Regional perspectives on the economic impact of a double shock: Asia, Europe, Latin America

Regions across the globe have been facing a double shock from the pandemic itself and from pandemic-induced supply disruptions while economies were recovering. This double shock is now exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. Three Chief Economists at crisis prevention and resolution mechanisms in Asia, Europe, and Latin America describe the different economic developments, risks, and challenges in their respective regions.[1]

Since the pandemic hit two years ago, unprecedented measures have been taken to address the initial shock waves. While some economies bounced back fairly quickly, the ability of countries to withstand the economic damage and control the disease varies widely – as does the speed of the economic recovery. Amid this environment, supply disruptions and energy price hikes triggered a supply shock that the war in Ukraine now exacerbates. Energy and food prices have become major inflation drivers, putting pressure for monetary stimulus to be withdrawn while the recovery is still nascent in many economies. Inflationary pressures hit those hardest who face difficulties in covering the needs of their daily life everywhere.

In this blog, we describe the impact of this double shock across the regions where we work: Asia, Europe, and Latin America. We also highlight the challenges and risks policymakers face when dealing with this double shock.

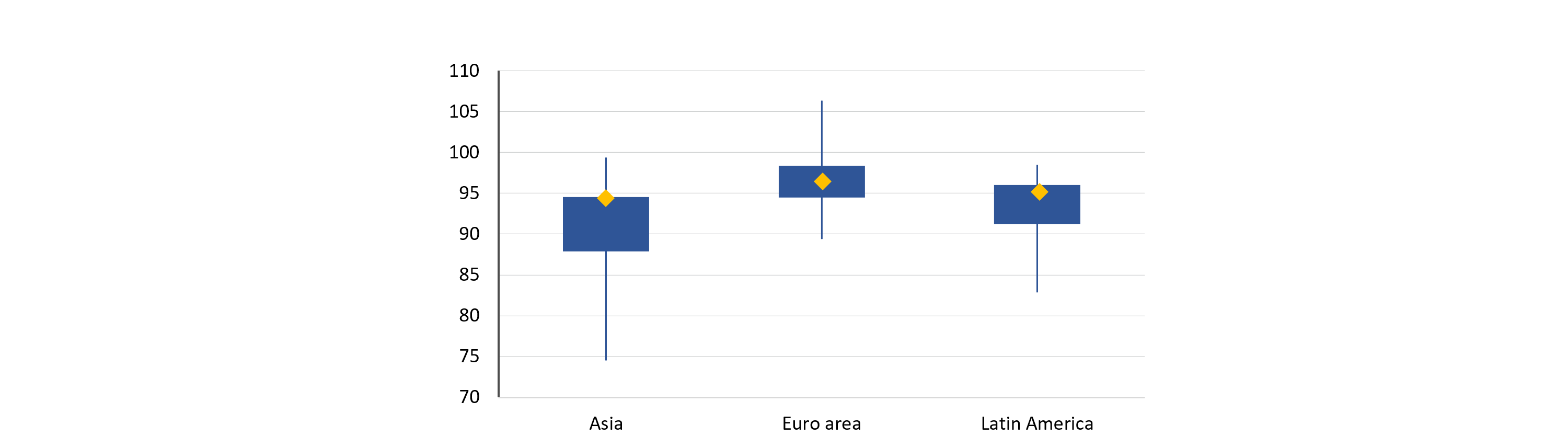

Figure 1: GDP gap in 2021 compared with pre-pandemic trend

Source: Calculations based on International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook data

Notes: Asia refers to AMRO member countries, euro area refers to ESM Member countries, and Latin America refers to FLAR member countries plus Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Box plots refer to the area between the 25th and 75th percentile for country groups, whiskers refer to minimums and maximums, and diamonds refer to purchasing power parity adjustments. GDP is weighted average and gap refers to the percent of real GDP in 2021, compared to the scenario where average GDP growth over 2010–2019 had stayed constant in 2020 and 2021.

Asia (ASEAN+3): a bumpy road to recovery with a resilient financial sector

After two years, Asian economies are now recovering more strongly from the pandemic. However, the recovery is multispeed and uneven. While some economies have surpassed their pre-pandemic output levels in 2021 (e.g., Korea and Singapore), others are likely to do so only in 2023 (e.g., Thailand). This divergence reflects, to some extent, scarring effects from the pandemic, given that some economies are more dependent on high-contact social industries such as tourism.

The new wave of Covid-19 infections in China, and the stringent measures to contain its further spread, have added new uncertainties for the region. The extended lockdowns across major Chinese cities threaten to disrupt regional production line and supply chains, ensnaring industries from automotive to consumer goods. This comes at a point where the region is contending with the consequences of the war in Ukraine, which has driven prices for energy and major agricultural commodities to record highs, posing upside risks to inflation.

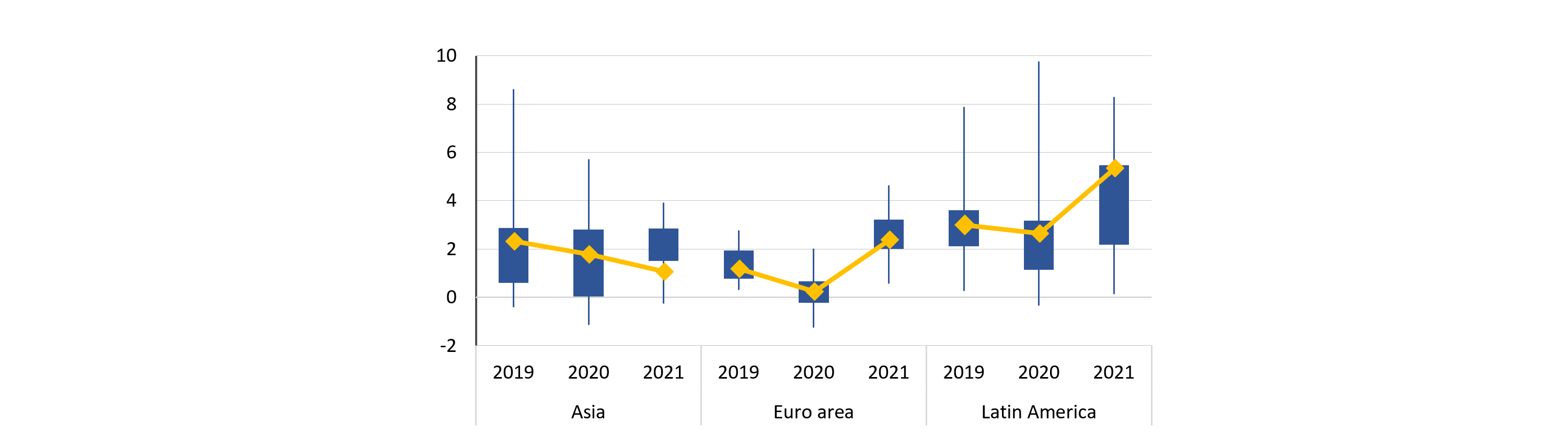

Notwithstanding the risks, regional headline inflation has remained relatively low, albeit increasing. The low inflation partly reflects price stabilisation mechanisms to help keep prices of essential goods stable. Unlike other emerging market peers where persistent high inflation has caused central banks to raise interest rates quite significantly, monetary policy in Asia remains broadly supportive of growth. For economies where the output gap has narrowed and underlying price pressures are building, authorities have begun to taper pandemic-era monetary easing.

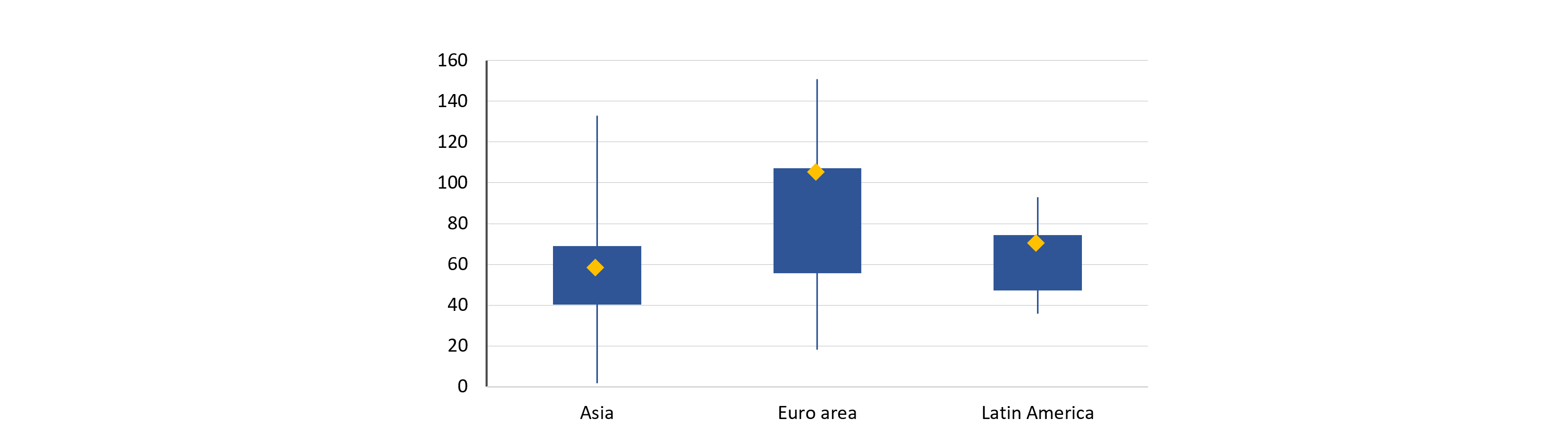

On the fiscal front, most regional economies entered the pandemic with moderate-to-ample policy space and reserves, thanks to sound and prudent public finances. The proactive and exceptionally large stimulus programmes introduced to counter the economic fallout of the pandemic have been followed by a more targeted approach since last year. Recognising the need to rebuild fiscal space, most regional economies have now shifted to consolidate their fiscal position, while continuing to provide targeted support to vulnerable groups. While the debt-to-GDP ratio has risen across the region, much of the increased debt is domestic and the debt service burden is manageable.

The financial system remains resilient. Monetary easing and regulatory forbearance measures have supported liquidity in credit markets and allowed banks to perform their intermediary functions. Looking ahead, financial stability risks stem from more aggressive tightening by the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank (ECB) to rein in inflationary pressures, which may trigger a more pronounced global slowdown, sharp repricing of risk assets, and disorderly market functioning. These risks could also collide with further escalation of sanctions, contributing to financial stress and undermining the region’s recovery.

Figure 2: Government Debt in 2021

(in % of GDP)

Source: Calculations based on International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook data

Notes: Asia refers to AMRO member economies, euro area refers to ESM Member countries, and Latin America refers to FLAR member countries plus Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Calculations exclude Venezuela (307% of GDP), Japan (263% of GDP), and Greece (199% of GDP). Box plots refer to the area between the 25th and 75th percentile for country groups, whiskers refer to minimums and maximums, and diamonds refer to purchasing power parity adjustments. GDP is weighted average.

The euro area: targeted policies help recovery interrupted by war

The euro area recovered strongly from the pandemic, achieving pre-crisis output levels in several countries and it was even set to catch up with its previously predicted growth trend in 2023. The severe terms-of-trade shock linked to energy prices and the Russian war against Ukraine puts a serious dent in the forceful recovery, leaving the region exposed to a stagflationary risks.

Growth expectations were lowered substantially, and inflation remains above 7%, far beyond the ECB’s definition of price stability, although second round effects are so far contained. The loss of income emerging from energy price shifts is similar in magnitude to that of the first oil price crisis in the 1970s. Fortunately, the structure of the labour market, lower energy dependency and intensity, and accumulated savings during the pandemic should render the impact less severe and persistent than in the past. Moreover, the European Next Generation EU (NGEU), a €750 billion recovery fund launched during the pandemic, should improve economic sustainability and digitalisation.

The ECB has embarked on monetary policy normalisation process and is currently phasing out its asset purchase programmes, with interest rate steps to follow in line with inflationary risks. As a result, bond market conditions are equally normalising, while spreads remain relatively contained as markets believe the central bank is committed to avoiding fragmentation of sovereign financing conditions.

Emerging from the pandemic, governments faced the challenge of supporting the economy while building up fiscal buffers. The request for government support is rising in the current environment. Governments have taken targeted and temporary measures to mitigate the impact of higher prices on the most vulnerable and some sectors, along with more broad-based relief. Refugee flows and higher defence needs add to these spending pressures.

The war in Ukraine and related sanctions did not induce financial instability in Europe. However, elevated cyber risk and the operation of highly concentrated commodity markets are often identified as points of concern. For the bank and non-bank financial system, the predominant issue is the further evolution of monetary policy and whether this will lead to unexpected repricing of assets, including in domestic real estate markets. Higher interest rates and lower growth also worsen the credit banks carry on their balance sheets.

Figure 3: Inflation

(% change)

Source: Calculations based on International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook data

Notes: Asia refers to AMRO member countries, euro area refers to ESM Member countries, and Latin America refers to FLAR member countries plus Brazil, and Mexico. Calculations exclude Venezuela. Box plots refer to the area between the 25th and 75th percentile for country groups, whiskers refer to minimums and maximums, and diamonds refer to purchasing power parity adjustments. GDP is weighted average.

Latin America: heterogenous recovery before the war in Ukraine

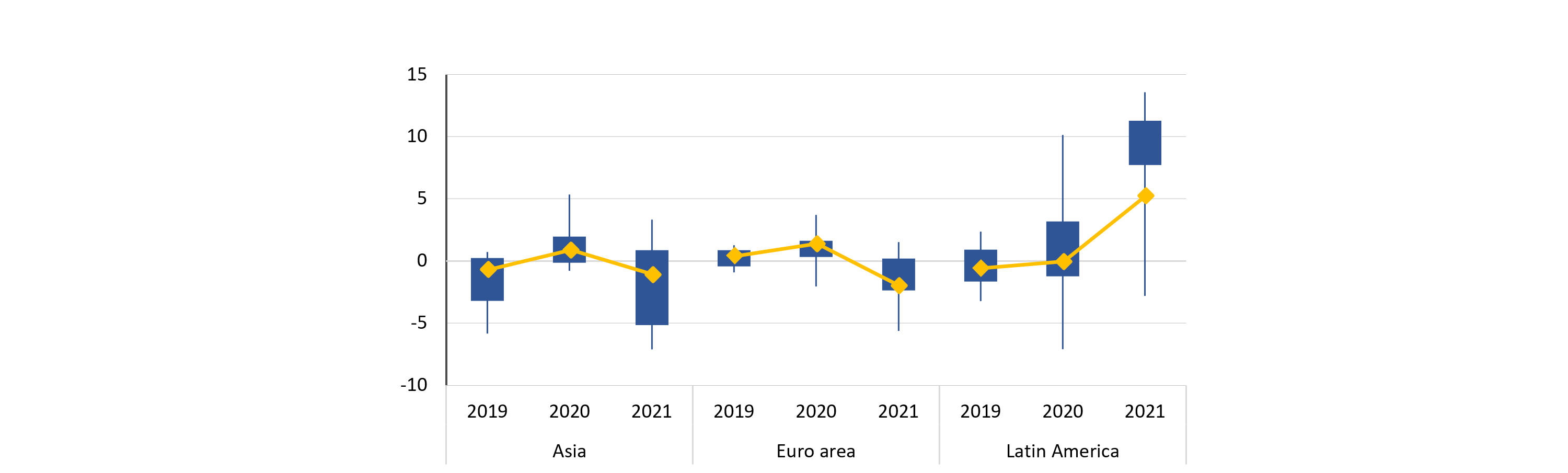

Latin America is showing a heterogenous recovery after suffering a sharp economic downturn during the first year of the pandemic. The recovery is heterogeneous, and depending on the starting conditions, the characteristics and responsiveness of each economy. Several countries in the region have reached pre-pandemic levels of economic activity (e.g., Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Peru). Particularly, net commodity exporting countries, especially in South America, have benefitted from better terms of trade due to price increases in their exports, which has been accentuated by the war in Ukraine. Formal employment recovery has been slow in the region and could suffer from an economic slowdown linked to lower global economic growth.

A major risk to continued recovery and macroeconomic and financial stability is the persistence of high inflation. The war in Ukraine implies an inflationary shock on top of an existing one due to global commodity price inflation. Many of the region's central banks have started to lift monetary measures implemented during the pandemic, including increases in their policy rates at different paces, in line with inflationary risks resulting from supply and demand factors both external and domestic. The monetary policy challenge lies in containing inflation pressures and expectations while favouring the economic recovery process.

In this environment of increasing financing costs in international and local markets, governments face the challenge of continuing the process of fiscal consolidation while protecting the most vulnerable population affected by the after-effects of the pandemic and rising food and fuel prices. Some governments have recently activated subsidy schemes for this purpose.

The financial system remains resilient, following the withdrawal of a large part of the financial relief measures for households and businesses in several countries. In the future, risks of financial instability in the case of an eventual deterioration in economic activity or sudden stops in capital flows remain. The latter may result either because of the effect of a rapid and strong hike in international interest rates, led by the US Federal Reserve, or because of tensions in financial markets stemming from the escalation of the ongoing war in Ukraine. Sudden stops could also arise due to distrust of the economic, political, and/or social sustainability in some countries. Thus, economic authorities face the challenge of implementing measures or reforms to alleviate social discontent while generating investor and consumer confidence in an orderly macroeconomic adjustment process.

Figure 4: Terms of trade

(year-on-year change)

Source: Calculations based on international Monetary Fund and national source data relayed through Haver Analytics

Notes: Asia refers to AMRO member economies, euro area refers to ESM Member countries, and Latin America refers to FLAR member countries plus Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Calculations exclude Costa Rica, Ecuador, Venezuela, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Vietnam due to data gaps. Box plots refer to the area between the 25th and 75th percentile for country groups, whiskers refer to minimums and maximums, and diamonds refer to purchasing power parity adjustments. GDP is weighted average. Terms of trade growth is defined based on national accounts’ expenditure breakdown as the growth of (nominal exports / real exports) / (nominal imports / real imports).

Common policy challenges across regions

All regions – Asia, Europe, and Latin America – are marked by a heterogeneous recovery from the pandemic and the repercussions of the current supply-side shock driving up inflation. The war against Ukraine shows how such shocks propagate globally through international commodity markets – albeit with different impact. The euro area faces the most stagflationary pressures, while also bringing some economic gains to net commodity exporters in Latin America regardless of the inflationary shock. The emerging interest cycle in the US and the euro area, as a reaction to inflation, and a possible escalation of sanctions shape global financing conditions and growth prospects and thus pose financial stability risks to emerging markets.

Monetary policy faces a stronger trade-off between the need to react to inflation and the need to benefit economic growth in Latin America and Europe. Asian economies make more use of price controls. Fiscal policy is everywhere marked by the challenge of protecting the most vulnerable from the impact of the double shock while also creating buffers and deleveraging from the pandemic debt hump. For European economies, it will not be possible to fully compensate the loss of income due to the terms-of-trade shock. Income levels and the impact on the poor varies markedly, something to bear in mind going forward.

Crisis prevention and resolution mechanisms in the global financial safety net, with Regional Financing Arrangements and the International Monetary Fund at the core, need to stay alert in view of the heightened uncertainty and existing downside risks to growth. Some comfort can be taken from the resilience built up in the global financial system through reserves and within financial institutions. However, sudden repricing and changes in financial flows may melt down buffers, and existing vulnerabilities, such as high debt levels, may exert instability.

Acknowledgements

We thank Edmund Moshammer (ESM) for his valuable input to this blog.

Further reading

Regional Financing Arrangements (RFAs) | European Stability Mechanism (esm.europa.eu)

Same crisis, different responses to Covid-19 | European Stability Mechanism (esm.europa.eu)

Footnotes

Hoe Ee Khor is Chief Economist at the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO).

Rolf Strauch is Chief Economist at the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Blog manager