Explainer on ESM and EFSF financial assistance for Greece

Overview

Three financial assistance programmes were needed for Greece – why so many?

The extent of underlying economic problems at the beginning of the crisis in Greece was much greater than in other ESM/EFSF programme countries. Having adopted the euro in 2001, Greece was able to borrow at low interest rates despite its falling competitiveness and weak public finances. While government spending and borrowing increased, tax revenues weakened due to poor tax administration. Public debt soared quickly and investor trust in Greece was seriously undermined. The Greek economy contracted sharply (nearly 30% from 2008 to 2016) and unemployment climbed to alarming levels. Furthermore, the country’s administration was weaker than in other euro area countries. The public sector was oversized and its efficiency was well below European standards.

During the first and second programmes (bilateral loans from the other euro area countries known as the Greek Loan Facility or GLF from 2010-2011; EFSF programme from 2012-2015), wide-ranging reforms were carried out to address Greece’s problems, and in 2014, the country recorded GDP growth for the first time since 2007 and unemployment began to fall. In the first half of 2015, the country reversed very important reforms. There was an attempt to halt the reform programme Greece had agreed to. The result was that the country dropped back into recession. The third programme, agreed with the ESM in August 2015, enabled Greece to remain in the euro area in return for implementing a series of much-needed reforms. After three years, on 20 August 2018, Greece successfully completed the ESM programme. As of this date, the country is no longer reliant on ongoing external rescue loans for the first time since 2010.

What is the total amount of loans that Greece received over the three programmes?

Greece has received a total of €288.7 billion in rescue loans since 2010. The details are shown below:

Euro area, EFSF/ESM and IMF assistance for Greece

| Financial assistance programmes for Greece | Disbursed (€ billion) | |

| 1st programme | GLF (euro area)

IMF Total |

52.9

20.1 73.0 |

| 2nd programme | EFSF

IMF Total |

141.8

12.0 153.8 |

| 3rd programme | ESM | 61.9 |

| Total from euro area, EFSF and ESM

Total from IMF Total loans disbursed |

256.6

32.1 288.7 |

|

The total amount disbursed by the EFSF and the ESM to Greece is €203.77 billion.

When will Greece repay the ESM and EFSF loans?

Greece will repay the ESM loans from 2034 to 2060. The EFSF loans are currently scheduled to be repaid from 2023 to 2056, but according to the medium-term debt relief measures politically approved by the Eurogroup in June 2018, there will be an extension of the maximum weighted average maturity by 10 years on €96.4 billion of EFSF loans. This extension requires approval by the EFSF Board of Directors.

Is Greek debt sustainable?

The implementation of an ambitious growth strategy and prudent fiscal policies by the Greek government will be the key ingredients for debt sustainability. Through its long-term growth plan, Greece is committed to preserving its programme achievements, which includes completing the reforms that were enacted under the programme and continuing to implement further reforms designed to boost its growth potential.

In addition, the Greek government has committed to maintaining a primary surplus of 3.5 % of GDP until 2022, and around 2% in following years to continue to ensure that its fiscal commitments are in line with the EU fiscal framework.

Finally, the medium-term debt measures agreed by the Eurogroup, together with the significant cash buffer available to the Greek government, will provide strong support for Greece’s efforts. The European institutions’ Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) indicates that Greece’s gross financing needs are expected to remain below 15% of GDP over the medium term and to comply with the 20% threshold in the long run, and that Greece’s debt is therefore considered sustainable.

For the long-term, the Eurogroup also agreed to review at the end of the EFSF grace period in 2032, whether additional debt measures are needed to ensure the respect of these gross financing needs targets. However, additional measures can only be considered if Greece continues to respect the EU fiscal framework.

ESM Programme (2015-2018)

How much did the ESM disburse?

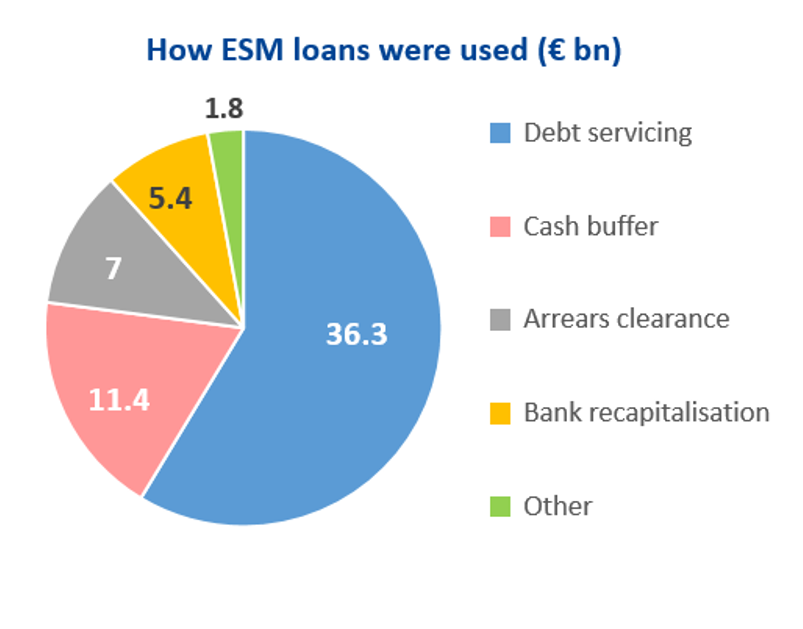

The ESM disbursed a total of €61.9 billion, out of a maximum programme volume of €86 billion. The unused amount mainly derives from the substantially lower recapitalisation needs of banks compared to what was originally foreseen (€5.4 billion used out of a maximum amount of €25 billion) and from more efficient management of cash resources by the Greek government.

It should be noted that in the ESM programmes for Spain and Cyprus, the amount disbursed was also lower than the maximum amount available under their respective programmes.

How were the funds used by Greece?

The chart below provides a breakdown of how the ESM loans were used by Greece:

Why was bank recapitalisation part of the Greek ESM programme?

Due to political uncertainty and fear of a Greek euro exit, deposit holders withdrew significant funds from Greek banks in 2015, and the banks experienced an increase in payment delays as borrowers waited to see whether the government would introduce debt relief measures.

Under the programme, the ESM committed up to €25 billion to Greece to address potential bank recapitalisation and resolution costs. In December 2015, the ESM disbursed a total of €5.4 billion to the Greek government for the recapitalisation of Piraeus Bank and NBG.

What commitments has Greece entered into?

Greece has committed to maintain a primary surplus (a national government’s budget surplus excluding interest payments on its outstanding debt) of 3.5% of GDP until 2022 and, thereafter to ensure that its fiscal commitments are in line with the EU fiscal framework (around 2%).

Further commitments are described in What challenges does Greece still face?

What kind of surveillance will Greece be subject to now the programme is over?

The European Commission activated the Enhanced Surveillance framework, which implies quarterly reports of the Commission to assess its economic, fiscal and financial situation and the post-programme policy commitments. Enhanced surveillance is appropriate due to the large amount of money disbursed by the EFSF/ESM and the unprecedented debt relief. The ESM will closely collaborate with the Commission in the post-programme phase in the context of its Early Warning System.

How does the ESM Early Warning System work with regard to Greece?

With a combined €190.8 billion in outstanding loans to Greece, the EFSF and the ESM are by far the country’s largest creditors. This is an amount higher than Greece’s projected GDP in 2018. The rescue funds together hold a total 55.5% of Greek central government debt.

In order to ensure that Greece and other beneficiary countries repay their loans, the ESM is obliged by the ESM Treaty to carry out its own monitoring, called the Early Warning System (EWS), until the loans have been repaid in full. This requires an assessment of the country’s short-term liquidity, market access, and the medium- to long-term sustainability of public debt.

How does Greece achieve budgetary savings thanks to ESM and EFSF loans?

The ESM and EFSF have provided loans to Greece at much lower interest rates and with exceptionally long maturities compared to those that the market would offer. These favourable lending terms have generated considerable budgetary savings, facilitating fiscal consolidation and/or tax cuts. The amount of savings is calculated by comparing the effective interest rate payments on ESM and EFSF loans with the interest payments Greece would have paid had it covered its financing needs in the market. In 2017 the savings amounted to €12 billion, or 6.7% of Greek GDP. The savings take effect at similar level every year.

Reforms

What progress has the Greek economy made since 2010?

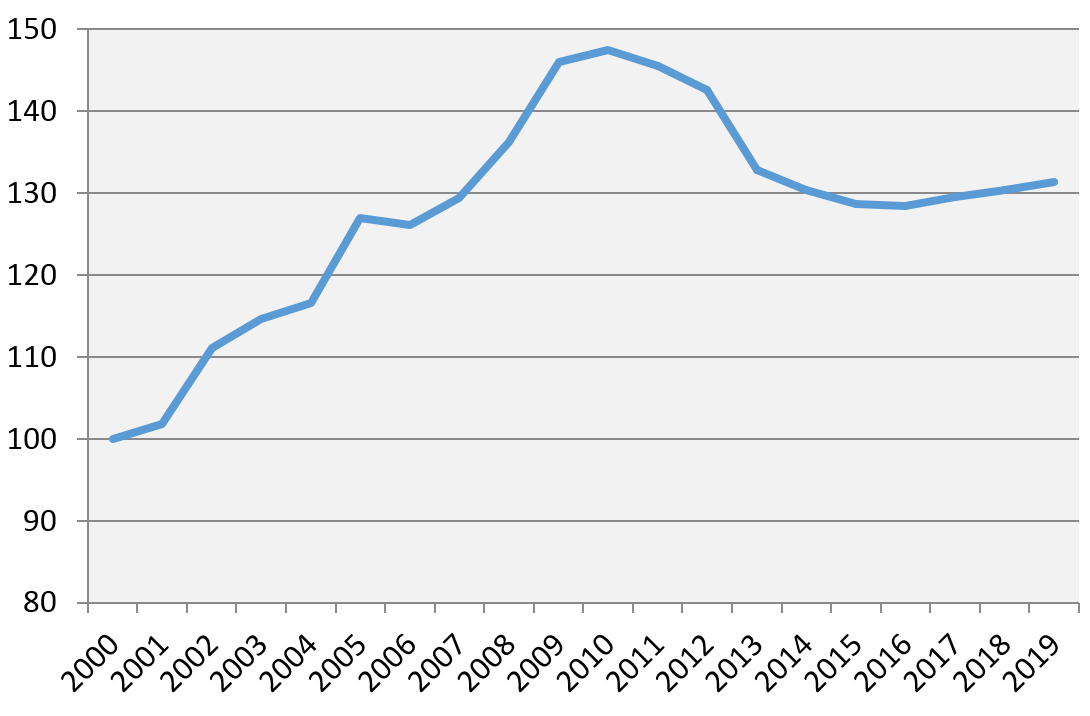

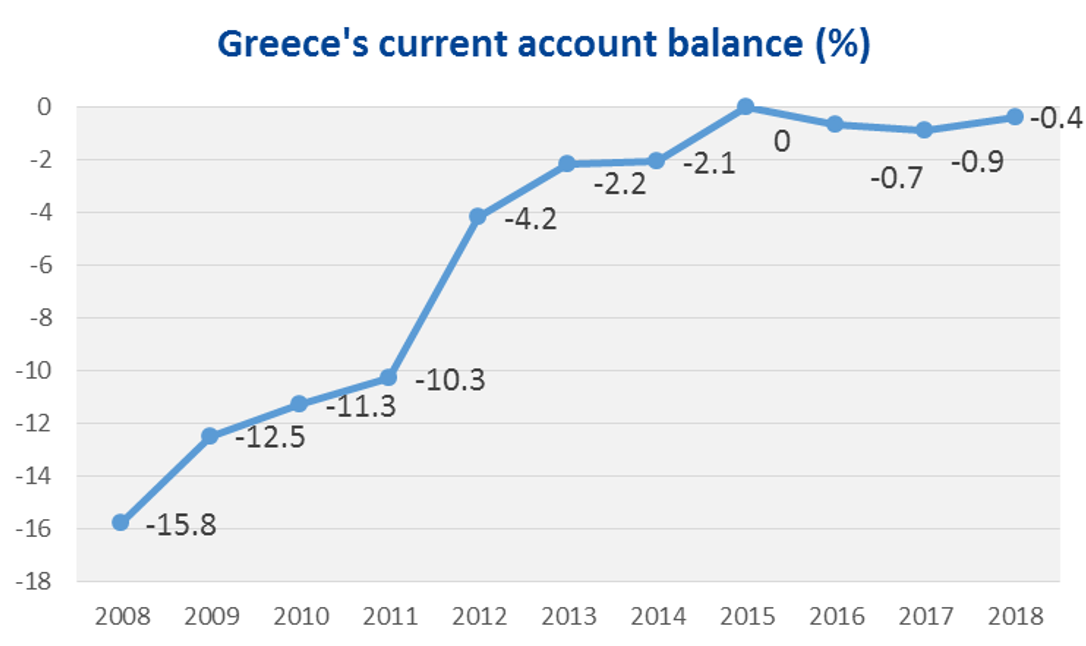

Greece has managed to significantly reduce its macroeconomic and fiscal imbalances. An unprecedented fiscal adjustment has resulted in a decline of the general government deficit by roughly 16 percentage points of GDP, to a surplus of 0.8% in 2017 from a deficit of 15.1% in 2009. Economic growth has returned as the recovery has begun to take hold, rebounding from -5.5% in 2010 to 1.4% in 2017. The Greek economy has improved its competitiveness by reducing unit labour costs.

Nominal unit labour costs in Greece (2000=100)

The improvement can also be seen in the falling current account deficit: to -0.4% in 2018 from -15.8% in 2008.

Greece’s current account balance 2007-2018

Source: European Commission

In 2010 unemployment was at 12.7%. After reaching a peak of 27.5% in July 2013, it has now decreased to 19.5% in May 2018. While unemployment is still the highest among all EU countries, labour market conditions continue to improve. The reduction in 2017 was the greatest single year decline since the peak in 2013. More than 100,000 new jobs have been created since the start of the ESM programme in 2015.

What kind of reforms have been implemented in Greece?

Since 2010, Greece has carried out a comprehensive range of reforms, which can be grouped into four areas (the most important examples are listed):

- Restoring the sustainability of public finances

- Personal income tax system revised

- VAT system streamlined for general efficiency and to reduce scope for fraud

- Unsustainable and fragmented pension system overhauled

- Safeguarding financial sustainability

- Governance of Greek systemic banks strengthened and brought in line with international best practice

- Structure of household and corporate insolvency legislation reviewed

- Reduction in stock of non-performing loans (NPLs)

- Structural policies to enhance growth, competitiveness and investment

- Labour market reforms – improved system of collective bargaining

- Product markets – reducing unnecessary barriers, lifting restrictions in regulated professions

- New independent fund (HCAP) for better management, improved service provision, and monetisation of key State assets

- Energy market for gas and electricity has been opened

- The functioning of Greece’s public sector

- Size of public sector reduced by 25% between 2009 and 2017

- Annual performance assessments for all public officials; competitive selection of senior management

- Reforms improving efficiency of judicial system

What challenges does Greece still face?

Although Greece’s achievements in rebounding from a deep crisis have been remarkable, significant challenges remain. Efforts must continue to liberalise the economy, create an effective public administration, as well as a business-friendly environment. Unemployment remains very high (19.5% in May 2018), and sustainable growth is the only way for Greece to deliver more jobs and prosperity for its people.

Greece needs to build upon the progress achieved under the ESM programme and strengthen the foundations for a sustainable recovery, notably by continuing and completing reforms launched under the programme. In an annex to the Eurogroup statement of 22 June 2018, the Greek government committed to ensure the continuity and completion of reforms in several key areas:

- Fiscal and structural (primary surplus of 3.5% of GDP over the medium-term)

- Social welfare (modernising pension and health care systems)

- Financial stability (continued reforms aimed at restoring the health of the banking system, including NPL resolution)

- Labour and product markets (action plan on undeclared work; investment licensing reform; completing the cadastre project)

- Hellenic Corporation of Assets and Participations (HCAP) and privatisation (asset development plan; completing key transactions)

- Public administration (modernising human resource management in the public sector; new labour law code; implementing anti-corruption recommendations).

Debt relief

What was the private sector debt restructuring in March 2012?

Also known as the PSI (private sector involvement) or private sector haircut, it was a restructuring of Greek debt held by private investors (mainly banks) in March 2012 to lighten Greece’s overall debt burden. About 97% of privately held Greek bonds (about €197 billion) took a 53.5% cut of the face value (principal) of the bond, corresponding to an approximately €107 billion reduction in Greece’s debt stock.

The EFSF encouraged bondholders to participate in the restructuring. It provided EFSF bonds as part of two facilities to Greece. These were the:

- PSI facility – as part of the voluntary debt exchange, Greece offered investors 1- and 2-year EFSF bonds. These EFSF bonds, provided to holders of bonds under Greek law, were subsequently rolled over into longer maturities.

- Bond interest (accrued interest) facility – to enable Greece to repay accrued interest on outstanding Greek sovereign bonds under Greek law which were included in the PSI. Greece offered investors EFSF 6-month bills. The bills were subsequently rolled over into longer maturities.

What measures were agreed by the Eurogroup to ease Greece’s debt burden in November 2012?

The Eurogroup agreed a set of measures designed to ease Greece’s debt burden and bring its public debt back to a sustainable path. These measures included:

- reducing the interest rate charged to Greece on the bilateral loans in the context of the Greek Loan Facility (GLF) by 100 basis points;

- cancelling the EFSF guarantee commitment fee of 10 basis points (it is estimated that this will save a total of €2.7 billion over the entire period of EFSF loans to Greece);

- extending the maturity of GLF loans by 15 years to 30 years (to 2041); extending the EFSF weighted average maturities by 15 years to 32.5 years, thus significantly improving the country’s debt profile;

- deferring interest rate payments on EFSF loans by 10 years until the end of 2022 (it is estimated that this will lower the country’s financing needs by €12.9 billion);

- passing on to Greece an amount equivalent to the income of the ECB’s Securities Markets Programme (SMP) portfolio accruing to their national central bank.

What potential measures were announced by the Eurogroup in May 2016?

In its statement of 9 May 2016, the Eurogroup informed that a package of debt measures for Greece could be phased in progressively, as necessary to meet the agreed benchmark on gross financing needs and subject to the conditionality of the ESM programme. The Eurogroup said it would consider short-, medium- and long-term debt relief measures, but nominal debt haircuts were excluded.

What were the short-term debt-relief measures implemented by the EFSF and ESM in 2017?

The ESM and EFSF Board of Directors approved a series of short-term measures for Greece in January 2017, which were implemented during the course of 2017:

- Smoothing the EFSF repayment profile (increasing the weighted average maturity of loans to 32.5 years from 28.3);

- Reducing interest rate risk for Greece:

- Exchanging EFSF/ESM floating-rate bonds for fixed-rate bonds; interest rate swaps; matched funding for future disbursements;

- Waiving the step-up interest rate margin for 2017 on an €11.3 billion EFSF loan tranche (margin of 2% had originally been foreseen).

Thanks to these measures, Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio will be reduced by an estimated 25 percentage points until 2060, and Greece’s gross financing needs will be lower by an estimated 6 percentage points over the same period.

What are the medium-term debt relief measures agreed by the Eurogroup in June 2018?

The Eurogroup politically approved three medium-term debt relief measures for Greece on 22 June:

- The abolition of the step-up interest rate margin related to the debt buy-back instalment of the second Greek programme as of 2018;

- The use of 2014 SMP (Securities Markets Programme) profits from the ESM segregated account and the restoration of the transfer of ANFA (Agreement on Net Financial Assets) and SMP profits to Greece (as of budget year 2017). These are profits acquired by national central banks and the ECB from holdings of Greek government bonds (purchased on the secondary market). The profits will be transferred to Greece in equal amounts on a semi-annual basis in December and June, starting in 2018 until June 2022. They will be used to reduce gross financing needs or to finance other agreed investments;

- A further deferral of interest and amortization by 10 years and an extension of the maximum weighted average maturity by 10 years on €96.4 billion of EFSF loans.

Measures I and II are subject to compliance with policy commitments and monitoring. The total package of medium-term debt relief measures will reduce the Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio by an estimated 30 percentage points by 2060, and the gross financing needs-to-GDP ratio by around eight percentage points. This comes on top of the already implemented short-term debt relief measures.

Will there be further (long-term) debt relief measures?

Based on a debt sustainability analysis (DSA) to be provided by the European institutions, the Eurogroup will review at the end of the EFSF grace period in 2032, whether additional debt measures are needed to ensure the respect of the agreed gross financing needs targets.

A contingency mechanism on debt could be activated in the case of an unexpectedly more adverse scenario. If activated by the Eurogroup, it could entail measures such as a further re-profiling and capping and deferral of interest payments to the EFSF to the extent needed to meet the gross financing needs benchmarks of 15 to 20% of GDP.

The first and second Greek programmes (2010-11; 2012-15)

What led to Greece’s economic problems?

After Greece adopted the euro in 2001, it was able to borrow at much lower interest rates despite its deteriorating competitiveness and public finances. In the decade before the crisis, Greece was able to use this cheap funding to finance a deficit which grew to unsustainable levels. Conditions in the euro area during this period facilitated such lending, despite the build-up of the unsustainable deficit. This meant that Greece could delay difficult structural reforms that had become necessary and may have been unavoidable if cheap funding had not been available during the 2000s.

While government spending and borrowing increased, tax revenues weakened due to poor tax administration. At the same time, wages rising much faster than productivity growth undermined Greece’s competitiveness, while low productivity and existing and significant structural problems also contributed to the increasing economic difficulties. As a result, Greece’s economy contracted and unemployment began to climb to alarming levels.

Greece’s reliance on external financing for funding budget and trade deficits left its economy very vulnerable to shifts in investor confidence. In 2009, the Greek government revealed that previous governments had been misreporting government budget data. Much higher-than-expected deficits eroded investor confidence, causing the yields on Greek sovereign bonds (which correspond to the cost of borrowing money) to rise to unsustainable levels. The situation worsened to the point where the country was no longer able to refinance its borrowing, and it was forced to ask for help from its European partners and the IMF.

What is the Greek Loan Facility?

The Greek Loan Facility is the first financial support programme for Greece, agreed in May 2010. It consisted of bilateral loans from euro area countries, amounting to €52.9 billion, and a €20.1 billion loan from the IMF. The EFSF, which was only established in June 2010, did not take part in this programme.

Why did Greece need a second programme in 2012?

Greece made major efforts to implement wide-ranging reforms, which were tied to the first financial assistance package. The challenges confronting Greece remained significant, however, with a wide competitiveness gap, a large fiscal deficit, a high level of public debt, and an undercapitalised banking system. The economic recession in Greece proved to be more serious and damaging than expected. The financial assistance provided under the first programme was not sufficient for Greece to make the necessary adjustments and to regain market access.

Furthermore, Greece’s public debt was considered unsustainable. A restructuring of debt held by private creditors became necessary to bring the total debt level back to a sustainable path. Additional time and funds were required to Greece’s fiscal consolidation efforts with structural reforms, to boost growth, and improve competitiveness. Therefore, a second programme for Greece, provided by the EFSF and IMF, was decided in February 2012.

How much did the EFSF provide to Greece?

The EFSF disbursed €141.8 billion in loans to Greece from 2012 to 2015. The EFSF programme was part of the second programme for Greece. The IMF contributed €12 billion in loans under the programme.