Euronomics: Shifting geoeconomic landscape calls for action

Financial markets are currently calm and rather optimistic. Expectations of a smooth path of monetary policy easing by major central banks, fairly robust growth in the next two years, and avoidance of worst-case scenarios are nurturing high asset price valuation. Yet, medium- to long-term problems persist in Europe that require action. The trade deal between the United States (US) and the European Union (EU) poses challenges to Europe’s competitiveness, and an agreement on defence spending among NATO Members will require budgetary prioritisation to fortify fiscal sustainability.

Trade – a brave new world

The recent overhaul of US trade policy has rapidly transformed the global trade order. As the largest trade bloc worldwide, Europe is directly affected. The US move towards a more mercantilist and transactional approach, away from multilateral rules, means continuous risks of price and competitiveness changes. The ongoing war of Russia against Ukraine and conflicts in the Middle East still shape Europe’s economic and financial relationships, notably through sanction regimes, and are potential sources of disruption.

After months of tensions, an EU-US trade agreement that carries several immediate benefits was struck this summer. It reduced uncertainty, avoided a trade war, and averted the US administration imposing its maximum tariff threat. In fact, the deal reached in August injects a measure of predictability into cross-Atlantic trade and limits negative outcomes. Most observers envisage limited impact of tariffs on growth and inflation in the euro area. Yet, a number of structural impediments remain that rein in an unambiguously optimistic conclusion on the economic impact:

- The deal has only been announced as a political statement that has already been challenged by the US administration. Implementation and enforcement are yet to be settled, and tensions could easily resurface.

- The deal dilutes European competitiveness in key manufacturing industries that typically drive productivity growth. Competitiveness is further undermined by trade diversion, notably from China. Chinese exports are competing with European products in an increasing number of sectors, and China is aiming to forge closer trade alliances with other major emerging markets.

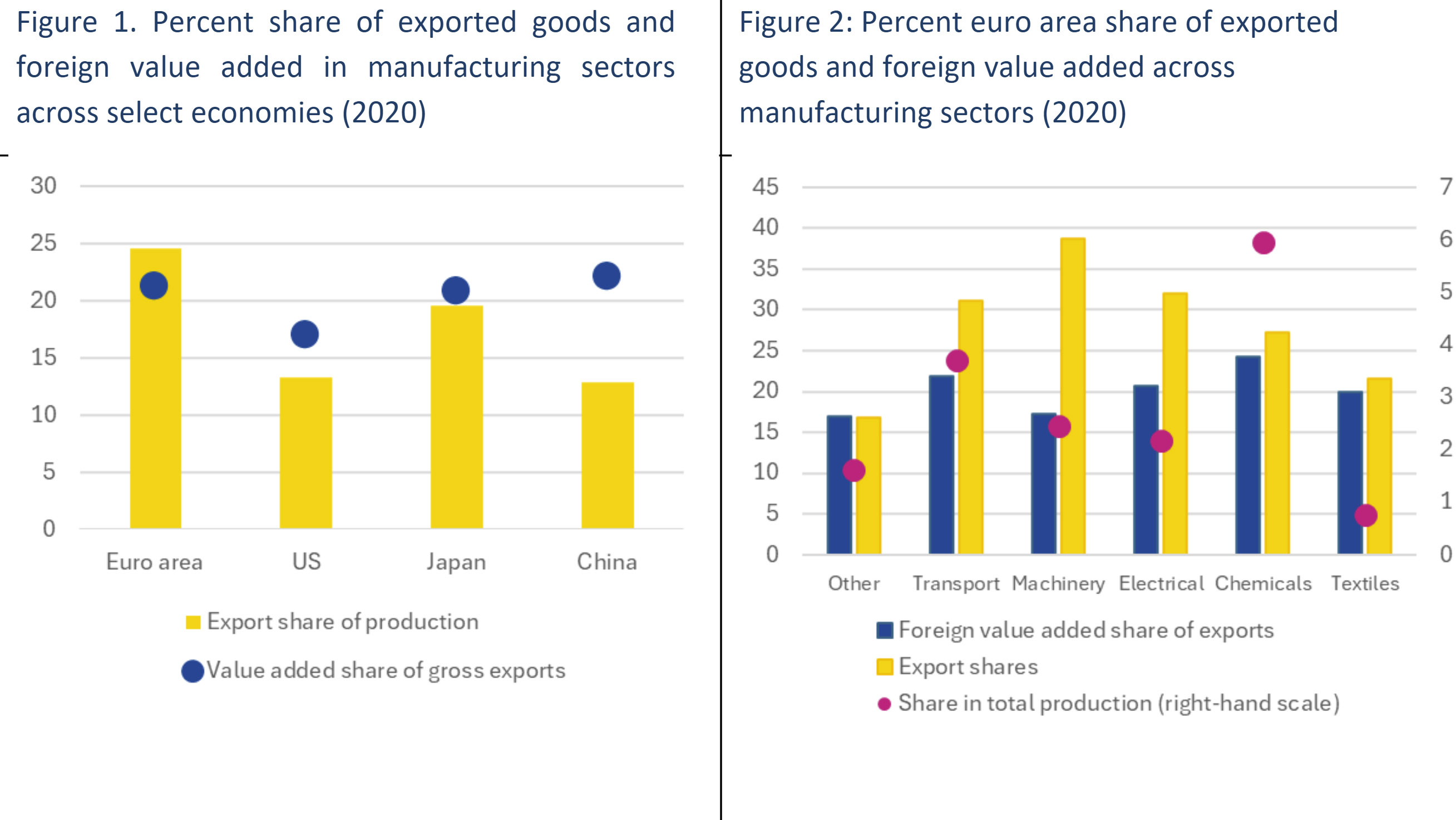

- The EU’s limited control over key trade chokepoints and relatively high dependence on external demand (see Figures 1 and 2) risk making it a passive actor subject to the decisions of other trading blocs. This is compounded by the EU’s reliance on imports for vital resources and components (especially in manufacturing goods) along with a lack of technological innovation, perpetuating dependence on vital US services.

Defence and growth – the impact on fiscal buffers and adjustment

The Russian invasion of Ukraine was a watershed moment in European security, upending decades of post-Cold War assumptions. Simultaneously, the US’s partial disengagement from traditional European security commitments has intensified the EU’s need for strategic autonomy and its own security architecture. European leaders have committed to ramp up defence spending to 3.5% of GDP among European NATO members reflecting these new priorities.

Massively enlarging defence spending will transform Europe, shifting the focus beyond weaponry to the ability to design, produce, and sustain advanced technologies at scale. In the US, defence spending exhibits a higher fiscal multiplier (ranging from 0.6 to 1.5), thanks to a robust domestic defence industry, strong links with civilian innovation, and less reliance on imports. By contrast, Europe’s defence spending multipliers are lower due to greater economic openness, higher dependence on imports, and personnel costs.

To meet the higher spending needs, it has been decided to create some room within the existing common fiscal framework and supportive EU financing, with the so-called Security Action for Europe (SAFE) instrument which provides favourable financing for defence projects under certain conditions. Enabling countries to activate national escape clauses under the common fiscal framework will allow ramping up defence spending without triggering excessive deficit procedures. To date, 15 countries have applied to activate national escape clauses and, so far, 19 countries have requested funding through the SAFE programme, exhausting its €150 billion envelope.

Trade and security – facing future adjustment needs

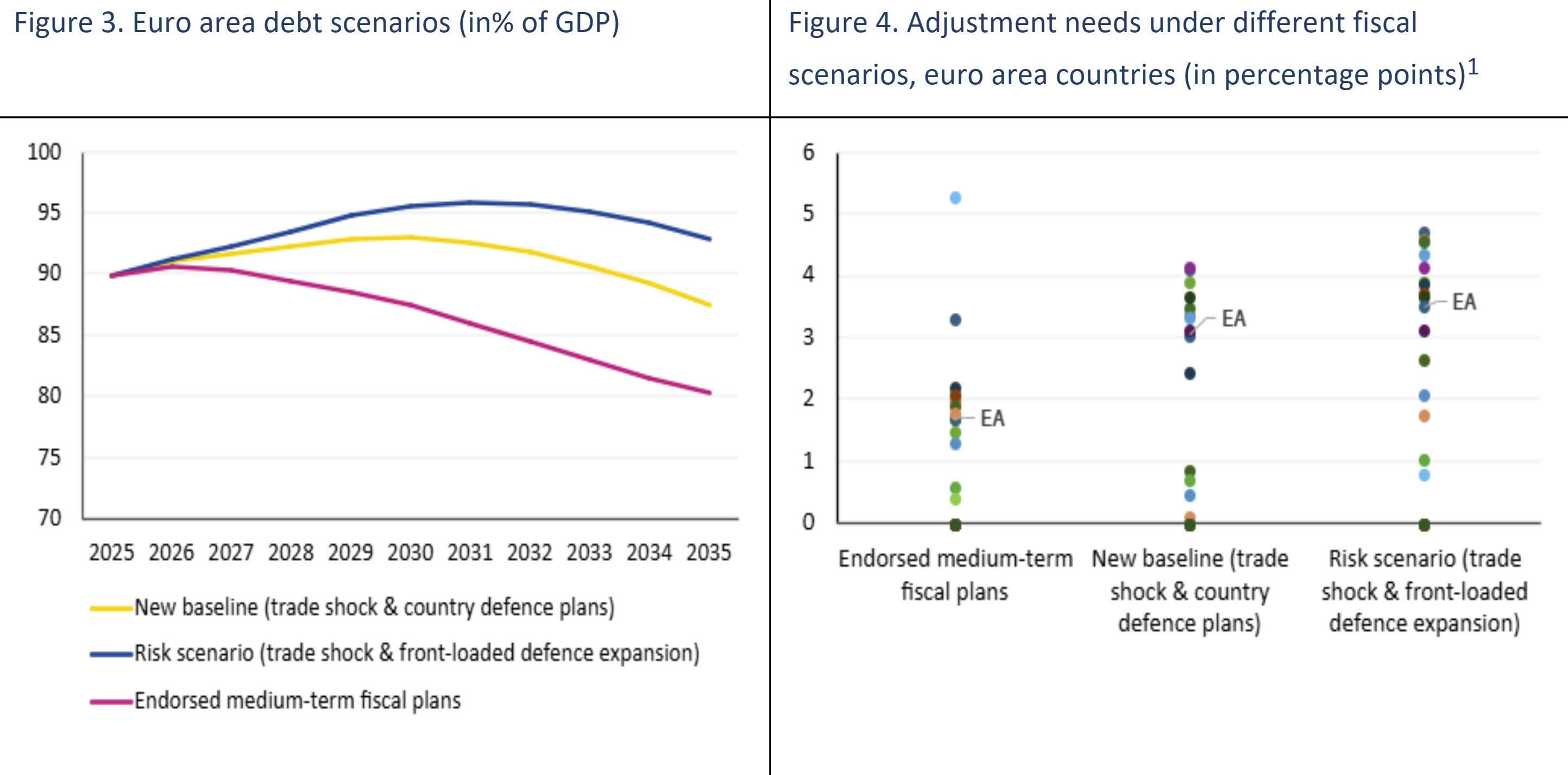

EU Member States had agreed on a medium-term fiscal trajectory with the European Commission based on net expenditures. But changes in growth and the combined impact of trade barriers and higher defence spending will lead to higher debt trajectories, a more protracted reversal, and bigger fiscal adjustment needs.

As illustrated in Figure 3, a deficit financed increase of defence spending fully exploiting the leeway created by national escape clauses would lead to a significant upward shift of debt above the current levels within a decade. This implies significantly less fiscal space to counteract downturns. The additional adjustment required if countries use this flexibility is substantial (see Figure 4). For many countries it exceeds the maximum fiscal consolidation achieved over recent decades. Therefore, it will be important to re-prioritise spending early on and limit the degree to which the fiscal leeway under the escape clauses is actually used.

Policy response – the challenge ahead

In previous columns, I have discussed the policy challenges and trade-offs in attaining growth and strategic autonomy and strengthening economic resilience. I have asked for a nimble policy framework.[2] The developments over the past months have reinforced the case for a framework that helps guide and anchor market expectations and generate private sector financing.

Current market optimism entails the inherent risk of price adjustment when expectations are not met. Having clear plans how to support growth and ensure debt levels in highly indebted countries can be brought down, help to anchor expectations.

Governments finance defence. This is not a task which could be shifted to the private sector. With agreement on very ambitious spending targets, governments need to re-prioritise spending, find private funding sources for competing spending pressures, or generate fiscal space at the European level. This expenditure shift may need to happen rather sooner than later.

The current environment underscores the need to fast-track progress on savings and investments union (SIU). The European Commission has in fact decided to front-load all proposals – recommendations, directives, and regulations – to implement SIU. Progress in the proposed legislation and action plans requires substantive national buy-in as key responsibilities are at the national level (for example for a capitalised pension pillar), and giving up national prerogatives to build a truly common market is a tough ask. The countries would also need to go along with the simplification objective put forward for financial regulation and supervision.

When the SAFE instrument’s envelope will be exhausted, the European Commission envisages the potential for innovative options, including the use of the ESM.[3] The proposed Multiannual Financial Framework also foresees appropriations that can be used for this purpose and overall implies a more flexible and growth-oriented use of the European budget. This is a big step forward, although the International Monetary Fund suggests that a larger budget will be needed to finance the necessary European public goods. Europe will need to mobilise available resources and be nimble and creative to maintain its resilience.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Giovanni Callegari and Ermal Hitaj for their valuable suggestions and contributions to this blog post, CED team for data and Raquel Calero for the editorial review.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Author

Blog manager