Through the looking glass: granular evidence to strengthen economic resilience to physical climate risk

Europe is already feeling the effects of a rapidly warming climate. Higher temperatures and severe floods, storms and wildfires have become defining features of recent years (see Figure 1). But what this means for macroeconomic stability and policy is not fully understood. To shed more light on how extreme weather events affect the economy, we focus on the case of Spain and combine economic data at the most detailed regional level and at the highest temporal frequency available with high-resolution meteorological information for Spain’s continental provinces since 2000.[1] Through the looking glass of high-resolution data, we are able to assess what happens to economic activity after a flood, windstorm or wildfire hit, precisely where and when these shocks’ effects are most acutely felt.

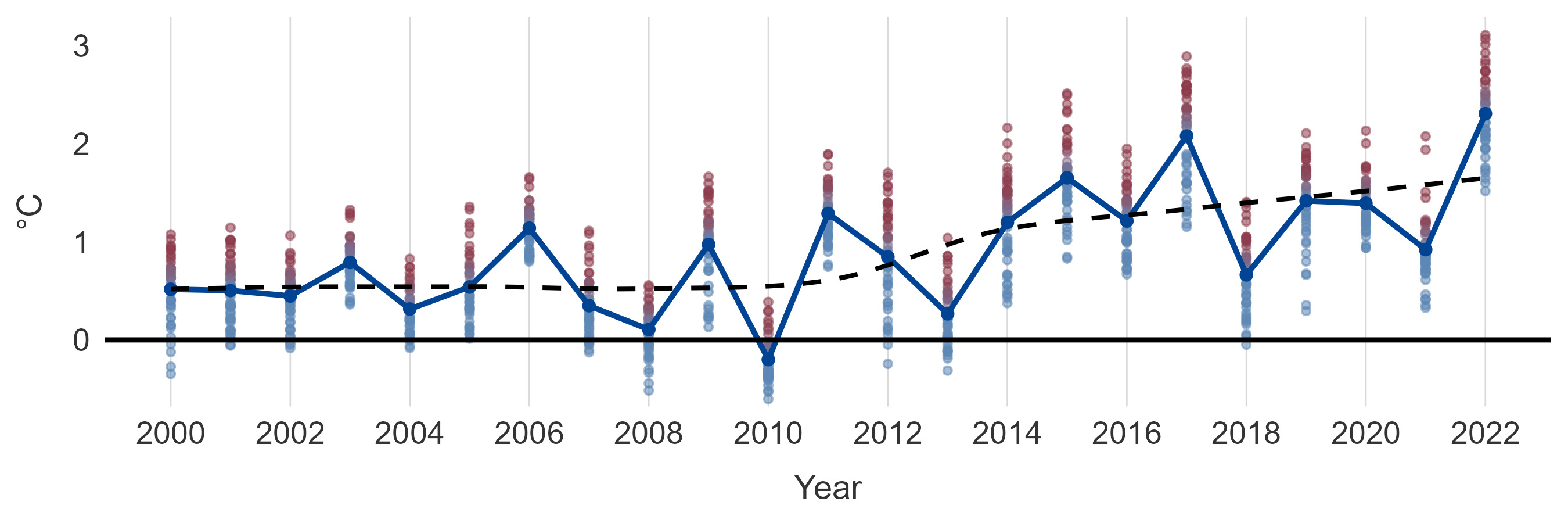

Figure 1

Average maximum temperature anomaly

(Continental Spain, 2000-2022)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on AgERA5. Anomaly in maximum average annual temperature across regions compared to the 1979-1999 mean of maximum average annual temperatures.

The macroeconomic impacts of floods, windstorms and wildfires are significant

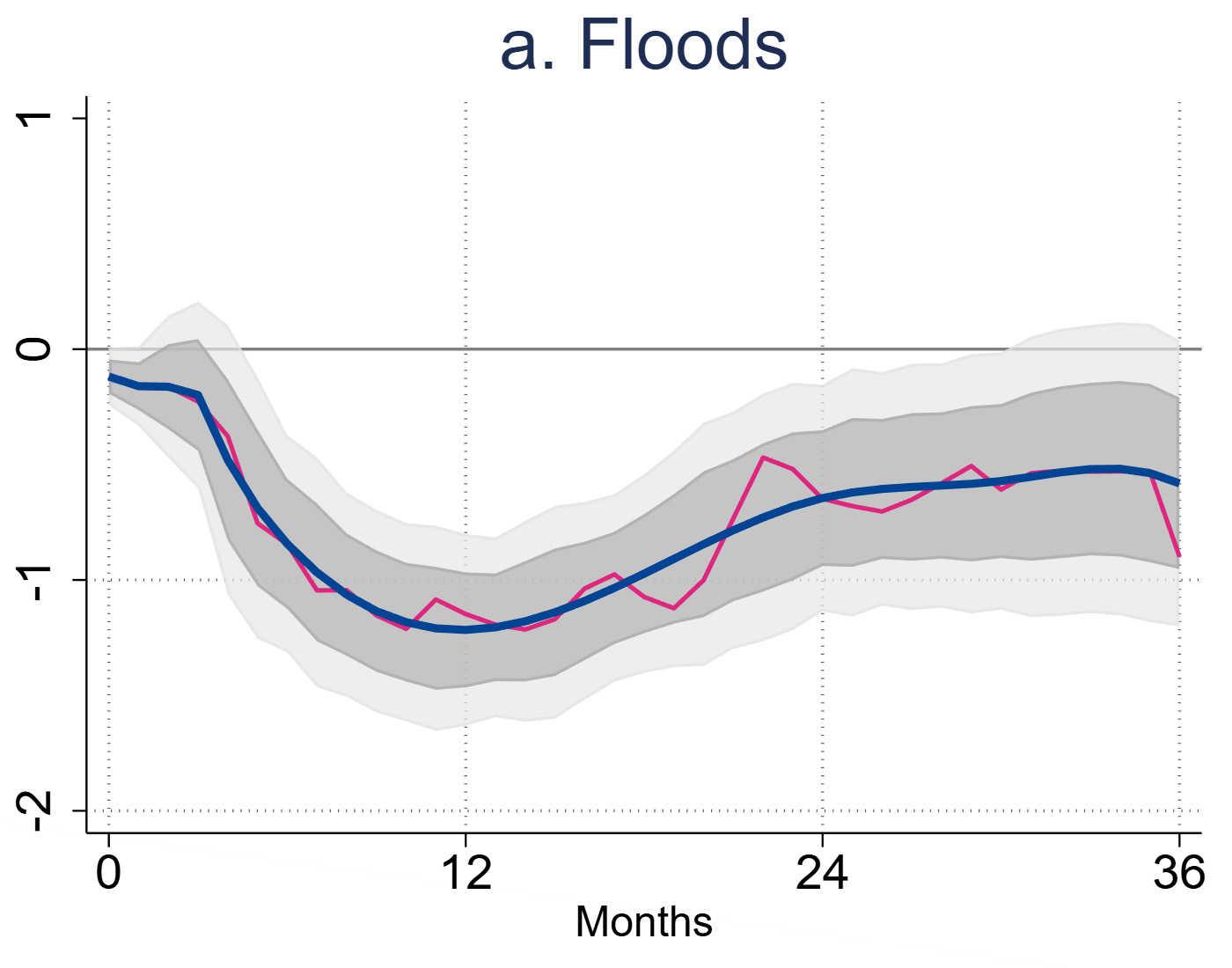

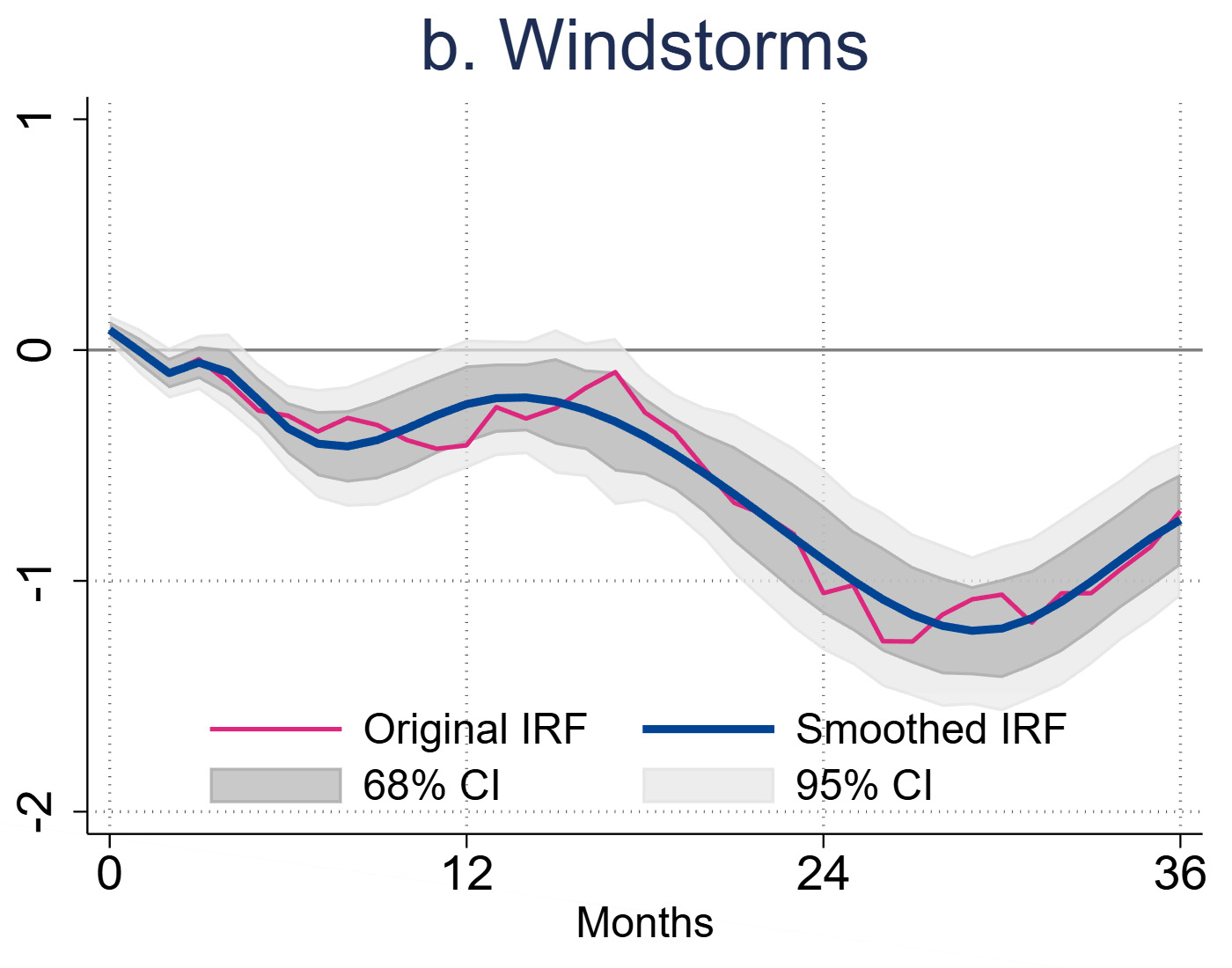

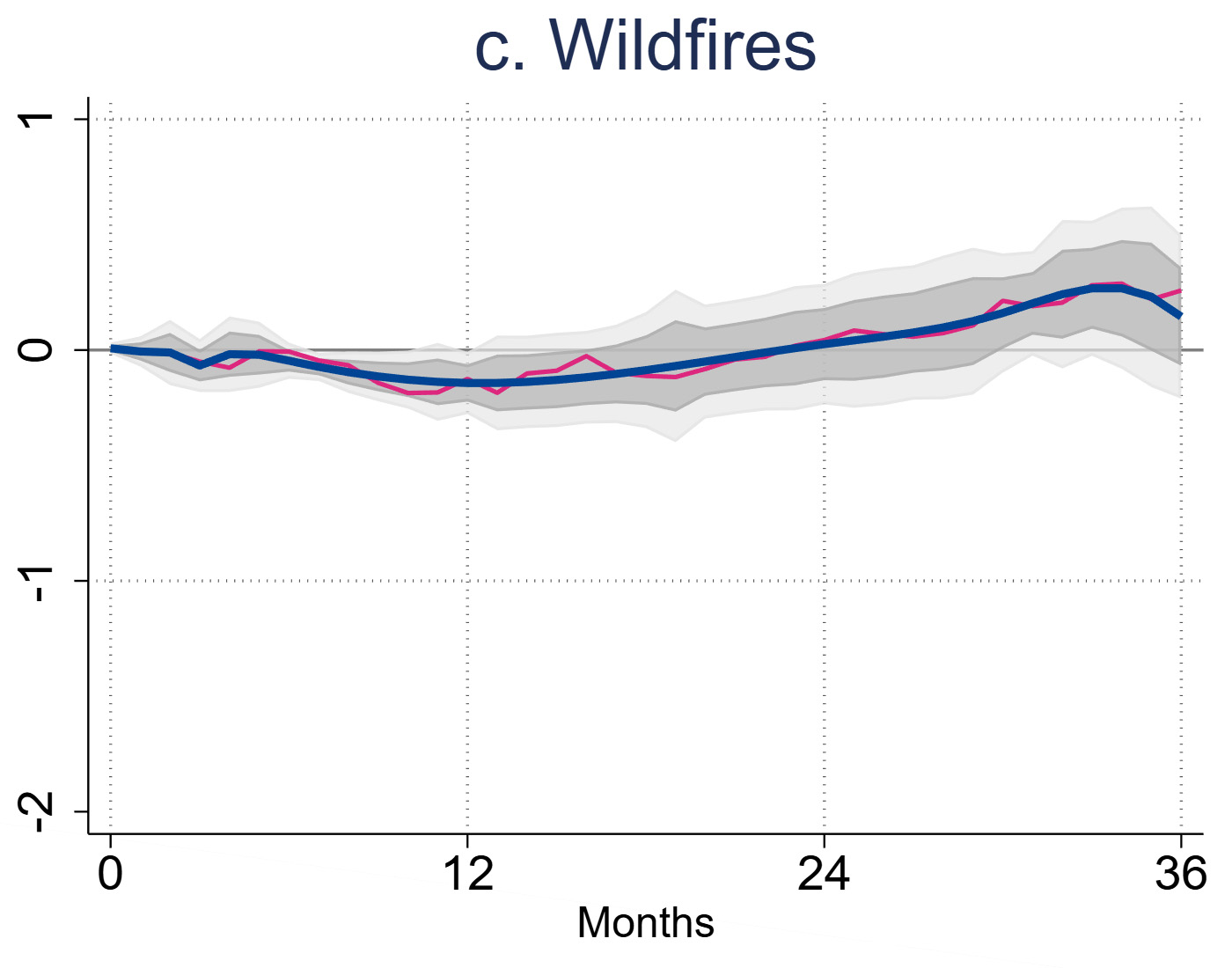

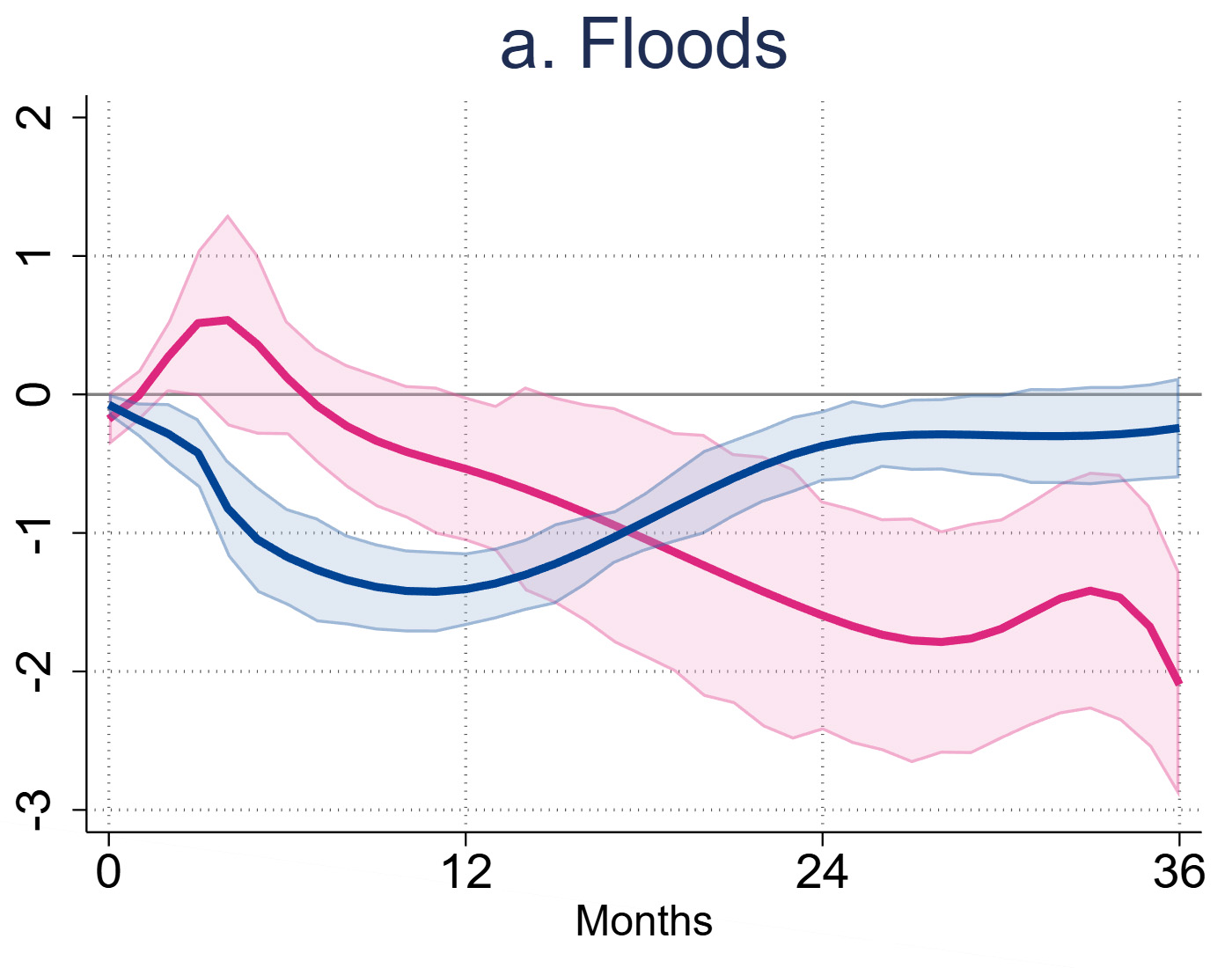

Our analysis reveals a clear pattern: extreme weather shocks reduce economic activity, and effects persist for years (see Figure 2). Floods and windstorms cause the largest economic losses. Both reduce regional output per capita by around 1 percentage point at their peak. Floods hit activity quickly, with the largest decline seen within 12 months. Windstorms’ effects build more slowly but remain damaging for longer: output is still about 0.8 percentage points below its pre-event level three years after a storm. Wildfires, by contrast, cause only a short-lived decline of around 0.2 percentage points, with activity returning to normal within two years. This reflects the fact that agricultural and generally less populated areas of Spain tend to be most affected by wildfires, as opposed to densely built environments.

Figure 2

Impulse responses of per capita GDP to extreme weather events

(Percentage points deviation from pre-shock level, panel local projections)

Note: graphs show impulse responses functions, derived from a panel local projections approach, in response to an average shock of the type mentioned above the chart.

Why do extreme weather events matter so much for economic activity? Floods, windstorms and wildfires each affect the economy differently, but share some important features: they destroy physical capital and weigh on employment. We find that for all three shock types, employment falls after an event – though by less than output – and recovers only gradually.

Interestingly, we do not see a boom in investment after extreme weather events. New construction, a proxy for investment, remains somewhat subdued after floods and declines sharply after windstorms, suggesting that resources are bound up in reconstruction and that households postpone investment because incomes are lower. Meanwhile, tourism is an important transmission channel, particularly for floods. Nights spent in tourist accommodation drop sharply after floods and recover only slowly. Damaged infrastructure or transport disruptions contribute to this prolonged weakness.

Better insurance coverage means faster recovery

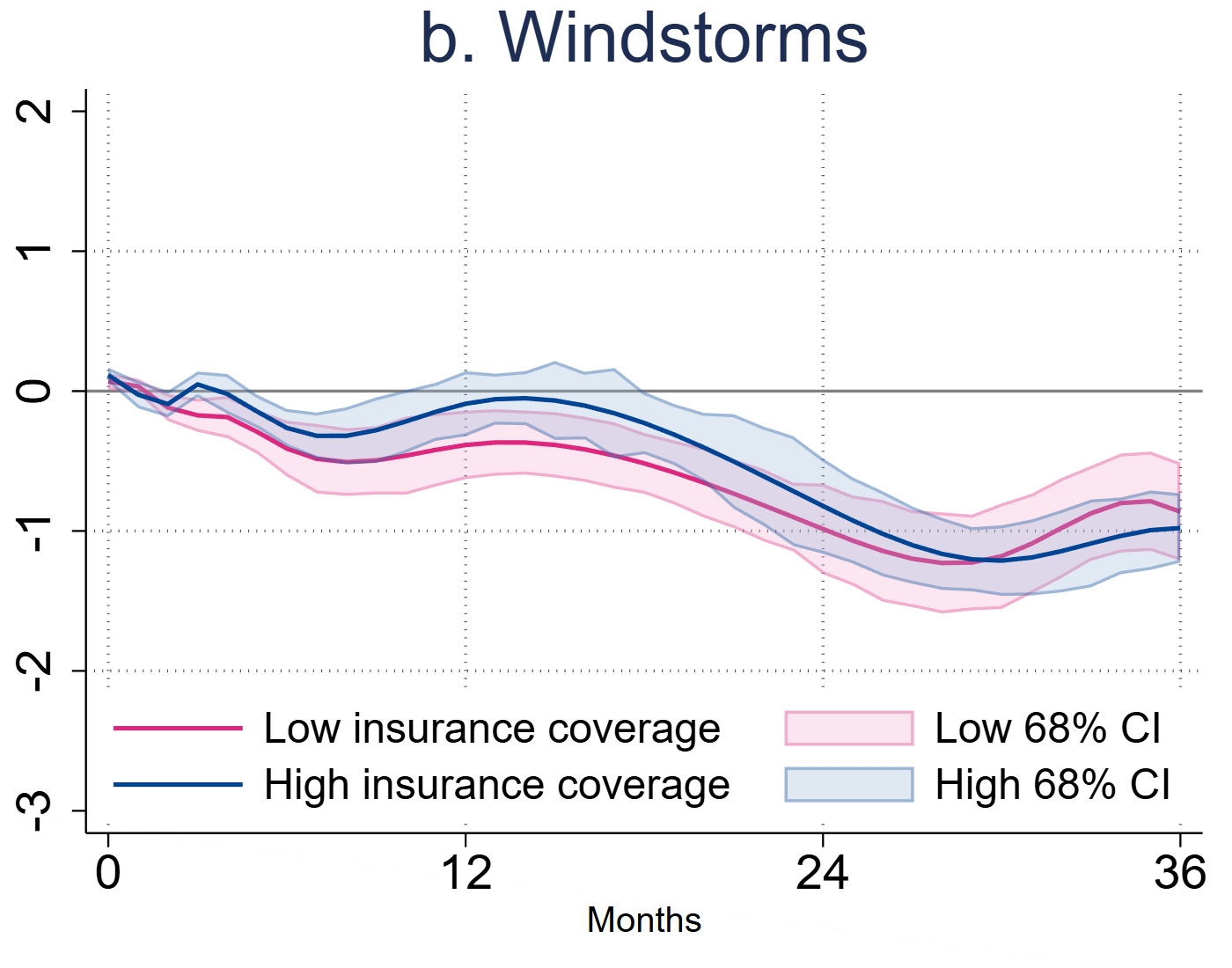

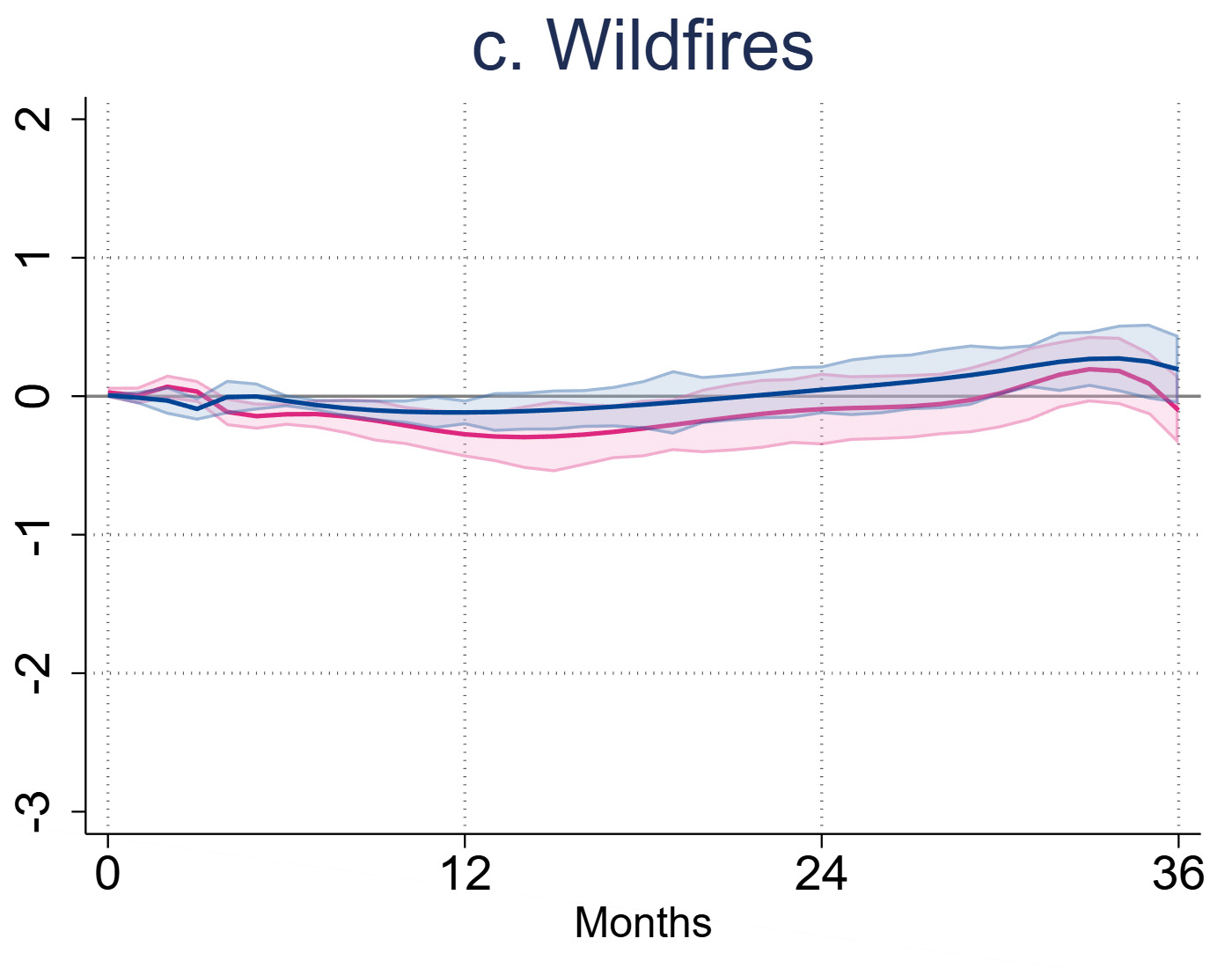

Insurance coverage plays an important role in shaping how regions recover from extreme weather events. This is above and beyond other factors not discussed here that include capital density, for example. Our results suggest that in regions with higher insurance coverage, recovery is faster and permanent damage is more limited, especially in case of floods (see Figure 3).[2] In regions with lower insurance coverage, losses remain significant even three years after a flood, at about 2 percentage points of GDP. This compares to no significant impact for regions with high insurance coverage.[3]

The results also relate to a broader issue: Spain, and Europe more broadly, face an insurance gap. A significant share of physical capital is un- or underinsured, and coverage varies widely across countries and regions. In the case of Spain, this happens despite its public insurer of last resort covering some extreme weather-related damages. The national-level backstop is sufficiently large to absorb losses from individual events. However, the scheme only applies when a private insurance policy has been purchased and only covers damages from events deemed extraordinary. The insurance gap matters because uninsured losses slow down repairs, require larger fiscal interventions and ultimately cause a greater macroeconomic impact (Von Peter et al., 2024). Thus, taking steps towards reducing the insurance gap could reduce macroeconomic volatility in the face of extreme weather events.

Figure 3

Impulse responses of output to extreme weather events, by degree of insurance coverage

(Percentage points deviation from pre-shock level, panel local projections)

Note: graphs show impulse responses, derived from a panel local projections approach, in response to an average shock of the type mentioned above the chart.

Lessons for macroeconomic policy amid accelerating climate change

Extreme weather events look set to become more frequent and more severe as climate change accelerates (IPCC, 2021). Our analysis for Spain shows that these shocks, especially floods and windstorms, have significant and persistent macroeconomic effects on output and employment. Three implications for macroeconomic stabilisation policy emerge.

First, recovery mechanisms need to account for the long duration of economic losses. Support may be needed well beyond the immediate aftermath of an extreme weather event.

Second, increasing insurance coverage will support economic resilience as physical climate risks intensify. Regions with higher insurance coverage recover faster and suffer smaller long-term losses, protecting fiscal space. A European backstop for natural catastrophes offers further diversification benefits in absorbing tail risks beyond (re-)insurer capacity, as highlighted in a recent ESM Discussion Paper (Hahn and Mayr, 2024).

Third, adaptation and improving resilience will be key to reducing the macroeconomic and fiscal costs of extreme weather events. Adaptation remains significantly more cost-effective than ex-post reconstruction. This will matter especially for flood-prone regions, and those where economic activity or capital are concentrated. Insurance should not be considered a substitute for adaptation, but a complement to it.

Overall, the size and persistence of extreme weather events’ effects make them genuine macroeconomic shocks. There are therefore important steps that should be taken to limit their impact, and to increase resilience in the face of rising climate risks.

References

Ali, E., Cramer, W., Carnicer, J., Georgopoulou, E., Hilmi, N.J.M., Le Cozannet, G., & Lionello, P. (2022). Cross-Chapter Paper 4: Mediterranean Region. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 2233–2272). Cambridge University Press.

Copernicus Climate Change Service (2020): Agrometeorological indicators from 1979 to present derived from reanalysis. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS).

Copernicus Climate Change Service (2025): Windstorm tracks and footprints derived from reanalysis over Europe between 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS).

Felbermayr, G. & Gröschl, J. (2014). Naturally negative: The growth effects of natural disasters. Journal of Development Economics, 111, 92–106.

Hahn, M. and B. Mayr (2024): Broadening the scope of risk sharing through a European backstop for natural catastrophes. ESM Discussion Paper Series, No 24, November 2024.

Von Peter, G., Von Dahlen, S. & Saxena, S. (2024). Unmitigated disasters? Risk sharing and macroeconomic recovery in a large international panel. Journal of International Economics, 149, 103920.

M. Gavilan-Rubio and J. Peppel-Srebrny (2025): The macroeconomic effects of extreme weather events in Spain: a high-frequency, regional approach, ESM Working Papers, no. 74, December 2025.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Giovanni Callegari, Pilar Castrillo, Martina Perez, and Peter Lindmark for their valuable suggestions and contributions to this blog.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager