13. The crisis spreads to Portugal: a second call for aid

With Ireland and Greece in programmes, Portugal drew the focus of market attention. Its bond yields were already at critical levels in the spring of 2010, and the question became: would Portugal be next?

Albuquerque, who would later become Portuguese finance minister, was at the time leading the issuing department of the country’s debt management office. From that post, she could see the crisis threatening to engulf Portugal’s shores.

‘When we talk about contagion, it is of course always the most fragile or the most vulnerable that cause the biggest concern. Portugal was clearly in that situation,’ she said.

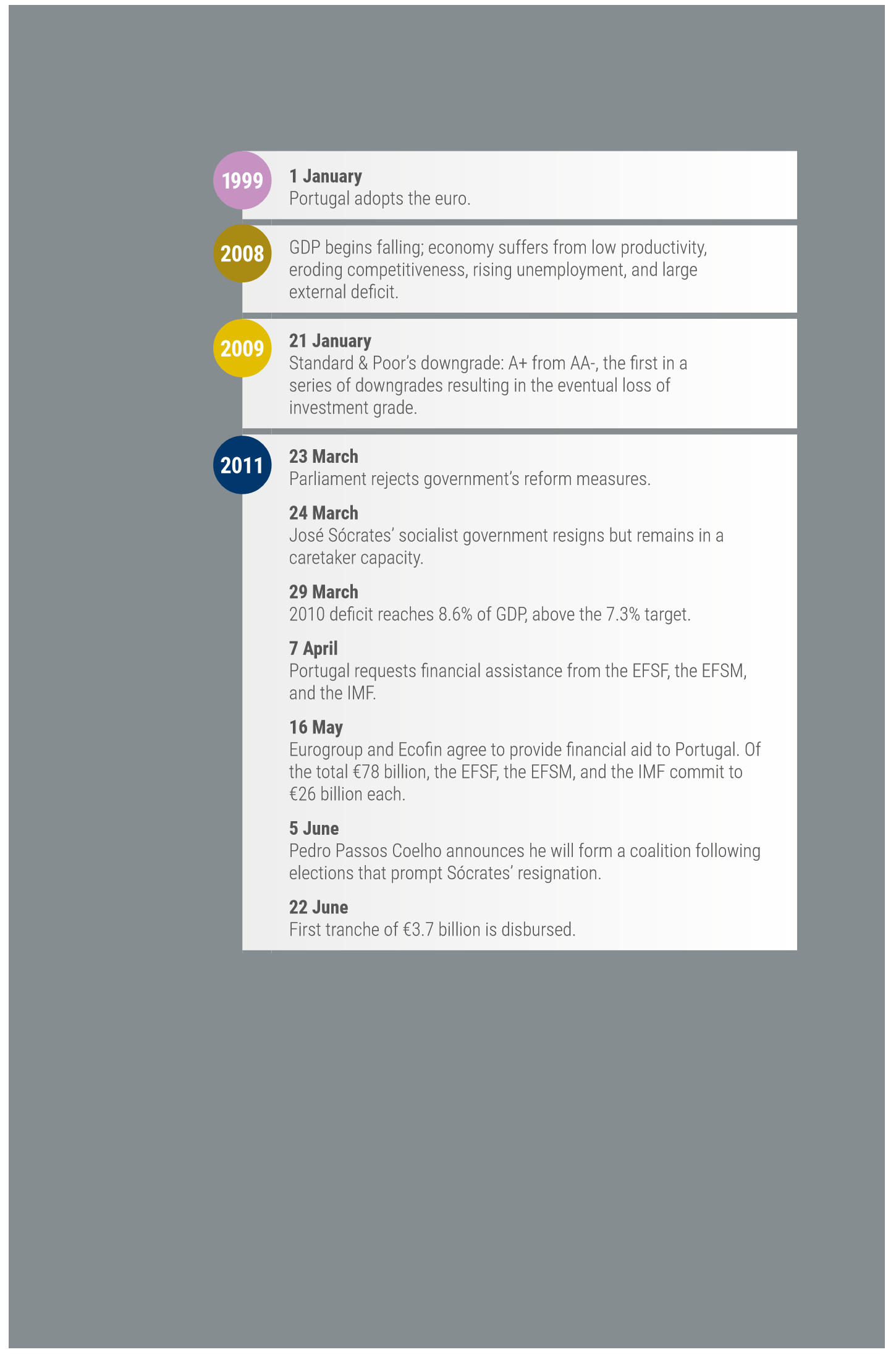

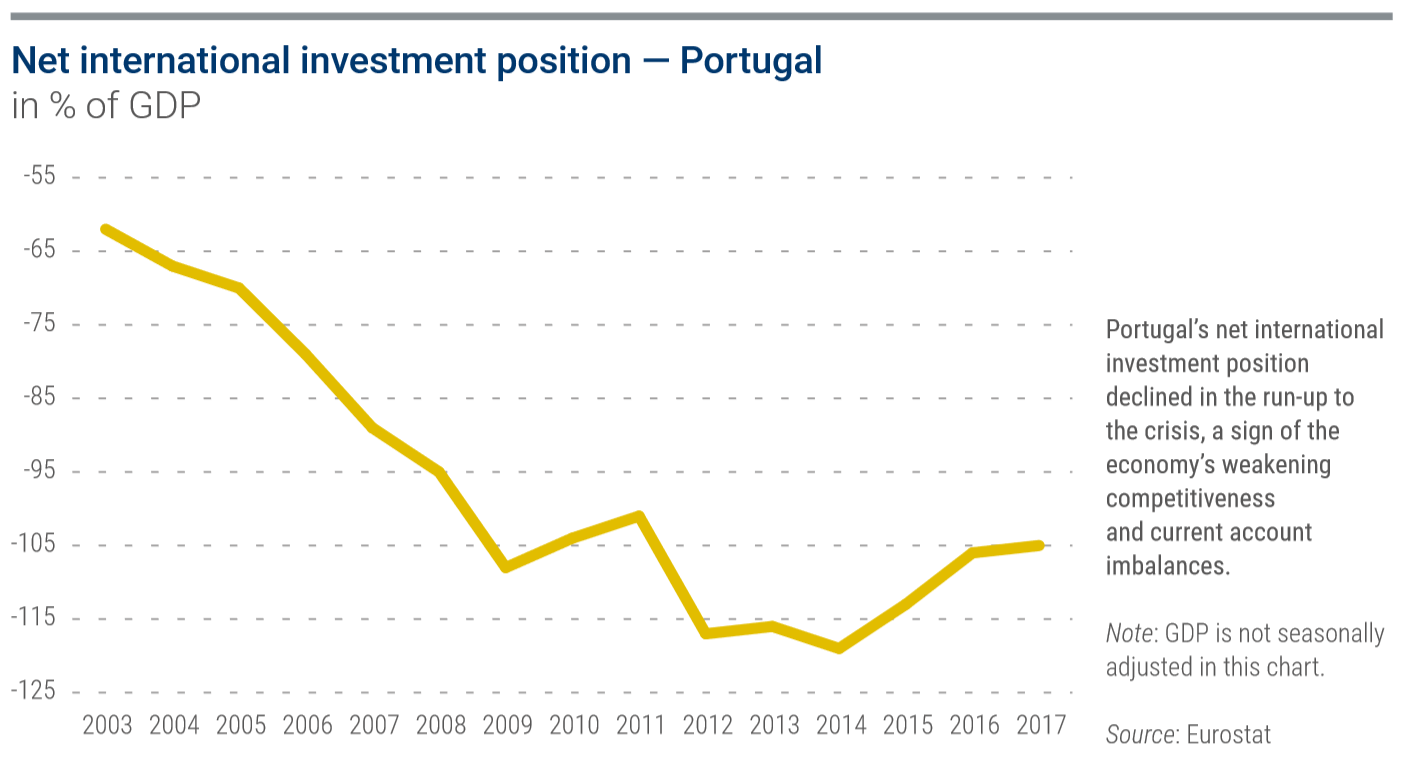

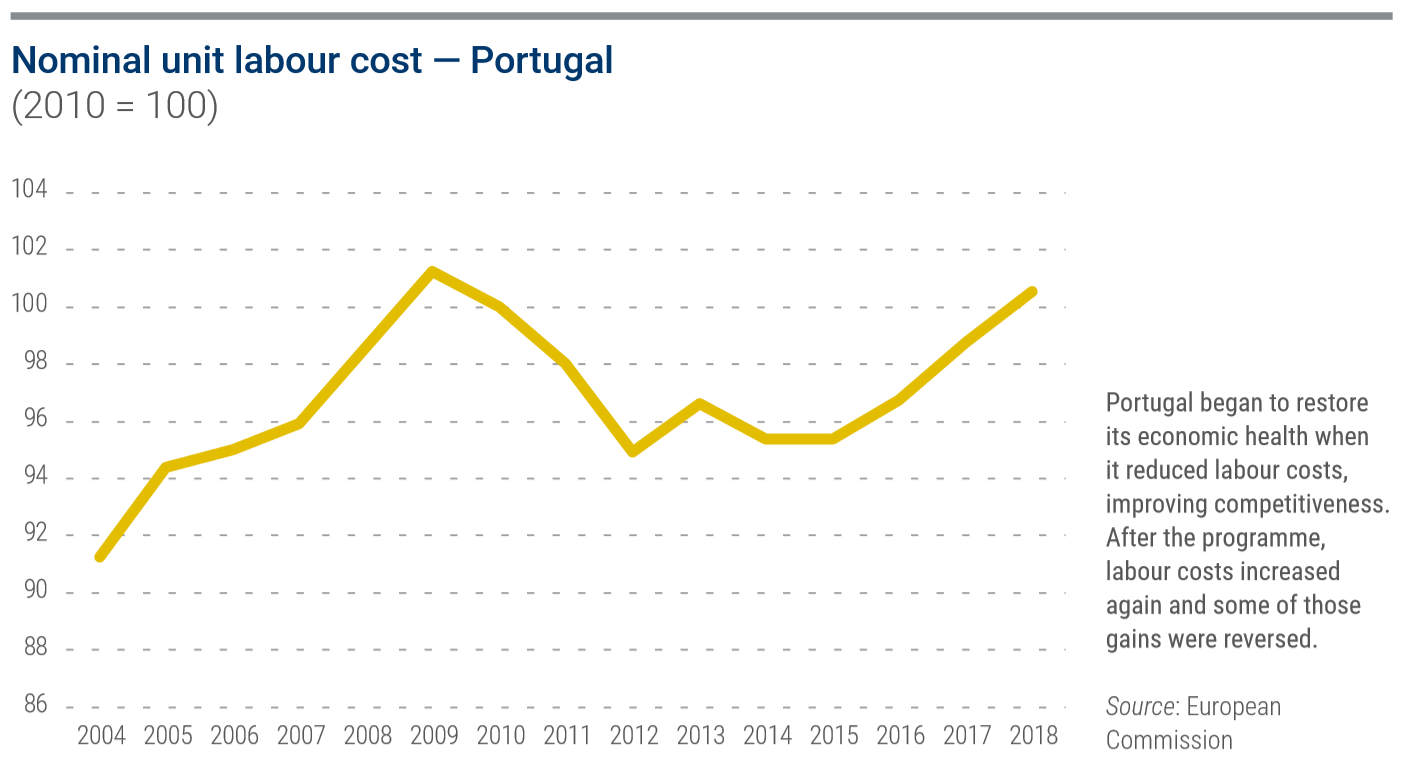

Portugal’s economy had been ailing for some time, with low GDP and productivity growth in the 10 years before the crisis[1]. Because of the low interest rate environment across the euro area following the adoption of the euro, credit had been easily available, contributing to rising debt levels for companies, households, and the government. With wage growth outpacing productivity gains, Portuguese products became more expensive abroad, contributing to a deceleration in export growth and a loss of competitiveness.

Banks were an additional weak link in the Portuguese chain. Investors worried that the Portuguese financial sector was overly exposed to the struggling economy, which in turn made the country even more susceptible to economic shocks. As interbank lending dried up across the euro area, the Portuguese banks resorted to central bank financing. That strategy couldn’t last indefinitely.

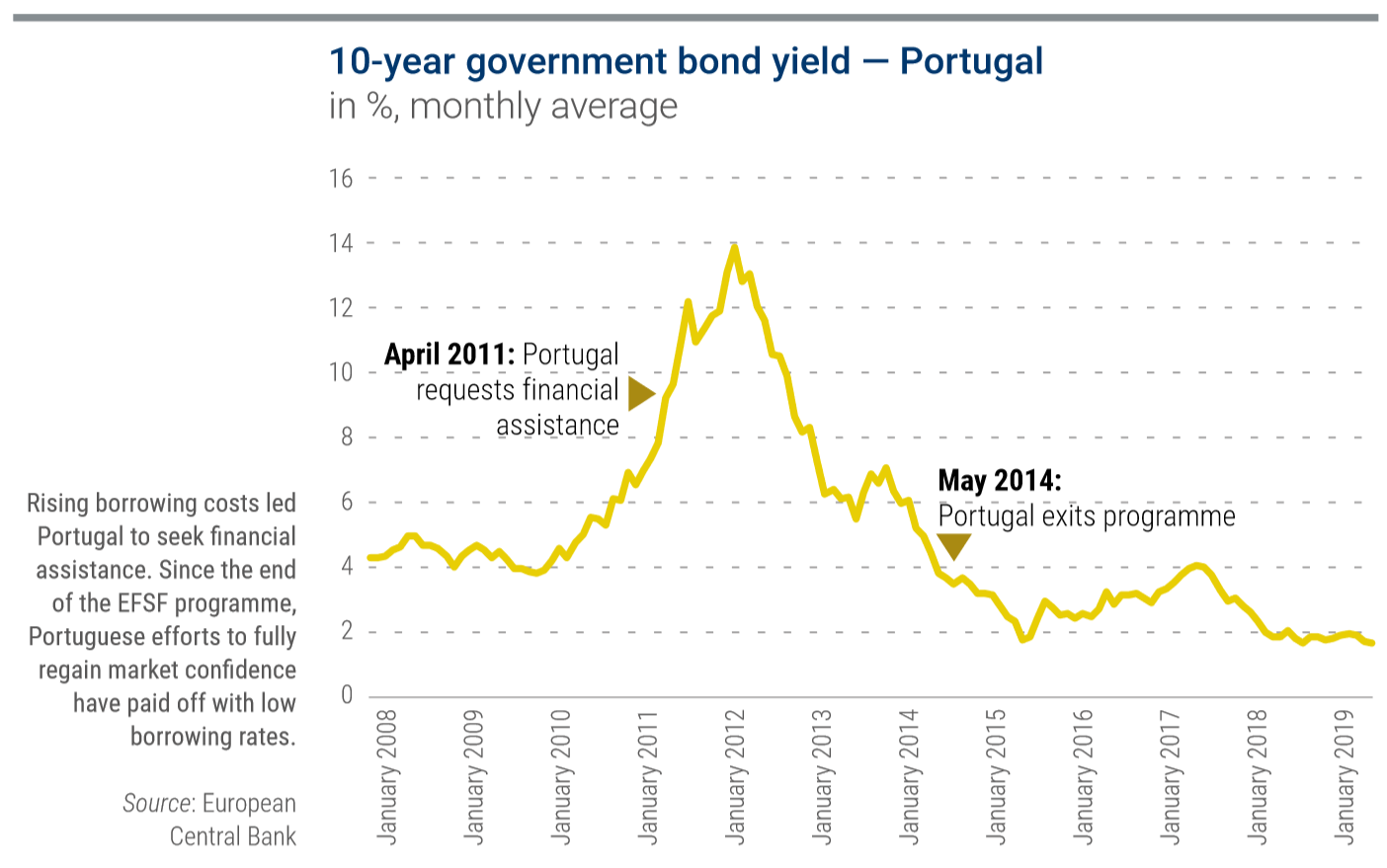

With a deficit that would, after multiple revisions, reach a record 11.2% of GDP in 2010[2], Portugal didn’t have much fiscal room to tide its economy over or respond to market pressure. As the budget news got worse, bond yields increased sharply from April 2010, hitting what the government perceived as critical levels as it rose above 10% by mid-2011.

‘The sense of urgency became clear,’ said Fernando Teixeira dos Santos, who was finance minister from 2005 to 2011.

Fitch had cut Portugal’s long-term debt to AA- from AA in late March 2010[3], the first in a series of downgrades resulting in the late 2011 loss of investment grade[4]. The successive cuts would spook markets further, leading to an even more rapid deterioration of the spreads. Yields on the 10-year bond would average 13.9% in January 2012, levels well beyond the point at which market access becomes unsustainable. Portugal’s domestic troubles had become caught up in the euro area’s broader spiral of contagion.

Still, authorities in Lisbon initially resisted asking for help. Gaspar, who served as Portuguese finance minister at a later stage of the crisis, said any country that might need international aid runs up against a ‘stigma effect’ in the eyes of the market. ‘There is definitely not an immediate boost to credibility associated with having a programme,’ he said.

Teixeira dos Santos said the IMF’s role in particular was an incentive not to seek aid, because of lingering resentment from two prior programmes in 1977 and 1983.

‘Policies were very restrictive. Recession, high unemployment, high inflation, declining real incomes, and a deterioration of living conditions at the time became associated with the IMF,’ he said. ‘Calling the IMF again would be like, for a child, calling for the “bogeyman”. Such memories implied it would impose a very high political cost. No wonder there was reluctance.’

This stance led to some tense moments in the Eurogroup’s Task Force on Coordinated Action, recalled Albuquerque: ‘I remember being in meetings where people said things like “we need to find a way of setting these programmes without stigmatising the countries involved because that leads to political resistance to admit that there are problems.” A roomful of people would look straight at me and someone would say “because there are countries that really need help but refuse to admit it.”’

In the end, it took a political crisis for the Portuguese programme to come together. José Sócrates’s Socialist government made a last effort in mid-March 2011 to win over the markets by pledging a deeper overhaul of the budget, with the support of the European Commission and the ECB[5]. But less than two weeks later, this reform package failed in the Portuguese parliament, prompting the minority government to resign and step into a caretaker role until after new elections[6].

By the end of March 2011, ‘it was not possible to go to the market for funds,’ said Albuquerque. ‘They were just too expensive and, from a certain point onwards, non-existent. It stops being a vague question of crisis. It becomes an immediate non-availability of the markets to lend.’

The deficit for the previous year was revised upwards to 8.6% of GDP, above the 7.3% target[7]. A few days later, at the start of April 2011, Portugal faced unsustainably high interest rates, with yields on the benchmark 10-year bond at 9%. Crunch time had arrived. On 7 April, the caretaker government asked for assistance from the EFSF, the IMF, and the Commission’s emergency fund, the EFSM.

‘The newly formed EFSF was keeping an eye on developments as it managed its own debut,’ said Chief Economist Strauch. As he remembers it, the process of encouraging Portugal to seek a programme evolved over time, until the outgoing government was forced to confront how tight market conditions had become. The start-up EFSF had only a small part in the preliminary discussions, he said. Its role ramped up once the programme was underway.

Portuguese politicians still trade accusations about the delay in asking for a programme. For Teixeira dos Santos, his government’s last-minute proposals were an effort to work with the institutions in a ‘precautionary way, to head off the need for a full aid programme and outside funds’, while also trying to bypass what he called ‘the stigma associated with seeking a bailout’. Albuquerque says the caretaker government was merely delaying the inevitable. ‘So it came late – it should have been done earlier.’

In 2017, the EFSF/ESM programme evaluation report concluded that an earlier request would have saved Portugal money. ‘Official requests for assistance came with considerable delay. Since countries must initiate requests for a financial assistance programme, such delays had financial and political consequences for the government,’ the report said[8].

At the same time, conditions in 2010 and 2011 discouraged early requests for help.

The EFSF was engineered so that programme countries would face high interest rates, just as Greece’s first, pre-EFSF rescue programme had come with high borrowing costs. The purpose was to avert the moral hazard of encouraging some countries to indulge in poor budget and debt management, thinking they could always resort to the firewall. These higher rates were revisited in 2011, but they were very much a part of the early design.

There was also a heavy political cost to seeking aid, and a worry that markets would attack any country viewed as entering the early phases of that discussion. As Teixeira dos Santos said, the perception in potential recipient countries is that ‘the stigma was and still is big.’

It took euro area countries over a month – until 16 May – to formally approve Portugal’s aid request[9]. In discussions at EU-level meetings, Albuquerque found feedback to be constructive but also tough. Portugal needed to own up to how things had got so bad and commit to repairing the situation, she said. Rebuilding credibility would be essential to keeping EU support.

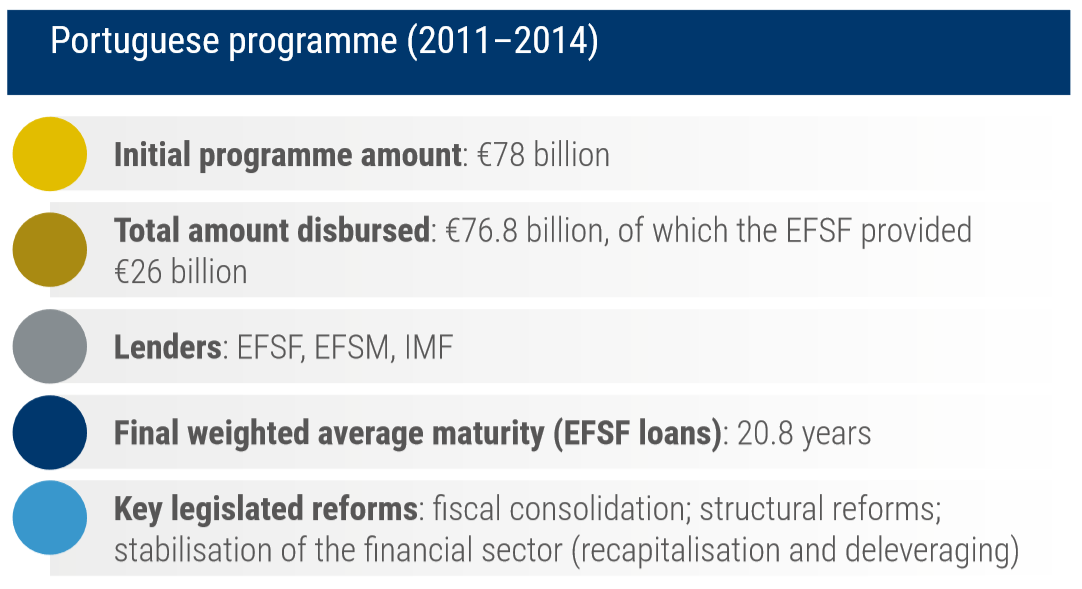

Portugal’s package – the second for the euro area’s new firewall – covered up to €78 billion in financing, split three ways between the EFSF, the EFSM, and the IMF. To get the programme underway, both the EFSF and the EFSM had to overhaul their financing calendars immediately, in order to raise the money for the initial disbursement within a matter of weeks.

The package allowed Portugal to pay its immediate bills and recapitalise its banks. In return, Portugal agreed to bring down its budget deficits, fix its banks, and modernise its economy. The IMF and EU institutions required stepped-up banking supervision and a front-loaded set of structural reforms designed to encourage growth and make the country more competitive. In particular, Portugal was called on to reduce unit labour costs, increase working hours in the public sector, make labour market rules more flexible, and update its housing and service sectors. The programme also sought judicial reform. Budget cuts were necessary, but Portuguese authorities were encouraged to head off possible public upset by designing tax increases and benefit cuts in a way that would minimise their impact on the lowest-income groups.

On 5 June 2011, the Socialist Party lost an election that delivered a big win to the Social Democratic Party. The coalition government of Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho embraced the economic rebuilding plan. Gaspar, the new government’s first finance chief, says the climate had defrosted considerably by his first meeting with other ministers from euro area countries in July 2011. ‘I was received quite warmly. At that point in time we had already presented our strategy for the implementation of the programme and that was very well received,’ Gaspar said.

It helped that public opinion in Portugal was in favour of the adjustment programme. ‘When the programme implementation started, the degree of consensus on the need for adjustment in Portugal was absolutely overwhelming,’ Gaspar said. ‘The parties that won the elections and formed the government had supported the earlier Socialist government in the process of the negotiation. During the campaign, they said clearly that they would, if elected, implement the programme in a committed and, they thought, successful way. And obviously the Socialist Party that had negotiated the programme campaigned on exactly the same broad approach. That led to a situation where, at the beginning of the programme, almost 90% of the parliament supported it.’

In the beginning, the euro area rescue fund focused more on Portugal’s funding needs than on whether or not it was fulfilling its programme conditions. Later in the programme, the firewall took a bigger role in technical talks. Albuquerque remembers the team as constructive and careful not to get in the way of its fellow institutions. ‘There was never a time, at least as it was reported to me, where the ESM raised an issue completely different from the European Commission,’ she said.

Strauch said Portugal showed early signs that it might have the political will to work through its difficulties. There was a spirit of optimism that the euro area was finding the right tools to navigate the crisis after the assistance programme for Ireland was agreed.

And, in contrast to the dreary weather of Ireland – where the deal was finalised on a snowy day in Dublin, in a basement room of the attorney general’s office with bars on the windows – the Portuguese sunshine gave a lift to morale.

‘In Portugal, we went to the ministry and it was a warm sunny day when we started negotiating the financing agreement,’ Strauch said. ‘Despite the grave situation for the country, it made it feel more manageable in that moment.’

Continue reading

[1] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2011), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Portugal’, European Economy Occasional Papers 91, p. 5, June 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2011/pdf/ocp79_en.pdf

[2] Eurostat (n.d.), ‘General government deficit (-) and surplus (+) – annual data’, 2006–2017. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=teina200

[3] MarketWatch (2010), ‘Portugal downgraded to AA- by Fitch’, 24 March 2010. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/portugal-downgraded-to-aa-by-fitch-2010-03-24

[4] Bloomberg (2011), ‘Portugal’s Credit Rating Is Cut to Junk by Fitch on Debt’, 24 November 2011. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-11-24/portugal-s-credit-rating-cut-to-junk-by-fitch

[5] European Commission (2011), ‘Joint statement by the European Commission and the European Central Bank on the measures announced by the Portuguese government’, 11 March 2011. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-11-164_en.htm

[6] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2011), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Portugal’, European Economy Occasional Papers 79, p. 15, June 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2011/pdf/ocp79_en.pdf

[7] Ibid.

[8] Tumpel-Gugerell, G. (2017), EFSF/ESM financial assistance: Evaluation report, Publications Office, Luxembourg. https://www.esm.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ti_pubpdf_dw0616055enn_pdfweb_20170607111409_0.pdf

[9] European Commission (2011), ‘Portugal: Memorandum of understanding on specific economic policy conditionality’, 17 May 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/eu_borrower/mou/2011-05-18-mou-portugal_en.pdf