Greek programme achievements

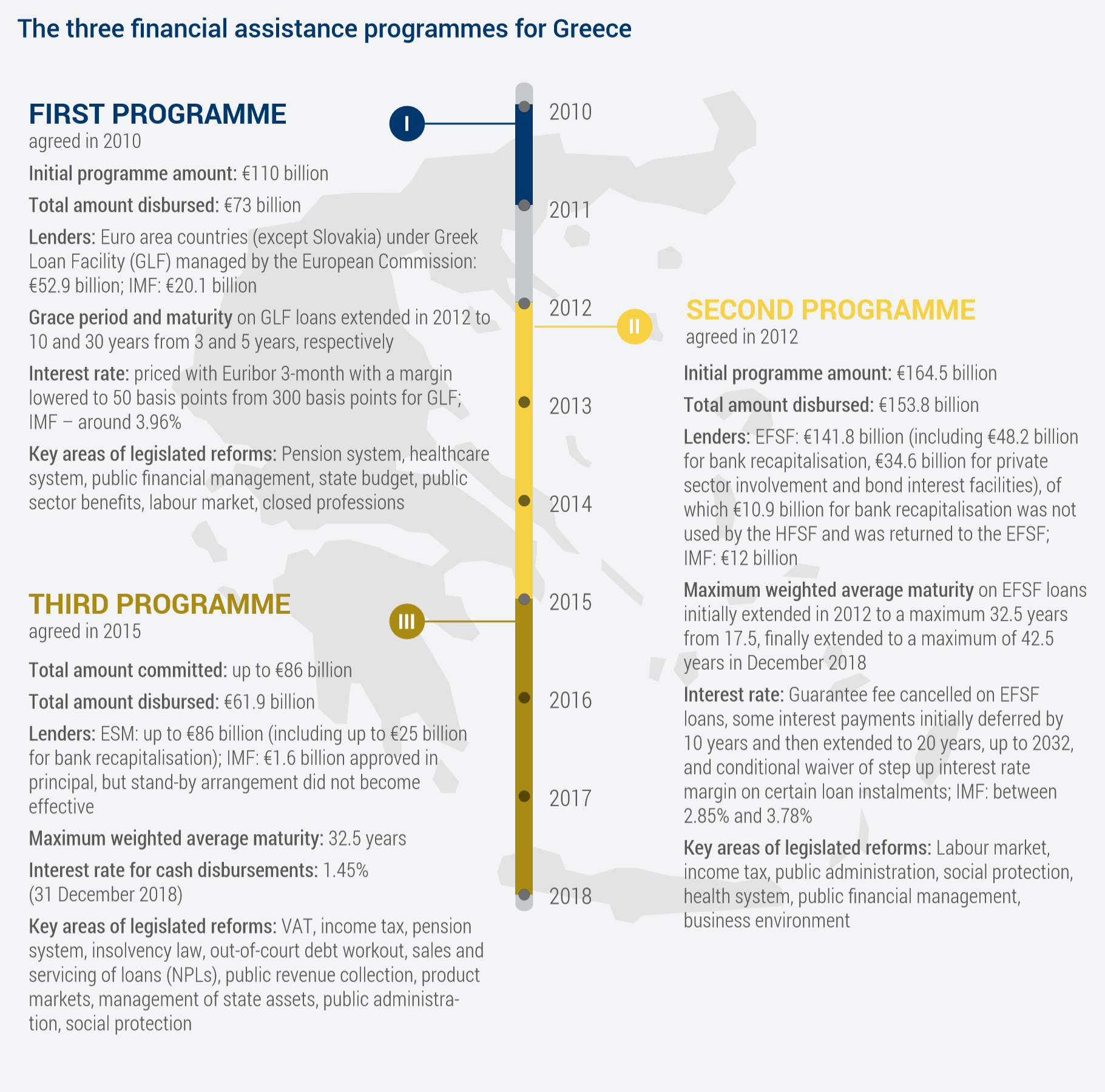

In August 2018, Greece exited its third financial assistance programme after a decade of adjustment. During these years, Greece implemented substantial reforms to restore sustainability to public finances, strengthen the banking sector’s resilience, and improve the economy’s competitiveness. During this time, Greece received almost €290 billion in official sector financial assistance and extensive debt relief. To enhance Greece’s long-term growth potential as well as to protect European partners’ large exposure, key programme reform successes must be preserved and prudent policies pursued. Greece’s still existing vulnerabilities and challenging reform targets will require closer post-programme country monitoring than the other euro area post-programme countries for some time.

What has been achieved?

Greece reduced its macroeconomic imbalances after broad-based, in-depth reforms over a decade.

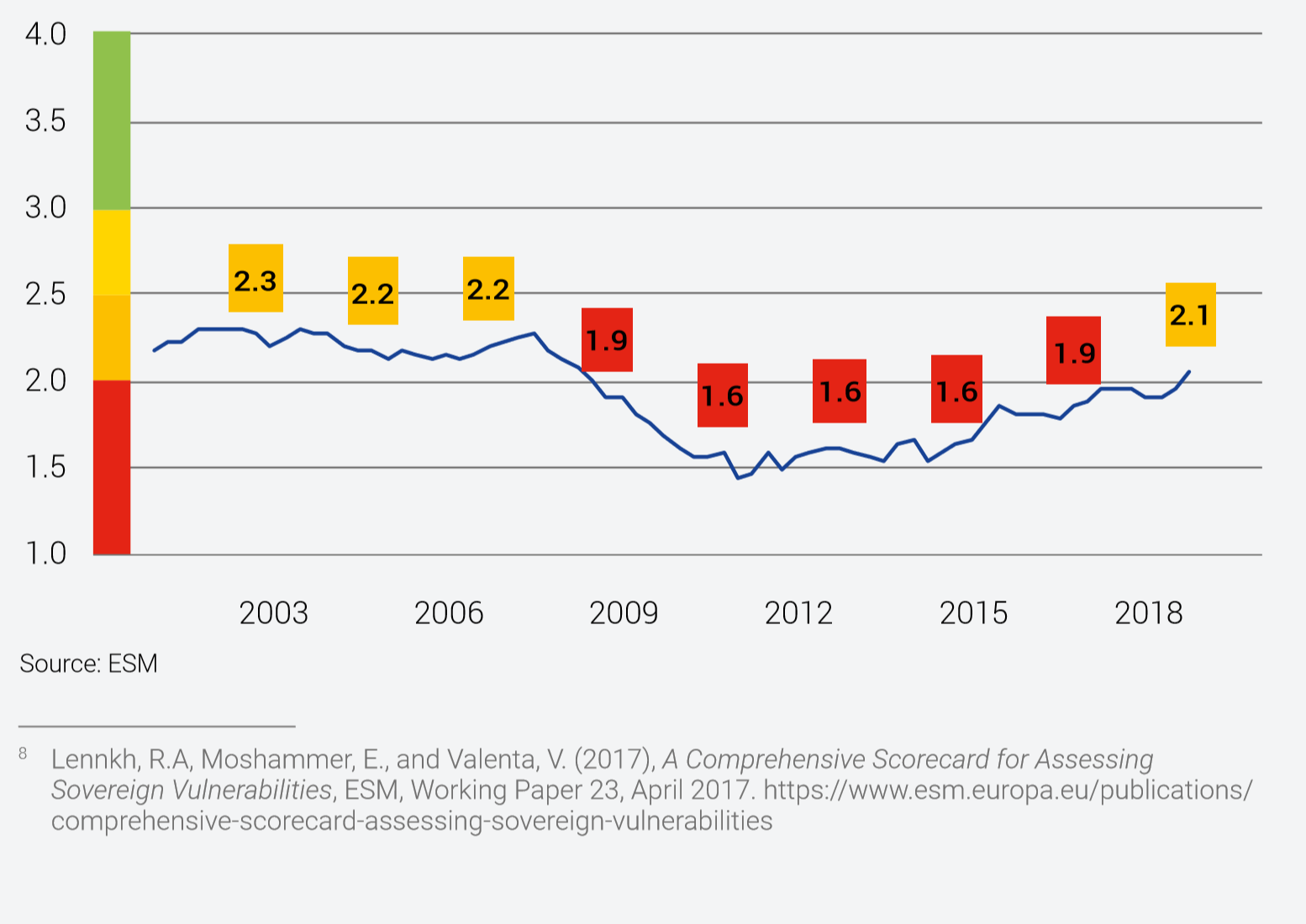

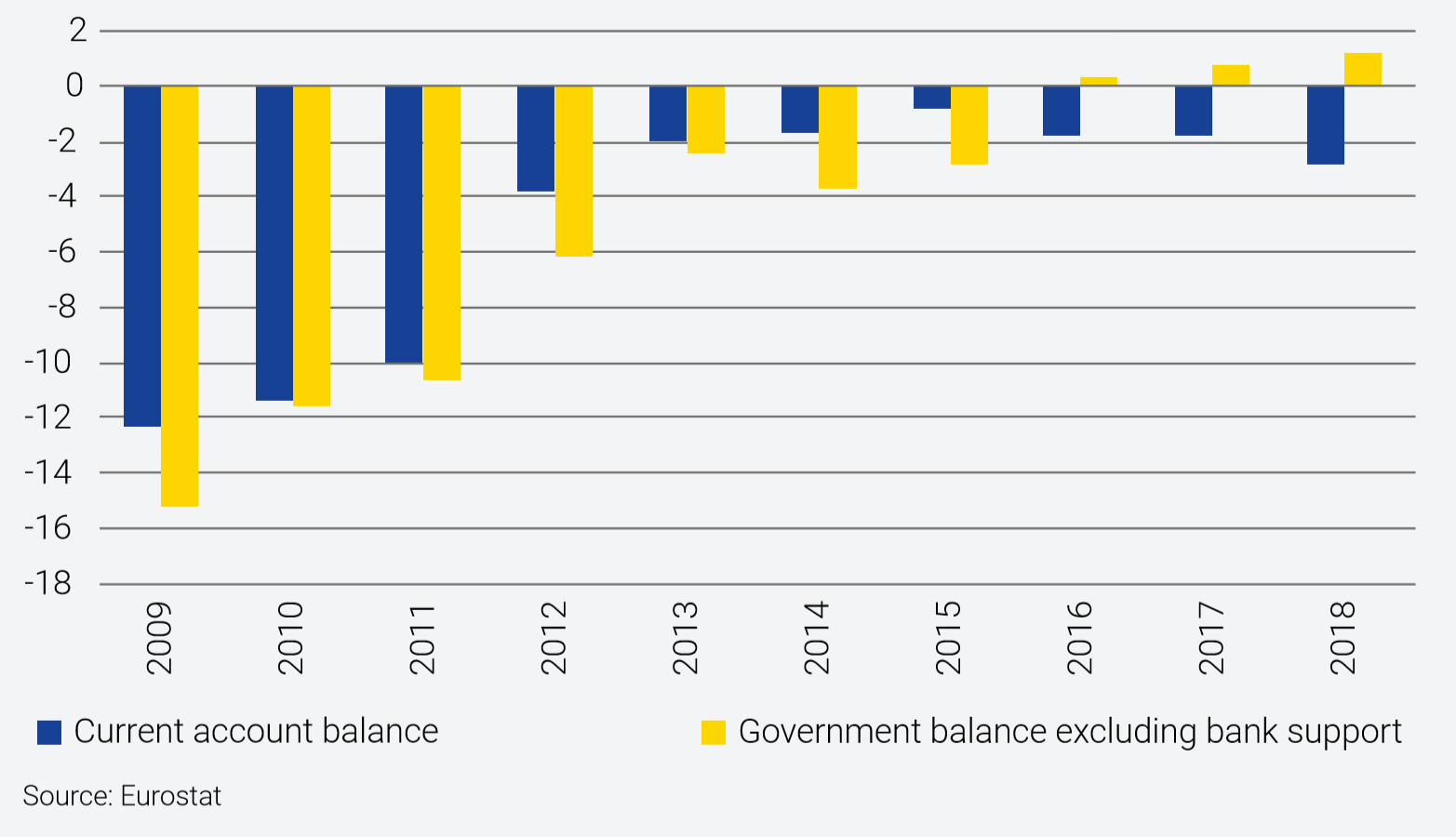

According to the ESM Sovereign Vulnerability Index[1], Greece’s vulnerabilities have declined substantially since 2009, when the current account deficit exceeded 12% of GDP and the fiscal deficit 15% of GDP (Figure 14). During the adjustment years, Greece steered its economy to safer waters by improving fiscal and external balances, reducing labour costs, and making the banking sector more resilient (Figure 15).

Figure 14: Evolution of the vulnerability score

Figure 15: Greece: Improvement of fiscal and external balance

(in % of GDP)

(in % of GDP)

Fiscal consolidation paved the way to a balanced budget.

The government fiscal balance vastly improved from a 15.1% of GDP deficit in 2009 to surpluses since 2016. Greece’s fiscal consolidation built upon a policy mix affecting both expenditures and revenues, notably through a series of reforms:

- Personal income tax: Harmonised and broadened tax base, integrated the solidarity surcharge into the personal income tax, and adjusted the tax rates over income groups with increasing progressivity. Further widening of the tax base and reduction of tax rates is legislated for 2020.

- VAT: Widened the base for the standard tax rate, increased tax rates, and limited reduced VAT regimes.

- Pensions: Lowered main and auxiliary pensions, streamlined eligibility criteria, and harmonised benefit and contribution rules.

- Public administration: Reduced public sector employment, wage and non-wage benefits for public servants, and rationalised the fragmented special wage grids.

- Revenue administration: Established an Independent Authority of Public Revenue, improved tax collection by optimising tax audits, promoting and facilitating the use of electronic payments, and reducing corruption.

- Health system: Rationalised all off-patent drug prices, provided a claw-back mechanism for pharmaceuticals, and required diagnostic and private clinics to comply with spending ceilings.

Labour costs decreased and the country’s wage competitiveness improved.

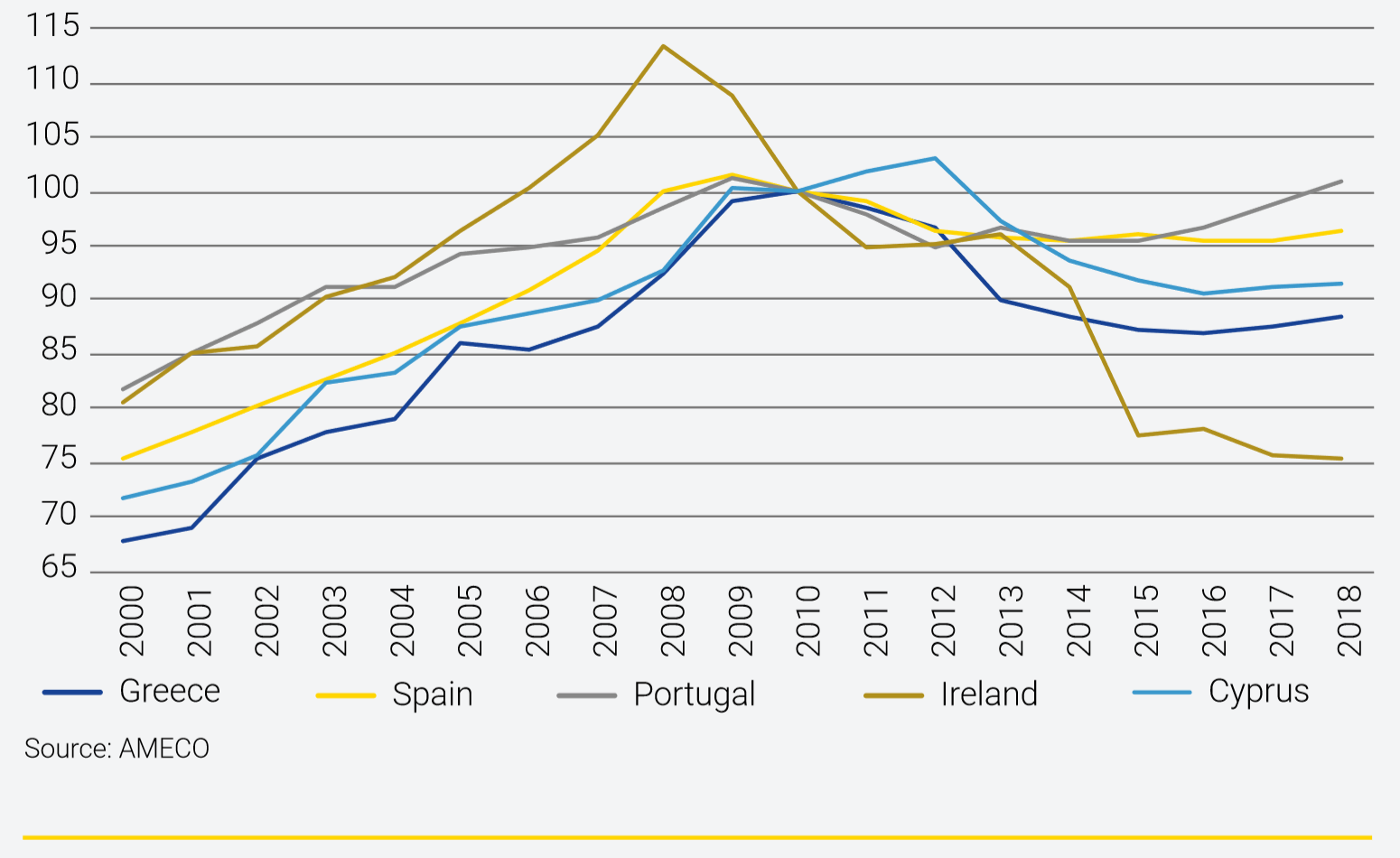

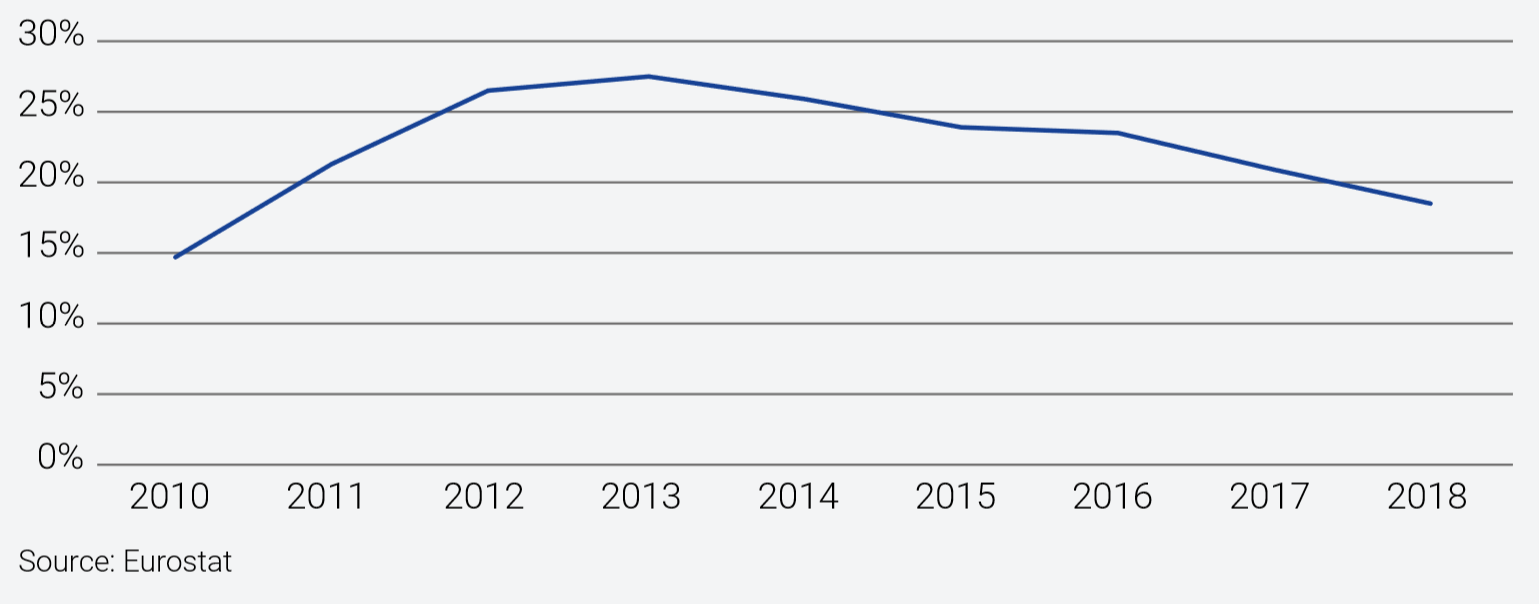

Labour market reforms – implemented mainly from 2010 to 2014 – reduced labour costs, removed rigidities, and introduced more flexible wage bargaining schemes (Figure 16). Further efforts helped to safeguard the opening clause in collective bargaining, allowing for rationalisation of the legal framework on dismissals and industrial action, tackling undeclared work, and strengthening active labour market policies. These reforms have contributed to job creation in recent years, reducing the unemployment rate from its peak of 27.8% in 2013 to 18.4% at end-2018 (Figure 17).

Figure 16: Nominal unit labour costs

(2010=100)

(2010=100)

Figure 17: Unemployment rate

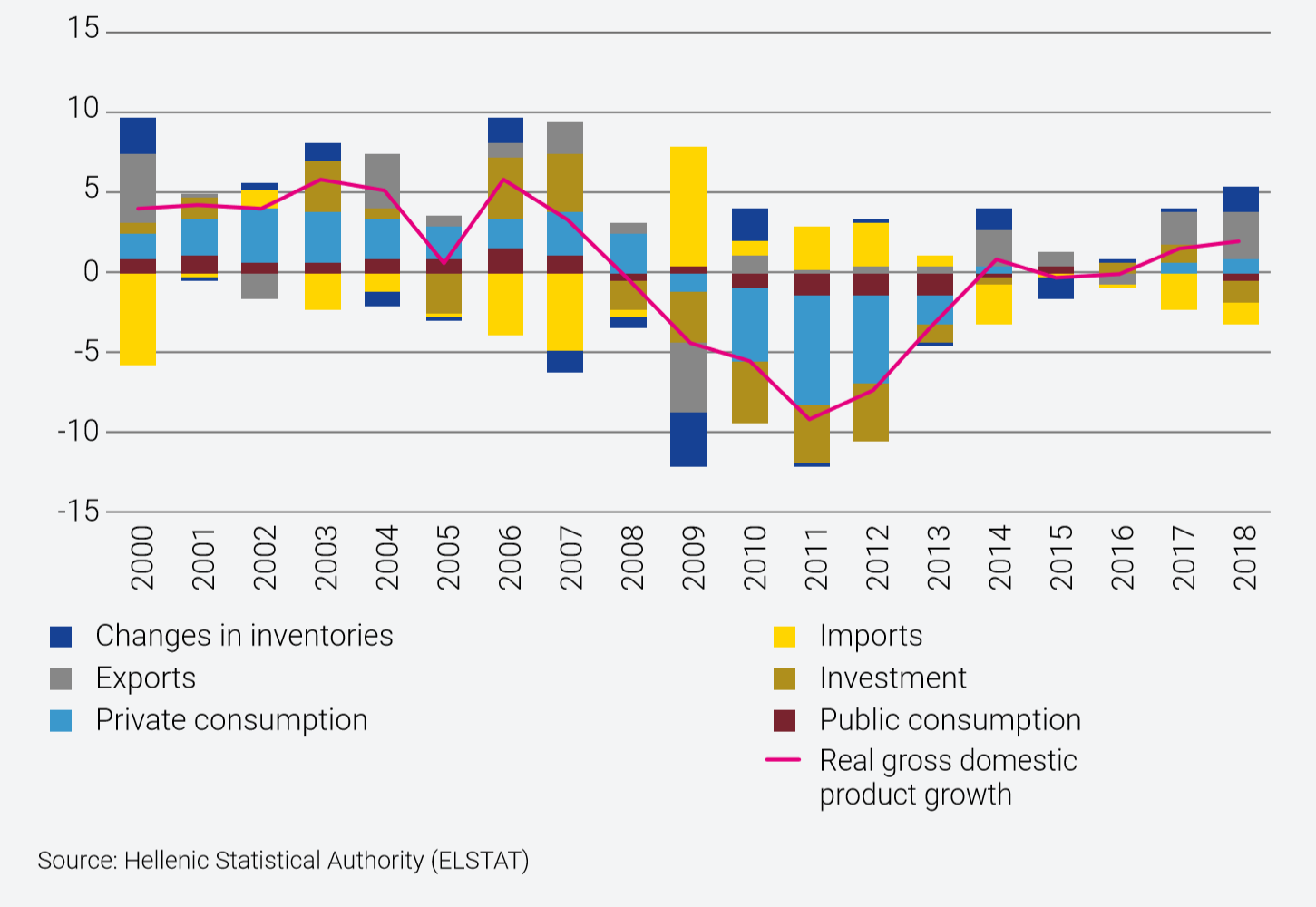

Output growth resumed with a positive outlook, thanks to productivity-boosting reforms.

Since 2008, Greece has lost almost a quarter of its GDP (Figure 18). Over recent years, however, output has stabilised and growth resumed in 2017 and 2018, with a positive outlook. Looking ahead, key reforms adopted throughout the programmes will translate into further output gains, supporting investment and exports. Reforms to improve the business environment focused on product markets and the privatisation of public assets and their improved management:

- Product market reforms: Implemented OECD competition toolkits, removed undue restrictions on regulated professions, facilitated setting up a business, removed barriers to entrepreneurship, simplified and modernised customs procedures and investment licensing procedures. As a result, between 2009 and 2019, Greece rose more than 30% on the World Bank’s ‘starting a business’ indicator, and improved its score in the Global Competitiveness Index since a collapse in 2012. But Greece still ranks quite low versus its euro area peers and should continue implementation efforts.

- Privatisations and HCAP: Privatised a variety of public assets during the programmes to improve the efficiency of the economy, by shifting resources to the private from the public sphere. Concretely, the privatisations reduce the public cost of these assets, attract foreign investment, and enhance their contribution to the Greek economy. Despite delays in implementation, the privatisation programme has advanced and will continue during the post-programme period. Beyond this, Greece established a new structure, HCAP, to manage public assets, aiming to improve the quality of public services, enhance the value of public enterprises and real estate, and create revenue streams from them. Reforms in HCAP companies should strengthen Greece’s corporate governance culture, generate funds for domestic investment, and support broader growth.

Figure 18: Real gross domestic product

(Growth in %, contributions in percentage points)

(Growth in %, contributions in percentage points)

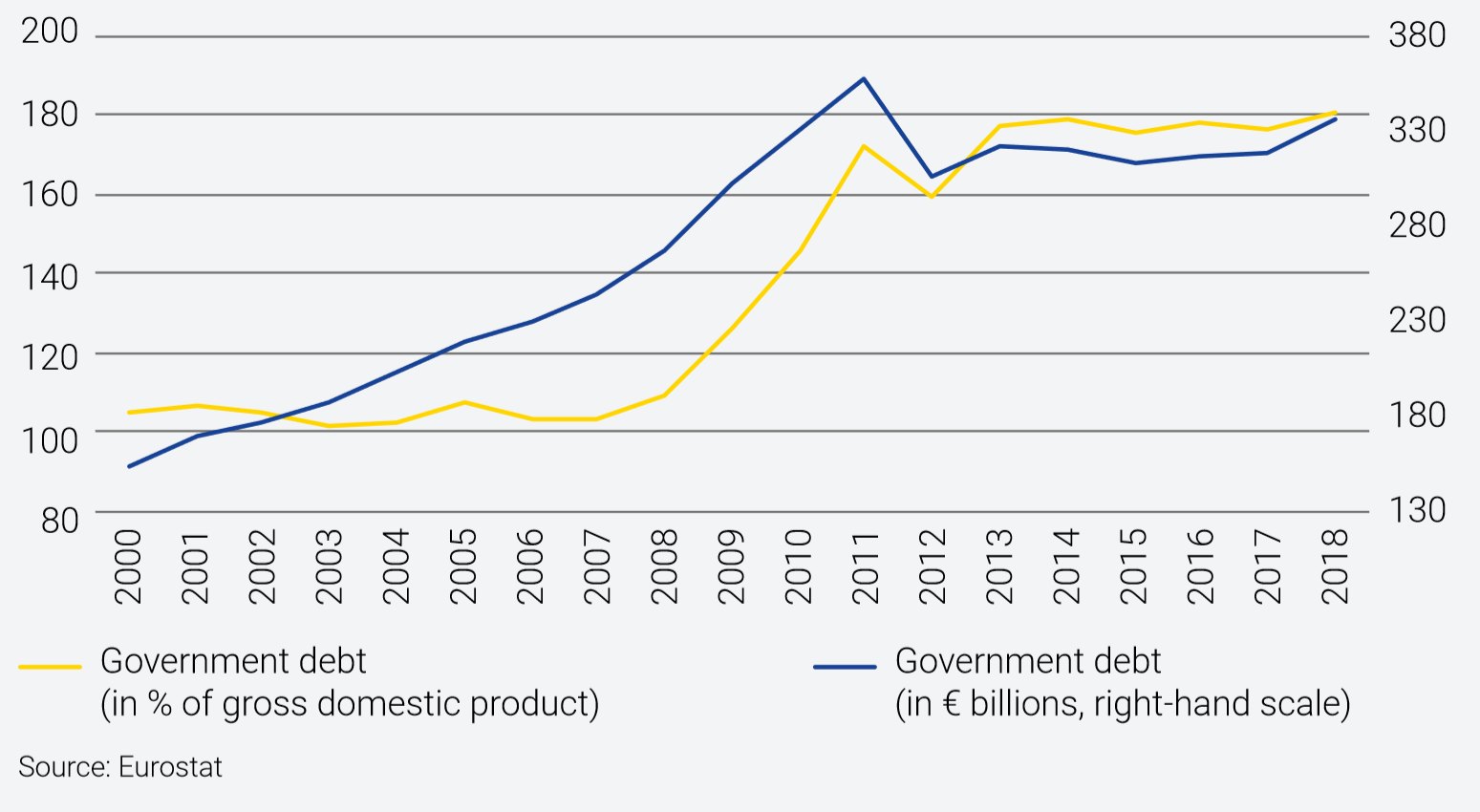

Figure 19: Government debt

Safeguarding banking sector stability was crucial to the adjustment.

The Greek banking sector has undergone waves of stress leading to structural change. Four large banks control over 95% of the market as smaller players have been merged or liquidated. The four systemic banks have received three rounds of recapitalisation, 40% of which came from private investors, in 2013 to restore capital adequacy ratios from losses arising from the write-off of Greek government bonds and again in 2014 and 2015 to cover losses from the increase in NPLs. The banks also experienced large-scale deposit outflows, which made them reliant on emergency liquidity assistance and even required capital controls to safeguard financial stability. Deposit outflows peaked in 2012 and, after a short period of recovery, peaked again in 2015. Bank deposits stabilised in 2018, enabling the government to relax capital controls gradually. As part of the 2015 recapitalisation, Greece introduced strict rules to reform bank governance. The ongoing reforms are focused on legislation to reduce the NPL ratio, which remains the highest in the euro area, and generate new bank lending to support the recovery. Banks met NPL reduction targets up to the end of 2018, and have reduced the stock of NPLs by more than €20 billion since 2016.

Risks to debt sustainability have been broadly mitigated with several sets of debt relief measures.

Greece received substantial debt relief both from private creditors in 2012 and from the official sector in 2011, 2012, 2016 and, just before the end of the third programme, in June 2018. All these debt measures have improved debt dynamics (Figure 19). Greece’s debt is expected to remain on a declining path, with gross financing needs below 15% of GDP in the medium term and below the 20% threshold in the long-term under the baseline scenario. European partners also committed to providing additional debt relief measures in 2032, if needed and provided that the EU fiscal framework is respected.

Challenges in the post-programme environment

Despite programme reforms, Greece faces key challenges to secure sustainable long-term growth.

Public finances need to remain on a sustainable path, while incorporating more growth-oriented policies. Already implemented or adopted reforms, such as the labour market reform and the lowering of income taxes in combination with a broadening of the tax base, need to be safeguarded and should not be reversed. In the event of court rulings overturning key structural reforms, the recurrent fiscal impact should be largely addressed by reforms within the same policy field. Further structural reforms are necessary to boost productivity and enhance competitiveness, complementing the country’s growth strategy. These include reforms to make the economic environment more business friendly, reduce the time needed to resolve legal disputes, further improve the effectiveness of public administration while maintaining it at its current size, and enhance the efficiency of state-owned enterprises’ management. These institutional reforms, coupled with privatisations and improved management of state assets, are critical to attracting both foreign and domestic investment and strengthening future growth. Furthermore, Greece needs to support banks’ efforts with a comprehensive NPL reduction strategy and improved legislative framework, which will help Greek banks’ ability to lend to the economy and support the economic recovery.

[1] Lennkh, R.A, Moshammer, E., and Valenta, V. (2017), A Comprehensive Scorecard for Assessing Sovereign Vulnerabilities, ESM, Working Paper 23, April 2017. https://www.esm.europa.eu/publications/comprehensive-scorecard-assessing-sovereign-vulnerabilities

Programme country experiences