4. The €750 billion weekend: the EFSF is born

By the time the Greek Loan Facility was agreed, contagion – the spread of financial instability across national borders – was on everyone’s mind. The European Council President Herman Van Rompuy, the former Belgian premier who led summits of EU leaders, expressed confidence that the new programme would allow Greece ‘to put right its economic and financial situation as well as its competitiveness’[1]. But he also laid out immediate plans for reinforcement of euro area governance, announcing a summit for 7 May ‘to conclude the whole process and to draw the first conclusions of this crisis for the governance of the euro area’.

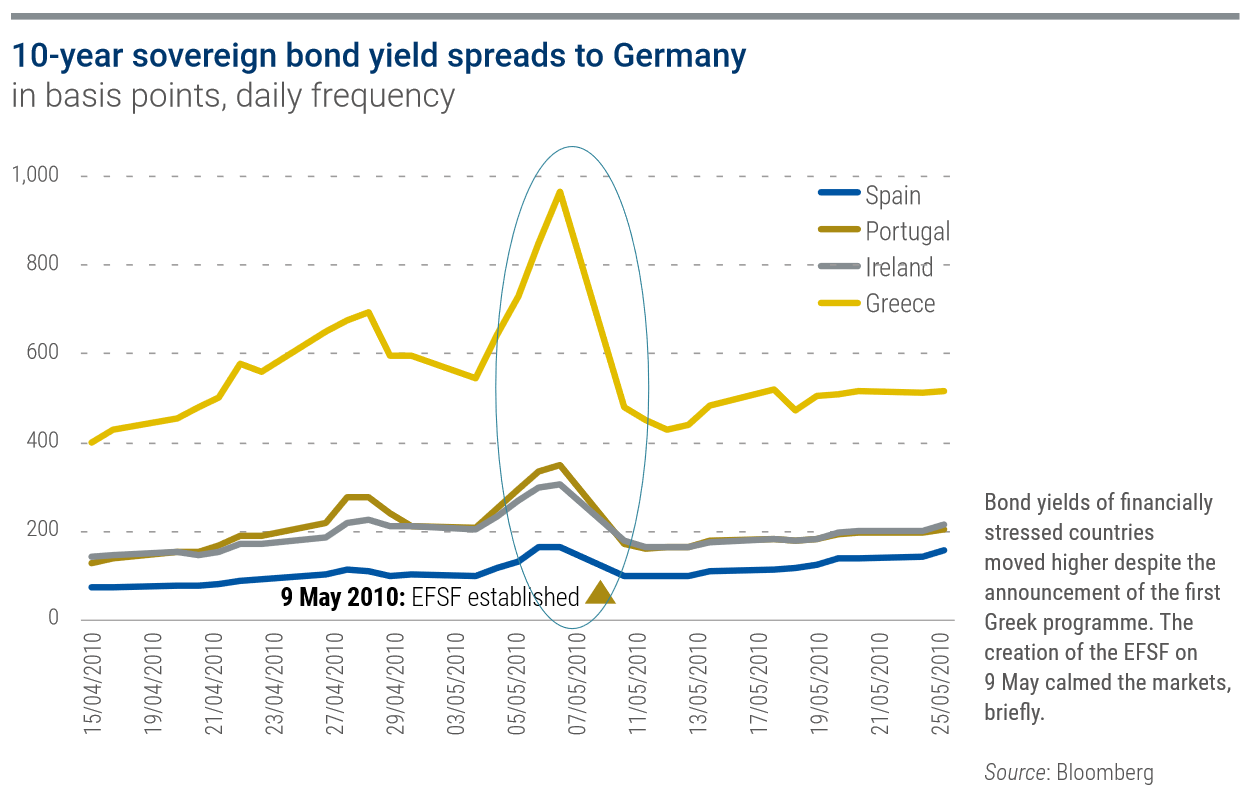

Van Rompuy’s hope to ‘conclude the whole process’ was a bit optimistic. The events of that first May weekend would instead become one of the pivotal moments in a crisis that would propel five euro area member states to seek help and force the ECB to unprecedented measures. Even before the leaders arrived in Brussels, it was clear that things were looking grim. ‘The Greek Loan Facility only calmed things for a few days in May,’ said Rehn, then the European commissioner for economic and monetary affairs and the euro. ‘Then all hell broke loose again on financial markets.’

European markets were imploding. There was almost no interbank lending, meaning the financial system’s usual ebb and flow had been replaced by huge traffic jams. The whole thing seemed on the brink of an acute crisis. ‘We had to cope with this intensification of the sovereign risk crisis in the euro area with Greece in a very dramatic situation – experiencing a sudden halt in financing. Global investors also considered that Ireland and Portugal were in situations of extreme danger and very close to a sudden stop,’ said Trichet, the ECB chief at the time.

Euro area leaders recognised that contagion threatened to undermine the common currency as a whole, but translating that insight into aid for individual countries was a fraught political enterprise. Verwey, a senior European Commission official who was with the Dutch finance ministry at the outbreak of the crisis, recalls the ‘mood music’ in the Netherlands. At the time, he said, a common attitude towards the Greeks was ‘let them sort out their own problems.’

It was a ‘very traumatic period,’ remembers Papaconstantinou, former Greek finance minister. When Greece finished negotiations for its first aid package, it had rekindled a brief feeling of hope. But then came ‘that awful week between the first bailout and the creation of the EFSF, where we all realised that we hadn’t solved the problem,’ he said.

One day before the summit, journalists had grilled Trichet over whether the euro area needed a procedure for sovereign defaults and whether the central bank would consider purchasing government bonds to prevent a financial collapse. ‘Default is out of the question. It is as simple as that,’[2] he said during the ECB’s 6 May press conference, sticking to the central bank line that forcing losses on euro area government bond investors would destroy credibility for the currency area as a whole.

When he arrived in Brussels to meet with leaders, a pivotal moment approached. ‘It was Friday afternoon, very dramatic,’ Trichet recalled. ‘I did not hesitate to say that we had a dramatic situation in several countries in the euro area, as well as in the euro area itself. I had stressed the gravity of this situation every month since 2005 in the Eurogroup.’

Arguing that the euro area’s persistent divergences in labour costs, productivity, and competitiveness were a recipe for catastrophe, the central banker called on the leaders to set up new frameworks for the monitoring, governance, and bulwarking of the common currency. As Trichet made the case that Europe had an obligation to put its economic house in order, the leaders initially resisted. But Trichet pressed his point: ‘I was very, very strong.’

By the end of the evening, the euro area leaders had come around. As midnight closed in, the leaders agreed that Greece would receive the first cash infusion from its new rescue programme by 19 May. And they acknowledged that the problem went beyond Greece and would require a much broader approach. The 7 May statement called for stronger financial regulation and supervision, particularly regarding derivatives and ratings agencies. The leaders also pledged to ‘broaden and strengthen economic surveillance and policy coordination in the euro area’[3], by watching debt levels and structural measures that influence competitiveness, with stronger rules and tougher sanctions for those that didn’t keep up. Finally, they agreed to ‘create a robust framework for crisis management, respecting the principle of member states’ own budgetary responsibility.’

This new crisis-fighting framework would require a central anchor, of which the leaders had only a hazy idea at first. But they knew something had to happen by the Monday morning Asian market opening. They gave the Commission and the euro area finance ministers a very short timeline to come up with the details. ‘Taking into account the exceptional circumstances, the Commission will propose a European stabilisation mechanism to preserve financial stability in Europe,’ the leaders said in the statement, adding that euro area finance ministers would consider this proposal two days later, on Sunday 9 May.

That put the Commission in the crosshairs. While Barroso, the Commission’s president, was attending the leaders’ summit in Brussels’ blocky, brown Justus Lipsius building, on the other side of the Rue de la Loi, Rehn and his team were at work in the Berlaymont, the EU executive branch’s glass and steel headquarters.

‘The euro zone summit was on Friday and we had been preparing for it the entire week in the Berlaymont building,’ Rehn recalled. ‘We knew only very late that Friday night that we had a mandate from the euro area summit – not a very specific mandate – to come up with a proposal for a European stability fund by Sunday. So I had a brief sleep, took a quick shower, went back to Berlaymont early on Saturday morning and started to work with my team. We began looking at what policy initiatives could be economically viable and politically palatable in this dangerous situation.’

For the Commission’s Benjamin Angel, then a head of unit in the economic and financial affairs directorate-general, there wasn’t even time for a nap. ‘On Friday evening, it was just before midnight and I was about to go to bed. Instead, my director-general called me and told me to go immediately to the Berlaymont. So I got dressed, went to the Berlaymont, and met until more or less 1.30 with my director-general, the secretary-general of the Commission, the director-general of the legal service, and the head of cabinet of the president’s office. We needed to launch an initiative.’

Rehn was keenly aware of the political constraints that would shape any technical solution on offer. The summit statement was ambiguous on whether the crisis-fighting framework would be housed within the EU institutions or set up as an intergovernmental arrangement among euro area member states. The French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, and the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, had clearly reached some sort of understanding on what would be possible, but they hadn’t shared publicly how far their governments were ready to go. ‘We did not know what could have been agreed, or had been agreed, between Germany and France on the scale and size of the future fund,’ Rehn said. ‘We didn’t know, and we couldn’t find out.’

In the end, Rehn and his team didn’t want to put the matter entirely in the hands of the member states from the outset, so they decided to look for a ‘community method’ solution that would make use of the EU budget framework. ‘It was a very short proposal in the end, although it required a lot of work,’ Rehn said. Angel worked into the morning for four hours, from 2.00 until 6.00, on the proposal for a Commission emergency fund backed by the EU budget, which would become the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM)[4]. He went to bed and on Saturday met briefly with Rehn and other colleagues. By Sunday, the Commission was braced to move ahead with the EFSM proposal while the finance ministers gathered for the bruising political battle to follow[5].

Angel remembers the Commission’s top officials holding a longer-than-expected Sunday morning meeting before approving the draft, while the finance ministers were already waiting in the Justus Lipsius building for the negotiations to start on a text that no one had yet seen. ‘It was really a unique situation,’ he said.

The Sunday night finance ministers’ meeting, chaired by Spain’s Elena Salgado, turned into an all-nighter as Europe raced to put a firewall together before Monday morning trading began in Asia. As it turned out, the Commission’s proposed EFSM vehicle, which Angel had drafted in the wee hours of Saturday morning, would not be enough on its own. A second marathon effort would be needed.

‘I remember the night when the decision was reached to set up the EFSF,’ recalled Wieser, former chairman of the Eurogroup Working Group. ‘It was the night when German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble fell ill when landing in Brussels on the aeroplane, so his deputy Jörg Asmussen had to step in until they could fly in the Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière. On the sidelines, again and again, I saw Christine Lagarde, then the French finance minister, standing by the window on the phone, and Asmussen on the phone as well, and there were interventions by the US president to both the French and the German leaders that night.’

As French finance minister, Lagarde was braced for the fight. She had been trying to enjoy a weekend break with her family at her country home in Normandy, but that was not to be. ‘That Saturday pretty much all day long we had conversations with Wolfgang Schäuble, Olli Rehn, and Jean-Claude Trichet,’ she said. ‘It was supposed to have been a family weekend and there was no family time at all. And eventually, a decision was made. We all had to get together in Brussels on Sunday.’

So Lagarde threw on her suede jacket and took off for Brussels. The other players also began to gather. With Schäuble heading to hospital instead of the meeting, his deputy, Asmussen, was stalling for time until reinforcements could arrive: de Maizière, a close ally of Merkel. From Athens, Finance Minister Papaconstantinou also got the call. For once, Greece was not centre stage, having finished talks on its own programme a week earlier. The threat was clear, even if the solution was not. ‘Everybody realises you cannot have another Greek Loan Facility. So you cannot have coordinated bilateral loans. You need an instrument,’ Papaconstantinou said. ‘But nobody’s ready to create a fully fledged permanent ESM yet. We’re not there.’

Despite the sense of impending doom, the deal was not coming together. The Commission’s full plan for the EFSM ran aground when it went before the finance ministers on Sunday, on objections from Germany and other fiscally conservative states. As originally designed, it had two elements. Under the first rung of the plan, the EU would be able to borrow on financial markets, up to a limit determined by the bloc’s budget payment ceilings. That turned out to be about €60 billion and required the assent of all EU Member States, including countries outside the euro area.

Since €60 billion wasn’t going to build a firewall on the scale required, the Commission also proposed a second rung. When triggered, the Commission would still borrow on financial markets, but with direct guarantees from Member States instead of the EU budget. This was a tricky sell to the Council’s legal service, which almost immediately called for separating this second leg from the first and creating it outside the EU framework on the basis of an intergovernmental agreement.

‘Then the discussion became instantly extremely messy,’ Angel said. Germany and like-minded countries were backing a bilateral loan arrangement instead of the second EFSM tier, but other countries didn’t want a repeat of the Greek Loan Facility’s complexities. The Commission suggested an intergovernmental framework to provide guarantees to the Commission, but the Germans weren’t having it. ‘We were completely blocked,’ he said. The Germans, Angel recalls, saw difficulties with the Commission’s role, an erosion of trust in its ability to enforce strict rules.

Rehn said he met with Barroso and his economic advisor on Saturday afternoon and Sunday morning to discuss the options. ‘Based on our teamwork, I proposed we would present a combination of (a) using the EU budget as collateral to the own resources ceiling, which gave €60 billion, and (b) beyond that, as needed and separately decided, asking the EU/euro area member states to provide joint and several guarantees to the EFSM.’ He added: ‘The latter part was regarded as a critical element to create a truly convincing “big bazooka”. Yes, it would have created eurobonds of some sort. Barroso first, and then after a lengthy debate, the commissioners endorsed the proposal on Sunday. However, the finance ministers did not endorse the latter part.’

With agreement on only the smaller component of the EFSM plan, talks were stalled. Rehn said he made a last-ditch proposal, offering to let the countries choose between guarantees and bilateral loans. But no luck. ‘Nothing seemed to fly that night, so we were fairly desperate and looking for some way out,’ Rehn said. ‘We had to have a convincing solution – or at least a convincing-looking solution – before those Asian markets opened.’

At this point, Lagarde told colleagues that they still had time, but not much. The Asian stock markets would be opening in quick succession soon and she warned that it was important to reach an agreement; they could not afford to throw in the towel. She predicted havoc in the markets if the EU was not able to come up with a convincing rescue package. She appealed for ministers to stay at least another 30 minutes: ‘I was constantly watching the opening of the Sydney stock market, then the Tokyo stock market. I mean, the clock was ticking.’

Verwey, who was mentally running through possible options for a firewall, in his capacity as chairman of the Task Force on Coordinated Action, also remembers asking Asmussen what the key concern was. ‘The problem was not the guarantee instrument,’ Verwey recalled. ‘The point was that Germany didn’t want to guarantee the Commission, because for them this was a big shift in the institutional balance between the Commission and the Council. The real question was: who controls the mechanism?’

As the clock ran out, Rehn called Verwey to a meeting. Midnight had already passed, but there was still no solution for setting up a new crisis mechanism. Besides Rehn and Verwey, only a few Commission staff were in the room. ‘We brainstormed. Why was it stuck and how could we solve that? Then I came up with the idea: why don’t we set up a special purpose vehicle? They liked the idea,’ said Verwey.

Rehn said he asked Verwey to check with the German delegation, if this would be okay for them. Verwey went, returning quickly with an affirmative from de Maizière, which ended the deadlock.

The special purpose vehicle concept was well suited to assuage the concerns of the fiscally more conservative countries that had come up during the debate, as a special purpose vehicle is usually created to solve targeted, and temporary, problems. It offered the added benefit of being relatively easy to set up and get running. Not only would it be out of the Commission’s hands, it had a three-year time limit. It also bore no resemblance to anything that would sell common euro area debt, which was taboo for many countries. Instead, liability would be shared on a proportional basis among the euro countries.

For the rest of the euro area, the appeal was that the bigger rescue mechanism came with a guarantee system. The key feature was that the member states would guarantee not the loans to the programme countries, just the bonds sold on the market to finance them. This was particularly important for those economies that were themselves having problems accessing capital in the markets; they didn’t want to be too closely linked to countries in worse shape than they were. They wanted to support the new framework with less damage to their own budget and debt statistics, and they wanted a system that they might actually be able to use if the contagion came their way.

Although the Commission backed the idea, its representatives were reluctant to present it to the Germans, given the evening’s dynamic. So Verwey went instead. ‘I asked them: ‘Would you be able to accept this?’ They did, and this then became the EFSF.’

Looking back, Commission President Juncker called the decision ‘historic’, adding: ‘Thanks to the political courage and ingenuity of a few of the people present, we took bold steps to defend the stability of the euro.’

It was a momentous achievement for the euro area, and for its leaders. Lagarde, recalling the early morning press conference that followed, said: ‘We were all completely shattered, and probably looked terrible, but we were so proud to announce that we had finally put this thing to bed.’

For Schäuble, the creation of the EFSF, as a forerunner of the ESM, was proof that despite differences of opinion the euro area could act when it needed to and display solidarity, if there was the necessary conditionality. ‘That is very encouraging. All those involved were willing to work on reaching compromises that were necessary and in everyone’s interest.’

At this point, the official plan was still that the firewall would never be used. It would just be put in place, and put in place quickly, to calm the markets.

The next question for the new fund was: how big? Wieser felt the number had to be hefty enough to impress the markets or they would never calm down. ‘I figured that €200 billion would be enough, but I also figured that certain member states would bargain me down by 50%, so I put in €400 billion. To my surprise, nobody bargained it down,’ Wieser said. ‘Then in order to make it a round figure, with the EFSM at €60 billion, we just tacked on another €40 billion to the EFSF, and that’s how the €440 billion of the EFSF came into existence. It was not by design, it was a mixture of arithmetic and accident.’

At the end of that overnight marathon, the EU ministers announced that they had approved a total €500 billion euro area rescue fund. This would include a rapid-reaction EFSM of €60 billion and a special purpose vehicle that the euro area member states would guarantee. The vehicle would have a volume of up to €440 billion and would expire after three years, according to the finance ministers’ statement of 9 and 10 May 2010[6].

With some diplomatic finesse, the euro area managed to convince the financial markets that it had an even bigger bazooka because the IMF would kick in another €250 billion. The IMF never put such a specific figure on it publicly, but its then-Managing Director Strauss-Kahn indicated as much after the meeting.

‘The IMF will play its part, in the interests of the international community, in addressing the current challenges. In particular, we stand ready to support our European members’ individual adjustment and recovery programmes through the design and monitoring of economic measures as well as through financial assistance, when requested,’ Strauss-Kahn said. ‘Our contribution will be on a country-by-country basis, through the whole range of instruments we already have at our disposal. We expect our financial assistance to be broadly in proportion to our recent European arrangements’[7]. In that ballpark, the EU figured it could count on the IMF to pick up roughly a third of any new programme, with the other two thirds coming from the new firewall.

In this way, the €750 billion first bulwark came into existence. The headline figure helped calm markets. To quell uneasiness at the EU level, the Commission still had a €50 billion balance-of-payments mechanism, available to help distressed non-euro countries, such as Latvia, Hungary, and Romania, with funds raised using the EU budget as collateral. Combined with the EFSM’s €60 billion, a total of €110 billion in rescue financing was possible through Commission-administered funds – a point emphasised in communications with the European Parliament, which kept a close eye on euro area doings while representing the entire EU. The EU’s entire budget for 2010 was an only slightly larger €122.9 billion, but the rescue mechanisms wouldn’t touch that[8].

Central bankers and finance ministers around the world had been watching the EU’s sleepless Sunday night. As the talks dragged on, there was a simultaneous conference call of finance ministers and central bankers from the Group of Seven major countries. And in Washington the IMF was on full alert.

‘We were on the phone in Washington with the staff. This all was happening in the context of an endless conference call that went on for hours, and hours, and hours, between Brussels, the central bankers in Basel, plus participants in Washington, and who knows where else,’ said the IMF’s Lipsky, at the time Strauss-Kahn’s number two. ‘At least something concrete finally was agreed. The EFSF was announced only after markets had already opened in Asia. And, the ECB was ready to act in markets immediately, if needed.’

The euro area’s cash could now be counted on. And although the permanent ESM didn’t yet exist, its foundation had been laid. ‘When the EFSF was founded on 9 May 2010, it was already clear to everyone that a European crisis mechanism could not, in the long term, be based on a guarantee-backed special purpose vehicle headquartered in Luxembourg,’ Schäuble said. ‘Nobody denied the need for a European crisis mechanism based on international law.’

Focus

The European Central Bank steps up

To give the new euro firewall time to get started, the ECB provided some much-needed breathing room. With the Securities Markets Programme, in operation through September 2012, the ECB aimed to preserve liquidity in euro area public and private sector markets through bond purchases[9]. Under the programme, the ECB bought government bonds of Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, and Portugal. The scheme would improve the performance of malfunctioning segments of the euro area debt securities markets.

Shortly before the press conference announcing the new EFSF firewall, Rehn let the cat out of the bag that the ECB was moving simultaneously to reassure markets. Rehn had been told that the ECB would go public at midnight. So, thinking the ECB had already announced the move, he confirmed the action to the Financial Times Deutschland. ‘I thought that, because it was 1.30 or 2.00 and I didn’t want to look stupid, I said: “Yes, I’m aware the ECB has been acting.” Because I was told they would go public at midnight,’ Rehn said. ‘So I revealed their Securities Markets Programme scheme, because I mistakenly thought they had already gone out, and also because I instinctively wanted to give the correct impression that the euro area now had a big bazooka to contain contagion in the financial markets. But they only did so later.’

The ECB’s goal was to preserve financial stability by heading off breakdowns in trading and to strengthen the monetary policy transmission mechanism[10]. Some countries, however, were concerned that such operations could spark inflation by loosening the central bank’s monetary policy stance. To prevent this, the impact of all operations was sterilised with technical measures that re-absorbed liquidity.

‘I had enormous resistance from the governments on direct intervention in the secondary market, which was the only way to deter speculation,’ said Trichet. ‘We had the capacity to intervene immediately and the governments had to set up their own capacity.’

Continue reading

[1] Statement by President Van Rompuy following the Eurogroup agreement on Greece, PCE 80/10, 2 May 2010. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/114128.pdf

[2] ECB (2010), ‘Introductory statement with Q&A’, Transcript, 6 May 2010. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2010/html/is100506.en.html

[3] Statement by the Heads of State or Government of the euro area, PCE 86/10, 7 May 2010. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/27818/114296.pdf

[4] Council Regulation (EU) No 407/2010 of 11 May 2010 establishing a European financial stabilisation mechanism, OJ L118/1, 11 May 2010. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1484663483987&uri=CELEX:32010R0407

[5] Extraordinary Council meeting (2010), Press release, 9 and 10 May 2010. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/114324.pdf

[6] Ibid.

[7] IMF (2010), ‘Agreed EU support model boosts confidence, says IMF’, 11 May 2010. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2010/NEW051110A.htm/external/comments/index.aspx?type=rea

[8] European Commission (2009), ‘EU Budget 2010: investing to restore jobs and growth’, Press release, 17 December 2009. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-09-1958_en.htm?locale=en

[9] ECB (2010), ‘ECB decides on measures to address severe tensions in financial markets’, Press release, 10 May 2010. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2010/html/pr100510.en.html

[10] ECB (n.d.), ‘Asset purchase programmes’, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omt/html/index.en.html