The ESM: euro area financial stability in safe hands - speech by Rolf Strauch

Rolf Strauch, ESM Chief Economist

“The ESM – euro area financial stability in safe hands”

Lecture at Erasmus School of Economics

Rotterdam, 31 January 2020

(Please check against delivery)

Good morning,

I am very happy to be here today at Erasmus University. Your School of Economics is among Europe’s top ranked economics departments. And this builds on a great tradition – the very first Nobel Prize in economics was awarded in 1969 to Jan Tinbergen, who was a professor at your school. Tinbergen is one of the founding fathers of modern economics.

What can you expect in the next 60 minutes? In my lecture, I will look at the achievements of European integration, including our common currency – the euro. Then I will show how the euro came under threat not so long ago, and what was done to overcome that threat. That is where the ESM comes into play with our mandate to ensure financial stability in the euro area. I will speak about its role during and after the crisis, how it operates, and what is set to change in the next few years. I will also show how the countries that received our loans have carried out extensive reforms, which helped them on their way to economic recovery.

European integration – what it means for us today

We experience the benefits of an integrated Europe every day. We can travel, live and work freely across borders, using the same currency wherever we go in the euro area. Beyond these aspects, we must also remember that an integrated Europe has given us a period of peace longer than any other in its recent history. This must mean a lot to all of us, considering that two world wars broke out in Europe, costing millions of lives and untold suffering and destruction.

When we think about EU integration, I believe that one of its underlying values – solidarity – makes Europe stand out from among other regions of the world. That value is at the core of many EU policies and institutions. Solidarity in crisis times is particularly important: Member States, as well as EU citizens, are not left unprotected if things go wrong.

European integration benefits us individually, but it also affects Europe’s standing in the world. We can observe that that the EU as a whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It has far greater political, economic and commercial influence than if its Member States had to act individually. Being integrated, acting together, speaking with a single voice – this brings large benefits to the EU countries and its citizens.

One important and effectively the most apparent symbol of European integration across the globe is our common currency, the euro.

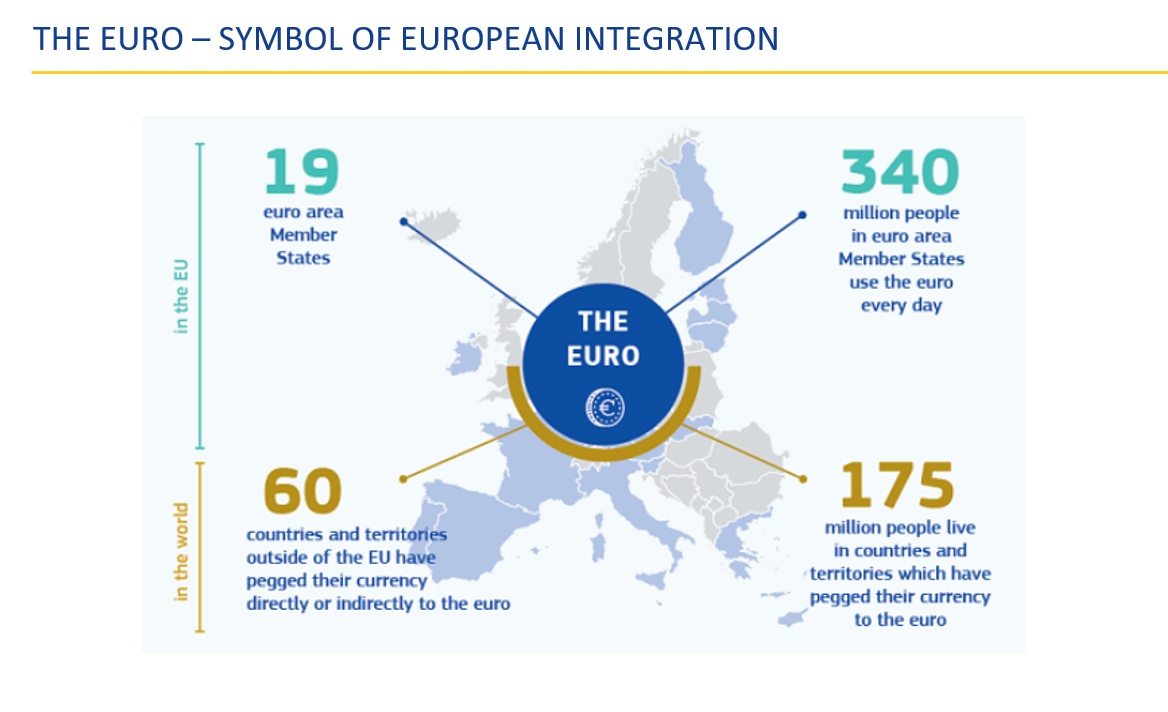

Euro banknotes and coins were introduced in January 2002. Today, you and 340 million Europeans share the single currency. I think I can safely say that for most of you in the audience today, the euro is the only currency you have ever used in your daily lives.

The introduction of the euro was not just a simple replacement of currencies – the guilder, the Deutsche Mark, the franc, the lira, and so on. Having a common currency requires a common monetary policy, and the need to coordinate to some extent economic and fiscal policies. It took a long and complex effort to make that happen. And as I will elaborate in more detail shortly, the founders of the euro did not foresee certain institutional gaps and difficulties that would come to challenge us later on.

Naturally, the euro is much more than just a convenient way of paying. It has brought a number of substantial benefits to our economies. Cross-border trade among euro area countries has increased as transaction costs have fallen. Price transparency has improved, leading to better functioning markets and better and cheaper products.

The end of exchange rate volatility is another major benefit brought by the euro. Foreign exchange upheavals were frequent in Europe from the end of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s until the start of Economic and Monetary Union. Only by this joining of forces can Europe ensure that it did not lose relevance on the global stage.

The euro is the second most important currency in the world, with a share of almost a quarter of global foreign exchange reserves. And with almost sixty countries and territories around the world either directly or indirectly pegging their currency to it.

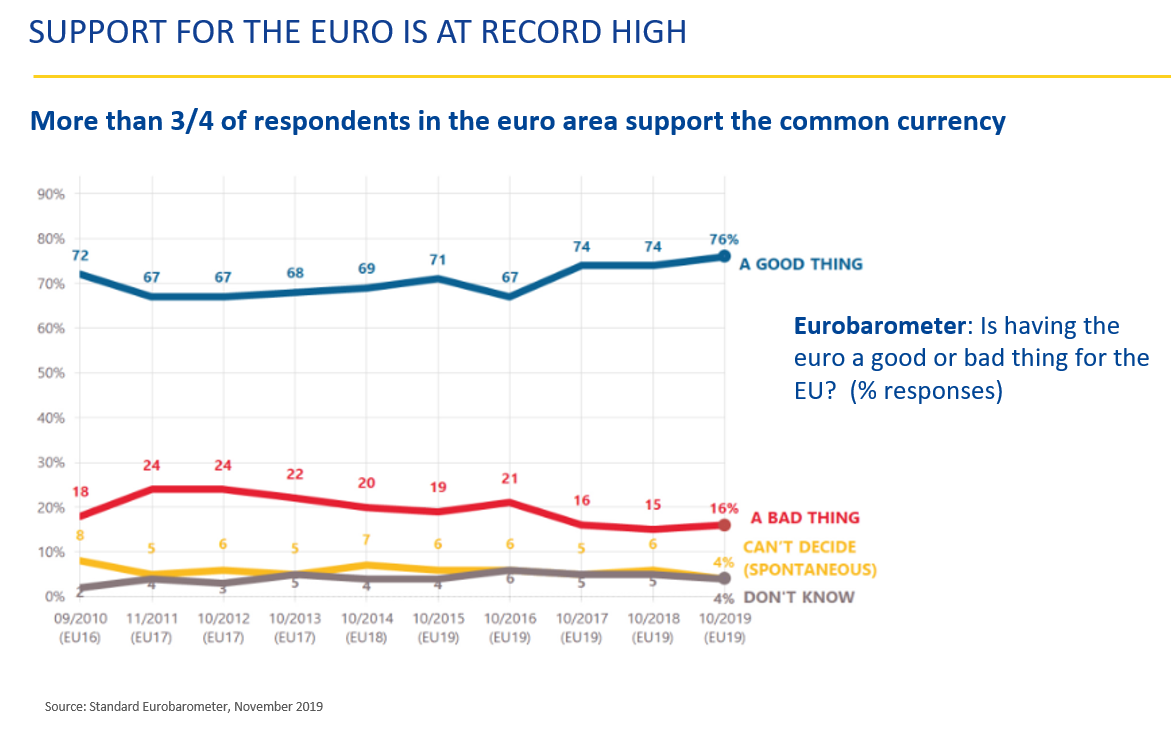

The euro enjoys strong support in Europe. More than three in four citizens think that the single currency is good for the European Union, according to the latest survey results. This is the highest support since surveys began in 2002.

As much as the euro seems a landmark achievement and permanent feature in our daily lives, it was only 10 years ago that some well-known economists (especially on the other side of the Atlantic) and market commentators were predicting that the euro would soon collapse.

Two crises

What was the reason for such gloomy predictions? We have to go back to 2008. The euro area experienced two major financial crises in the past decade. First, the global financial crisis affected Europe as it did in other parts of the world. As you may know, it originated in the United States, where banks irresponsibly provided huge amounts of mortgage loans to persons with a poor credit history. These loans were then repackaged as obscure financial instruments and sold to investors around the world.

Markets crashed when homeowners were not able to pay back their mortgages any more. This had major repercussions across the financial system, culminating with the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. It was one of the largest investment banks in the US. And its failure triggered huge economic shockwaves around the world.

And then, Europe was hit by a second crisis, whose roots are internal and go back to how Member States reacted to the introduction of the euro.

When some countries in Europe joined the euro, one effect was that long-term interest rates fell. As a result, governments, firms and households could borrow money very cheaply – and they did so. This led to very high levels of debt and real estate bubbles. Higher growth raised wages and prices, making their exports less competitive.

If a similar situation occurred in a country outside the euro area, the central bank could respond by devaluing its currency or raising interest rates. But in the euro area, that possibility does not exist because we share the same monetary policy. It is one of the main goals and benefits of monetary union to create exchange rate stability and avoid large fluctuations of exchange rates. The flip side of this is, of course, that the policy choice of devaluing one’s currency to gain competitiveness is taken away.

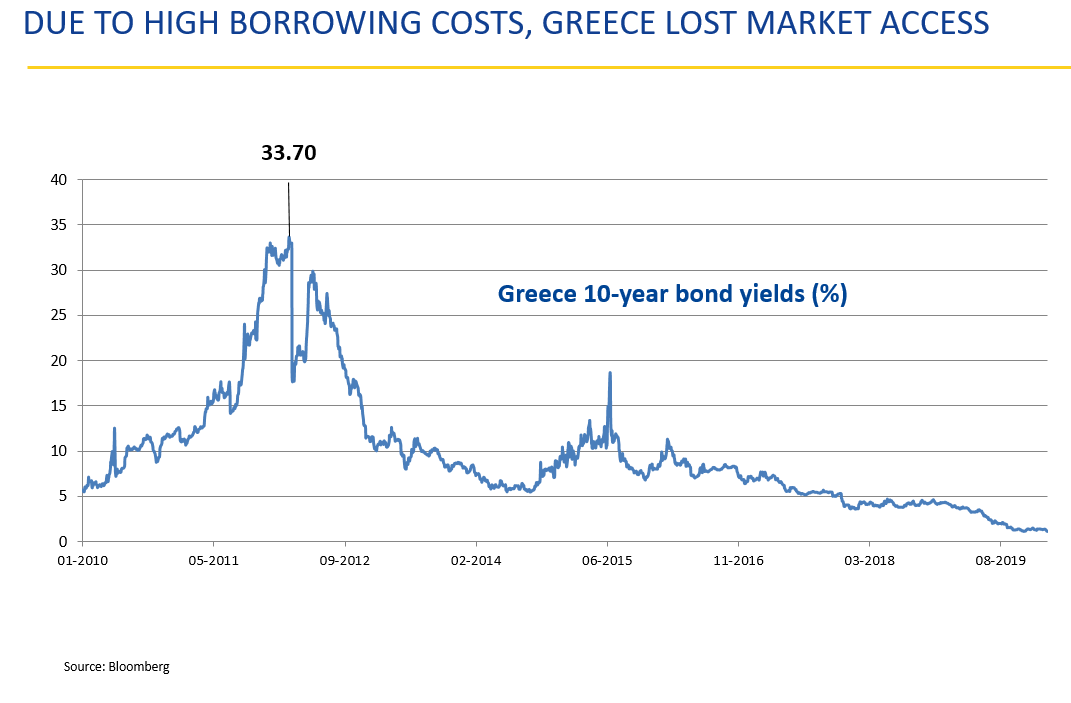

The situation was the most serious in Greece, where, as the world learned in 2009, governments did not reveal the true magnitude of their fiscal problems. Just to give you an idea: the initial Greek budget deficit for 2009 was officially forecast to be 3.7%. Now we know that it was four times larger, namely 15.1%. That is an enormous discrepancy, and it took everyone by surprise.

Let me take a moment now to explain something. Governments often spend more money than they receive through taxes and other income. To make up the difference, that is, to finance their budget deficit, governments have to borrow money. This is done through the issuance of bonds. Investors, banks, pension funds and others, buy these bonds, which means they are lending their money to a government.

As with any loan, if the lender considers that there is a significant risk that the borrower may not repay that loan, the cost of the loan will be much higher than for someone who is creditworthy.

Coming back now to the example of Greece, which had a huge budget deficit and thus needed very large amounts of loans to finance its budget. In the next chart we can see Greece’s 10-year government bond yields. This shows the interest rate that Greece would have to pay to borrow money for 10 years from private investors.

Looking at this chart, we can see how the yields were rapidly increasing in 2010 up to early 2012, when Greece would have had to pay almost 34% for a 10-year bond.

Naturally, it would have been impossible for Greece to do that – it would not have been able to afford such high interest costs. Even a level of 6% or 7% is usually quite elevated and creates a situation when a country may lose market access at affordable prices – that is, it can no longer afford to finance its deficit through the sale of bonds to investors.

Part of the financing that a government needs is used for repaying previous loans. That is how it often works – a government rolls over a bond, which means that when one bond is due to be repaid, the repayment amount is raised from selling a new bond.

In recent history, there have been cases when governments defaulted on their debt. It happened to Argentina several times, it happened to Mexico, to Russia.

But what about the euro area? The default of a euro area country without any financial support would mean that a government would be forced to make big cuts to government spending and ramp up taxes. But a default is a serious breach of trust. It is hard to imagine how a euro area Member State would be able to immediately start selling bonds denominated in euros again – investors would have serious doubts regarding the repayment capacity of such a country.

If we continue with that scenario, what would happen next? The default immediately affects everyone, including the banks – at home and abroad – which hold the government bonds as capital and use them as collateral to draw liquidity from the central bank. The life-line of monetary union is actually cut if the European System of Central Banks were not in a position any more to provide liquidity to the banking system. The defaulted country would have to leave the euro area and switch back to its national currency.

But what consequences would that have? Imagine that such a currency switch takes place. The economy of the country is in a very bad condition. People would immediately be trying to convert their savings and earnings to euros or dollars. In other words, runs on banks, bank closure and potentially the collapse of the payment system would occur. What happens to the value of the national currency? It plunges, of course. This would not only result in a huge loss in the value of people’s savings, but also in a sharp increase of the costs of critical imports such as medicine, fuels, food and other items.

Some people say that such revaluations are actually helpful. But this can be a very short-sighted view and it is not an easy escape. Afterwards governments are often left with terrible choices – making draconian cuts in government spending and have very tight monetary policy or risk hyperinflation. Either way, the economy suffers terribly and people feel extreme hardship, especially those that are most vulnerable.

It might have been assumed that in an economic union and even more so in the euro area as a monetary union, there must be some tools that could be used to help a country that finds itself in such dire circumstances. However, when the euro was created, its founders had not foreseen nor imagined that a country could lose market access and be on the brink of default. There were no institutional solutions, there was no rescue fund, no contingency plan. But if no action was taken, there was a very real risk that the dramatic scenario I just presented could materialise.

Let me come back to my example of Greece. In early 2010, it became clear that Greece could not handle its problems on its own and urgently needed financial assistance. It was in the interest of all to act at that moment: an exit from the euro area would have had a devastating effect on Greece. And it would have threatened financial and economic stability throughout the continent.

Preserving the euro area: EFSF and ESM created

Therefore, a rescue plan for that country was prepared, which involved bilateral loans from euro area countries to Greece, and also loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This assistance would help Greece to stay in the euro, smooth the fiscal adjustment, shield the banks from the risk of bank runs, and allow trade to continue. In short, prevent the economic “free fall” that otherwise could have occurred and threatened the euro area overall.

By the time this financial assistance package – known as the Greek Loan Facility – was agreed, problems were brewing in other countries as well. There was a real risk of financial contagion, that is the spread of market disturbances to other countries. This even undermined the stability of the euro area as a whole.

What was needed was a backstop: a systemic solution to ensure that euro area countries would have a ‘lender of last resort’ that could provide financing when no other options are available.

In May 2010, the leaders of the euro area countries reached an agreement on how to make that happen. They decided to establish a rescue facility with a lending capacity of €440 billion. It was designed as a temporary institution, able to take up financial programmes for a period of three years. This was the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), predecessor of the ESM. It was established as a private company under Luxembourg law, with the support from the euro area Member States as shareholders. Thanks to their guarantee commitments, the EFSF was able to raise funds for loans through the sale of bonds to private and public investors worldwide, for the loans it would give to countries in financial difficulties.

Initially, it was hoped that the mere existence of the new facility was enough to reassure financial markets that a break-up of the euro area was not going to happen. But after several months, the EFSF was called into action when a real estate bust sparked a banking crisis in Ireland.

In 2008, the Irish government decided to provide a guarantee to the country’s largest banks. This was a very risky course of action, considering that the banks’ liabilities amounted to 10 times Ireland’s national debt and more than twice the value of the economy.

The government also decided to strengthen banks’ capital to prevent their bankruptcy, which required expensive cash injections. This put a huge strain on public finances and the budget deficit was growing to alarming levels.

Investors then began charging very high interest rates on loans to the Irish government, knowing that it had to back the constantly growing banking losses. This is the point when Ireland, like Greece before, lost market access. They could no longer afford loans to refinance their budget.

In other words, as a result of bailing out the banks, the Irish government itself was forced to seek a bail-out. It requested financial assistance from the EU and IMF in November 2010. The EFSF provided loans of nearly €18 billion to Ireland as part of an international financial assistance package.

Several months later, Portugal became the third country to receive assistance during the euro crisis. Unlike some other programme countries, Portugal had suffered a long period of weak economic growth before the crisis. As a consequence of persistent current account deficits, Portugal had accumulated a large external debt, which was reflected in high household, corporate and fiscal debts. Wage growth above productivity gains contributed to Portuguese products becoming expensive abroad, which caused a drop in exports.

Investors were becoming more and more nervous as the crisis was spreading to more countries. This led to a deterioration of confidence and rising market pressures on Portuguese debt. Early in 2011, it became too expensive for the country to borrow money on financial markets. In April of that year, Portugal requested assistance from the EFSF, the EU, and the IMF.

Now the story of the crisis leads us back to Greece. As you remember, in 2010 they received a package of financial assistance, and the Greek government made major efforts to implement the reforms which were tied to those loans. The pension system was overhauled, public sector benefits were reduced, and public financial management was improved.

However, the challenges confronting Greece remained significant. They had a wide competitiveness gap, a large fiscal deficit, a high level of public debt, and an undercapitalised banking system. The economic recession proved to be more serious and damaging than expected. The financial assistance was not sufficient for Greece to make the necessary adjustments and to regain market access.

And what was especially critical: Greece’s public debt was recognised as unsustainable, that is too high for the country to be likely able to repay. Therefore, a restructuring of debt held by private creditors became necessary to bring the total debt level down and allow official creditors like the EFSF to provide additional support helping Greece to tide them over into a better economic situation.

In what was called the Private Sector Involvement (PSI), 97% of privately held Greek bonds (with a value of nearly €200 billion) took a 53.5% cut of their nominal value. This meant that the investors which had purchased those bonds accepted a loss of €107 billion. As a result, Greece’s debt stock was reduced by that amount, which opened the way for further assistance.

Additional time and money were required to continue Greece’s fiscal consolidation efforts and pursue reforms that would bring growth and improve competitiveness. Therefore, a second programme for Greece, provided by the EFSF and IMF, was agreed in the beginning of 2012.

As I said earlier, the EFSF was established in 2010 to provide loans only for a period of three years. It soon became clear to euro area members that Europe would need a crisis resolution mechanism well beyond that three-year period. What was needed was a permanent solution, rather than a temporary resource.

That is why in the beginning of 2012, euro area Member States signed a treaty establishing the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). We are an intergovernmental organisation, comprising the euro area countries – not an EU institution, like the Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB) or the European Investment Bank. I will tell you more about how it works a bit later.

The ESM started operating in autumn 2012. Almost immediately, we were called in to provide assistance to Spain. There had been a massive construction boom in that country, with house prices nearly tripling between 1997 and 2008. The bubble was fed by cheap loans from banks. When the bubble burst, real estate prices collapsed. As in Ireland, clients struggled to repay mortgages. And as a result, banks were left with huge losses. In addition, the Spanish government, with a budget deficit of over 10%, had little room to manoeuvre.

While Spain never lost access to market financing, raising money on financial markets became increasingly expensive, and there was a real risk that the country would slide into a crisis. In an attempt to calm uncertainty, and quickly address the banking issues, Spain requested assistance from the ESM in 2012. Unlike previous programmes, this was a loan to the government specifically for the purpose of bank rescue.

The following year the ESM was busy again. We had to provide emergency loans to Cyprus. The main problem of this island nation was an oversized banking sector and big exposures to Greece. The largest banks had substantial capital losses and Cyprus experienced high current account deficits and a loss of competitiveness. This excessive budget deficit limited the government’s ability to help the banks. As a result of these problems, Cyprus was no longer able to borrow money from investors and requested financial assistance.

By 2015, for the euro area as a whole, things started to look much better. Economic growth recovered to solid levels. But in the beginning of that year, political developments in Greece had a major impact on the course of events.

Greece was a special case during the euro area crisis. It had to cope with greater difficulties than the other four programme countries. Its starting point was much worse. But thanks to several years of extensive reforms, economic growth had returned, unemployment was falling and the government was able to sell bonds again to investors.

Then, in early 2015, a new government came to power in Greece. There was an attempt to halt the reform programme Greece had previously agreed to. The result was that the country dropped back into recession. What made the situation even more dramatic was that the financial assistance programme, which started in 2012, was scheduled to end. But due to deepening economic problems, it became clear that Greece would need more loans.

This of course would mean that the government would have to revert to the agreed reform path. But negotiations proved very difficult, and in the summer of 2015 there was again a real threat that Greece would default on its repayment obligations. Fortunately, after the appointment of a new finance minister, the deadlock was broken and an agreement was reached. The ESM would finance a new financial assistance programme for Greece, which was completed in 2018.

As you can see on this slide, the EFSF and ESM have paid out almost €300 billion in loans. This is a huge amount of money.

There is a misconception you sometimes hear about that we are lending money coming from European taxpayers. No – that is not how it works. To finance our loans, we have to borrow the money first. This is done by selling bonds to investors, mainly institutional investors such as banks, insurance companies, and pension funds.

The ESM can borrow money at very low rates because our bonds are backed by €80 billion in capital paid in by Member States. This serves as security or a safety buffer. And it reassures our bondholders that they will be repaid when the bonds mature. For this reason we can raise money at very low interest rates. These interest rates are well below what the countries would be charged by investors as you saw on a previous slide.

The €80 billion in paid-in capital that we receive from our Member States can never be used for loans. The ESM invests these funds in very safe assets to preserve its value.

When the ESM agrees to provide loans to a country, we do not pay out all the money at once. It is paid in instalments over a period of three years. ESM financial help is linked to conditionality: this means that in exchange for money, countries must carry out reforms to repair their economy. The weaknesses which led to a crisis situation in a given country must be addressed.

As a rule, during the course of a programme, an assessment of how these reforms are going is conducted regularly by the European Commission, the ECB, the ESM, and the IMF – if the latter participated in the programme. Successive loan payments can only be carried out if that assessment is positive.

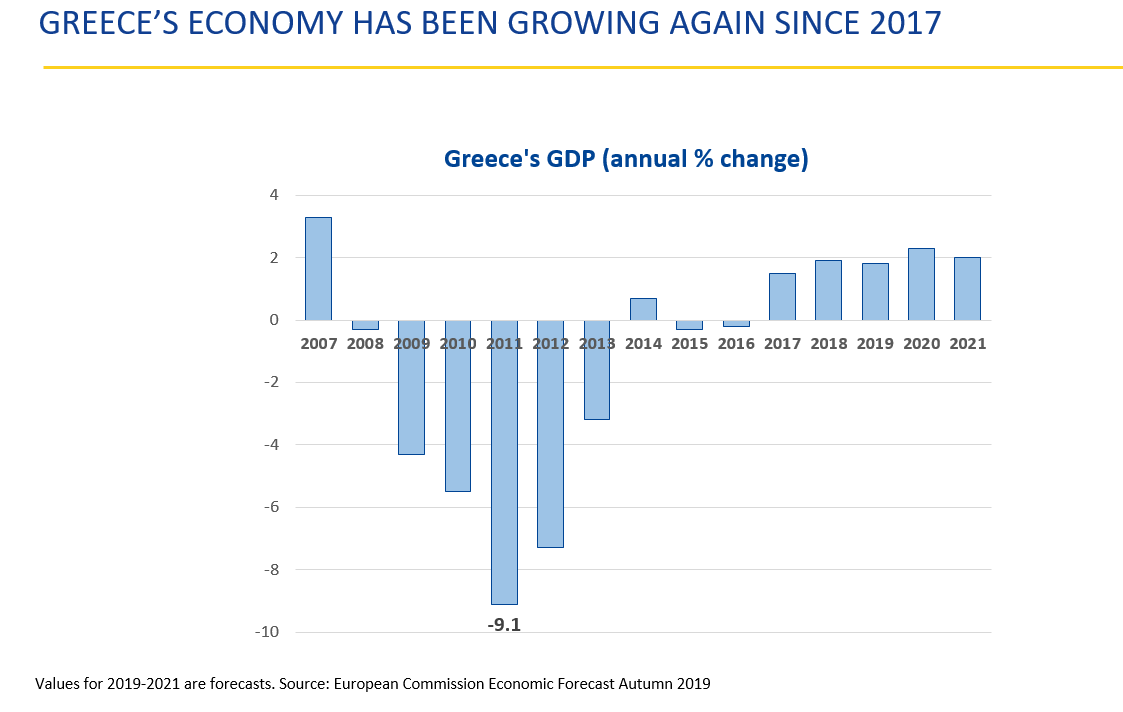

The experience of EFSF and ESM programmes shows that conditionality works. All of the former ESM programme countries regained market access. This was possible thanks to reducing debt, solid economic growth, improved competitiveness, and a stronger banking sector. Let me show you how economic growth has evolved in Greece.

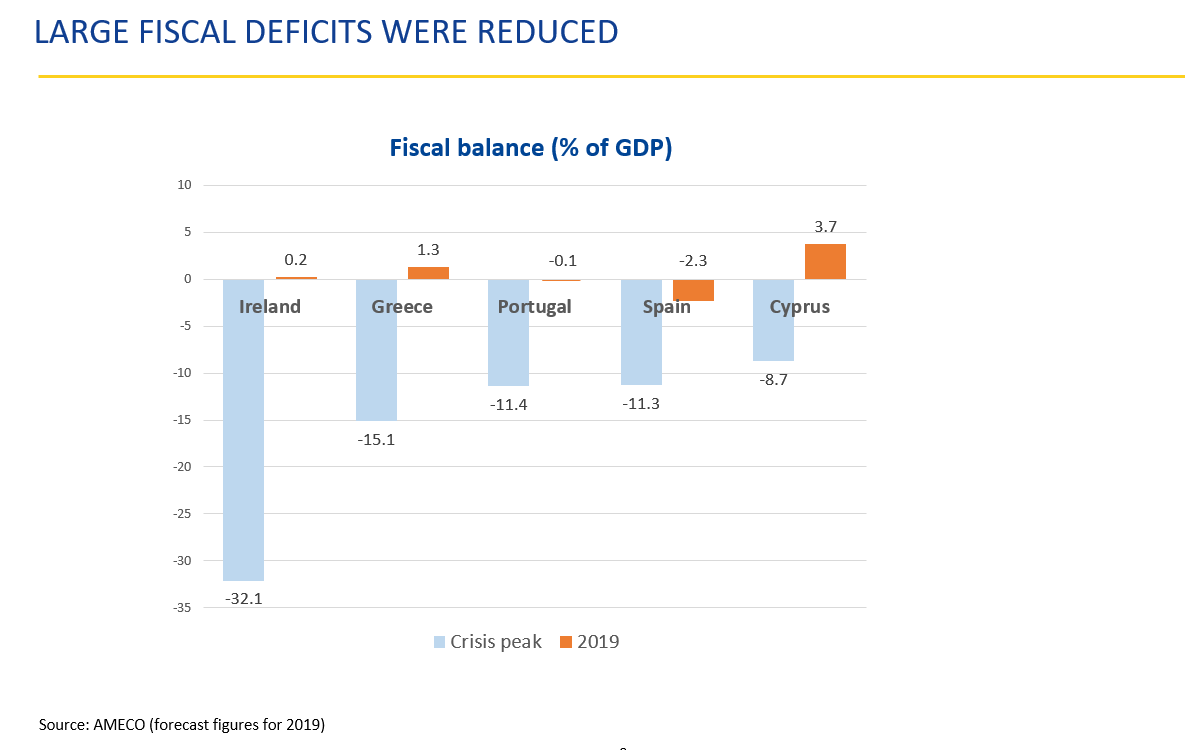

Economic growth has returned in all five programme countries, and other key indicators show a huge improvement since the euro debt crisis. Unemployment is much lower, and the very large budget deficits that were recorded during the peak of the crisis are have been reduced, as you can see in the chart.

Coming back now to loans granted by the ESM, the period of time for which we lend money to the beneficiary countries depends on its individual circumstances and ability to repay. But in general, our average loan maturities are longer than those of other lenders, such as the IMF. They range from 12.5 years in the case of Spain to 42.5 years for EFSF loans to Greece. This gives countries a breathing space to get back on the path of economic recovery and then slowly start paying back loans in small instalments over a longer time.

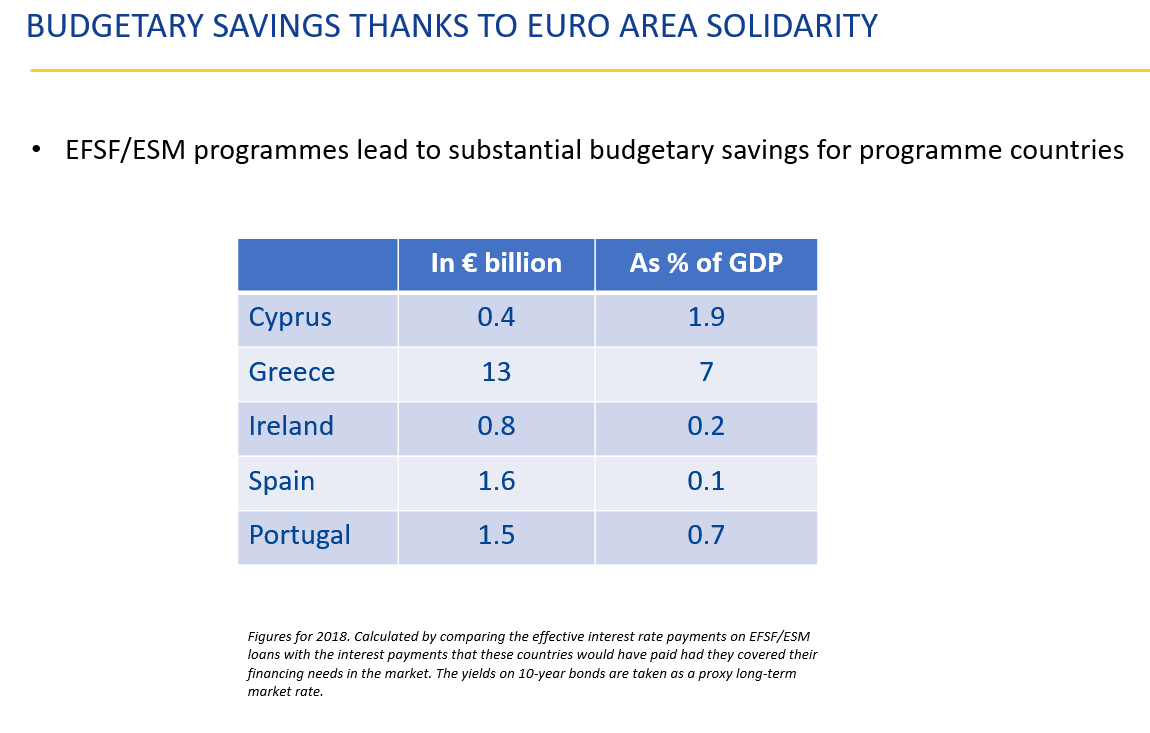

I mentioned that the ESM can borrow money at very low rates. These low rates are passed on to the beneficiary countries. Thus, the interest payments they make to the ESM are well below what the countries would be charged by investors. In the case of Greece, this saved the country’s budget €13 billion in 2018, or 7% of GDP. These are very substantial amounts and can be seen as an expression of euro area solidarity with the countries that requested assistance. This is what I mentioned earlier in my lecture.

You may wonder who takes the decision to grant an ESM loan? What kind of procedures are used? The ESM is an intergovernmental institution. Each of the 19 euro area Member States is represented in the ESM Board of Governors – our highest decision-making body – by their minister of finance. The most important decisions, such as the approval of a new country programme are taken by mutual consent. This means that if even a single country objects, the other countries cannot force their will.

There is one exceptional situation when the mutual consent procedure would not apply. This would occur if both the European Commission and ECB conclude that failure to urgently adopt a decision to provide financial assistance would threaten the economic and financial stability of the euro area. In such a case, a decision could be made with at least 85% of the votes cast. However, this has never happened in the seven years of the ESM’s existence.

Strengthening the euro area

The creation of the rescue funds for the euro area – the temporary EFSF and the permanent ESM – was a key step in restoring financial stability during the euro crisis. As we explained, it gave five countries the time to implement necessary reforms that allowed them to achieve economic recovery and return to market financing.

In parallel, the EU introduced a number of measures to prevent the build-up of debt to dangerous levels from happening again. New procedures were established to avoid macroeconomic imbalances. Economic policy coordination was strengthened, with countries required to submit draft budgets to the Commission.

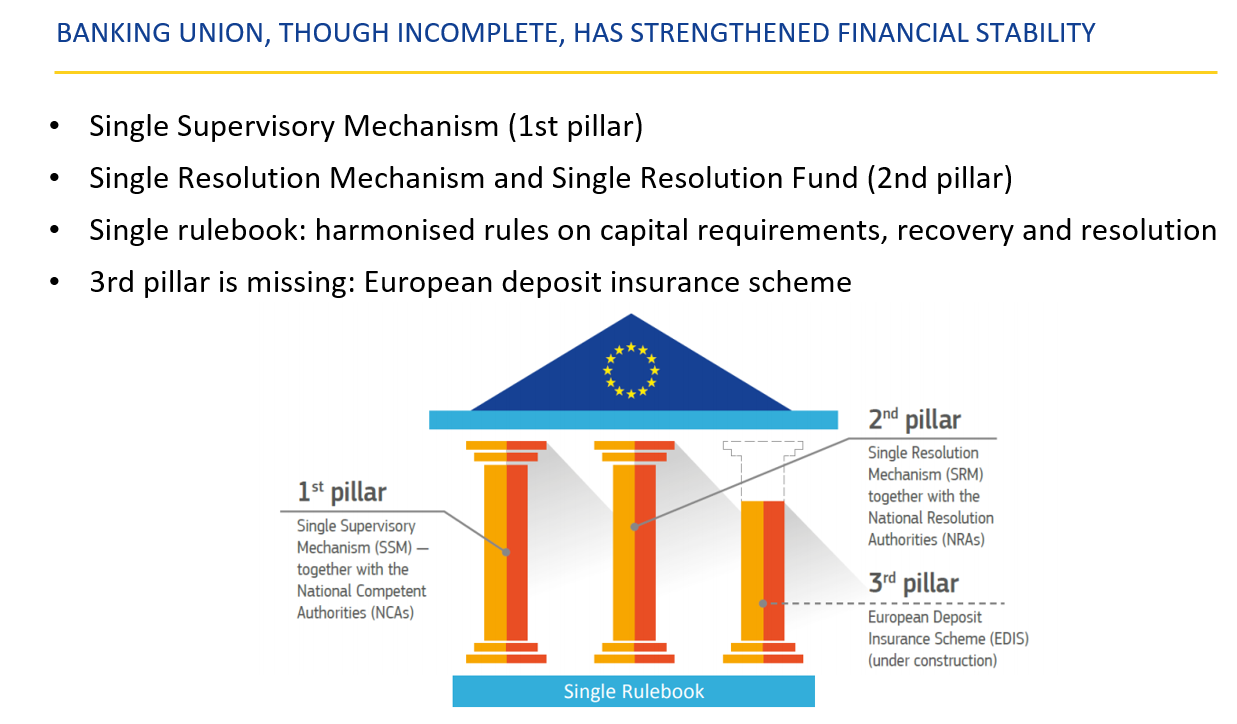

Furthermore, efforts were made to ensure a safer banking sector, as that was where some problems originated during the euro debt crisis. This led to the establishment of a banking union, which is illustrated on the slide.

The banking union currently consists of a supervisor for the euro area’s largest and systemic banks – the Single Supervisory Mechanism, which is institutionally part of the ECB. The second existing pillar is an authority responsible for bank resolution – that is restructuring failing banks in an orderly way. This is the Single Resolution Mechanism, which operates a fund for financing resolutions, the Single Resolution Fund (SRF).

There is a remaining pillar which is yet to be agreed at political level: a European deposit insurance scheme. Currently, deposit insurance is carried out at national level. This fact means that banks continue to be exposed to potential instability in their banking systems. The proposed European solution would address this problem, but as this would require a degree of risk-sharing among euro area countries, it will take some time to achieve progress.

ESM reform

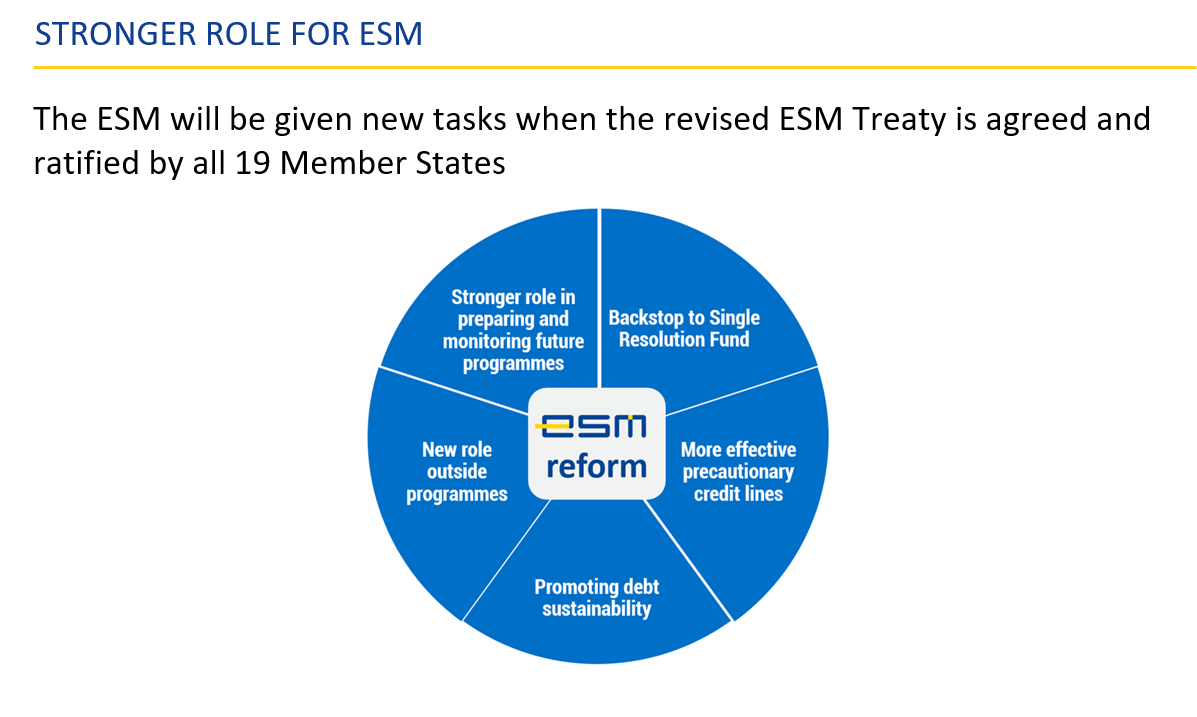

The euro area today is stronger and more resilient than it was ten years ago. However, there are a few remaining steps that need to be taken to ensure that it is capable of withstanding a new crisis if it occurs one day. Apart from the completion of banking union, this includes strengthening the role of the ESM. This has already been agreed by the euro area Member States, with a few final technical details to be finalised. What will be added to the ESM’s responsibilities?

First, we will provide the backstop to the Single Resolution Fund. In the event that the resources of the SRF are not sufficient, the ESM will be able to lend the necessary funds to the SRF to finance a resolution.

Furthermore, the ESM will play a stronger role in future economic adjustment programmes. In collaboration with the European Commission, the ESM will design, negotiate and monitor future assistance programmes. Outside programmes, the ESM will closely follow developments in all 19 euro area countries.

In addition, one of our lending tools – precautionary credit lines – will be made more effective thanks to a more transparent eligibility process to protect countries that could be drawn into trouble through contagion.

These new tasks are included in a revised draft of the ESM Treaty. The revised Treaty will come into force when it has been ratified by parliaments in all 19 ESM Member States.

Conclusion

It is natural that in a monetary union we strive for unity: a common currency requires a high level of policy coordination, with common rules and institutions. On the other hand, Europe is a union that consists of different cultures, different economic structures and different political traditions. This can be a challenge sometimes, but at the end of the day, these differences complement each other. This became clear during the crisis, when European solidarity was very evident: all euro area countries worked hard to keep the monetary union together.

And it was thanks to the commitment of our countries to safeguard the common currency, and preserve the integrity of the euro area, that the ESM was created. With our emergency loans, and the reforms implemented by the programme countries, we were successful. We can continue to enjoy the benefits of our common currency, which was not so obvious a few years ago.

In the foreseeable future, the ESM will not be as visible as it was during the euro crisis, because I do not expect us to have five programme countries again. We will be working very hard to prevent any crisis and be prepared if it actually occurs. You can be assured that the ESM will be ready to come into action if needed, like a fire brigade. The financial stability of the euro area is in safe hands with the ESM, both in crisis times and in normal times – as we are experiencing now. We will be working every day to make sure that the five beneficiary countries are on the right track to maintaining sustainable economic growth. And we will be following economic and financial sector developments in all the other euro area countries jointly with our colleagues in the EU institutions so that we know immediately if the first signs of problems appear. Whatever the circumstances, the ESM will be a crucial part of the euro area’s financial safety net.

Thank you very much for your attention.

Author

Contacts