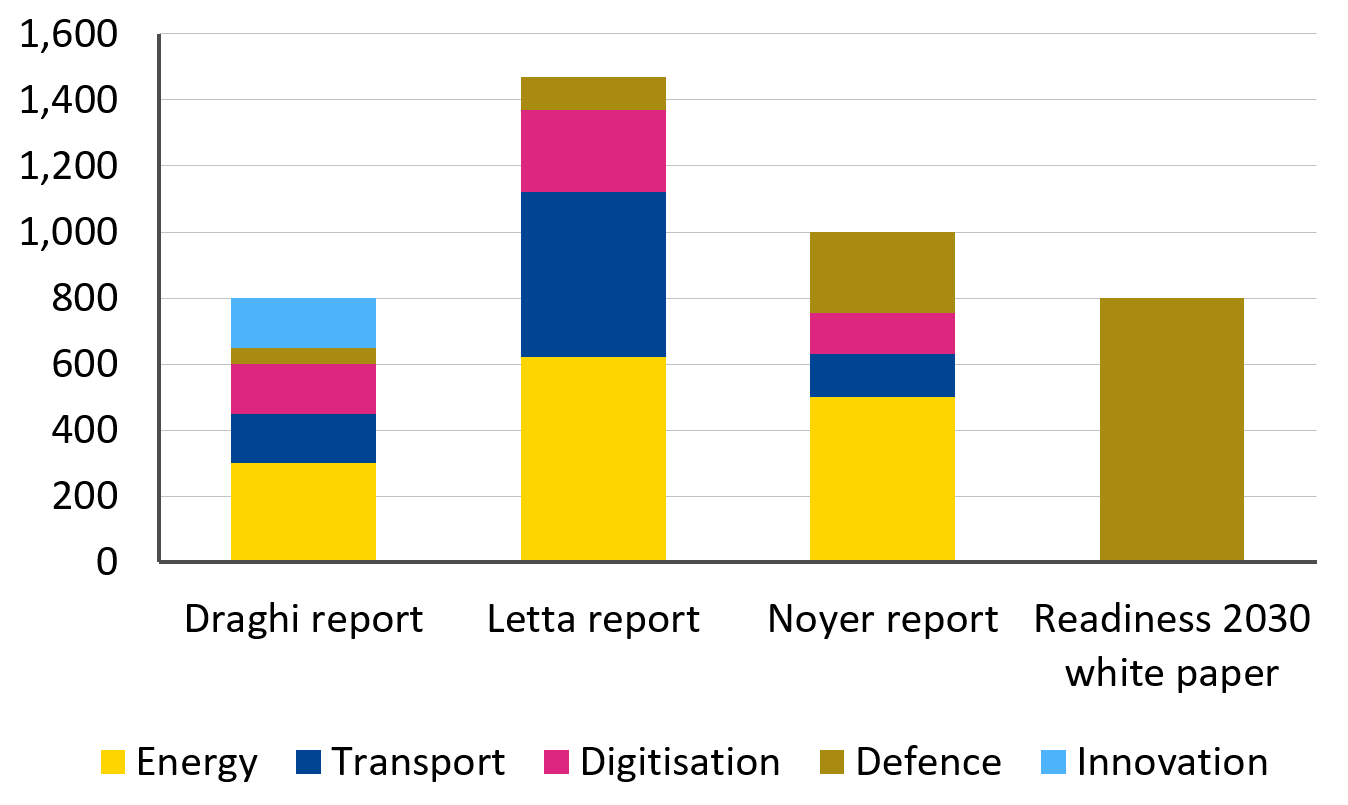

Recent high-level reports[1] have highlighted the challenges of shifting demographics and geopolitical landscapes that Europe must navigate while also financing the digitisation and green transition. Beyond this, the European Commission estimates that additional defence spending needs alone may eclipse previously estimated aggregate spending requirements (Figure 1).[2] Across the various reports, estimated financing needs vary in both amount and composition.

Figure 1: High-level reports have identified varying financing needs to transform the economy

(financing needs until 2030 in € billion)

Sources: Mario Draghi “The Future of European Competitiveness” report (2025), Enrico Letta “Much more than a market” report (2024), Christian Noyer “Developing European capital markets to finance the future” report (2024), and European Commission “White Paper for European Defence – Readiness 2030” (2025)

While expectations are high for the private sector to mobilise most of the required capital, it cannot shoulder the burden alone. Given that a number of the investment areas qualify as public goods, the public sector will also be expected to contribute. Such a coordinated effort will increase the supply of sovereign debt, ultimately begging the question as to who will absorb it.[3]

Sovereign-bank nexus has weakened and should not be rekindled

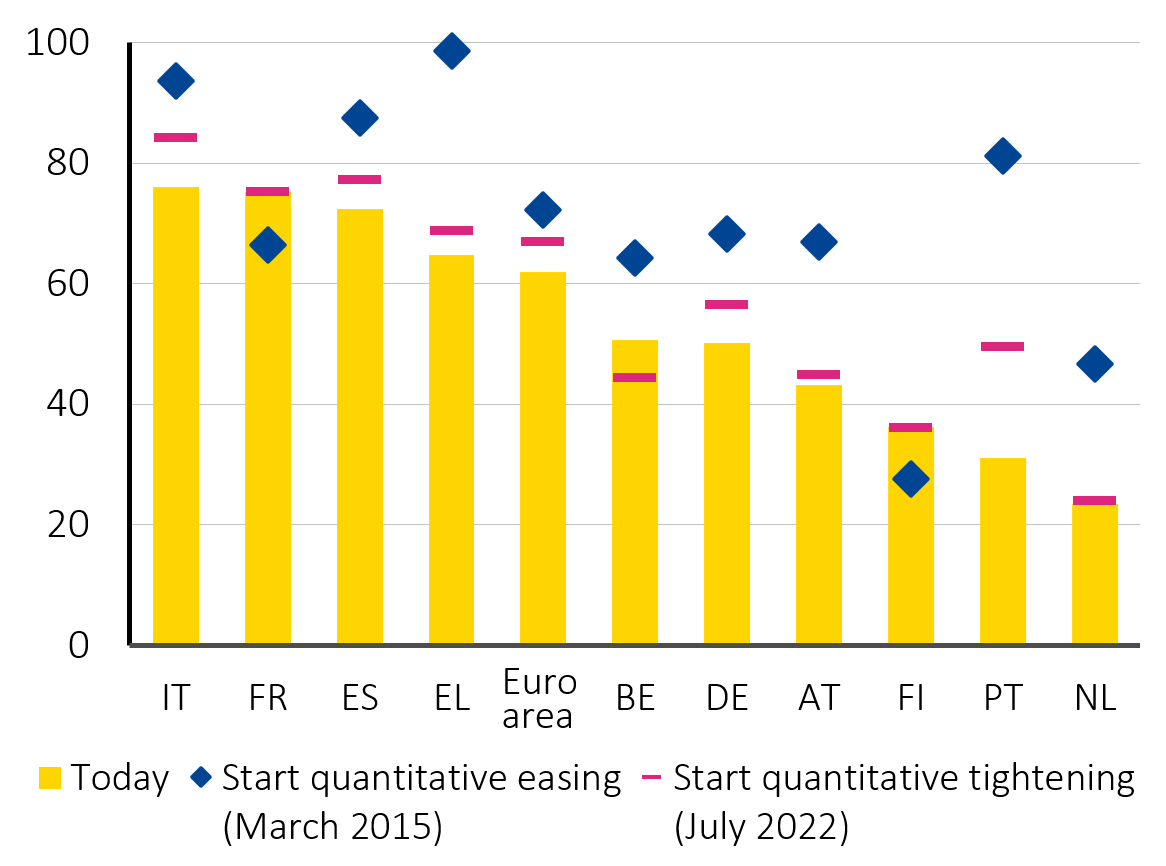

In the past, banks were a common buyer of sovereign debt, especially domestic debt. While on paper sovereign debt is often considered risk free, practice shows that this is not the case, as evidenced by the European sovereign debt crisis for instance. Where banks hold large quantities of sovereign debt, and concerns on the viability of this debt push down its price, the corresponding market value losses spill over into problems for the banking sector. As a result, banks’ lending capacity becomes constrained, thereby impeding their ability to serve the real economy, starting a self-enforcing doom loop of economic deterioration.[4] The Eurosystem began a period of quantitative easing and purchased a significant amount of European government bonds (EGBs) between March 2015 and July 2022, thereby crowding out European banks and reducing their share of EGBs from 21% to 15% (Figure 2a,b). This has ultimately weakened the sovereign-bank nexus.

Figure 2: Euro area government debt securities: an evolving and heterogenous investor landscape

2a: Evolution of sectoral holdings of government debt securities

(market shares in %, issued by 10 euro area countries)

2b: Investor base by sector for 10 euro area countries

(market shares in %, as of Q1 2025)

Note: Aggregate based on a subgroup of 10 euro area countries for which data is available prior to the start of the European Central Bank’s (ECB) quantitative easing. See endnote three for further details on government debt securities holders. Countries’ ratings are the average from the ratings of Fitch, Moody’s, and S&P.

Source: ESM calculations based on ECB data

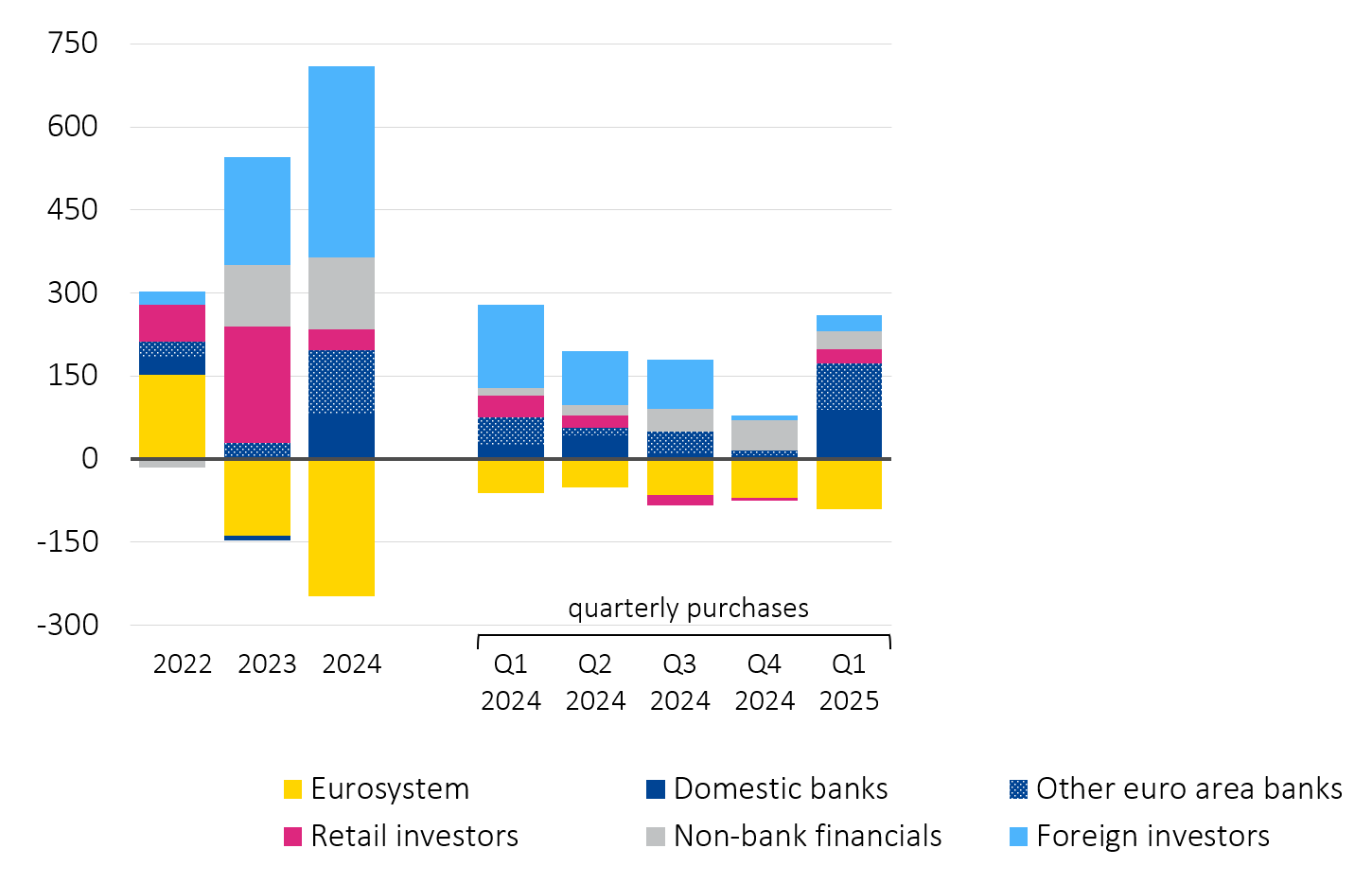

Banks resume sovereign bond purchases and increasingly look beyond national borders

Following a spike in inflation, the Eurosystem transitioned to quantitative tightening, stopping net asset purchases in July 2022 and ceasing the remaining reinvestment redemptions at the end of 2024.[5] This meant that other investors had to step in to fill this gap. Euro area banks have re-emerged as major purchasers of EGBs, particularly in 2024 and even more so in the first quarter of 2025 (Figure 3). During that quarter, banks acquired approximately €174 billion, nearly matching their total annual purchases of 2024. Notably, banks have been increasingly buying non-domestic EGBs, which account for around 60% of their total purchases since Q2 2022. As a result, the domestic concentration of banks’ sovereign bond portfolios has declined, despite the overall increase in banks’ EGB holdings since mid-2022 (Figure 4a).

Figure 3: Euro area banks’ renewed interest in EGBs, with record acquisitions in early 2025

Net purchases of government debt securities by investor category

(10 euro area countries, in € billion)

Notes: Subgroup of 10 euro area countries for which data is available prior to the start of the ECB’s quantitative easing. See endnote three for further details on the composition and categorisation of government debt securities holders.

Source: ESM calculations based on ECB data

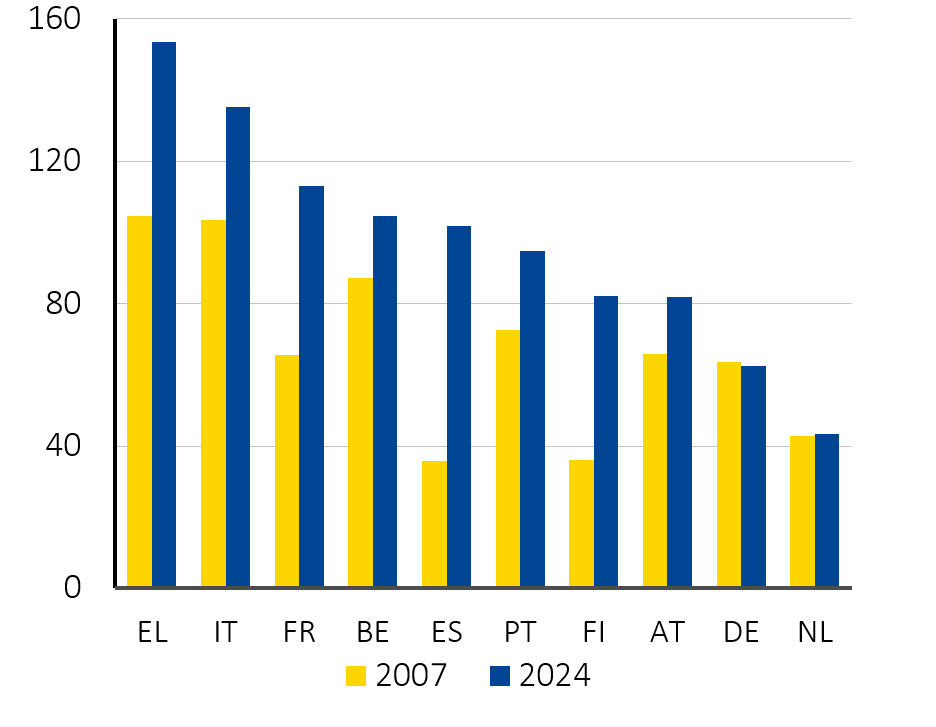

This development is welcome from a financial stability perspective as it reduces the risk of a feedback loop between banks and their sovereigns in times of stress, particularly now that these sovereigns have become more indebted (Figure 4b). While European banks’ market share of EGBs remains lower than a decade ago (17% versus 21%), it would be desirable to further diversify the investor base for sovereign debt, rather than increasing banks’ exposure and possibly rekindle the sovereign-bank nexus.[6]

Figure 4: Bank holdings of government bonds: declining home bias but rising sovereign risk

4a: Domestic EGB holdings as a share of total EGB holdings by banks in the reference country

(in %)

Source: ESM calculations based on ECB’s BSI data

4b: Outstanding sovereign debt as a share of gross domestic product

(in %)

Source: Eurostat

International investors are back, but opportunities come with challenges and risks

As euro area demand alone cannot absorb all net sovereign issuance, foreign non-euro area investors have long been — and will remain — essential to diversifying the sovereign investor base and lowering borrowing costs. Historically the dominant holders, foreign investors saw their share fall sharply during quantitative easing and the decade of ultra-low yields, from around 37% in 2015 to 21% by mid-2022 (Figure 2a). With the Eurosystem no longer buying EGBs, they stepped up their purchases, attracted by higher returns across the region.[7]

Since mid-2022, international investors have been the largest buyers of EGBs, particularly those issued by Germany, France, Finland, and the Netherlands, as they initially sought to lock in high yields ahead of an expected easing cycle. With the ECB having cut its policy rate at a faster pace than other major central banks, 200 basis points compared to 100 basis points for the United States (US) Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, foreign demand has begun to soften since late 2024 (Figure 3) and their appetite appears more selective. While France saw outflows and demand for German bonds remained muted early this year, net purchases shifted towards Italy, Spain, and Portugal, where yields remain attractive even after currency risk is hedged.

Foreign investors form a diverse group with differing motives, yet tend to favour liquid, high-quality papers (Figures 5a). Private investors, such as investment funds, primarily seek returns, while official investors — mainly foreign central banks — hold sovereign bonds as foreign exchange reserves, aiming to balance safety, liquidity, and returns. Central banks’ allocations, though still largely guided by trade links and foreign debt issuance, are increasingly shaped by geoeconomic considerations, including liquidity and credit risks arising from geopolitical shocks. Beyond economic rationales, political factors may also influence their decisions, posing risks to euro area external financing, especially as around one third of foreign holdings of EGBs are held by central banks in geopolitically distant jurisdictions.[8]

Looking ahead, with volatility now a defining feature of the global landscape and interest rates stabilising above zero in most major economies, a key question is whether foreign investors can be relied upon to absorb rising euro area sovereign issuance. While their share has recovered to around 24%, it remains well below their pre-quantitative easing levels, leaving ample room for further inflows. At the same time, growing concerns over US fiscal sustainability and political uncertainty are prompting investors to gradually diversify away from US dollar assets.[9] In this rebalancing, the euro is well-positioned to gain traction — not only as a diversifier, but increasingly as a credible safe haven supported by more predictable policy, stronger institutional fundamentals, and a demonstrated ability to manage crises. Seizing this opportunity, however, will require reinforcing the region’s foundations through deeper capital markets, a higher supply of safe assets, and fewer investment barriers.[10]

Figure 5: Investors are driven by different motives when investing in sovereign debt

5a: Foreign investors tend to favour higher-rated sovereign debt

(foreign-held sovereign debt securities by external credit rating, share in % as of Q1 2025)

Note: The rating is the average from the ratings of Fitch, Moody’s, and S&P.

Source: ESM calculations based on ECB data

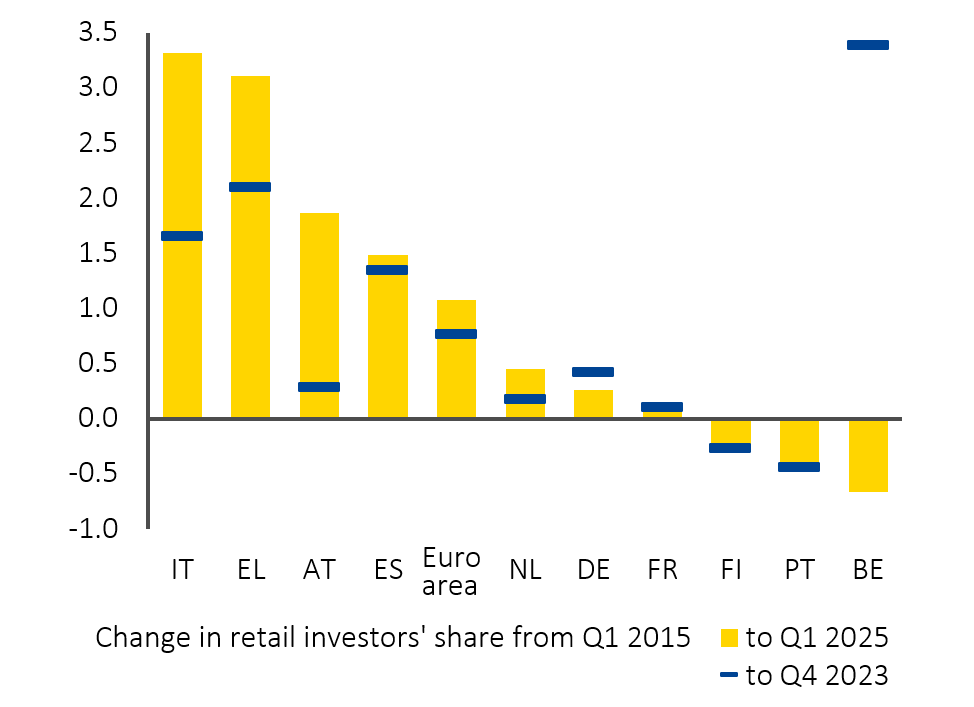

5b: Retail investors’ share of sovereign debt surpasses pre-quantitative easing levels

(in percentage points)

Notes: Aggregate based on a subgroup of 10 euro area countries for which data is available prior to the start of the ECB’s quantitative easing. Positive numbers indicate that the holding share of retail investors, as of the latest data, is already above its pre-quantitative easing level (Q1 2015). We also examine change as of Q4 2023, as some governments (such as Belgium) introduced temporary initiatives to encourage banks to raise their deposit rates.

Source: ESM calculations based on ECB data

A broader role of households could be a mutually beneficial endeavour

Households could play another important mutually beneficial role in absorbing the additional sovereign debt.[11] First, they too were crowded out by the Eurosystem’s asset purchase programmes, creating space to reclaim. Indeed, recent data show a return of retail investors to sovereign debt markets, even beyond pre-quantitative easing levels for some countries (Figure 5b). Second, household debt absorption can help contain borrowing costs, supporting the public purse and social cohesion.[12] Third, bonds often yield more than bank deposits, drawing larger holdings, where this advantage is compounded by preferential tax treatment (Figure 2b).[13]

Yet, where retail participation increases subsequentially, households’ home-bias towards their sovereign warrants attention, as it tightens the link between government solvency and private wealth. Against this backdrop, initiatives such as savings and investments union are welcome to strengthen retail investor participation while encouraging diversification. Examples such as the Dutch or Swedish savings and investment accounts and a simplified treatment of cross-border taxation[14] could reduce this home-bias by channelling savings from domestic to other euro area capital markets as well as other asset classes. With such diversification, greater household involvement can broaden and stabilise the sovereign investor base, as households are typically less prone to sell during periods of market stress.

Completing savings and investments union: a path to diversifying sovereign investor base

While net issuances have been smoothly absorbed since the end of quantitative easing — with foreign and retail investors playing key roles and banks reemerging as strong buyers — the vast investment needs ahead raise concerns about reigniting the sovereign-bank nexus, something closely monitored by the ESM. Diversifying the investor base is therefore crucial to mitigating this risk. To support greater participation from households and foreign investors, policy initiatives such as savings and investments union should be pursued without delay. Doing so would remove investment barriers within the region, thereby deepening capital markets and helping finance productivity-enhancing investments, boosting Europe’s investor appeal. The benefits thereof are mutual: foreign investors would find stable investment opportunities and households can earn higher yields while diversifying across geographies and asset classes. As a result, the ownership of sovereign debt would naturally diversify and possibly contain rising yields at a time of quantitative tightening despite public spending pressures.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Pilar Castrillo, Paolo Fioretti, Nicoletta Mascher and Rolf Strauch for valuable discussions and comments to this blog post, and Raquel Calero, Cédric Crelo and Anabela Reis for their editorial review.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager