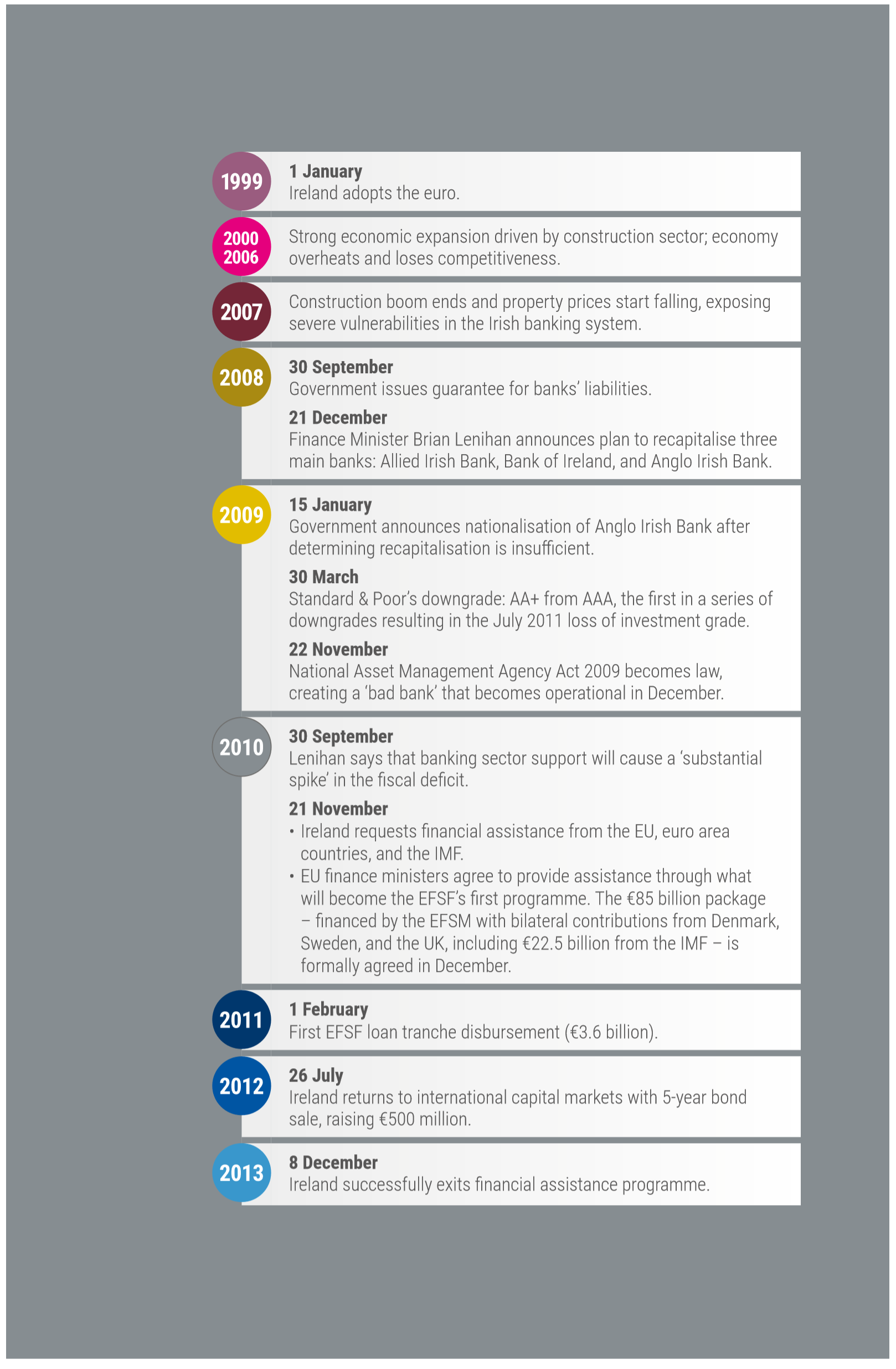

10. Testing the EFSF: the case of Ireland

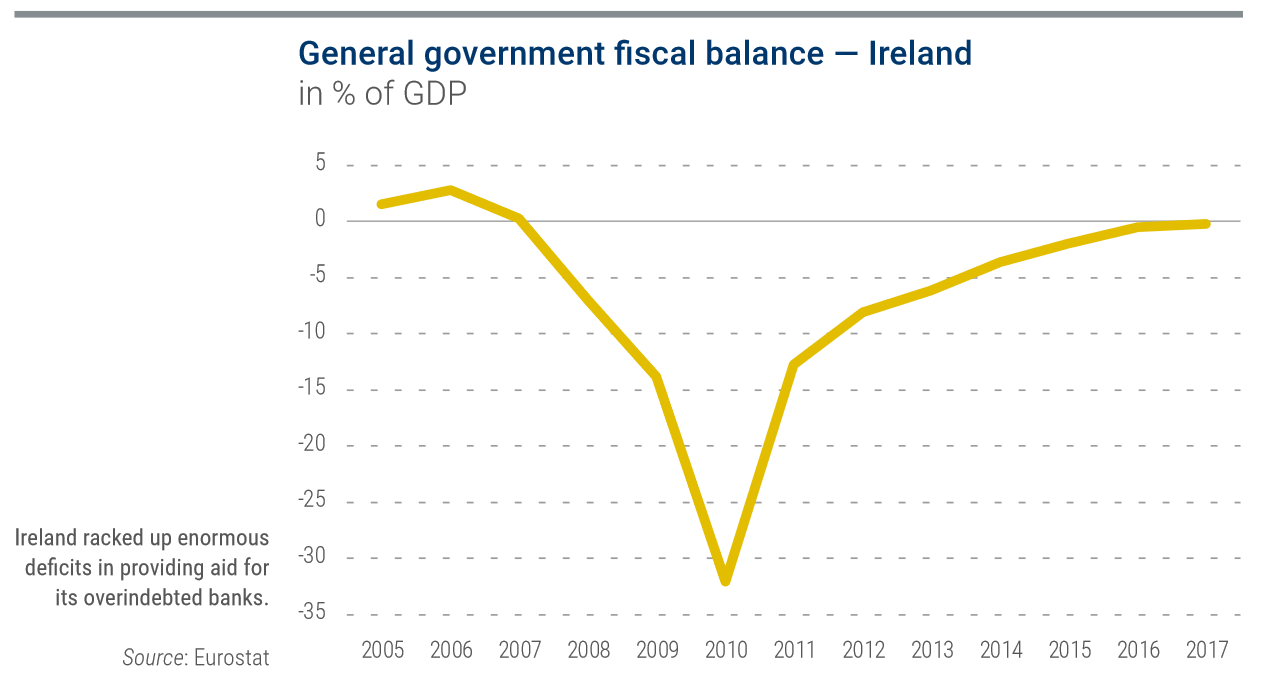

A potent mix of recession and banking crisis had pushed Irish government finances to the edge. With better bank governance and an eye towards fending off the worst excesses of a boom-bust cycle, Ireland might have been able to avert the debacle. Instead, policymakers not only struggled to tame the excesses, they overextended government finances to rescue the banks amid concerns that failure to support them would have had its own extensive costs.

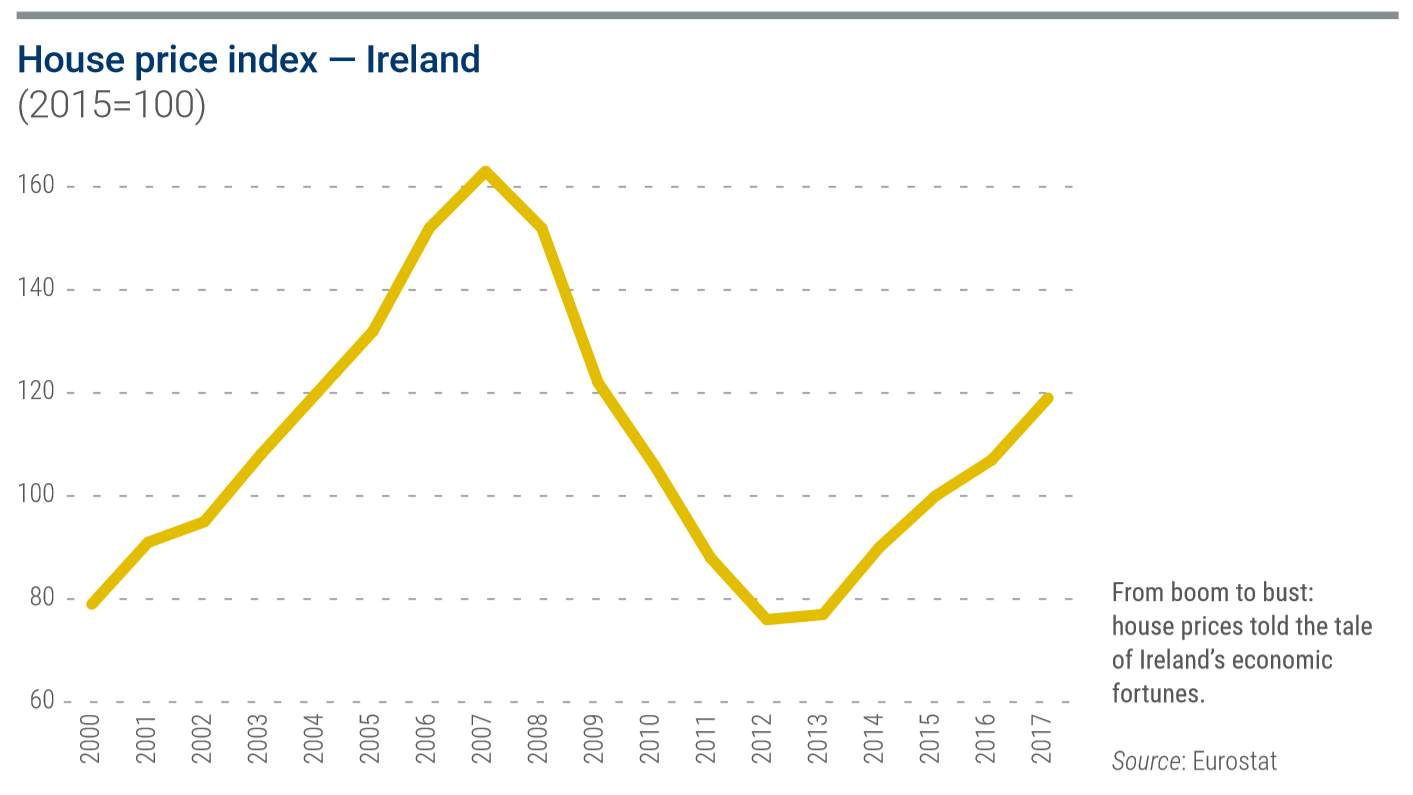

When Ireland turned to Europe’s brand-new firewall, it had already spent two years trying to curb its housing boom and pull its banks onto a more even keel. It was an uphill battle; Irish culture strongly favours home buying, and Ireland had never experienced a widespread real estate bust. On top of that, aggressive banking practices encouraged borrowers to take on ever more credit, in turn saddling the banks with life-threatening levels of bad loans. When the US financial crisis hit in 2008 and sparked global banking turmoil, the Irish banks were especially vulnerable.

In September 2008, in a bid to preserve financial stability the Irish government offered a sovereign guarantee of bank liabilities[1]. The Irish Times said that covering up to €440 billion of customer deposits and banks’ own lending was ‘the biggest financial gamble, and arguably the biggest policy decision, ever taken by an Irish government’[2]. Brian Lenihan, then-finance minister, said the Irish banking sector support would lead to a ‘very substantial spike’ in the fiscal deficit[3].

The move made the Irish taxpayer responsible for losses, but even that wasn’t enough. In December 2008, the government announced a bank recapitalisation programme, and in January 2009 it nationalised Anglo Irish Bank[4]. That November, it rolled out the National Asset Management Agency[5] to tackle the bad-loan backlog and remove the riskiest land and property development loans from the banks’ balance sheets.

Ireland’s situation triggered debates on when and how governments should step in and who should pay the price for failure. Throughout the crisis, Ireland was under heavy pressure from the ECB and others in the EU to protect senior bank bondholders, who enjoy a privileged position in the payout order in the event of a default. The senior bondholders maintained that advantage even later on, when losses could be imposed on junior creditors as part of the clean-up efforts. Although the ECB had supported the Irish bank guarantees in an October 2008 statement[6], Ireland’s national guarantee on its banks’ obligations came to be seen as a mistake.

Regling and Watson’s joint analysis of Ireland’s crisis, published in June 2010, found a number of ‘home-made’ factors that aggravated the impact of the crisis. ‘Official policies and banking practices in some cases added fuel to the fire,’ the report said. ‘Fiscal policy, bank governance and financial supervision left the economy vulnerable to a deep crisis’[7].

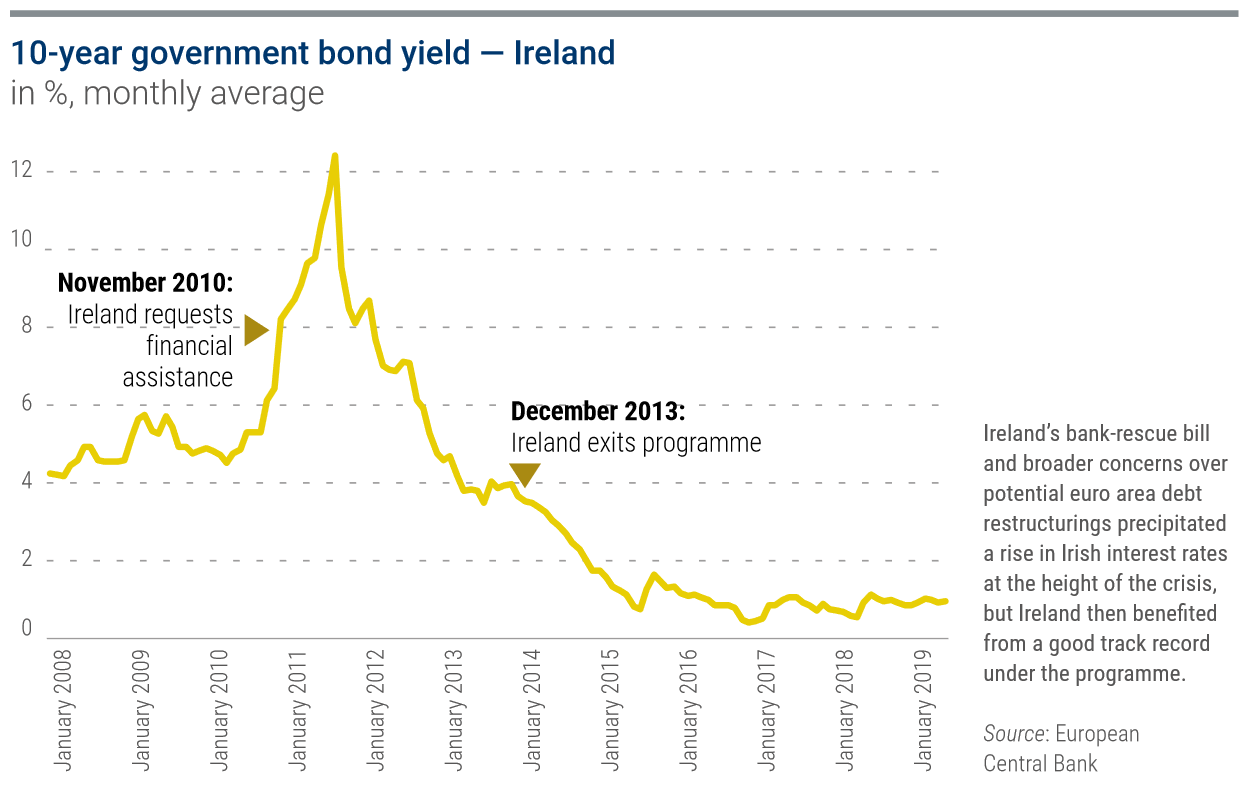

In early May 2010, heading into the crucible weekend that forged the EFSF, markets were requiring high-risk premiums on Irish, Greek, Spanish, and Portuguese debt. Ireland was further slammed by a virtual shutdown in interbank lending among European banks, another sign of a looming systemic crisis. By August 2010, the two-year sovereign bank guarantee was scheduled to expire and bond yields were heading up, while economic growth was slowing. In September, spreads reached a high of 449 basis points, meaning Ireland faced borrowing costs 4.49 percentage points higher than its top-rated euro area peers. Shortly thereafter, new estimates put its total expected bank rescue bill at €45 billion[8].

Then, on 18 October 2010, German Chancellor Merkel and French President Sarkozy took a walk on the beach in Deauville, France, and emerged with a handshake agreement that private investors shouldn’t be immune from losses in future sovereign debt crises. This meant that losses for creditors and investors, often called ‘haircuts’, could become de rigueur if euro area countries found themselves with unsustainable debt and in need of aid. The deal was struck as part of a broader agreement[9] between France and Germany that aimed to improve the bloc’s budget rules as well as its rescue mechanisms.

The idea of enshrining debt restructuring in perpetuity sent shockwaves across the world’s bond markets, which have traditionally treated sovereign debt from developed countries as low-risk, or even risk-free, investments. In a 27 October speech to the Bundestag, Merkel explained that the Deauville compromise included plans to make bondholders, such as banks and hedge funds, share some of the costs of risky lending by sharing responsibility for coming to the rescue of states on the brink of insolvency. For France, the subject of an EU ‘excessive deficit’ procedure from 2009 to 2018[10], agreeing to ‘adequate participation of private investors’ – that is to say, writedowns – was the price of securing a German retreat from a proposal to apply automatic sanctions to countries that flouted the rules of the stability and growth pact, according to observers[11].

‘The compromise was an awkward one: France agreed to start discussions on a German demand for a permanent crisis resolution framework ensuring that private creditors would share the burden of debt restructuring. In exchange, Germany renounced the idea of automatic sanctions for countries in violation of the fiscal discipline provisions of the stability and growth pact,’ wrote Jean Pisani-Ferry, a former policy advisor to the French government, in his 2014 book, The euro crisis and its aftermath[12].

Financial markets were jolted by the debt-restructuring element of the deal. Some policymakers said it added to contagion woes in the euro area.

‘The Deauville deal came unexpectedly. It showed that premature and spontaneous talk on debt restructuring can be very damaging to the credibility of the euro zone in financial markets,’ said Rehn, at the time the European commissioner for economic and monetary affairs and the euro. ‘When the Deauville deal was done it was lose-lose, both in terms of watering down the sanctions and in terms of prematurely and spontaneously raising the possibility of a debt restructuring.’ Trichet, then-ECB president, said that at the EU summit of 28 and 29 October 2010 he had opposed the Deauville agreement, because it would be understood as an open invitation to speculate.

Government borrowing rates skyrocketed in Ireland, where the government’s balance sheet had ballooned, and the banks were receiving unsustainable levels of emergency support from the central bank. The Deauville deal directly put Ireland on the path to losing its market access, said Trichet. It also added to the re-pricing of risks that had already started in the markets. Investors began differentiating among euro area countries as never before, with a particular focus on countries that had accumulated large economic imbalances. Taken together, these developments amplified the contagion that would push Ireland into a rescue programme within weeks.

‘People tend to forget,’ Rehn said. ‘It was not evident that Ireland had to go into a programme. Probably they would have, but we don’t know that.’

On 4 November 2010, Ireland announced record budget cuts of €15 billion[13], but the yield on its 10-year bonds rose anyway to average a punishing 8.22% that month. Spreads to the 10-year German Bund widened that day to 526 basis points. At such elevated levels, sovereigns typically refrain from long-term issuance. The ECB also began putting pressure on Dublin to seek broader assistance.

At this point, Irish banks were heavily dependent on the ECB’s tool for solvent financial institutions that are experiencing temporary cash flow problems, Eurosystem emergency liquidity assistance. Trichet later said that the total liquidity supply coming from the Eurosystem to Ireland was the largest in the euro area, surpassing 100% of Irish GDP.

On 19 November, Trichet wrote to Lenihan to say the ECB would not continue to augment the emergency liquidity it had been providing unless Ireland sought a rescue programme[14]. Two days later, the government gave in.

‘I would like to inform you that the Irish Government has decided today to seek access to external support from the European and international support mechanisms,’ Lenihan wrote to Trichet on 21 November. He called it a ‘grave and serious decision’[15].

The same day, the IMF said it stood ready to join in the rescue effort. EU and euro area finance ministers also put out a statement saying they were prepared to move ahead, pledging to finalise the deal in early December[16].

EU finance ministers officially approved the agreed rescue package at their 6 and 7 December meeting[17]. The package envisaged €85 billion in assistance, of which Ireland itself provided €17.5 billion. Others delivered the remaining €67.5 billion, including €17.7 billion in loans from the fledgling EFSF[18], whose board assented on 21 December following the IMF.

In exchange for international assistance, Ireland pledged to shrink its banking sector, tighten financial regulation, rein in public spending, and enact structural reforms aimed at boosting growth. Specifically, the Irish agreed to open up service sectors that had been protected, and also to pursue wage adjustments in a bid to make the country more competitive.

From the start, Irish authorities were determined to show the international community that they were serious about overhauling their economy. ‘Ireland has proved so far to be flexible and aggressive in dealing with its problems and will continue to be so,’ Lenihan said in his letter to Trichet[19].

In the days leading up to the programme, Irish officials fought hard to make sure the reforms required were things they could deliver.

‘All the incentives are to pre-negotiate as much as possible,’ said Ireland’s Cardiff, at the time one of Lenihan’s senior deputies. ‘In fairness, the other side also wanted that because the one thing no one wanted was that you’d have a promise that there would be a deal and then it couldn’t be finalised. That could be terrible.’

In the run-up to the aid negotiations, Ireland had sought to keep its distance from the IMF in order not to spook investors. It could negotiate with its euro area peers on the sidelines of regular meetings, but direct talks would have signalled that Ireland was in need of a rescue package and therefore on the brink. ‘The IMF was like a little explosive, once you introduced the name into a conversation,’ Cardiff said. If IMF officials came for a special meeting, ‘then that became a signal to the market of some sort.’

This signalling was especially significant because Ireland would become the first country to seek aid under the new EFSF firewall system. The country might have benefited from looking to outside help sooner – in 2017, an evaluation report of EFSF and ESM activities found that Ireland could have requested a programme as early as April or May 2009 – but at that time there was no euro area mechanism in place.

In Cardiff’s view, Ireland had every incentive to wait until the outlines of the deal would be clear to make its request for aid. Otherwise international officials might have pressured Ireland to make changes out of step with Irish economic priorities, Cardiff said. ‘People really want to help, but they’re also policymakers with administrations behind them, and people are saying, “We waited 10 years to have a moment when we could ask for this, that, or the other.”’

The final negotiations came down to just a few days in mid-November. As Cardiff describes it: ‘We were trying to say what would be in the programme. I remember being on the phone back to Dublin to the minister saying: “After trying hard I finally have a list. It’s not that ambitious, we might actually do more than they’re asking.” Our own list of economic conditionality was a bit bigger than the proposal.’

By this point, Regling had built the core of his firewall and was laying the groundwork for the EFSF’s financial market debut. Cardiff remembers him at a euro area finance ministers meeting just before the deal went through – present, but keeping a low profile, in conformity with the EFSF’s initial technocratic design.

Ireland proved a test case for the rescue model on a number of fronts. It faced relatively high interest rates from the EFSF because the consensus at the time was that support programmes should be a last resort to be quickly exited, and therefore made economically relatively unattractive. The IMF provides loans at shorter maturities with interest rates also geared towards encouraging programme exit. But euro area countries later twice adjusted their approach, offering in 2011 and 2013 an easing of loan terms to Ireland and Portugal, once it became clear that high borrowing costs hindered rather than helped the countries’ efforts to restore access to financial markets.

As the programme progressed, Ireland became a positive case study for the euro area model of providing conditional financial assistance to countries in need. The Irish 10-year government bond yield, which had peaked at a monthly average of 12% in July 2011, would steadily decline through 2012, giving the Irish authorities some breathing room. In the first half of 2012, the Irish debt agency resumed selling short-term paper on the financial markets. In July 2012, the Irish debt agency sold its first bond, and since then the country has made a point of rolling over existing debt and managing its budget so that it has close to a year of financing on hand at all times.

‘We wanted to deal with our own situation,’ Cardiff said. ‘There was, at that point at least, determination in the government to address the problems fully. There was no one trying to say “let’s do half a job here.”’

Wieser, former chairman of the Eurogroup Working Group, agreed that the Irish recognised that they were authors of their own misfortune. The programme largely covered the financial reforms they themselves knew needed implementing. ‘With one or two extremely important exceptions, the programme design followed very much the Irish economic policy restructuring plans, which they themselves had drawn up,’ Wieser said. ‘It is more a matter of the political system and the sociological conditions in a country whether there is the perception of being against the wall or not. If you look at the five different programme countries, in Ireland there is the highest degree of perception that they were instrumental themselves in causing this mess.’

Ownership was present in Ireland from the rescue’s beginning. The Irish Times, in an opinion piece on 18 November 2010, in the end stage of the negotiations, echoed Greek resentment at the need to request outside aid, but also recognised domestic responsibility for what had happened. ‘We have surrendered our sovereignty to the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. […] The true ignominy of our current situation is not that our sovereignty has been taken away from us, it is that we ourselves have squandered it.[…] It is the incompetence of the governments we ourselves elected that has so deeply compromised our capacity to make our own decisions’[20].

The EFSF disbursed the first tranche of €3.6 billion to Ireland at the start of February 2011. Setting a pattern for other aid recipients, Ireland made its first cautious return to market financing during its programme, in July 2012, with a 5-year bond sale that raised €500 million[21].

‘That sense of ownership was essential to Ireland’s eventual success with its programme,’ said Chief Economist Strauch. Ireland also benefited from its willingness to engage fully with the global economy, which led to a strong economic recovery once it had overcome the worst of the crisis, Strauch said, adding: ‘That’s basically because Ireland is a small, open economy. Once you’re over what was really a bubble, then you can grow fairly rapidly.’

By sticking to its economic commitments, Ireland was able to make a clean exit from its rescue programme in December 2013. A year later, it repaid the first tranche of its IMF loans ahead of schedule. By March 2015, it had completely repaid the most expensive part of its IMF assistance, roughly €18 billion in loans that had been scheduled for repayment between July 2015 and January 2021[22]. By 2018, it had repaid the IMF in full, as well as Denmark and Sweden[23].

Schäuble, the former finance minister of Germany, paid tribute to Ireland’s success. ‘Ireland has successfully downsized and consolidated its bloated banking sector and is now one of the EU’s most dynamic economies once again.’

Continue reading

[1] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2011), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Ireland’, European Economy Occasional Papers 76, p. 5, February 2011.

[2] Irish Times (2010), ‘The big gamble: The inside story of the bank guarantee’. 25 September 2010. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/the-big-gamble-the-inside-story-of-the-bank-guarantee-1.655629

[3] Ireland, Department of Finance (2010), ‘Minister’s statement on banking 30 September 2010’, 30 September 2010, Press release. https://www.finance.gov.ie/updates/ministers-statement-on-banking-30-september-2010/

[4] Irish Times (2010), ‘Anglo Irish Bank – a timeline’, 30 September 2010. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/anglo-irish-bank-a-timeline-1.864923; The Guardian (2009), ‘Anglo Irish Bank nationalised’, 15 January 2009. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/jan/15/anglo-irish-bank-nationalisation

[5] National Asset Management Agency Act 2009, 22 November 2009. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2009/act/34/enacted/en/html

[6] ECB (2008), Recommendations of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank on government guarantees for bank debt, Frankfurt, 20 October 2008. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/recommendations_on_guaranteesen.pdf

[7] Regling, K., Watson, M. (2010), A preliminary report on the sources of Ireland’s banking crisis, p. 43, Government Publications Office, Dublin. http://www.bankinginquiry.gov.ie/Preliminary%20Report%20into%20Ireland%27s%20Banking%20Crisis%2031%20May%202010.pdf

[8] BBC (2010), ‘Irish deficit balloons after new bank bail-out’, 30 September 2010. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-11441473

[9] France, Germany (2010), ‘Franco-German declaration: Statement for the France-Germany-Russia Summit’, 18 October 2010. https://www.eu.dk/~/media/files/eu/franco_german_declaration.ashx?la=da

[10] European Commission (2018), Recommendation for a Council Decision abrogating Decision 2009/414/EC on the existence of an excessive deficit in France, COM(2018) 433 final, 23 May 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/com_2018_433_en.pdf

[11] See, for example, Spiegel (2010), ‘EU agrees to Merkel’s controversial euro reforms’, 29 October 2010. http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/brussels-summit-eu-agrees-to-merkel-s-controversial-euro-reforms-a-726103.html; or Financial Times (2010), ‘Franco-German bail-out pact divides EU’, 24 October 2010. https://www.ft.com/content/56984290-df96-11df-bed9-00144feabdc0; or Brunnermeier, M., James, H., and Landau, J-P. (2016), The euro and the battle of ideas, Princeton University Press, p. 1. https://press.princeton.edu/titles/10828.html

[12] Pisani-Ferry, J. (2014), The euro crisis and its aftermath, Oxford University Press, Oxford, p. 10.

[13] Ireland, Department of Finance (2010), ‘Information note on the economic and budgetary outlook 2011-2014’, Press release, 4 November 2010. http://www.finance.gov.ie/updates/information-note-on-the-economic-and-budgetary-outlook-2011-2014-in-advance-of-publication-of-four-year-budgetary-plan/

[14] ECB (2010), Letter written by Jean-Claude Trichet to Brian Lenihan, reclassified for publication on 6 November 2014, 19 November 2010. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/shared/pdf/2010-11-19_Letter_ECB_President_to%20IE_FinMin.pdf?31295060a74c0ffe738a12cd9139f578

[15] Ireland, Department of Finance (2010), Letter written by Brian Lenihan to Jean-Claude Trichet, reclassified for publication on 6 November 2014, 21 November 2010. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/shared/pdf/2010-11-21_Letter_IE%20FinMin_to_ECB_%20President.pdf?432af7ba36b71099b55893b819ae2502

[16] Statement by the Eurogroup and Ecofin Ministers, 21 November 2010. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/117898.pdf

[17] 3054th Council meeting Economic and Financial Affairs, Press release, No. 333, 7 December 2010. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/118290.pdf

[18] Council Implementing decision on granting Union financial assistance to Ireland, Interinstitutional file, 2010/0351(NLE), 7 December 2010. http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-17211-2010-INIT/en/pdf

[19] Ireland, Department of Finance (2010), Letter written by Brian Lenihan to Jean-Claude Trichet, Reclassified for publication on 6 November 2014, 21 November 2010. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/shared/pdf/2010-11-21_Letter_IE%20FinMin_to_ECB_%20President.pdf?432af7ba36b71099b55893b819ae2502

[20] Irish Times (2010), ‘Was it for this?’, 18 November 2010. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/was-it-for-this-1.678424

[21] Ireland, National Treasury Management Agency (2012), ‘NTMA announces bond switch and outright sale’, 26 July 2012. https://www.ntma.ie/news/ntma-announces-bond-switch-and-outright-sale; for a fuller assessment of how four programme countries approached the restoration of market access, see Strauch, R., Rojas, J., O’Connor, F., Casalinho, C., de Ramón-Lapa Clausen, P., Kalozois, P. (2016), Accessing sovereign markets: The recent experiences of Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Cyprus, ESM, Discussion Paper 2, 20 June 2016. https://www.esm.europa.eu/sites/default/files/esmdp2final.pdf

[22] Ireland, National Treasury Management Agency (n.d.) ‘EU/IMF programme summary’, https://www.ntma.ie/business-areas/funding-and-debt-management/other/eu…

[23] Ireland National Treasury Management Agency (2017), ‘NTMA completes further €5.5 billion early repayment of EU/IMF programme loans’, 20 December 2017. http://www.ntma.ie/news/2017/12/20/ntma-completes-further-e5-5-billion-early-repayment-of-euimf-programme-loans/