32. Clean exit: Portugal wraps up its programme

The ESM proved its mettle in setting up the assistance programme for Cyprus, building on its success in providing bank-focused aid to Spain. One of the next challenges would be not just how to start a rescue programme, but how to help countries cement their recovery.

In late 2013 and early 2014, EFSF programmes in both Ireland and Portugal were coming to a close. Ireland’s economy had bounced back strongly and, by mid-2012, financial markets were willing to lend again without a euro area safety net. Portugal’s outlook was less certain. It began syndicated sales to banks in 2013, but its auction debut would have to wait until April 2014[1]. The successful €750 million return to markets was seen as evidence that Portugal would be able to exit its EFSF programme, but at that time markets questioned if it should keep some sort of lifeline open to the firewalls.

Of all of the ESM’s new tools, the precautionary credit line was the one that seemed most useful for Portugal given the circumstances. Modelled after similar arrangements offered by the IMF, the tool was designed to help countries maintain or restore market access without taking on new loans and a whole new programme. By agreeing to a set of economic policies and monitoring protocols, countries could have access to a credit line that would ensure they would not run out of money overnight. In turn, the very existence of that credit line would encourage markets to keep lending, ideally allowing the aid money to remain untapped. The idea was that this process would create a virtuous circle of momentum, and then they would not need a full financial assistance programme again.

The main argument for taking a precautionary credit line was that it would reassure markets that Portugal wasn’t on the brink of running out of cash, allowing an easier transition back to market financing. On the other hand, it would paint Portugal in a different light from Ireland, which didn’t need one. In addition, should Portugal decide to request aid, it would have to negotiate a new round of conditions with its euro area peers and then get those conditions through its national parliament.

ESM Chief Economist Strauch said Portugal’s conundrum and eventual decision to go it alone were a product of the political and financial conditions of the time. ‘They could get back to the market. They could finance themselves, but it would have been very useful to keep a bit more pressure on them to continue the reforms. That incentive was lost,’ Strauch said. ‘The Irish, by creating the clean exit as the role model, meant the Portuguese had to go towards a clean exit. We just had to see how it went.’

In 2013, although relations with the troika of international institutions were good, public resentment in Portugal was brewing and political ownership of the programme – and its conditionality – was slipping. ‘As the recession went on too long and the social uproar against austerity policies became stronger, formally supported by the decisions of the constitutional court, the government became more reluctant to assume ownership of the programme and slowed the structural reform momentum,’ said Teixeira dos Santos, former Portuguese finance minister.

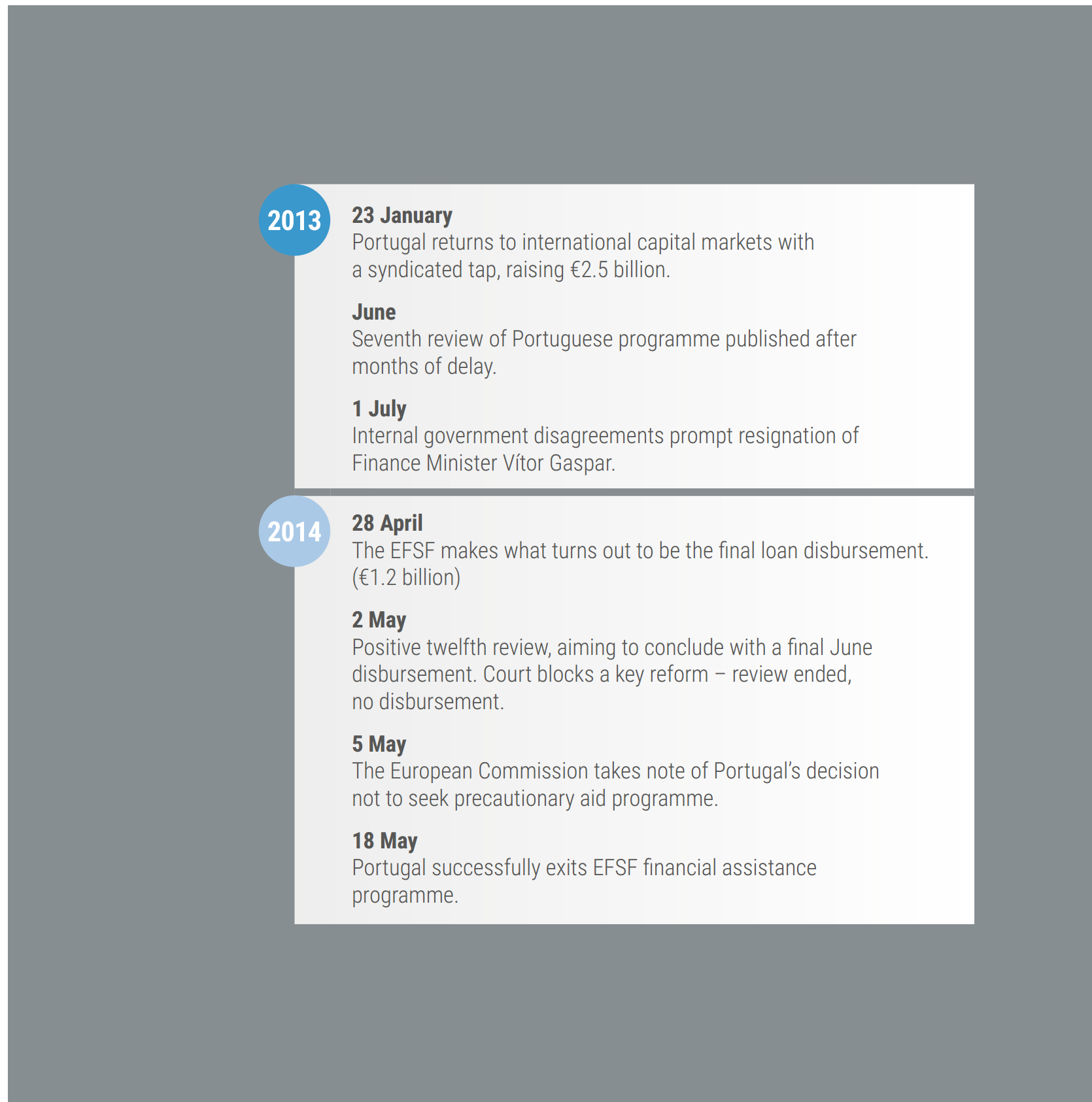

The programme’s seventh review, in 2013, foreshadowed troubles ahead[2]. That review dragged on for three months, a long time by Portuguese programme standards. It was marked by internal government disagreements, leading up to the July 2013 resignation of the finance minister, Gaspar, as well as increasingly drawn-out negotiations with the troika. Tax reforms, in particular, put a strain on workers, which ‘created a political problem and then the ownership of the programme deteriorated,’ Strauch said.

As relations broke down, Portugal took a different view from the euro area institutions on whether or not it should apply for a precautionary programme to ease its return to market access. At the time, Teixeira dos Santos, whose government lost the elections shortly after the programme’s start in May 2011, said he favoured a precautionary instrument because ‘Portugal would have been more protected.’ In hindsight, he says he is glad that ‘market developments were positive and there was no need for it.’

Albuquerque, who took over as finance minister from Gaspar, defends Portugal’s decision not to use it. In her view, the country’s progress on meeting targets during the programme, restoring credibility, and regaining market access meant the country had more options as its assistance period ended.

Even several years on, she still believes it was a good decision to hold back from another programme. ‘A follow-up or precautionary programme can be very important if market access is fragile,’ she said. ‘On the other hand, if you can complete the programme like Ireland did, like we did, having regained credibility and full market access, then the need for a precautionary or a follow-up programme is not obvious,’ Albuquerque said. ‘It’s seen as a lack of confidence. There’s a lot of psychology involved.’

There was also the question of whether or not the euro area partners wanted to authorise use of the new instrument. Misgivings included uncertainty about what new conditionality might entail, and how that might complicate internal deliberations, as well as questions about whether or not the benefits of such a short-term facility outweighed the negative signal its uptake would send to markets, according to the independent EFSF/ESM financial assistance: Evaluation report published in June 2017[3].

Germany and other countries were against Portugal seeking a precautionary credit line, a view reinforced in 2016 by Germany’s then-Finance Minister Schäuble. ‘Portugal did not do so, and I thought it made the right decision,’ he said. Nevertheless, he noted that progress on banking sector reforms and on bringing down high levels of corporate and public debt got harder after the programme ended. ‘I am aware that post-programme surveillance became weaker without a precautionary credit line.’

Albuquerque disputes this. Portugal was already due for extra scrutiny as a result of its rescue package and adjustment programme. It faced a series of post-programme reviews and the EU’s European semester process of national budget coordination. She says the precautionary programme would not have meant much change, and the government’s decision against using it was not taken to avoid extra oversight.

At the European Commission, officials held a much blunter assessment of Portugal’s prospects for going it alone. ‘With Portugal we had strong doubts that it would be wise to go out without a follow-up,’ said the Commission’s Buti. ‘There was a devilish alliance between the country itself and the hardliners. Why? Because the country itself wants to declare victory and the hardliners, they don’t want to push a precautionary programme through their parliament. Moral hazard and taking the jump without a parachute, this is a risk that could come back to haunt us.’

As the decision drew near, ESM officials joined the technical team of monitors and took a bigger role in working with country officials on the economic programme. This move reflected the institution’s growing expertise and its role as one of Portugal’s largest creditors.

From this front-line perspective, the firewall had a clear view of what was at stake as Portugal’s decision approached.

‘Since Ireland had already managed to exit the programme without any follow-up, treating or pushing Portugal too much not to follow the same approach would be extremely costly,’ said Rojas, head of the ESM’s economic and market analysis team, who also served as ESM country coordinator for Portugal. ‘It was basically a political decision.’

Portugal did not have the same quality of ready market access that Ireland or Spain enjoyed. Rojas said this was in part because of how it traditionally sold its debt, through syndication that relied on a small group of would-be buyers. It was also generally more vulnerable to contagion when there was a crisis flare-up in Greece or elsewhere in the euro area. ‘Portugal was borderline at the time,’ Rojas said. ‘In the case of Ireland, market access was decent. In the case of Portugal, it was less so.’

Even with the precautionary programme option now a distant memory, Portugal has remained more susceptible to financial market shockwaves than Ireland or Spain. Portugal’s debt levels remain high and potential growth weak, burdened in part by a banking sector that is still recovering from the crisis. A government push to recapitalise banks helped the financial sector; however, banks remained a source of instability after the programme, in part because of weaker economic conditions, which reduced their asset quality and capital.

The reform efforts in Portugal had lost traction even before the programme ended, especially given a constitutional court decision requiring some public sector wage cuts to be rolled back. This made the ‘clean exit’ decision all the more difficult to digest for the monitoring institutions.

In the end, not only did Portugal not seek a precautionary aid programme, it even skipped its final IMF and EFSM disbursements because it never completed its last review. This came after its constitutional court overturned a law, without which it couldn’t meet the conditions necessary to unlock the aid. ‘At the end of the programme, I would have preferred if we had completed the last review as scheduled, instead of having it end through the lapse of time. I would have preferred a proper closure,’ Albuquerque said. The last EFSF disbursement that Portugal received came in April 2014.

The next milestone will come in a few years’ time, when Portugal begins to pay down its EFSF loan[4]. Following a full repayment of its IMF loan, Portugal has committed to do so earlier than expected[5]. It is currently under the ESM’s early warning system aegis, allowing the firewall to keep a close eye on its finances and economic management. A key test will be if the country is able to continue reducing its debt levels and managing the costs of rolling over its existing stocks of marketable debt.

‘In any case, things are looking brighter. We are at a more advanced stage now, where we can see the bigger picture, see how the economy and its banking system are recovering and what this means for its capacity to repay,’ said Sušec, the ESM’s deputy head of strategy and institutional relations, who also serves as mission chief in Portugal. In that context, the significant reduction in the fiscal deficit has been very encouraging.

‘Portugal has made great progress in restoring its public finances and fixing its banking sector. One of the issues which we still follow closely is the high level of sovereign debt, which makes the country vulnerable to sudden changes in market conditions.’

Continue reading

[1] For a fuller assessment of how four programme countries approached the restoration of market access, see Strauch, R., Rojas, J., O’Connor, F., Casalinho, C., de Ramón-Lapa Clausen, P., Kalozois, P. (2016), Accessing sovereign markets: The recent experiences of Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Cyprus, ESM, Discussion Paper 2, 20 June 2016. https://www.esm.europa.eu/sites/default/files/esmdp2final.pdf

[2] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2013), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Portugal: Seventh review – winter 2012/2013’, European Economy Occasional Papers 153, June 2013. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2013/pdf/ocp153_en.pdf

[3] Tumpel-Gugerell, G. (2017), EFSF/ESM financial assistance: Evaluation report, Publications Office, Luxembourg. https://www.esm.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ti_pubpdf_dw0616055enn_pdfweb_20170607111409.pdf

[4] European Commission (n.d.), ‘Financial assistance to Portugal’. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/eu-financial-assistance/which-eu-countries-have-received-assistance/financial-assistance-portugal_en

[5] EFSF (2018), ‘EFSF approves waiver of Portugal’s mandatory repayment of EFSF loans’, Press release, 4 December 2018. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/efsf-approves-waiver-portugal%E2%80%99s-mandatory-repayment-efsf-loans