5. Enlisting Klaus Regling: ‘I have his number’

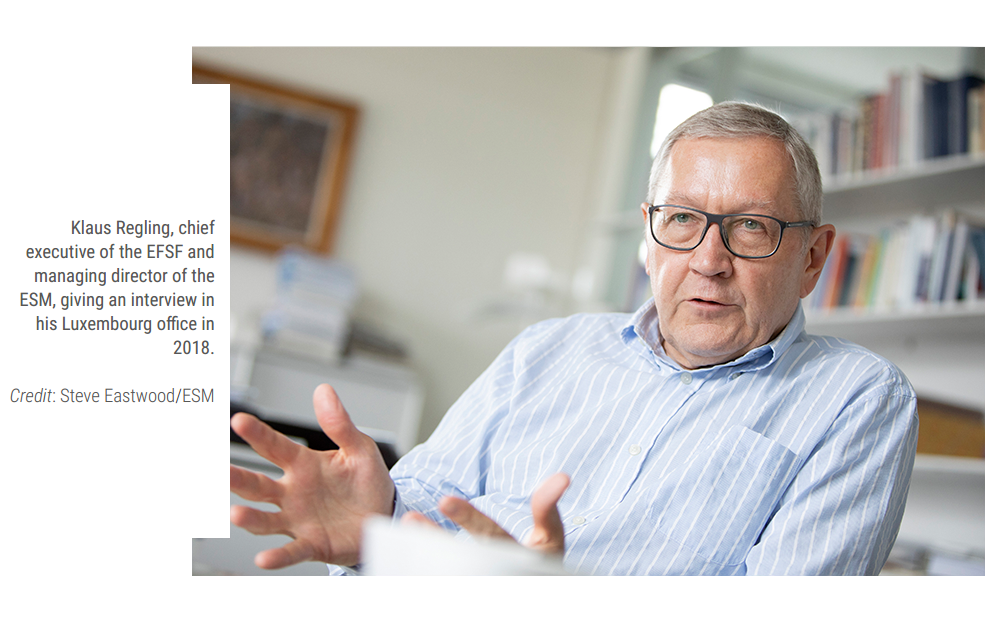

When the euro area agreed to start a rescue fund, it needed someone to run it. In June 2010, during meetings in Luxembourg, finance ministers began kicking around the names of potential candidates. Several rose to the top, but Juncker, then chief of the Eurogroup, had a clear idea about whom to recruit.

‘Klaus Regling is a leading expert in international and European finance. With him as CEO, the company’s quality and credibility were secured from the start,’ said Juncker, now European Commission president. ‘It was only natural for me to insist on his nomination.’

Behind the scenes, the recruitment process was a little bumpier. Wieser, Eurogroup Working Group chairman during the crisis, was dispatched to run the search, alongside the finance ministers of Belgium and Malta. According to Wieser, when the time came for the three initial candidates to be interviewed, Juncker was furious that Regling wasn’t on the list.

‘He said, “Why haven’t you chosen one already?”’Wieser recalled. ‘I said, “Well, first comes the closing of the call for candidates, then we arrange for interviews,” and he replied, “I’m not interested in that, I want everything to be done by tomorrow. And incidentally, I hope that Klaus Regling has been nominated by the German government.” I said, “No, Klaus is working together with Max Watson on some analysis for the Irish government, and he has not put forward an application”. Juncker was hopping mad, I’ve never seen him that way – “This is intolerable” – and then he turned to the Germans and asked, “Why the heck didn’t you propose Klaus?”’

It emerged that, on the day Wieser’s group of finance ministry deputies announced the search for chief executive candidates, the German representative hadn’t passed on the information to his home base. This oversight set off a scramble to track Regling down. ‘People were taking out their mobile phones and saying “I have his number somewhere,”’ recalled Heinrich, then a senior finance ministry official for Luxembourg.

Regling had just returned to Brussels after taking a fellowship at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore to research financial and monetary integration in Asia. From his academic perch in the tropics – and the window of his high-rise apartment – Regling had tangible evidence of how the market turmoil was affecting the world economy. ‘Every day, I saw the number of idle ships in the port increasing. World trade was coming to a standstill towards the final months of 2008. It was fascinating to see – and scary.’

As director-general for economic and financial affairs of the Commission from 2001 to 2008, Regling had become well known in every European finance ministry. In that position, he had attended all the monthly Eurogroup meetings of finance ministers, where he got to know Juncker, who started chairing the meetings in January 2005. There was an initial positive reaction from several ministers who knew Regling from this time and could vouch for his willingness to take a tough line with countries that were reluctant to follow through on their economic recommendations.

Regling had the level head and ‘sound technical understanding of what was happening’ to do the job, plus he was sufficiently accomplished in the policy arena with his Eurogroup experience, yet he wasn’t seen as a politician, Heinrich said. But he wasn’t sure Regling would want the job.

‘I had met him a few months earlier and he was all excited about his consultancy work,’ Heinrich recalled. Contacted at the last minute, Regling fortuitously happened to be in Belgium. Heinrich said that, when the EFSF call came, ‘to my surprise,’ Regling responded positively.

As a believer in the euro, Regling hoped that the proposed firewall fund would not be needed in the end, even if that meant any potential new job would be slow-paced. But he agreed to interview the next morning, and like the other candidates made his case in person. The choice was clear. ‘I reported back to a special and short Eurogroup meeting after that on the findings of the panel, which had decided on Klaus. It was incredible,’ Wieser said.

‘I never got a job so quickly,’ Regling said.

Lagarde, now IMF managing director who was French finance minister when Regling was chosen, credited ‘a fascinating combination of professional experience’ with making him perfect for the role. ‘He combines the layers of an internationally minded person, as a former IMF staff member, and a true and very deeply convinced European.’

Regling’s good relations with all of his former employers, including the IMF, the German finance ministry, and the European Commission were an essential part of how the EFSF and ESM joined an already crowded group of negotiators.

The Commission’s Angel said: ‘For some of my colleagues it was not always easy to get used to the fact that there was another player in town whose needs and views we needed to take into account. That is over now. The fact that it was Klaus helped considerably because Klaus knew everyone. He managed to have the EFSF invited into the Eurogroup Working Group of deputy finance ministers and to the Eurogroup of finance ministers immediately. I’m not sure anyone else would have secured that so easily and so quickly.’

The goodwill lasted throughout Regling’s first five-year term at the ESM, which followed his initial EFSF appointment, and has reached into a second, announced in February 2017. ‘His appointment for a second term in office was very welcome,’ said the ECB’s President Draghi. ‘His broad knowledge and experience have been very beneficial for the functioning of the ESM and cooperation with the ECB.’

Focus

A life in public service

Klaus Regling was born on 3 October 1950, in Lübeck, West Germany, right at the border with East Germany. He was the son of a master carpenter, who ran his own carpentry business and sat in the German parliament, the Bundestag, for the Social Democrats from 1953 to 1969. Politics and economic issues were the order of the day in the Regling household.

Regling studied economics in Germany, earning a bachelor’s degree from the University of Hamburg in 1971 followed by a master’s degree at the University of Regensburg in 1975. He began his professional career at the IMF in Washington DC – the start of a 40-year journey in public service that would take him around the world.

From 1980 to 1981, Regling worked for the Association of German Banks before taking up his first post at the German finance ministry, where he would remain until 1985. Then it was back to the IMF: first at the international capital markets unit in Washington, and then as the IMF representative for Indonesia in Jakarta, furnishing the start to what would become a rich experience dealing with crises.

During the 1990s, Regling rose through the ranks of Germany’s finance ministry, serving first as chief of the international monetary affairs division, and then becoming deputy director-general for international monetary and financial relations. He was a key contributor to the effort to build a European Economic and Monetary Union, experience that would stand him in good stead when the time came to build up the EFSF and ESM.

In 1995, the same year ‘euro’ was chosen as the name for the new currency, Regling became the German ministry’s director-general for European and international financial relations, taking an active role in negotiations within the EU and the Group of Seven industrialised democracies, and playing an important role in preparing for the euro’s 1 January 1999 debut.

His role meant he attended meetings of the Group of Seven countries at the height of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. This complemented his earlier IMF assignments, on which he had seen the aftermath of the mid-1980s Latin American debt crisis up close. At that time he had been involved in designing instruments – such as the Brady bonds, designed to help developing countries turn bank debt into bonds with backing from the US Treasury – and, in turn, aid banks in coping with the losses from the episode. Because of that experience and his work as an IMF representative a few years earlier, the Indonesian government invited Regling to come to Jakarta several times in 1998 – the height of the Asian crisis – to help design a solution for the public debt crisis.

To understand Regling’s thinking, it is worth looking at the Asian crisis, which he witnessed at first hand. The financial crisis offered some lessons for the EU. The three economies that were hit worst – Indonesia, South Korea, and Thailand – had continued to link their currencies to the dollar as the US currency depreciated. These export-focused east Asian economies thrived on the low dollar, but, when the currency began recovering in 1996, their competitiveness rapidly evaporated. The Asian crisis was triggered by that loss of competitiveness, aggravated by high public debt and, in some cases, by banking problems.

The crisis took off in July 1997 when Thailand allowed the baht to float because it was running out of foreign currency to defend its peg to the dollar against speculative attacks. The baht collapsed, sparking contagion across the region: Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia were caught up in the turmoil and even Singapore’s dollar began to decline. The upheaval led a spate of countries to seek support from the IMF, which in turn fostered public ire at what was perceived as harsh austerity imposed from the outside. It also prompted discussion of an Asian Monetary Fund.

An Asian Monetary Fund did not come to pass at the time. But a group of neighbouring countries did in fact turn to regional tools to address the unfolding crisis in East Asia. Before their crisis, members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and their ‘Plus Three’ partners – China (including Hong Kong), Japan, and South Korea – had already devised a series of bilateral swap arrangements as a way to address short-term dollar liquidity crunches, a small first step in creating a regional mechanism for managing a financial crisis. The Chiang Mai Initiative has since expanded into a multilateral currency swap arrangement among the participants, the so-called CMI Multilateralisation with a pool of $240 billion in foreign reserves.

The EU didn’t heed these lessons when it designed the euro, failing to pay sufficient attention to developments in competitiveness, and it had no internal buffers against capital market headwinds, Regling said. ‘We didn’t have rescue mechanisms. We needed some of these tools but they did not exist, even though the lessons might have been learned from Asia in 1997.’

As well as demonstrating how fast contagion can spread, Asia’s travails had other lessons for the EU, namely the limitations of using floating exchange rates to tackle deeper structural imbalances. ‘An exchange rate can be very useful sometimes but it can also be very risky on other occasions,’ Regling remembers. ‘Indonesia tried everything in 1997–1998 to stop the depreciation of their currency but they were not able to do so. In the end, the Indonesian rupiah depreciated by almost 90%, which meant that everybody with foreign currency debt – the sovereigns and companies – went bankrupt.’

Of course, euro area countries no longer had currencies of their own to devalue in nominal terms. Even so, real exchange rates move in a monetary union and should be monitored closely. ‘Every crisis is different, but it is good to try to remember what happened in other crises,’ Regling said.

In 1998, Germany elected a new government, leading Regling to take a break from the public sector. The incoming finance minister, Oskar Lafontaine, felt that the country’s economic difficulties were mostly due to weak demand. Regling pushed back, saying the country needed structural reforms and not just more spending. ‘After five minutes, he realised I was a hopeless case,’ Regling recalled, noting that he left the ministry on friendly terms.

Seeking a new perspective on the financial world, Regling joined a London-based hedge fund, Moore Capital Strategy Group, serving as managing director from 1999 to 2001. ‘It was a good experience, but after two years I was ready to move on,’ he said.

Opportunely, Regling’s ‘dream job’ opened up at the European Commission in Brussels. From 2001 to 2008, he served as director-general for economic and financial affairs, one of the institution’s most important civil service posts. While there, he was instrumental in implementing the new framework of oversight and guidance that came in with the common currency, and he won the lasting respect of his colleagues.

Regling left the Commission not because he was tired of his job, but because the EU’s strict institutional rules meant he could keep the same post for only seven years and he couldn’t think of anything else he’d rather do there. He accepted a year-long academic fellowship in Singapore, then returned to Europe in late 2009 to open an economic and financial consultancy in Brussels, where he was content until Europe came calling with the next opportunity.

Shortly after Regling left, the Commission produced a retrospective[1] on 10 years of the euro, and its authors awarded him a signal honour. Gaspar, former finance minister of Portugal, who was one of the co-editors alongside Buti, Regling’s successor as the Commission’s director-general for economic and financial affairs, said: ‘This book is dedicated to Klaus Regling. And that is not a coincidence.’

Continue reading

[1] European Commission (2010), The euro: The first decade, eds: Buti, M., Deroose, S., Gaspar, V., and Nogueria Martins, J., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/befd33a4-e826-4e6e-b5f5-f625fe849b7a