Firms’ profits: cure or curse?

Due to disruptions in global supply chains and higher energy prices, firms have been faced with sharp cost hikes over the last three years. Overall, corporates appear to have weathered these challenges showing recent profit margins increasing to historic highs. Higher profit margins helped reduce firms’ financial vulnerabilities by strengthening their balance sheets and eventually supporting financial stability. But they simultaneously contributed to the rise in inflation.

Looking ahead, a steady normalisation of margins is expected. However, if a wage-price spiral emerges – where wage increases trigger price hikes which, in turn, instigate further wage increases and so on – vulnerabilities could rise, eventually leading to a double negative effect of falling profit margins and slower economic activity. This scenario would amplify financial stability risks.

Despite record surge in expenses, firms saw increased profits

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, disruptions in global supply chains and the extraordinary surge in energy prices led to a sharp increase in firms’ input costs. Corporates can react to higher input costs in two ways. First, they can pass the higher costs to the consumer to avoid a profit squeeze. Second, in the most extreme cases, a spike in costs can force firms to cut production, resulting in employment losses and further economic deterioration. Corporate vulnerabilities can lead to repercussions on the financial sector and public finances. At the ESM, we analyse these developments to detect any potential risk and vulnerability to the economy and financial stability as early as possible.

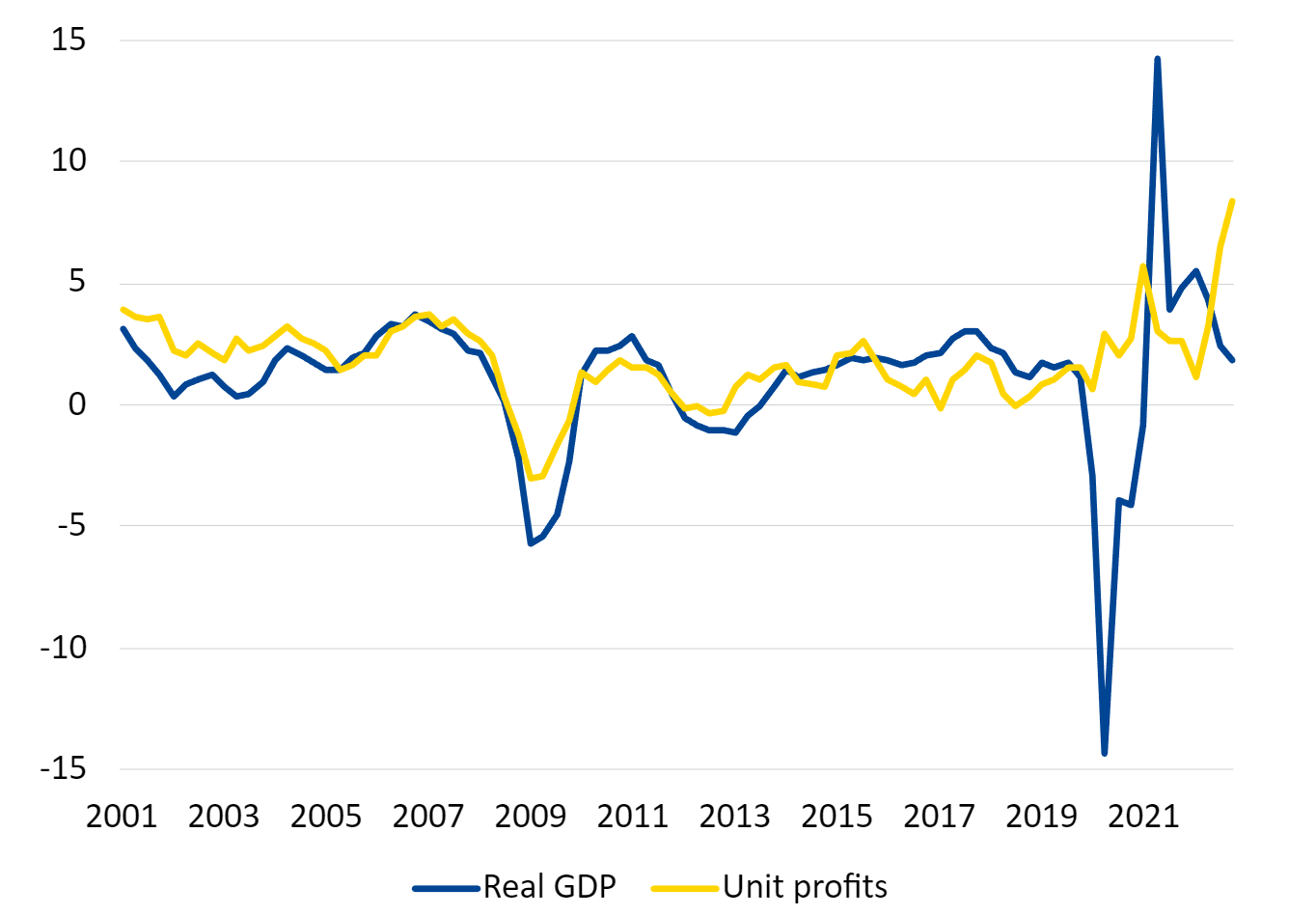

Firms were able to weather the cost pressures and increased their profit margins and profits. On average, corporate profits grew by around 10% in 2021 and in 2022, well above the pre-pandemic historical average.[1] Despite the surge in energy prices, firms’ profit margins also accelerated sharply.[2] Firms were able to hike final prices, more than compensating for higher costs (although with high heterogeneity across sectors) in a period of decelerating economic activity. This is an unusual pattern, as both profits and profit margins tend to move in line with economic growth (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Decoupling of unit profits and economic growth as of 2021

(in %, year-on-year)

Note: Unit profits are calculated as gross operating surplus over real GDP.

Source: ESM based on Eurostat data

What’s behind the surge in profits?

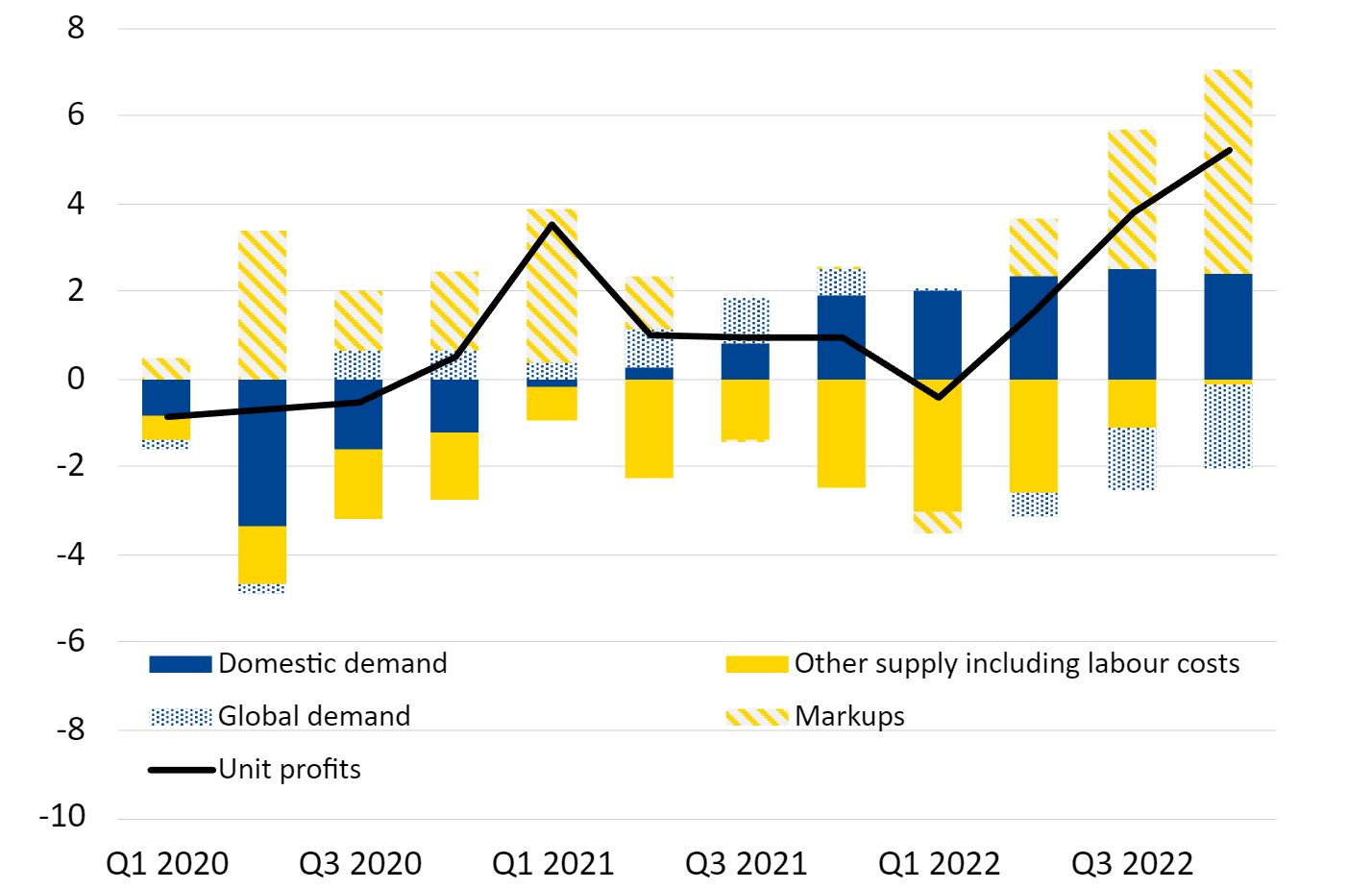

We use an econometric model to discern the underlying factors of profit developments.[3] We identify two main driving forces of the recent performance of profit margins (see Figure 2). The first is related to domestic demand. The lasting effects of the post-pandemic recovery coupled with the government fiscal support are some of the factors that, by sustaining domestic demand, could have contributed to the increase in profit margins. The second factor occurs within firms: the rise in firms’ pricing power – their ability to pass changes in costs to the consumer without harming sales – both domestically and abroad. This factor became the most important driver of profit margins since the beginning of 2022.

Last year, the rise in pricing power was strong enough to more than offset the negative impact from weaker global activity and other supply factors, including the acceleration of wages. Rapidly increasing prices on the back of a generally visible supply shock and high uncertainty about the overall magnitude of energy shortages and future cost pressures have seemingly created an atypical macro-environment. This exceptional situation could have allowed firms to increase prices aggressively and expand their margins. But these factors are temporary, and the economic situation is expected to normalise, in part due to improved supply conditions.

Figure 2: Domestic demand coupled with strong firms’ pricing power lifts profits despite drag in global demand and high costs

(annual growth rates, deviation from model mean in percentage points)

Source: ESM estimates based on a Vector Autoregressive model using Eurostat data

Two sides of the same coin: firms’ vulnerabilities contained, but higher inflation pressure

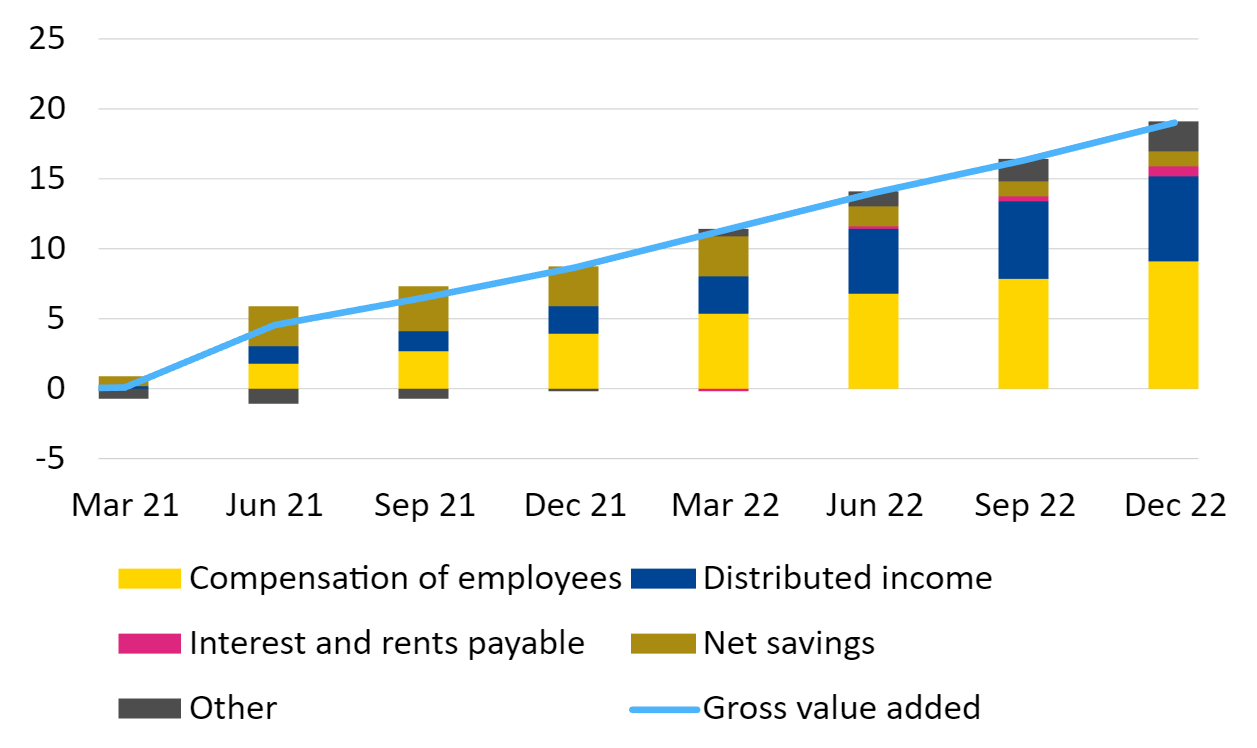

How firms allocate their revenues affects the resilience of their balance sheets. Since 2021, firms have been using revenues for three main purposes (see Figure 3). First, to cover the increase in labour costs. Second, to pay interest on debt, with the higher interest rates having little impact on profits thus far. Third, to distribute more income to owners to offset lower earnings during the pandemic. The remainder, income after costs and capital outflows (net savings), also recovered from the pandemic shock. These net savings were used to increase (physical and financial) investments and to strengthen firms’ balance sheets by reducing debt ratios (deleveraging).

Figure 3: Firms’ revenues go mainly to employees and owners

(gross value added in % relative to Q4 2020, contributions in percentage points)

Note: Other contains taxes less subsidies, less depreciation, plus property income, plus current taxes, plus capital transfers. Gross value added is defined as output (at basic prices) minus intermediate consumption (at purchaser prices).

Source: ESM calculations based on Eurostat

Firms’ profits helped to decrease debt-to-income ratios from the elevated levels reached during the pandemic, improving firms’ ability to repay debt.[4] Firms’ net savings were strong enough to foster their resilience by stabilising their indebtedness. Leverage fell – though from low levels – more than offsetting increases during the pandemic.

However, developments varied across firms and sectors. Profits were particularly high in those sectors (some manufacturing sectors and contact-intensive services, for example) that were harder hit by the pandemic. Being able to pass on high margins may have particularly helped those sectors. These firms have regained a stronger financial position from which to face future uncertainties and risks. Other sectors may have benefitted less.

Moreover, profit margins not only improved firms’ balance sheets, on aggregate, but at the same time added to inflation pressures. Though profit margins could remain elevated in the short term, they are likely to normalise when the reopening effects from the pandemic disappear and firms’ heightened pricing power dissipates. If the strong pricing power of firms persists and firms continue to pass increased costs – specifically labour costs – on to consumers, inflationary pressures will remain. Persistent inflation pressures may trigger further losses in employee purchasing power and lead to distributional conflicts.

Firms’ resilience must be preserved, managing cautiously their balance sheets

Firms’ healthy profit growth supports the resilience of nonfinancial corporations, eventually supporting financial stability, which is at the heart of ESM’s mandate. Given firms’ strong profits, it appears justified to phase out widespread support for companies put in place during the energy crisis, and to pursue a “targeted and temporary” approach for those firms still suffering.[5]

Healthy balance sheets reinforce strengths within the corporate sector and lay the ground for physical investment, supporting steady economic growth. The ongoing sharp increase in borrowing costs and strong wage growth could drag on firms’ margins and activity, specifically if global headwinds worsen.

As the European Central Bank has expressed, engaging in a wage-price spiral would be self-defeating.[6] Eventually, this would lead output and profit margins to fall – and the stabilisation of inflation would become more costly. This scenario would amplify financial stability risks as vulnerabilities could arise, eventually affecting citizens and financial institutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Raquel Calero, Pilar Castrillo, Niels Lynggård Hansen and Rolf Strauch valuable comments and contributions to this blog post.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager