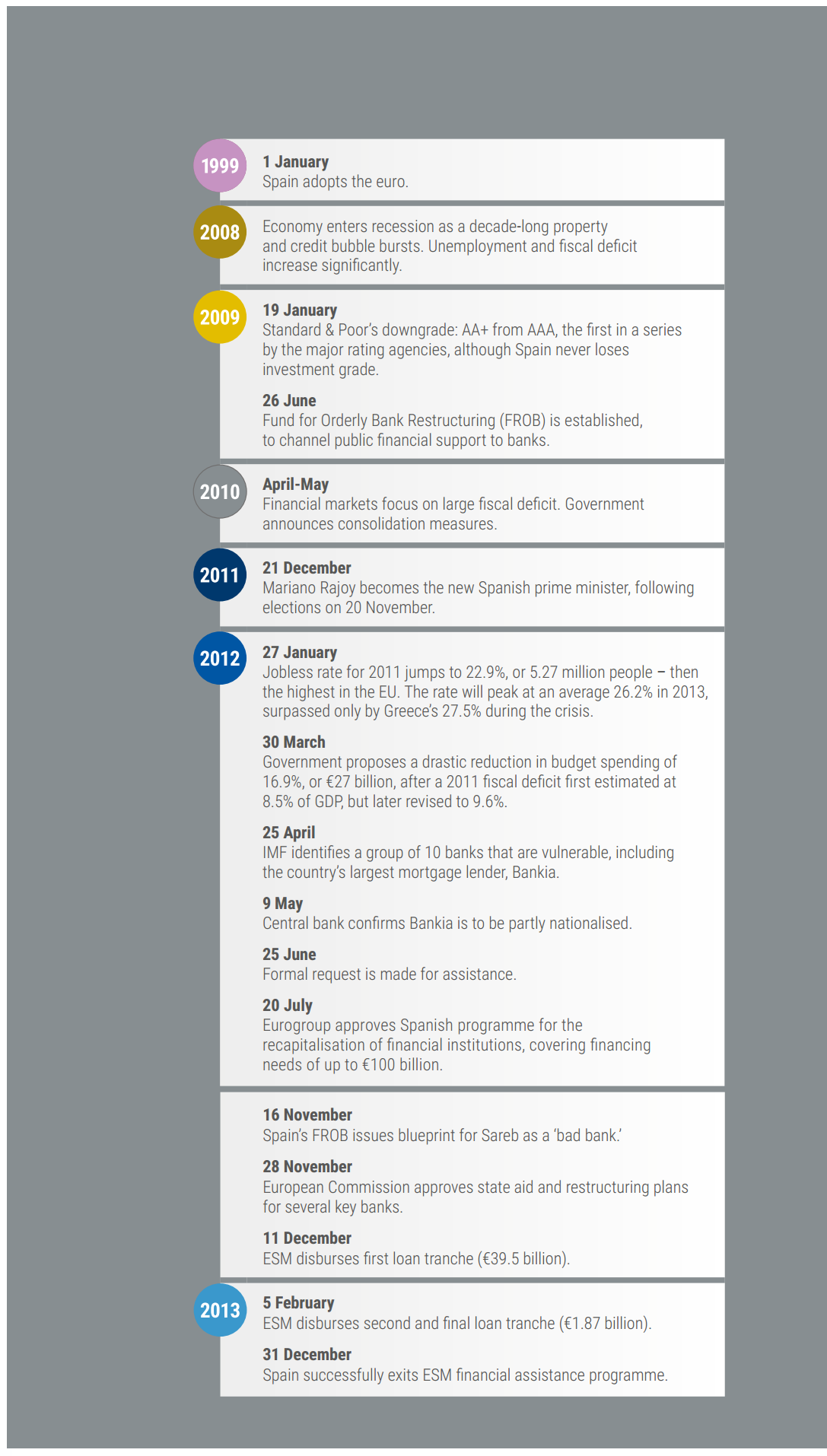

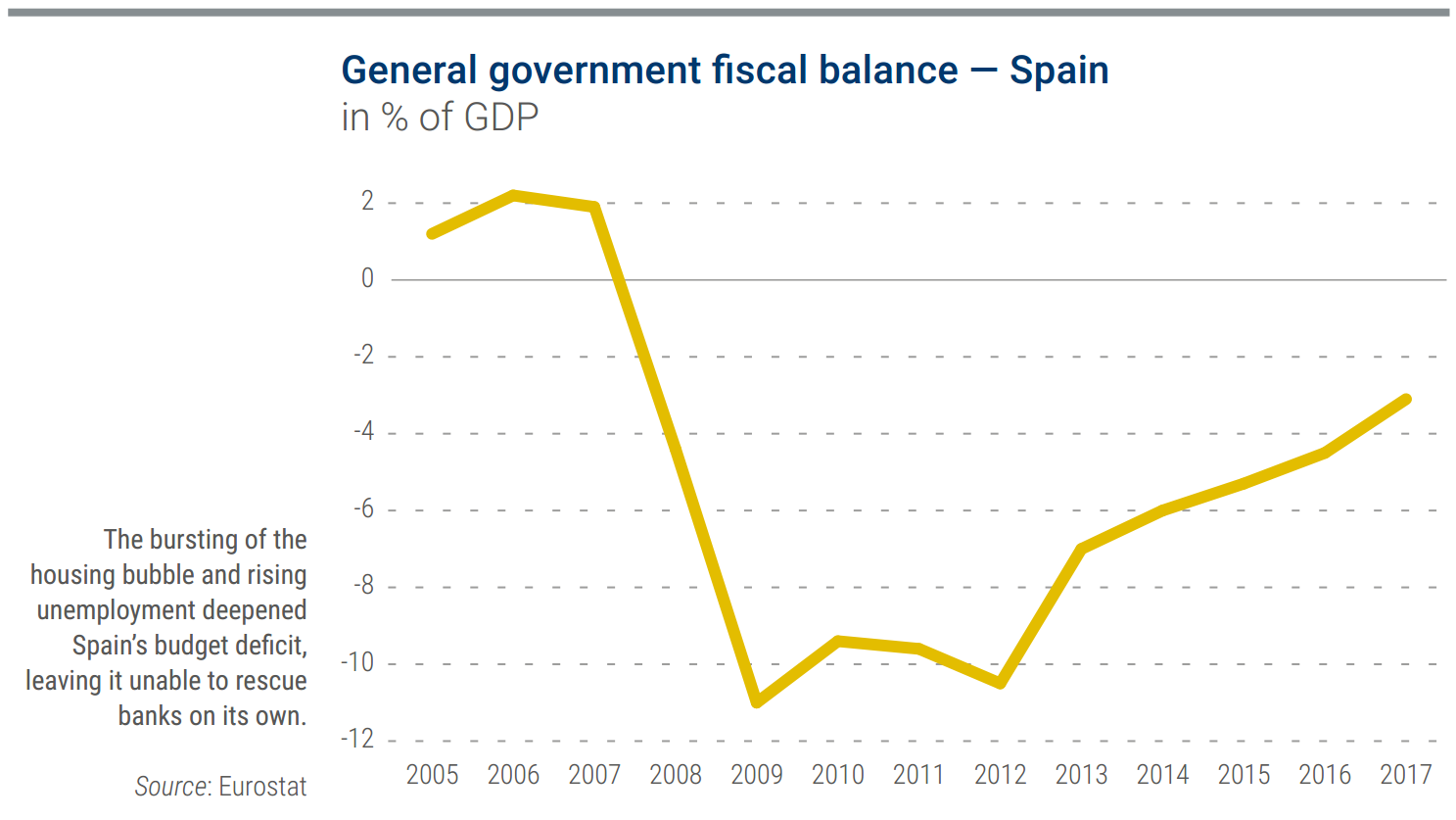

Spain’s crisis was a boom-bust cycle turned explosive by euro area contagion. In the 2000s, the Spanish economy was generally flourishing, its growth outpaced its European neighbours, and the budget recorded a solid surplus in many years. Most job seekers could find work, aided by a construction boom. Easy loans from banks fed a bubble, as house prices nearly tripled between 1997 and 2008.

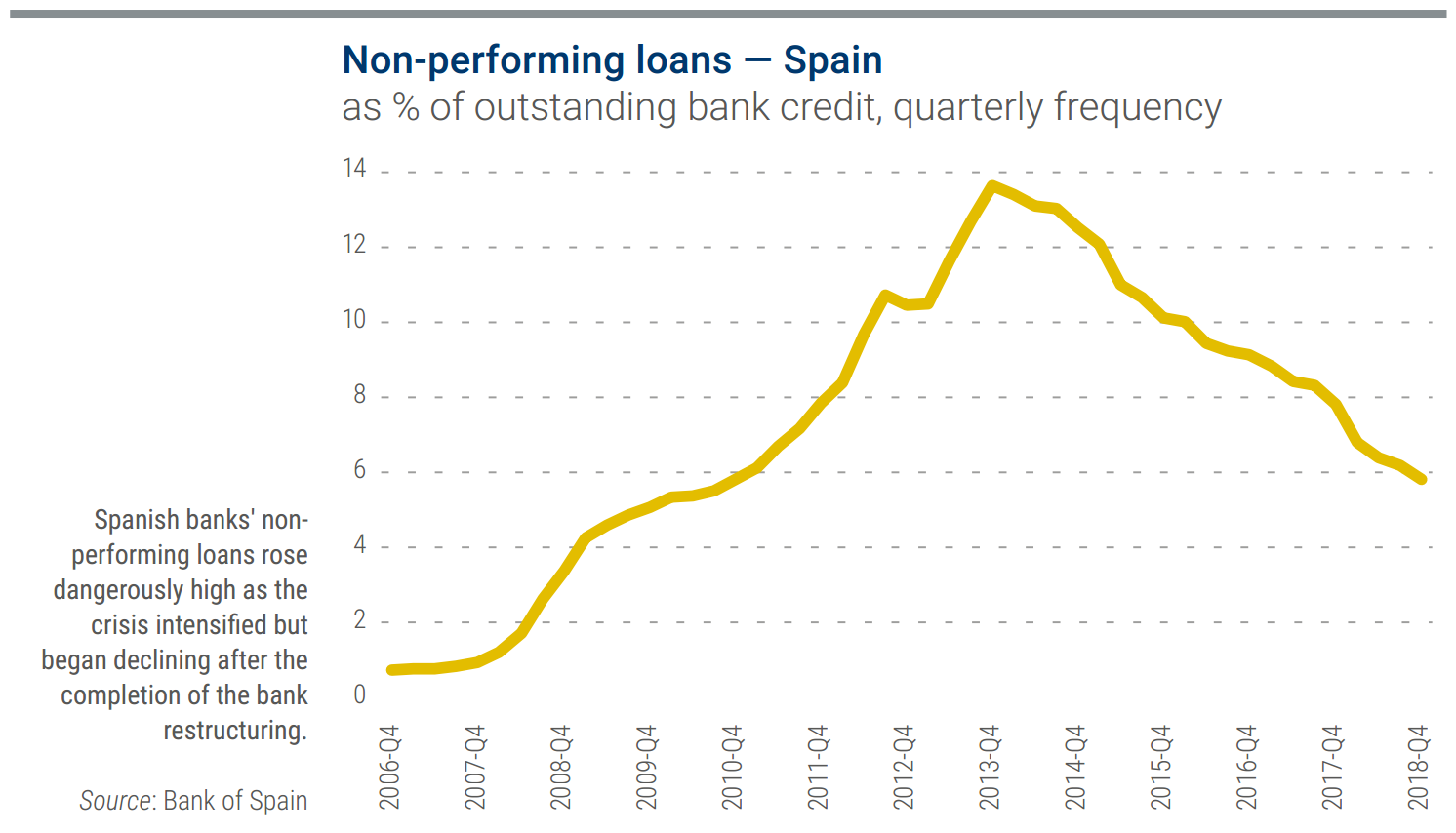

When the credit crunch hit, real estate prices collapsed. Clients, particularly real estate and construction companies, struggled to repay loans and banks were left with huge losses.

By 2009, Spain was in recession. As the economy contracted, high unemployment and debt levels added to the real estate woes. Growth improved a little in 2011, but, by the end of that year, almost one in four Spanish workers couldn’t find a job. Spain was home to the highest unemployment in the EU that year. The rate kept rising, peaking in 2013 at an annual average of 26.2%, or six million unemployed. By then, Greece had taken over as the country with the bloc’s worst-performing labour market, with a jobless rate of 27.7%[1].

‘Spain faced the combination of a loss of competitiveness, a credit bubble, and a housing bubble. After the outbreak of the international financial crisis, these imbalances led Spain into a triple crisis: banking, fiscal, and labour,’ said Luis de Guindos, who joined Rajoy’s government as economy minister after elections in late 2011.

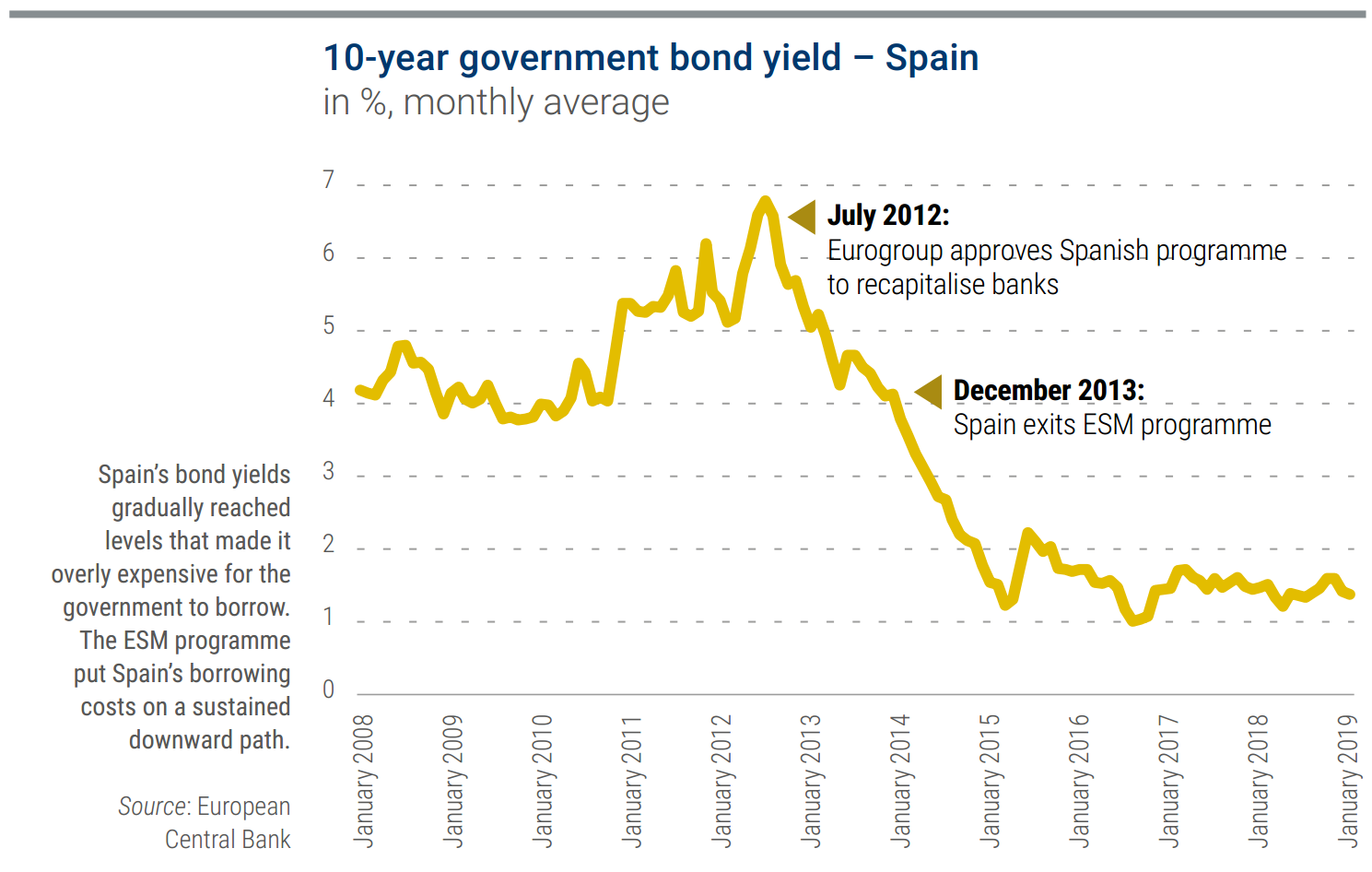

As Spain fell back into recession at the start of 2012, the euro area threatened to disintegrate around it. Greece was still struggling. Ireland’s and Portugal’s government bond prices had fallen and yields soared in the summer of 2011. Both countries faced downgrades from the various rating agencies, and other countries confronted market strain as well.

Spain was under enormous pressure to get its finances under control quickly. De Guindos said the rest of the euro area began to see Spain as a concern, encapsulated by a chance encounter at a gathering of finance ministers.

‘The story I remember best, largely because of its media impact, was a practical joke that Jean-Claude Juncker – who then chaired the Eurogroup – played on me in March 2012,’ de Guindos said. ‘Juncker approached me, without my seeing him, at the start of a Eurogroup when the cameras were still in the room. He put both hands around my neck, pretending to strangle me.’ De Guindos continued: ‘First I was shocked, but I quickly understood it was a joke, laughed, and the grip ended in a hug. The image appeared everywhere in the media because it symbolised perfectly the situation we were in. Europe did not trust Spain after the deficit mushroomed, and wanted to tighten the screws on us to ensure that we reduced it at a faster pace than we could manage.’

Spain passed a budget law that enacted big cuts of nearly 16.9%, or €27 billion, in March, as it attempted to rein in a public deficit that was first put at 8.5% of GDP in 2011 and later revised to 9.6%[2]. But the banking problems would prove too difficult for Spain to resolve on its own. In April 2012, the IMF said the past four years had seen ‘a crisis of unprecedented proportion in the Spanish financial sector’[3].

With further pummelling from global shocks, the banking crisis now threatened the entire Spanish economy. Even though Spain’s biggest banks were deemed well capitalised, the IMF warned that a group of 10 struggling lenders could topple financial stability if not addressed. Furthermore, in its June 2012 financial stability assessment report on Spain, the IMF’s team pointed to vulnerabilities, with ‘the risk of an even more severe downside shock than embodied in the analysis’[4].

Banks were not doing enough to make sure their clients could pay back their loans. At the time, banks – not just in Spain but also in many European countries – did not report the amount of underperforming loans in their financial reports, which undermined market confidence in the banks’ stated health. Right before the IMF report, several Spanish banks faced credit-rating downgrades, some reaching junk status, and Spain’s previous repair efforts began to fall apart.

‘Despite the reform marathon, I realised that we were going to have to ask for help when we began to see, in the first days of May 2012, the real situation of the banks and, in particular, of Bankia, which had to be nationalised,’ de Guindos said.

Bankia had been founded in 2010 from a group of seven struggling savings banks to become Spain’s largest real estate lender and, overall, one of the largest banks in the country. When it had to be completely taken over by the state, the Spanish government’s stake was converted to voting equity. Bankia also became a test case for the way bank bondholders were treated across Europe. Under EU rules, for Spain to be allowed to pump more aid into the bank, it would need to figure out how bank bondholders would help share the burden.

Confidence was faltering. Some €300 billion in foreign capital fled the country over the year from the third quarter of 2011 to the third quarter of 2012, largely as a drain on the balance sheets of the financial sector. Spain needed to win back market credibility – and fast.

Spain’s access to markets had become more limited, with the risk that it wouldn’t be able to borrow enough on its own, de Guindos said. ‘We needed a solution that would prevent the damage that the housing and credit bubble had caused financial institutions from affecting the public treasury.’

Cristóbal Montoro, the Treasury minister, laid bare the situation on 5 June: ‘The risk premium says Spain doesn’t have the market door open. The risk premium says that as a state we have a problem in accessing markets, when we need to refinance our debt’[5]. Four days later, the Eurogroup indicated it would respond favourably to a formal request for assistance.

Despite the Spanish government’s efforts to cut the budget and rein in the banks, more was needed. ‘Before requesting assistance, Spain tried to solve the problem by consensus,’ said Juan Rojas, a former Bank of Spain economist who now heads the ESM’s economic and market analysis team. ‘They tried to change several laws to make the banking sector more resilient, but the uncertainty regarding the quantity of bad loans in the banking sector was so huge that the market did not believe in the process. That is why, in the end, Spain had to come to the ESM.’

On 25 June, Spain requested a programme for its banks[6]. The yield on Spain’s 10-year government bond averaged a painful 6.6% that month, an expensive rate at which euro area sovereigns typically no longer issue. Cyprus requested a programme on the same day, although its programme would take much longer to negotiate and would include a full macroeconomic assistance package.

Spain was the first, and so far the only, euro area member state to request a rescue programme only for the financial sector. One of the euro area’s largest economies, it didn’t require a full macroeconomic adjustment programme because of reforms implemented earlier and because it was still able to borrow on capital markets. By limiting the aid programme to the financial sector, Spain could focus on ‘the root of the problem,’ Rojas said.

Euro area leaders reacted positively. On 29 June, they urged rapid completion of the aid deal. And on 20 July the Eurogroup approved it and bond yields started to drop. The Eurogroup granted Spain a financing envelope of up to €100 billion, although the precise amount would be determined after a more detailed assessment of the banks’ capital needs[7]. Three days later, the EFSF Board of Directors approved the assistance. The EFSF was fully prepared to act and pre-funded €30 billion in notes that could have been deployed if needed, although the money was never used in the interim period between Spain’s request and the start of the ESM.

As Spain prepared for the ESM programme, the capital outflows came to an end[8]. ‘I must underscore that, although markets, some of the press, and foreign and Spanish businesses pushed us to ask for a full programme, this was never on the table,’ de Guindos said. ‘As doubts were highly concentrated in the financial sector, it was best to tackle the fire with a programme limited to banking.’

Its financial adjustment programme was intended solely for indirect bank recapitalisation, meaning the ESM would lend to the Spanish government for the sole purpose of restructuring the banking sector. Nonetheless, the Spanish knew they would need to assuage markets by having access to enough money to quash any doubts. ‘In previous negotiations, it had become obvious that we had to ask for a sufficiently excessive amount to send the message that, no matter how big the problem, we were covered,’ de Guindos said.

From a technical standpoint, Spain had initially signed a deal with the EFSF because, at the time, the ESM was not expected to begin operations in October. The ESM took over the programme in November 2012, just before Spain negotiated its first instalment. That made Spain the first client of the permanent firewall. The role of the IMF had to be limited, as it does not provide any loans to specific sectors such as banking. Instead, the IMF took part in an advisory capacity, without offering Spain any money. Or as IMF chief Lagarde said: ‘We participated in Spain but as a monitor.’

Before euro area bank supervision began in 2014 and the Single Supervisory Mechanism began conducting regular comprehensive assessments of the big banks that came under its care, European authorities were reviewing the Spanish financial sector to determine the level of need. However, given market concerns about banks’ financial reporting, and the May 2012 partial nationalisation of Bankia, Spanish authorities thought they needed to take matters one step further in assuaging any fears about forthrightness.

‘At the time there was considerable speculation about the situation of Spanish banks, with erroneous figures floating about. These doubts could only be cleared up with a fully transparent exercise. So we commissioned an independent evaluation,’ de Guindos said.

Spain retained the consultancy firm Oliver Wyman to conduct an independent and comprehensive review of Spanish banks. In

September 2012, the report[9] identified a group of Spanish banks, including the mortgage-lending giant Bankia, that would need significant additional capital. In the short run, this contributed to another downgrade[10].

The Eurogroup tied Spain’s assistance to a set of conditions for the financial sector. Under the programme, Spain would improve the way it regulated and supervised its banks, figure out a new approach to the bad loans clogging up balance sheets, and put together in-depth bank restructuring plans. The overhauls would be designed in cooperation with the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Competition, to make sure they were in line with EU state aid rules.

Spain attempted to anticipate the rescue programme’s conditions by pledging to meet its EU-set budget goals and by amending its banking laws to match the euro area requirements. De Guindos said the main accomplishments were ‘making the savings banks – which had been in trouble for some time – disappear and improving corporate governance,’ along with creating a Spanish bank recapitalisation fund. Set up in 2009, the Fund for Orderly Bank Restructuring, commonly known as the FROB from its Spanish acronym, would make the resolution process for Spanish banks more uniform and transparent[11].

There was also a ‘bad bank’ tasked with taking troubled loans off bank balance sheets and pushing for repayments. Called Sareb, from its Spanish acronym, it is a private sector entity put together as part of Spain’s euro area aid programme. It received about 200,000 bad loans and foreclosed properties, totalling about €51 billion, from banks that had been nationalised and restructured as part of the programme[12].

Another potential difficulty emerged. Under treaty rules, the ESM enjoys preferred creditor treatment over other bondholders. While markets had accepted that Greece had to impose haircuts on its private sector bondholders, they were skittish about how quickly that precedent could extend to the rest of the euro area. In the case of Spain, they began to question if it meant the country’s overall credit risk was worse than the euro area was admitting to. This was the last thing Spain – which was not completely shut out of financial markets – needed.

As the financial assistance for Spain was originally to be provided by the EFSF, the Eurogroup decided that the ESM assistance programme would maintain the status of EFSF loans, whose debt was on an equal footing with that of other creditors, rather than follow the preferred creditor status of ESM loans[13].

The FROB also would have to decide which bank creditors should share the burden of recapitalising the banks, one of the conditions set out by the rescue agreement. This was controversial both because of the lack of precedent and because of the way bank debt had become embedded in the overall economy. Ordinary households had sunk their savings into bank bonds that were far riskier than promised, and one of the FROB’s challenges would be figuring out how to protect these individuals while also treating all creditors fairly in the writedown process. In the end, the FROB chose to impose losses on junior creditors while protecting senior creditors, and it later carried out a domestic programme to compensate ordinary households that had lost savings in the process.

To keep the banks safely open and avoid a run on the banks, almost all of the necessary recapitalisation funds from the ESM were disbursed in one go. This required some creative thinking from the funding team, which resorted to a cashless system of floating rate notes and zero coupon bills.

Technical procedures surrounding programme implementation gave some reassurance that Spain would stay on a solid footing even after the disbursements, ESM Chief Economist Strauch said. For example, the Commission required Spain to show its business plan for the sector before financial assistance could be released. The Commission approved the state aid plan on 28 November[14], allowing the first disbursement of just over €39 billion to go forward less than two weeks later in December 2012, followed by a second, far smaller, disbursement in February 2013[15].

‘Only then, once everything is cleared and the European Commission’s decision is taken, do we ship any type of capital, which is much sounder and has now become the general approach,’ Strauch said. ‘Overall, this was skilfully handled, on the Spanish side and from an overall programme management perspective.’

In the end, Spain used only around €41 billion for the banking sector out of the total potential €100 billion. The rescue programme was a true firewall, giving Spain the time and security to put its economy back on track. ‘We believed that with the rescue of the banks in general, and of Bankia in particular, the situation would improve, and that was indeed the case,’ de Guindos said.

In de Guindos’ view, although contagion was real, markets over- reacted to Spain’s difficulties. They were uncertain about the solvency of the financial system and how this would affect sovereign debt, meaning Spain was seen as a bellwether for the entire common currency. ‘In part, the markets attacked the euro through Spain, because they perceived it as the weak link and, in part, because their view of our economy was worse than reality,’ de Guindos said.

Spain’s programme was short – only 18 months. It probably helped that it was more focused than the other programmes.

After Spain exited its programme in December 2013, the reforms undertaken helped spark a surge in economic growth.

‘The restructuring of the financial sector also interacted with other reforms, such as labour, energy, the single market, budgetary stability, and trade liberalisation. This, together with efforts to reduce the deficit, is what is driving Spanish growth – currently at twice the euro zone average,’ de Guindos said in 2016.

Spain underlined this better performance by voluntarily starting to repay its ESM loans in 2014, earlier than required. By October 2018, it had made nine voluntary repayments, paying off 42.6% of the total outstanding amount of the €41.3 billion ESM loan to Spain and leaving it at €23.69 billion.

In its 2017 review of the Spanish economy, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development said: ‘The Spanish economy is enjoying a robust recovery from a deep recession, with structural reforms contributing to high growth rates and a gradual decline in unemployment.’ It added that ‘further measures are needed to boost productivity and to ensure that the benefits of growth reach all Spaniards’[16].

Focus

When bonds are better than cash

When the firewall provides countries with financial aid to recapitalise their banks, it puts a different kind of financing strain on the ESM from regular rescue loans. To keep banks open and avoid a bank run, bank recapitalisation – whether through a bank-only programme such as Spain’s, or as part of a wider programme as was the case for Greece and Cyprus – often needs to happen all at once. But, as anyone who has needed to raise cash in a hurry knows, market interest rates can sometimes be punitive.

An EFSF and ESM innovation to get around this was to use floating rate notes instead of cash for the disbursement of the loan. Those bonds, which have a variable interest rate, are sold to one of the 40-odd international banks that belong to the ESM Market Group, in a process needed to legally create the notes, and then the ESM immediately repurchases the notes after the bank subscribes. No gains or losses are linked to either transaction, both of which occur on the same day and for the same price. The ESM then holds the notes until the programme country requests a loan to inject capital into its banks, at which point the notes are transferred to the recipient banks to serve as capital.

Thus, this issue and repurchase programme creates notes by issuing securities and immediately buying them back. It means that the EFSF and ESM don’t have to overwhelm the market with a big short-term request for cash, said Strauch, who credits Head of Funding Ruhl with coming up with the idea together with CFO Frankel and an outside banking advisor. For the banks that receive aid, the attraction is having good-quality securities on their balance sheets.

Greece was an early test case for the floating rate notes, which the EFSF used to provide a €25 billion capital increase for the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund in April 2012, after Greece was granted its second euro area rescue package. Later, the notes were also used on a small scale in Cyprus under the ESM.

Spain, however, was where the issue and repurchase programme really proved its mettle. When Spain asked for its first disbursement in November 2012, the ESM had been in place for only a month. While legally sound, it was not yet an established issuer in the market – and it needed to find €40 billion in a hurry.

Had the ESM simply needed cash, it would have had to go to the market and take whatever money it could get at whatever price, Ruhl said. ‘This would have meant that we had ruined our reputation before we even began.’

But the Spanish banks weren’t looking for liquidity, they were looking for good-quality assets to hold as capital. This left the door open for a technical solution that gave the banks exactly what they needed and preserved the ESM’s market flexibility.

‘Instead of sending €40 billion in cash we sent €40 billion in bonds,’ Ruhl said. ‘We didn’t have to go to the market, we didn’t have to offer supply to the market. It meant we protected our existing curve. We protected existing investors. We weren’t forcing our existing bonds to cheapen because we weren’t flooding the market.’

Sending notes instead of cash essentially buys time for the ESM to accumulate funds. It’s a way of delivering support immediately without disrupting the market. The notes have different maturities with sufficient time in between so that the ESM has plenty of time to raise money in the markets to pay off the next maturity. For Spain, the total amount was split into the following six notes:

Details of the notes provided by ESM - Spain

Note: FRN, floating rate note; ISIN, International Securities Identification Number. Source: ESM

| ISIN | Issuance date | Maturity | Type | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU000A1U98X6 | 01/02/2013 | 05/08/2015 | 30-month FRN | €1.865 billion |

| EU000A1U97C2 | 05/12/2012 | 11/02/2013 | 2-month bill | €2.5 billion |

| EU000A1U97D0 | 05/12/2012 | 11/10/2013 | 10-month bill | €6.468 billion |

| EU000A1U98U2 | 05/12/2012 | 11/06/2014 | 18-month FRN | €6.5 billion |

| EU000A1U98V0 | 05/12/2012 | 11/12/2014 | 2-year FRN | €12 billion |

| EU000A1U98W8 | 05/12/2012 | 11/12/2015 | 3-year FRN | €12 billion |

‘This was no easy task,’ Ruhl said, and yet it was the best way forward. ‘Issuing to the market would have been extremely risky. We didn’t know how many investors were prepared to buy the ESM bonds. In addition, it was the second half of November – the market was calming down, we were coming close to year end, books were closed, nobody wanted to enter into new risks. This was the worst period of the year to raise a huge amount of money, and this with an issuer who hadn’t done any transactions in the market.’

To manage the process of creating and transferring the bonds as needed, the team created a variation of the approach used for the private sector involvement used in Greece. All worked well in the end.

Generally speaking, the ESM links the interest rate on the floating notes to the corresponding Euro Interbank Offered Rate, the daily reference interest rate known as Euribor. This rate moves in line with market conditions, meaning it can sometimes enter negative territory. The ESM later adjusted its approach to formally and explicitly set the interest rate floor for the notes at zero.

Continue reading

[1] Eurostat (n.d.), ‘Employment and unemployment (Labour force survey)’. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/lfs/data/database

[2] Spain, Prime Minister’s Office (2012) ‘El Gobierno aprueba el Projecto de Ley de Presupuestos para 2012’ (Government approves the 2012 Budget bill (ESM translation)), 30 March 2012. http://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/consejodeministros/resumenes/Paginas/2012/300312-consejo.aspx; Reuters (2012), ‘Spain reveals deep cuts to meet deficit goal’, 1 April 2012. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-spain-cuts/spain-reveals-deep-cuts-to-meet-deficit-goal-idUKBRE82T0OD20120401

[3] IMF (2012), ‘Spain: financial sector assessment, preliminary conclusions by the staff of the International Monetary Fund’, Online statement, 25 April 2012. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/28/04/52/mcs042512

[4] IMF (2012), ‘Spain: Financial stability assessment’, IMF country report No. 12/137, June 2012. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2012/cr12137.pdf#page=7

[5] Reuters (2012), ‘Spain says markets closing on it, seeks help for banks’, 5 June 2012. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eurozone-idUSBRE8530RL20120605

[6] Spain, Prime Minister’s Office (2012), ‘Spain formally requests financial aid for Spanish banks’, 25 June 2012. http://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/lang/en/gobierno/news/Paginas/2012/20120625_RequestAidBanks.aspx

[7] Statement by the Eurogroup, 20 July 2012. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/131914.pdf

[8] The Telegraph (2012), ‘IMF fears “credit shock” in Spain if Rajoy blocks rescue’, 10 October 2012. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financialcrisis/9600476/IMF-fears-credit-shock-in-Spain-if-Rajoy-blocks-rescue.html

[9] Oliver Wyman (2012), ‘Asset quality review and bottom-up stress test exercise’, Report, Madrid, Oliver Wyman, 28 September 2012. https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/SSICOM/20120928/informe_ow280912e.pdf;

[10] Spain, Prime Minister’s Office (2012), ‘Oliver Wyman estimates the Spanish banking system’s capital needs at close to €60 billion’, 28 September 2012. http://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/lang/en/gobierno/news/Paginas/2012/20120928_Spanishbanking.aspx; Spain, Central Bank of Spain (2012), ‘Cost of the Spanish banking sector solvency tests’, Press release, 31 October 2012. https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/GAP/Secciones/SalaPrensa/NotasInformativas/12/Arc/Fic/presbe2012_48e.pdf;Spain, Prime Minister’s Office (2012), ‘Oliver Wyman estimates the Spanish banking system’s capital needs at close to €60 billion’, 28 September 2012. http://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/lang/en/gobierno/news/Paginas/2012/20120928_Spanishbanking.aspx

[11] Spain, Minister of Economy and Finance (2009), ‘Minister of Economy and Finance order issuing guarantee of the Central Government (Administración General del Estado) to secure obligations to the Fund for Ordered Banking Restructuring arising from issues of financial instruments, the arrangement of loan and credit transactions, and the execution of any other financing transactions by that fund, in accordance with the provisions of Royal Decree-Law 9/2009, of June 26, on bank restructuring and reinforcement of credit institutions’ own funds’, Partial transcript. http://www.frob.es/en/Documents/Extracto_orden_otorgamiento_Aval_FROB_prot_En.pdf

[12] Sareb (n.d.), ‘About us’. https://www.sareb.es/en_US/about-us

[13] ESM (2014), ‘Frequently asked questions on the European Stability Mechanism (ESM)’, Factsheet, 28 July 2014. https://www.esm.europa.eu/sites/default/files/faqontheesm.pdf

[14] European Commission (2012), ‘State aid: Commission approves restructuring plans of Spanish banks BFA/Bankia, NCG Banco, Catalunya Banc and Banco de Valencia’, Press release, 28 November 2012. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-12-1277_en.htm

[15] ESM (n.d.), ‘Financial assistance for the recapitalisation of the Spanish banking sector’. https://www.esm.europa.eu/assistance/spain

[16] OECD (2017), ‘Spain: maintain reform momentum to enhance economic recovery and boost inclusive growth’, Press release, 14 March 2017. http://www.oecd.org/newsroom/spain-maintain-reform-momentum-to-enhance-economic-recovery-and-boost-inclusive-growth.htm