Unlocking banks’ capacity to fund the recovery

During the pandemic, firms and households needed support to survive economic hardships caused by lockdown. Policy makers took unprecedented measures to extend credit to the economy. Looking back, we can draw lessons from banks’ behaviour during this period. While banks did successfully help avert a liquidity squeeze, they did not take full advantage of the capital space regulators provided due to constraining market forces. In such crisis situations, clear alignment of expectations among stakeholders is a pivotal issue to enable the banking industry to take full advantage of regulatory leeway. Looking forward, completing banking union could dissipate a significant part of market concerns via the strengthened safety net which will support real growth.

Credit crunch averted

Europe’s unprecedented policy effort helped avert a credit crunch and led to increased private sector lending.

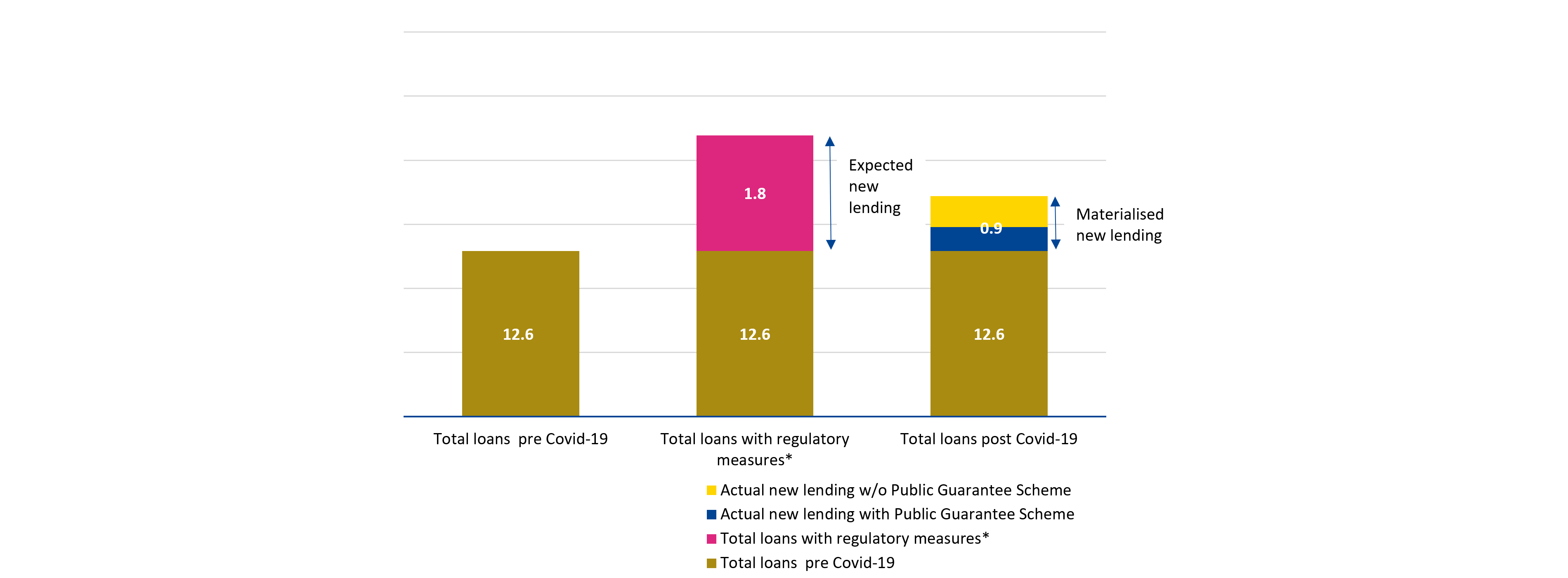

The timely and concerted support measures implemented by EU and national institutions ensured that banks continued providing new lending to the economy during the pandemic. At the euro area level, outstanding loans to the non-financial private sector stood at €12.6 trillion before the crisis, and they increased by approximately 7% to €13.5 trillion by the end of 2021.

But while lending increased in absolute terms, this was still less than had been expected by policymakers and was achieved without banks dipping into their additional capital buffers.

During the pandemic, regulators lowered some operational requirements, allowing for the use of certain capital buffers. Yet banks have not entirely used these buffers. As of Q3 2021, only six euro area banks made use of the relaxation of capital requirements and took on risks over the previous limits. As a result, at the end of 2021, the realised lending was half of what the available capital space would have allowed (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Outstanding loans in the euro area before and after the pandemic crisis

(€ trillion)

Notes: pre Covid-19=December 2019, post Covid-19=December 2021. Total loans excluding Monetary and Financial Intitituions (MFIs). *As introduced[1] and estimated[2] by the ECB banking supervision and national macroprudential authorities. PGS: Public Guarantee Scheme.

Source: ESM calculations based on European Banking Authority and European Central Bank

Demand for credit

It is difficult to assess the extent to which demand drives lending, particularly in uncertain and crisis times. During the pandemic, most of the funding needs of the private sector have been likely met via extraordinary policy support measures (e.g., direct fiscal support to firms and more market funding possibilities) and bank lending. The ECB’s Bank Lending Survey[3] suggests that on average, the majority of euro area banks did not perceive a persistent decline in firms’ loan demand in the last two years. In fact, banks continued to report increasing demand for corporate loans since the second half of 2021. Firms - in particular Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (SME), reported increased demand and accessible credit conditions during the initial year of the pandemic, with the exception of some countries. However, SMEs perceive demand exceeding supply according to the latest Survey on Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE)[4] and the EIB Investment Survey[5].

Supply of bank loans

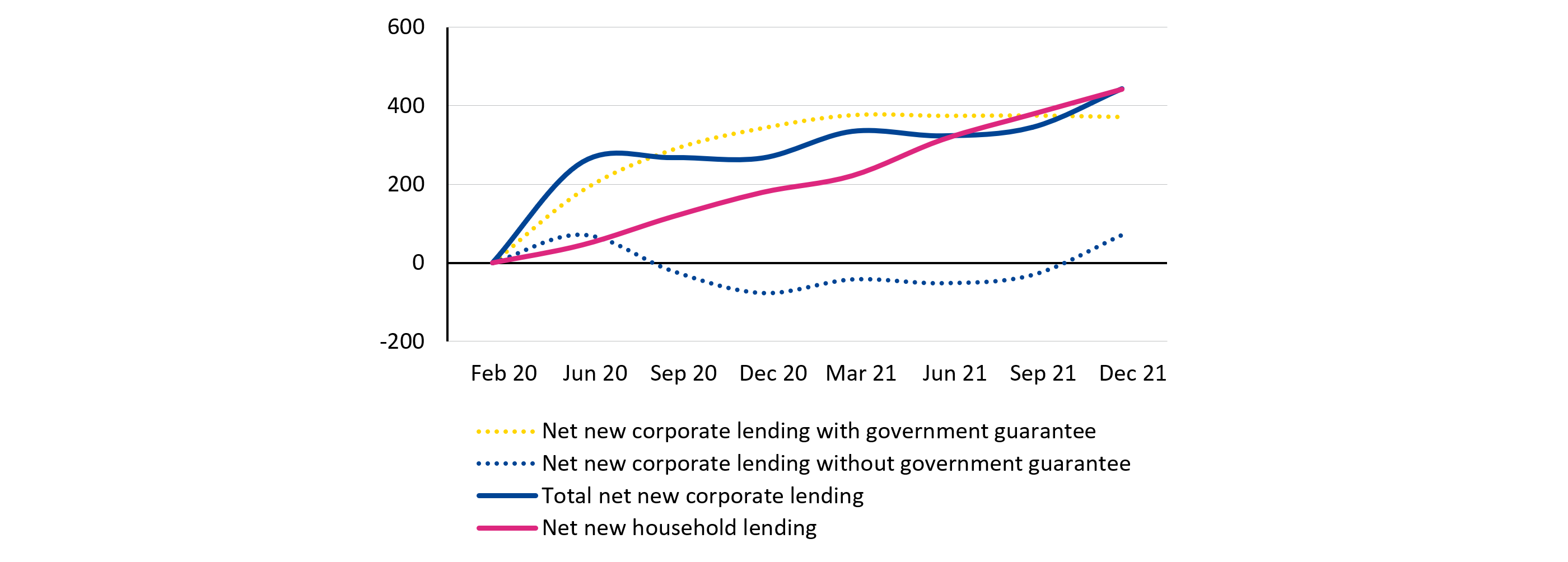

On the supply side, beyond the lower than anticipated volumes, banks have largely stayed away from uncollateralised, higher risk loans during this period. Most lending was lower risk, state-guaranteed corporate lending and mortgages. Until the third quarter of 2021, net new lending to firms was in positive territory only thanks to the considerable amount of state-guaranteed lending that carries marginal risks for the banks (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Cumulated change in net new lending

(February 2020 = 0, EUR billion)

Source: ECB, EBA Risk Dashboard, ESM calculation

These developments leave us with the question why banks did not make use of the additional capital space that was created. We will address this question in two ways: how investors’ perceptions influenced banks’ behaviour; and how banks’ underlying vulnerabilities affected their lending and capital strategy.

Investors’ risk perception dampers new lending

Amid the high uncertainty of the pandemic, banks seemed to act, not on regulatory expectations, but more upon market perceptions. They used their capital conservatively, either lending at low risk or not at all. Banks dipping into their capital space may be stigmatised by markets, resulting in higher funding costs, a fall in bank’s equity shares, and rating downgrades. The perceived uncertainty on the exit strategy from the capital relief measures and the historically low profitability of the sector influenced largely market participants, which was then reflected in banks’ lending decisions.

Due to the temporary nature of the capital release, the expected return on an additional new loan needs to cover the capital costs during an unknown, but supposedly short, period of time that would be available to rebuild their buffers. In a low interest rate environment - in which profitability is already highly challenged - the repayment of capital takes long and riskier loans need to be carefully priced over a certain time horizon. Eventually, the uncertainty created by a new type of crisis and the policy response measures make it extremely difficult for the banks to properly assess the borrowers’ creditworthiness and price the loans. The intrinsically riskier nature of uncollateralised corporate loans and SME lending paired with a higher regulatory cost and an uncertain time horizon resulted in banks focusing on low-risk lending to avoid future restrictions on dividends, additional Tier 1 coupon payouts and share buybacks.[6]

The driving role of market expectations in shaping banks’ behaviour during the pandemic crisis is well reflected in banks’ managerial capital targets. These targets, which are the focus of banks’ management of their business decisions and a key metric for investors, remained broadly unchanged despite the space that had been created by the capital relief measures.

The shadow of banks’ vulnerabilities

Banks’ cautious capital management can also be traced back to pre-existing vulnerabilities. Focusing on the sample of banks directly supervised by the Single Supervisory Mechanism, we analyse a few pre-Covid characteristics of banks that report a lower growth rate of total loans between the final quarters of 2019 and 2021. We observe that banks that had higher non-performing loans (NPLs), weaker profitability, and riskier portfolios have lent less overall. Not surprisingly, these are also the banks that entered the crisis with seemingly comfortable buffers but with the least risk appetite as buffers are locked to cover a credibility gap due to legacy issues. This is because NPLs absorb more capital vis-à-vis performing loans while low profitability impairs banks’ future organic capital generation ability, incentivizing banks to preserve their buffers. Overall, this suggests that a considerable part of the buffers accumulated in the system remain rigid and insensitive to current economic developments.

Banks’ risk appetite booster

As we have seen, banks did not adapt their capital targets in line with the reduced capital requirements. Also, those banks that showed willingness to lend engaged mostly in low-risk segments to minimise capital costs. These reactions resulted in a conservative use of capital, which made banks commendably safe, but also unduly constrained credit supply. From the analysis above, two areas emerge that could help to unlock additional bank lending. Firstly, better align markets’ risk perceptions and expectations by coordinated policy measures. Secondly, further strengthen banks’ fundamentals to unlock accumulated capital.

In an uncertain environment, to increase banks’ risk appetite and to convince markets about the beneficial effects of a healthy risk-taking, there is a need to provide clear forward guidance upfront. Clear communication will shape financial market expectations, ultimately helping reduce the stigma associated with banks’ drawing on their buffers. Moreover, it could serve for banks’ management to better include them in their expectations and medium-term business models.

During past crises as well as the most recent pandemic, European regulators had relied on partnership and close cooperation. A deep dialogue among authorities may help unlock additional lending capacities. Coordination is required to prevent situations where the share of buffers linked to the performance of the economy, such as the Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB), is not enough to address risks. In addition, coordination helps to avoid misalignments whereby other regulatory requirements - such as the leverage ratio or the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL) – render relaxation of capital requirements less effective simply because they remain more binding than risk-based requirements.

Further improvements in banks’ fundamentals is also necessary to maximise the use of accumulated capital buffers. Profitability and capital generating capacity is key for a healthy bank. European banks have worked on cost cutting and pushed digitalisation during the pandemic. But there is further room to improve business models and efficiency. Some further consolidation is still necessary to structurally improve the health of banks.

Completing the banking union could facilitate progress in all these aspects. The strengthened safety net could dissipate a significant part of market concerns. It would also naturally facilitate and strengthen coordination between institutions. Moreover, it would remove long-standing barriers that prevent better capital allocation within banking groups. By facilitating cross-border operations of banks, it allows for risk-sharing across countries and a better provision of bank services – including credit – across the euro area.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Nicoletta Mascher, Paolo Fioretti, Peter Lindmark, George Matlock and Mariia Penina for their valuable comments to this blog.

Further reading

From savings to spending: Fast track to recovery

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors