ESM

The recent economic and financial crisis led many households and companies to default on bank loans. European banks carry this large stock of NPLs on their balance sheets – the single largest legacy of the past crisis. The NPLs lock banks’ potential lending capacity. During the euro area crisis, the stock of NPLs increased by more than 300% to €928 billion as of end-September 2015 from €292 billion as of end-December 2007.

NPLs are distributed unevenly across the euro area, with banks in crisis-hit periphery countries[1] holding more than two thirds of the total for the euro area as a whole. The proportion of bank capital that NPLs absorb rose to 8.1% as of end-September 2015 from 1.6% as of end-2007. At the beginning of the financial crisis, NPLs absorbed roughly the same proportion of banks’ capital in both groups of countries (1.6%). By end-September 2015, however, this ratio had climbed to 14% in the peripheral countries versus a more limited 4% in the core countries. Different NPL dynamics explain in part why the banks in the two regions reported diverging profitability during the crisis.

While the stock of NPLs remains high, the inflow of new NPLs has nearly ceased and provision coverage has risen further. As the NPL provision coverage of 52% at the system level is broadly adequate now, loan loss provisions have started declining and will drag less on profits going forward. For the banks with lower provision coverage, however, the loan loss provisions are likely to decline at a slower pace, hurting profits.

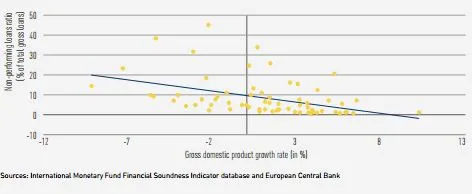

In the literature, GDP growth emerges as a driver of banks’ asset quality and it acts through various channels.[2] Recessions slow consumption, which leads to deteriorating incomes for firms, often putting them under financial pressure and reducing their capacity to repay (Figure 22). In Portugal, for example, about 30% of small- and medium-sized enterprises currently have at least one loan that is not performing. Also, in downturns, unemployment increases, forcing households to default on their loans. Whereas asset quality in mortgages is usually better because of the collateral, consumer credit is frequently in default.

The level of NPLs in the banking sector has an important bearing on credit extension and bank profits going forward. The literature shows that higher levels of capitalisation support lending to the economy, but only if NPL levels sink below a certain threshold. With NPLs under control, banks can refocus on lending activity rather than on dealing with the legacy.

Relying solely on GDP growth will not lead to a sufficiently fast decline of NPLs, as other institutional factors are equally relevant. Banks need to use the full range of NPL management tools to achieve a significant and swift reduction. In particular, insolvency frameworks should give them sufficient powers and incentives to come to a rapid solution in cooperation with borrowers. Beyond this, insolvency frameworks should also aim at simplifying and speeding up out-of-court restructurings to help preserve as much economic value as possible. A market for NPLs, including the use of professional restructuring servicers, can also help an economy take care of legacy assets. The programme countries have implemented many such legal changes and efforts should continue. Solving the NPL problem would help banks to restore a level playing field between the core and the periphery. However, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, because: the problem is unevenly distributed among countries; the composition and size of impaired loan portfolios differ; and countries have very different legal frameworks and insolvency procedures.

NPLs are distributed unevenly across the euro area, with banks in crisis-hit periphery countries[1] holding more than two thirds of the total for the euro area as a whole. The proportion of bank capital that NPLs absorb rose to 8.1% as of end-September 2015 from 1.6% as of end-2007. At the beginning of the financial crisis, NPLs absorbed roughly the same proportion of banks’ capital in both groups of countries (1.6%). By end-September 2015, however, this ratio had climbed to 14% in the peripheral countries versus a more limited 4% in the core countries. Different NPL dynamics explain in part why the banks in the two regions reported diverging profitability during the crisis.

While the stock of NPLs remains high, the inflow of new NPLs has nearly ceased and provision coverage has risen further. As the NPL provision coverage of 52% at the system level is broadly adequate now, loan loss provisions have started declining and will drag less on profits going forward. For the banks with lower provision coverage, however, the loan loss provisions are likely to decline at a slower pace, hurting profits.

In the literature, GDP growth emerges as a driver of banks’ asset quality and it acts through various channels.[2] Recessions slow consumption, which leads to deteriorating incomes for firms, often putting them under financial pressure and reducing their capacity to repay (Figure 22). In Portugal, for example, about 30% of small- and medium-sized enterprises currently have at least one loan that is not performing. Also, in downturns, unemployment increases, forcing households to default on their loans. Whereas asset quality in mortgages is usually better because of the collateral, consumer credit is frequently in default.

The level of NPLs in the banking sector has an important bearing on credit extension and bank profits going forward. The literature shows that higher levels of capitalisation support lending to the economy, but only if NPL levels sink below a certain threshold. With NPLs under control, banks can refocus on lending activity rather than on dealing with the legacy.

Relying solely on GDP growth will not lead to a sufficiently fast decline of NPLs, as other institutional factors are equally relevant. Banks need to use the full range of NPL management tools to achieve a significant and swift reduction. In particular, insolvency frameworks should give them sufficient powers and incentives to come to a rapid solution in cooperation with borrowers. Beyond this, insolvency frameworks should also aim at simplifying and speeding up out-of-court restructurings to help preserve as much economic value as possible. A market for NPLs, including the use of professional restructuring servicers, can also help an economy take care of legacy assets. The programme countries have implemented many such legal changes and efforts should continue. Solving the NPL problem would help banks to restore a level playing field between the core and the periphery. However, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, because: the problem is unevenly distributed among countries; the composition and size of impaired loan portfolios differ; and countries have very different legal frameworks and insolvency procedures.

[1] Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal, and Slovenia.

[2] See for example Glen, J. and Mondragon-Velez, C. (2011), “Business Cycle Effects on Commercial Bank Loan Portfolio Performance in Developing Economies”, International Finance Corporation, January 2011. See also: Ayar et al. (2015), “A Strategy for Resolving Europe’s Problem Loans”, IMF Staff discussion Note SDN/15/19.