Fiscal-monetary interactions: lessons from the recent experience - introductory remarks by Rolf Strauch

Rolf Strauch, ESM Chief Economist

Introductory remarks at panel discussion “Fiscal-monetary interactions – lessons from the recent experience”

Meeting of European Economic Association and European Econometric Society

Rotterdam, 27 August 2024

(Please check against delivery)

Let me compare fiscal-monetary interactions in the euro area and the US. I will focus on the period since 2019, which covers the response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and the subsequent energy price shock in Europe. This comparison is particularly interesting in view of the different nature of inflationary shocks combined with different government structures – federal in the US and a decentralised fiscal policy response in the euro area – and different fiscal policy reactions.

Some observers have considered US fiscal policy outperforming euro area fiscal policy. However, I will argue that (i) monetary-fiscal interaction was more efficient in the euro area than in the US; (ii) European policy measures were effectively geared towards the nature of shocks and structural issues in the euro area, and (iii) economic fragmentation because of decentralised fiscal policy remains an issue in our economic and monetary union in light of future challenges.

With two central bankers on the panel, Agnes (Benassy-Quere) and Klaas (Knot) and in line with the mandate of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), I will focus on fiscal policy rather than monetary policy aspects.

If we simply focus on GDP levels and growth, the US policy mix may appear more powerful. Following the Covid-19 shock, US GDP contracted almost 10% but recovered swiftly and reached its pre-pandemic level by the beginning of 2021. The contraction was larger in the euro area (almost 15%) and the recovery took longer (until the second half of 2021).

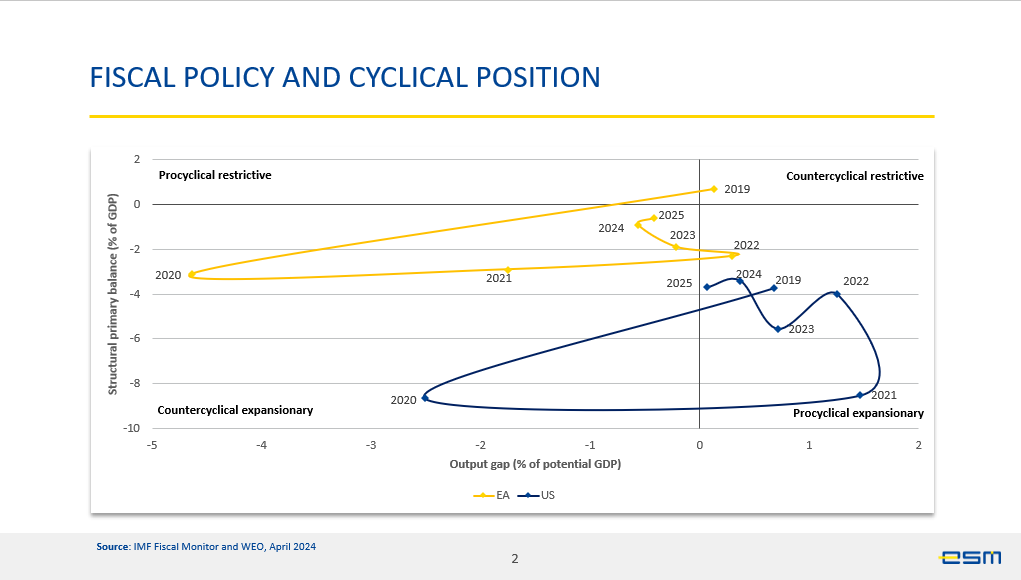

However, the US approach came at considerable costs. The headline fiscal deficit widened more in the US (about 8pps of GDP) than in the euro area (around 6pp of GDP) in 2020. And the US fiscal stance remained expansionary well into 2021, despite the more favourable economic position, pushing the GDP level above potential and turning pro-cyclical.

The US has been running a wider deficit through the period irrespective of the cyclical position. Before the pandemic, it stood at almost 6% of GDP. Fiscal stimulus was added in 2020 and again in 2023 when monetary tightening was already in full swing. The US will only return to its pre-pandemic structural primary deficit in 2024, according to estimates by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the deficit is expected to widen again in 2025.[1]

In the euro area, the policy mix was better calibrated. It helped stabilise the economy close to potential output, and it was more aligned with monetary policy. Effectively it appears that fiscal policy was more prevailing during the pandemic, where monetary policy was constrained by the zero-lower bound. During the recent inflationary period, monetary policy tightened rather drastically while the fiscal policy reaction was overall moderate at an aggregate level.

The explanation for this interaction stems partly from the nature of the shock. The pandemic pushed inflation and output in the same direction – and on that account can be considered a “demand shock”. The recent cost-of-living crisis was a typical “cost-push shock”, when inflation and output push in different directions. Standard fiscal policy instruments are not necessarily geared to such a constellation.

Let me emphasise that the choice of fiscal policy instruments was calibrated to the type of shock in Europe. The IMF has rightly termed them “unconventional fiscal policies”, which entailed substantive innovation, complementing monetary policy.[2]

During the pandemic, fiscal support focused strongly on the resilience of firms and workers. This approach was appropriate given the euro area's more rigid labour and product markets, effectively supporting employment and business stability through labour retention and firm guarantees. Without this focus, the economic frictions would have been too high to allow for a speedy recovery.

The response at European level was crucial, involving all European institutions including the ESM. Actions by the European institutions was essential in keeping market confidence contained; particularly the NextGenerationEU fund of the European Commission was set up to initiate structural reforms and investment to overcome structural weaknesses of the euro area economy. At the same time, these measures were designed with a deliberate re-distributional intention to support European countries suffering more from the crisis and low incomes.

Similarly, policy coordination at European level was important. In the fiscal area, although it is far from perfect, it sets the tone and a common narrative to which finance ministers could relate in the context of the crises.

As the energy crisis unfolded in 2022, euro area fiscal policy also had to compensate for the Terms-of-Trade (ToT) shock. The European Central Bank (ECB) estimated that discretionary fiscal policies not only supported growth, but also helped to mitigate inflationary pressures.[3] The IMF also found that the euro area fiscal measures were effective in keeping core inflation and inflation expectations lower, reinforcing the appropriateness of the euro area’s strategy in response to its specific economic conditions.[4] European policy coordination and initiatives led to improvements in the functioning of energy markets and energy savings.

Macro-economic consequences

What are the macro-economic and budgetary consequences of the different policy reactions?

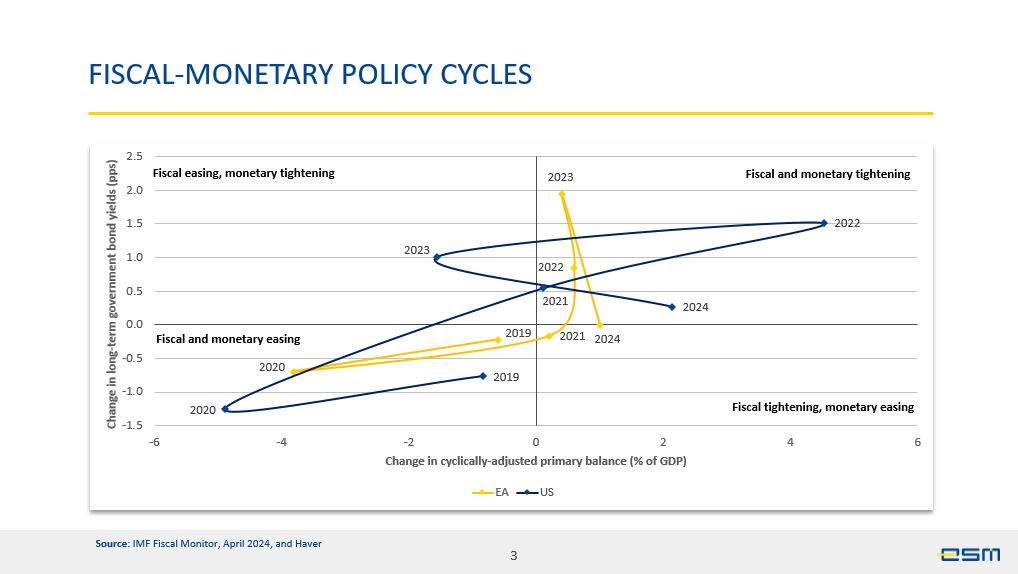

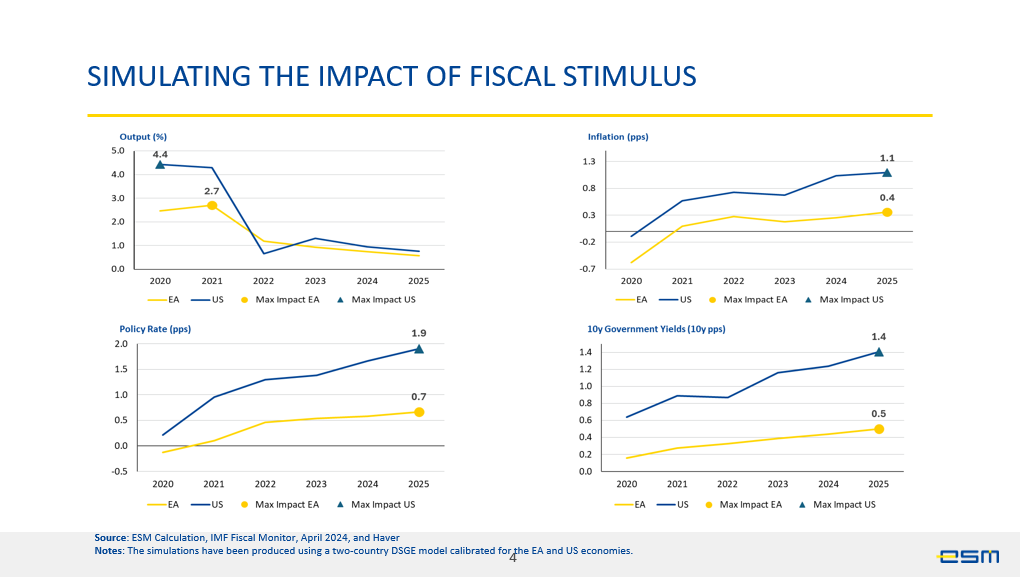

The overheating of the US economy was reflected in stronger inflationary pressures through 2021-2023. The US Federal Reserve had to raise rates earlier and more aggressively than the ECB. Eventually, the US Federal Reserve raised interest by 75bps more than the ECB through 2022-2023.

In the euro area, fiscal policy was less inflationary, and the spike in core inflation was less persistent, despite the more pronounced energy-price shock. This has put less pressure on the central bank to tighten monetary policy. In turn, monetary policy could be somewhat more supportive to fiscal policy while achieving its primary objective of containing inflation.

There are a few reasons why headline and structural inflation and growth figures can differ. Therefore, we ran some model-based simulations to gauge the macroeconomic impact of the different fiscal strategies in the US and the euro area. These suggest that the output gains were strong, but temporary and led to a more persistent rise in inflation and interest rates.

According to our estimates, the difference in fiscal policies can account for around one-third of the increase in the difference between US and euro area bond yields so far.

Long-term implications

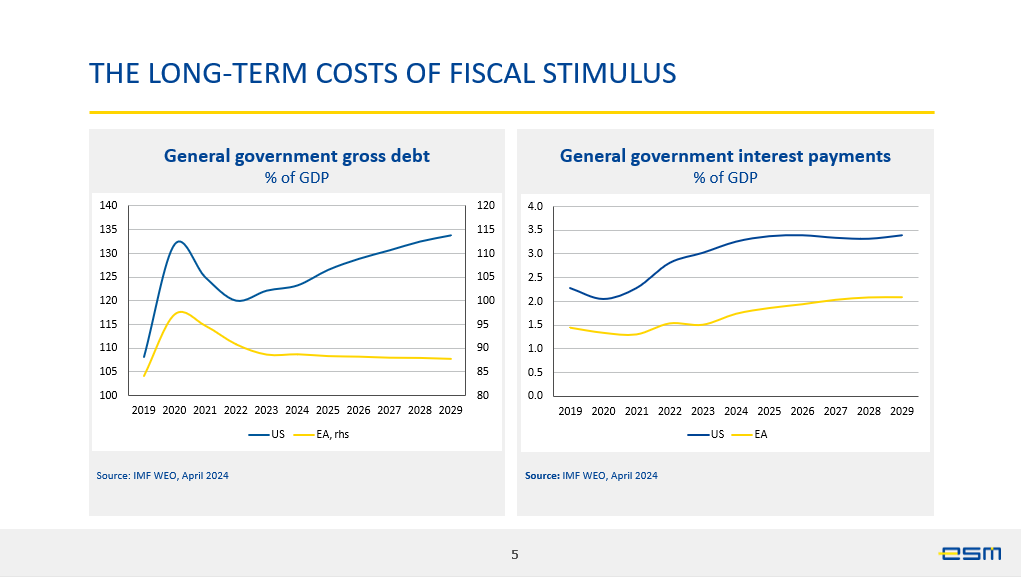

The US fiscal stimulus came at the expense of a more persistent increase in debt levels and borrowing costs. The increase in interest burden has been more contained in the euro area.

The US general government debt-to-GDP ratio rose by more than 20pp in 2020. Despite a partial reversal, it was still more than 10pp above pre-pandemic levels in 2022 and is expected to remain on an increasing path in the coming years. Euro area general government debt is currently less than 5% of GDP higher than before the pandemic.[5]

Rising debt levels in the US are partly due to a higher interest burden, which reflects the less efficient fiscal-monetary coordination and different debt management constraints and strategies. The government interest burden in the US is expected to remain above 3% of GDP through 2029, while the euro area average is likely to hover around 2% of GDP.[6]

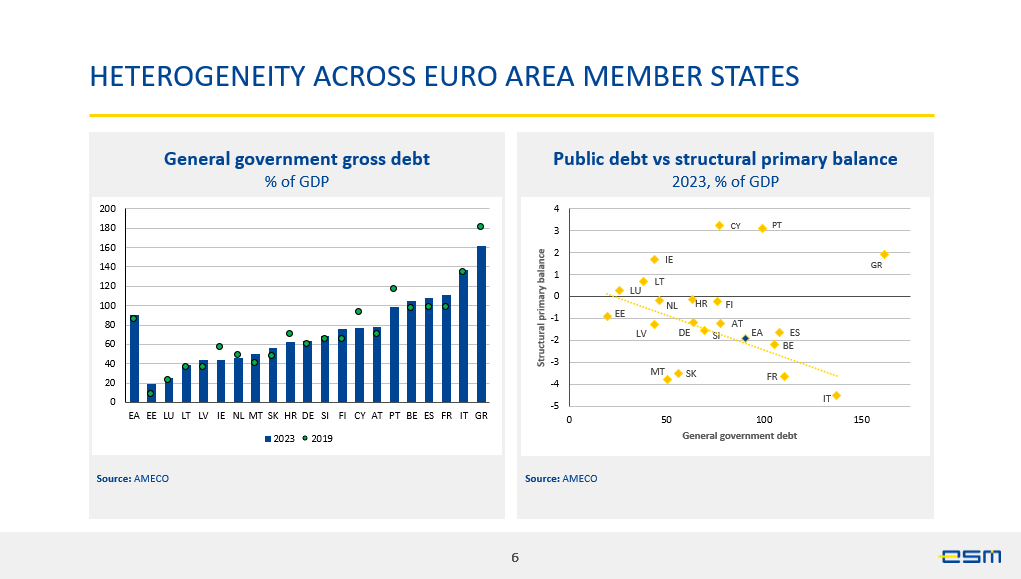

While the aggregate fiscal stance has played a useful stabilising role in the euro area, the cross-country distribution of fiscal easing in the euro area presents its own challenges. Some high-debt countries are left with little fiscal space and need to adjust while they cannot count on monetary policy accommodation any longer.

The budgetary position emerging from the pandemic and cost-of-living crisis risks leading to further fragmentation in the euro area given long-term challenges. Going forward, prudent fiscal policy is warranted to build buffers against future shocks.

The reformed fiscal rules provide an important anchor for long-term fiscal sustainability. Euro area member states must make sure that the new rules earn their credibility also in the eyes of government debt investors and financial markets.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the lack of a federal government has not prevented the euro area from applying a more efficient monetary-fiscal policy interaction compared to the US, with significantly lower fiscal costs and macroeconomically stabilising features.

Next to some policy innovation, vigorous support from European institutions was an important part of the picture and contributed to the successful management of the crises. European initiatives provided market confidence and financial relief.

The ESM has been part of these initiatives in its role as crisis resolution mechanism and added to market confidence.

Still, the remaining fiscal positions create an issue of economic fragmentation as the fiscal space remains limited in some countries to address future challenges. An effective implementation of the new fiscal rules and effective use of European resources is needed to address this issue.[7]

Footnotes

Author

Contacts