The hidden web: How loss-absorbing bonds connect banks and investment funds

The size and interconnectedness of the non-bank financial sector with the rest of the financial system is a matter of increasing policy concern. [1] Investment funds’ [2] holdings of banks’ loss-absorbing bonds merit special examination given the potential for the fund industry to amplify financial shocks through concentrated exposures of these bonds in certain portfolios, which can put financial stability at risk during times of financial stress.

To improve bank crisis management following the experiences of the global financial crisis and euro area debt crisis, there was a shift of the financial burden of bank resolutions to private investors instead of on public funds. This means that debt and equity holders must bail in a failing bank, which contrasts with the past bail-out approach requiring governments to inject “innocent” taxpayers’ money.

To ensure effective bail-in, banks must have a sufficiently large amount of liabilities that can be written down or converted into equity. In the European Union, this resulted in the introduction of a loss-absorbency requirement for banks, the Minimum Requirement for Own Funds and Eligible Liabilities (MREL), which then induced banks to increase their issuances of loss-absorbing bonds, or “MREL bonds”, to comply with the new regulation [3], further intertwining the non-bank and banking sectors.

Well-established MREL bond market attracts investors, but risks are present

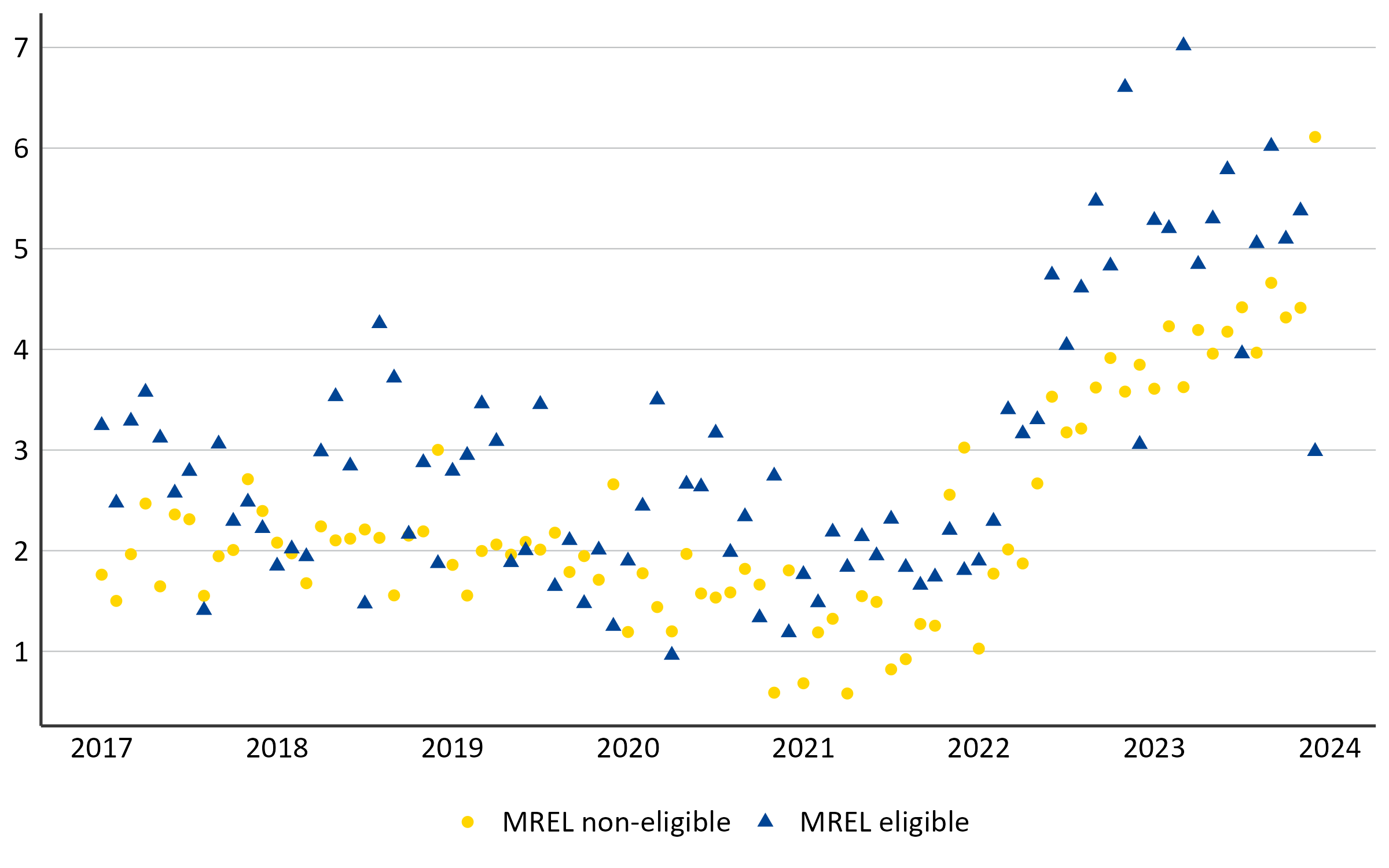

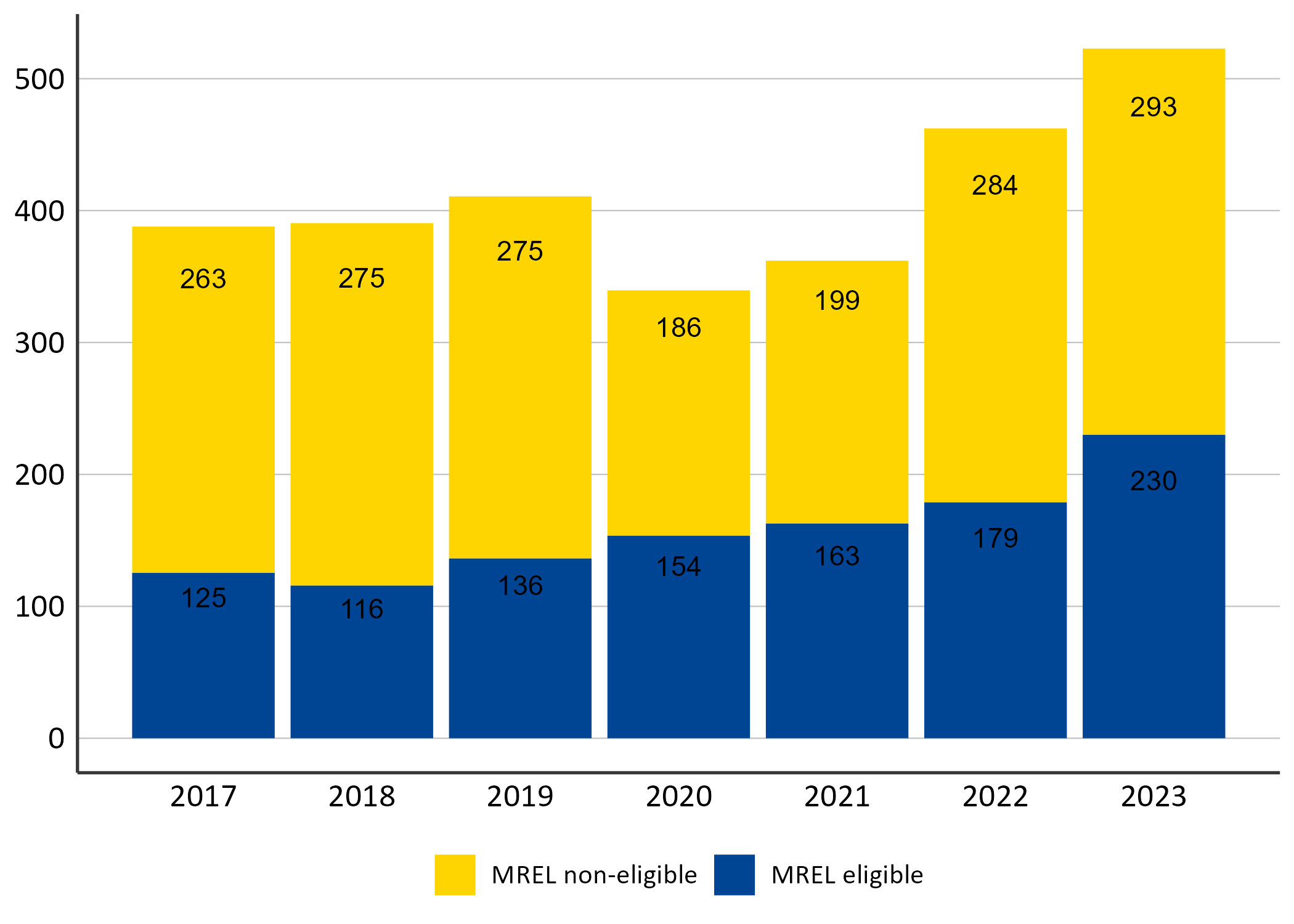

Loss-absorbing bonds are attractive to investors, especially during periods of low interest rates, given their higher returns compared to other bank debt (Figure 1). This stems from their inherently higher riskiness because they act as the first layer of defence to absorb losses when a bank runs into trouble. Between 2017 and 2023, euro area banks issued €2.88 trillion in bank debt, of which approximately €1.1 trillion was in MREL bonds. [4] Over time, the volume increased as banks had to meet binding MREL requirements by the end of 2023 (Figure 2). As of 2024, all euro area banks comply with their final requirement, thus ensuring the availability of eligible instruments to implement their envisaged resolution strategy in case of distress. [5]

Figure 1: MREL bonds offer higher yields compared to other bank debt coupons

(in %)

Note: Each dot represents the monthly average yield-to-maturity at issuance of fixed-rate bonds according to whether they are MREL eligible.

Source: ESM calculations based on Dealogic and Bloomberg

Figure 2: Banks’ MREL bond issuance has steadily increased over time

(in € billion)

Note: To identify MREL bonds (other than Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital), we focus on those instruments for which the MREL-eligibility is clearly identified by the “non-preferred” status. As a result, the analyses might be underestimating the overall size of the MREL market.

Source: ESM calculations based on Dealogic and Bloomberg

While the market is currently well-established and operational, the inherent risk and volatility of these instruments mean that a single incident can significantly impact market functioning. The Credit Suisse episode of March 2023 is a stark reminder of this. CHF 16.5 billion of Additional Tier 1 instruments were written off to stabilise the bank and ensure a smooth merger with UBS. [6] This event resulted in a market freeze of Additional Tier 1 bonds for a few months before investors’ appetite could be restored.

Funds’ appetite for euro area banks’ MREL bonds brings financial stability benefits

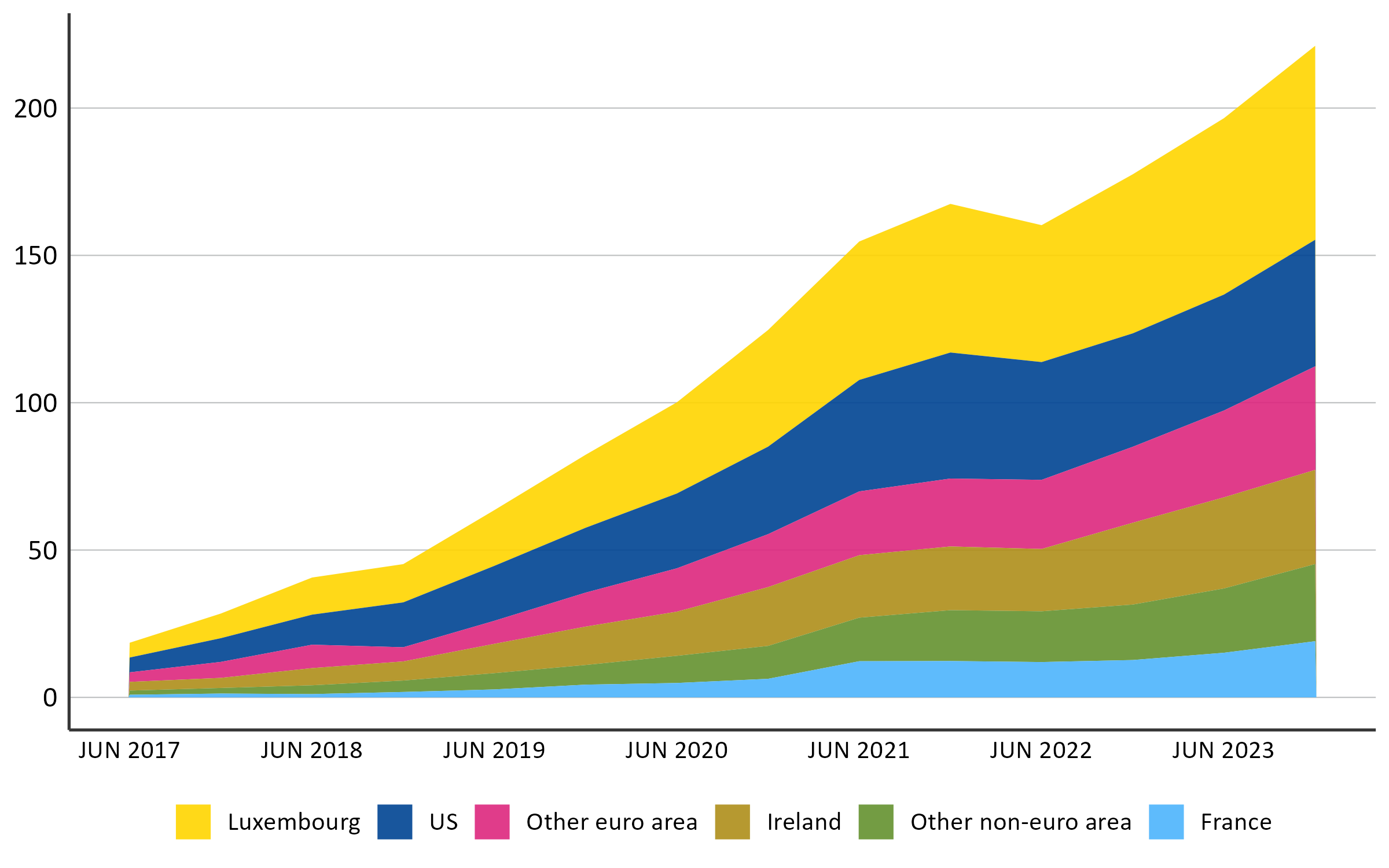

Investment funds are key players in the market for MREL bonds, next to insurance companies and banks, and their appetite for them has expanded in step with banks' heightened issuance of such bonds. As of the end of 2023, the global investment fund industry held approximately €221 billion in MREL bonds issued by euro area banks since 2017. The United States (US) and the euro area (especially in its main fund industry hotspots of Luxembourg and Ireland) are the jurisdictions most exposed, with the US accounting for 12% and the euro area for 69% of investment funds’ total exposure, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Funds’ holdings of MREL bonds have increased across jurisdictions

(in € billion, market value)

Note: Funds’ holdings of MREL bonds consider only MREL instruments issued from 2017, and, as such, we might be underestimating the overall size of this market.

Source: ESM calculations based on Lipper and Dealogic

There are benefits to financial stability stemming from investment funds being active buyers of MREL debt:

- Increased market liquidity and lower funding costs. By investing in MREL bonds, investment funds increase this market’s demand and thus its liquidity. The higher liquidity leads to lower yields and more favourable pricing for MREL bonds, ultimately reducing banks' overall cost of funding.

- Diversification and strengthened resilience of the financial system. The participation of investment funds in the MREL market diversifies its investor base, reducing the risk of concentration among other sectors of the economy such as other financial institutions and households. Furthermore, because investment funds pool money from many different investors, risks are spread among many actors, strengthening the overall resilience of the financial system.

The fragile web: funds’ concentration in MREL bonds can increase the risk of abrupt market corrections

Despite the positive aspects of investment funds buying MREL bonds, the resulting interconnection can become a source of risk and vulnerability during times of financial stress. There are several scenarios with the potential for contagion and creating a vicious cycle of banks-investment funds distress. For example, should a bank run into trouble:

- Investment funds that have invested in MREL instruments of the bank in distress could try to anticipate the bail-in event and fire sell their MREL investments in an effort to avoid losses. Due to herd behaviour, this action could trigger other investment funds to follow suit and sell off their MREL investments in the bank too.

- Investment funds might strategically decide to sell their holdings of other MREL instruments due to fears that the crisis could spread to other banks, causing losses on their MREL investments. By doing so, they would actually realise the contagion, spreading the distress initially isolated in one bank to the broader banking system.

- Investment funds heavily exposed to MREL instruments would, in the event of a bank failure, become susceptible to exceptional investor redemption demands. To manage those liquidity needs [7], investment funds may be forced to rapidly restructure their portfolios. As MREL bonds’ liquidity would likely deteriorate in such a scenario, they might need to fire sell other assets in their portfolio, which creates an additional contagion channel affecting previously unaffected market segments, thereby amplifying the original shock throughout the financial system.

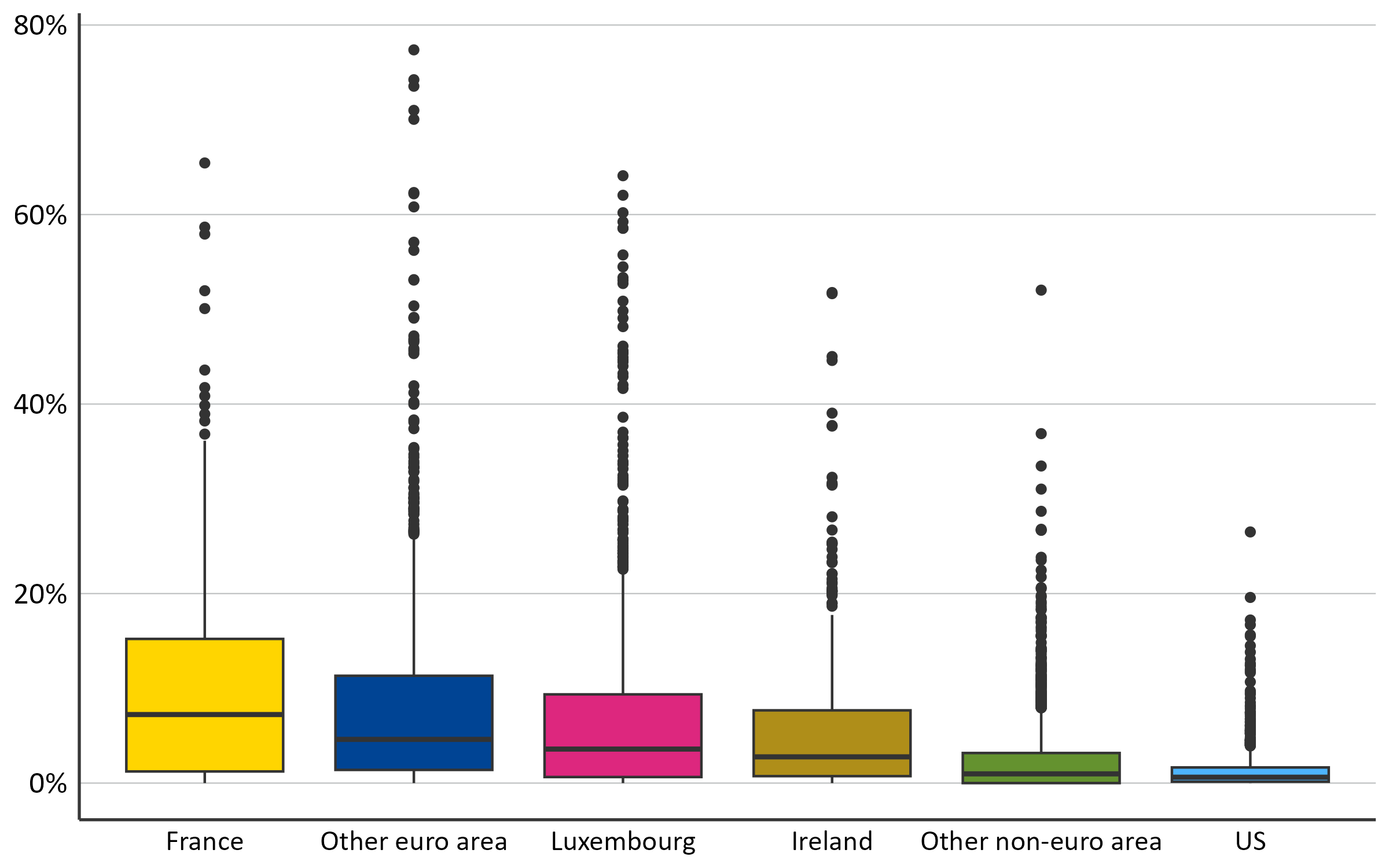

The possibility of contagion effects calls for a thorough understanding of the presence of concentrated exposures of MREL bonds at the level of individual funds. [8] In Figure 4, we observe euro area funds exhibiting a high share of their portfolio in loss-absorbing securities, rendering them particularly vulnerable to euro area banking sector distress. By contrast, MREL bonds represent only a small fraction of the portfolios of non-euro area funds, with also fewer investment funds showing high concentration (as represented by the black dots).

Figure 4: MREL bonds account for a meaningful share of euro area funds’ portfolios

(in % of assets under management, Q4 2023)

Notes: This figure illustrates the distribution of the weights of MREL securities in the portfolio of open-ended funds by domicile. The upper and lower horizontal lines of each boxplot correspond to the first and third quartiles of portfolio weights, while the horizontal line in the middle corresponds to the median. The dots represent outlier funds with a total MREL weight significantly higher than most others (greater than the third quartile by a factor proportional to the height of the box).

Source: ESM calculations based on Lipper and Dealogic

A high level of concentrated exposure can create a clustering effect, whereby similar investment strategies among these funds lead to coordinated selling during periods of financial stress. This synchronised behaviour might overwhelm the market's capacity to absorb the bonds being sold, resulting in price dislocations.

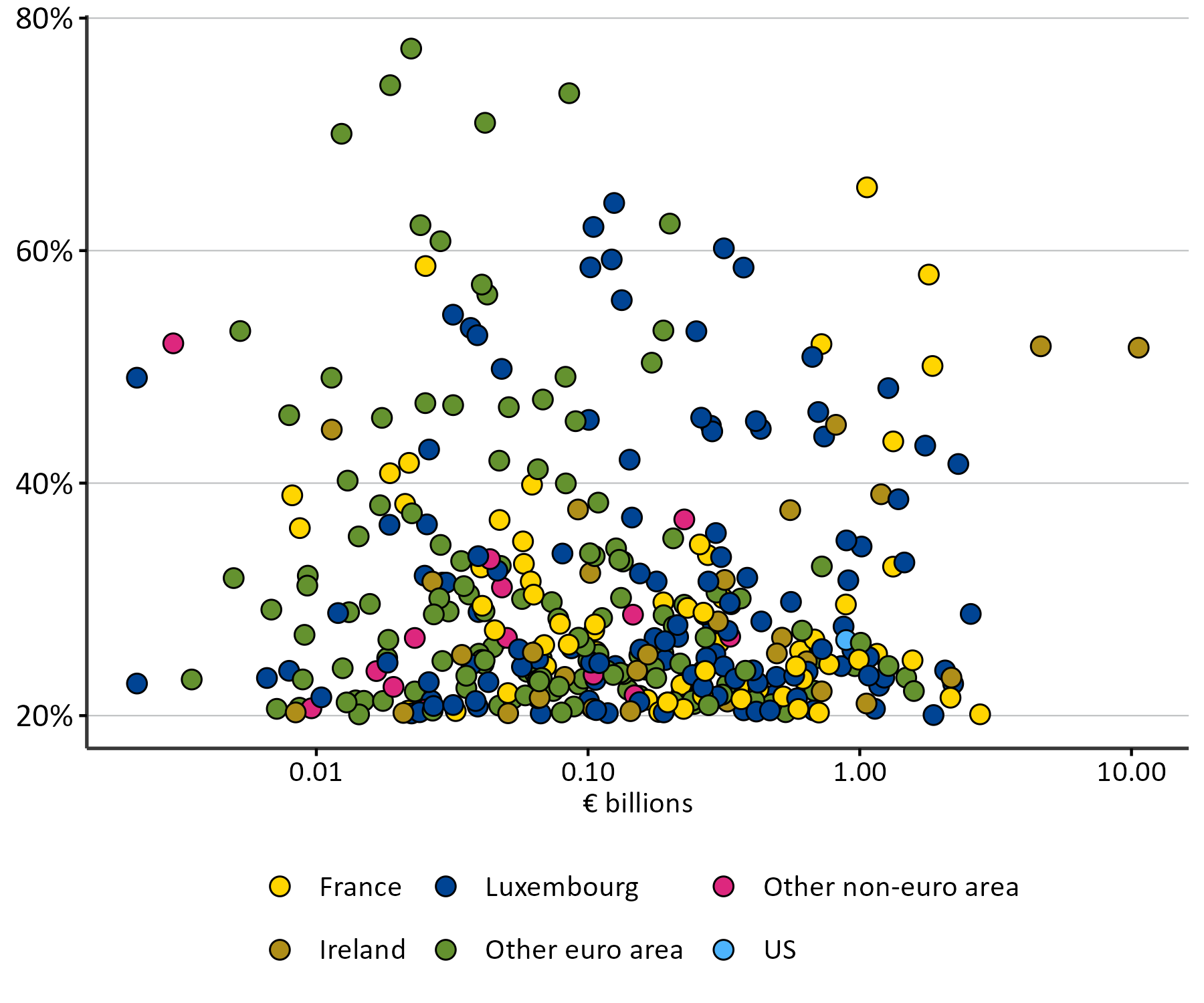

This issue of concentrated exposures is heightened by the presence of very large players among these funds. Zooming into those investment funds with more than 20% of their portfolios invested in MREL instruments, we find significant funds with assets under management above €1 billion domiciled in the euro area (Figure 5).[9]

Figure 5: MREL investment intensity: a size perspective

(% of funds with more than 20% concentration, Q4 2023)

Notes: Funds with concentrated exposure to MREL are defined as those with more than 20% of the portfolio invested in MREL bonds. The x-axis represents the fund size through the total value of assets held in € billions, while the y-axis depicts the percent proportion of a fund’s portfolio invested in MREL bonds. To make the scale of the variables comparable we use log-10 scale on the funds’ size but convert the axis labels to the original scale.

Source: ESM calculations based on Lipper and Dealogic

Security and stability for today, and tomorrow

There is now a large, well-established and functioning market for euro area banks’ MREL bonds. Investment funds have significantly grown their positions in these instruments over the last few years, resulting in a deeper and stronger tie between banks and non-banks.

The fund industry appears well placed to hold these assets thanks to their diversified portfolios, relatively long-term investment horizons, and risk profiles. However, the concentration of MREL holdings raises financial stability concerns given these instruments exposure as they are the first to absorb losses when a bank runs into trouble. For this reason, enhanced monitoring of these trends is warranted.

To address some of these concerns, funds with concentrated positions in MREL bonds are expected to follow enhanced risk management processes that consider the specificities of these bonds, especially the likelihood of the trigger event. Regular stress testing exercises accounting for the correlation between market stress and potential trigger events could serve as an effective mitigation measure.

Furthermore, the availability of liquidity management tools is particularly relevant for MREL concentrated funds, because these tools can be instrumental in preventing fire sales. While recent progress has been made in this direction [10], further implementation of the Financial Stability Board’s recommendations for addressing investment funds’ structural vulnerabilities [11] could help in mitigating the risks of MREL holdings by these funds.

For bank resolutions, it remains essential to have accurate information on the nature of the holders of these MREL instruments, as already highlighted by many authorities. [12] It is important to assess who would bear the losses from the failure of a bank, and what would be the impact on the broader financial system. In Europe, supervisors have access to the proprietary Securities Holdings Statistics by Sector data, but it only allows for the identification of MREL holders domiciled in the euro area. Given the global footprint of the players in the MREL bonds market, reinforcing cross-border cooperation and coordination among authorities is needed to enhance disclosures of MREL bonds and, ultimately, protect the health of the financial sector and maintain financial stability.

Further reading

Attinà, C.A. and Bologna, P., (2021). TLAC-eligible debt: who holds it? A view from the euro area. Bank of Italy Occasional Paper (604).

Bank for International Settlements (2021). Liquidity management and asset sales by bond funds in the face of investor redemptions in March 2020. BIS Bulletin No.3, March 2021.

European Banking Authority (2024). Risk assessment report of the European Banking Authority, November 2024

European Central Bank (2021). Investment funds’ procyclical selling and cash hoarding: a case for strengthening regulation from a macroprudential perspective. Financial Stability Review, May 2021

European Central Bank (2022). Liquidity mismatch in open-ended funds: trends, gaps and policy implications. Financial Stability Review, November 2022

Farina, T. et al. (2022): Is there a "retail challenge" to banks' resolvability? What do we know about the holders of bail-inable securities in the Banking Union?, SAFE White Paper, No. 92

Financial Stability Board (2021). Evaluation of the Effects of Too-Big-To-Fail Reforms. Final Repost, April 2021

Financial Stability Board (2023). Revised Policy Recommendations to Address Structural Vulnerabilities from Liquidity Mismatch in Open-Ended Funds. Financial Stability Board, 2023.

Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (2023). Lessons Learned from the CS Crisis. 20231219-finma-bericht-cs.pdf

Joint Committee of the European Supervisory Authorities (2024). Joint committee report on risks and vulnerabilities in the EU financial system. August 2024, JC 2024 65.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Paolo Fioretti, Nicoletta Mascher and Rolf Strauch for the valuable discussions and contributions to this blog post, Raquel Calero for the editorial review.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager