Stronger fundamentals, new challenges: Greece's sovereign debt

Following years of fragmentation after the euro sovereign debt crisis, European bond markets have reintegrated since 2019. For countries like Greece, integration is a major success, bringing favourable financing conditions, but also new risks.

During the crisis, Greek sovereign yields soared above those of European peers as government bond markets fragmented. In recent years, Greece’s sovereign yields have converged with many of its peers, reflecting the strong recovery of the Greek economy and fiscal surpluses. This suggests that Greek and highly-rated European sovereign bonds are once again perceived as substitutes, signalling a renewed integration of bond markets. This renewed integration exposes Greece to different spillovers from abroad. For instance, the German fiscal expansion announced in March 2025 raised yields not only in Germany but also by a similar magnitude in Greece, highlighting the need to continuously monitor evolving risks to sovereign financing conditions.

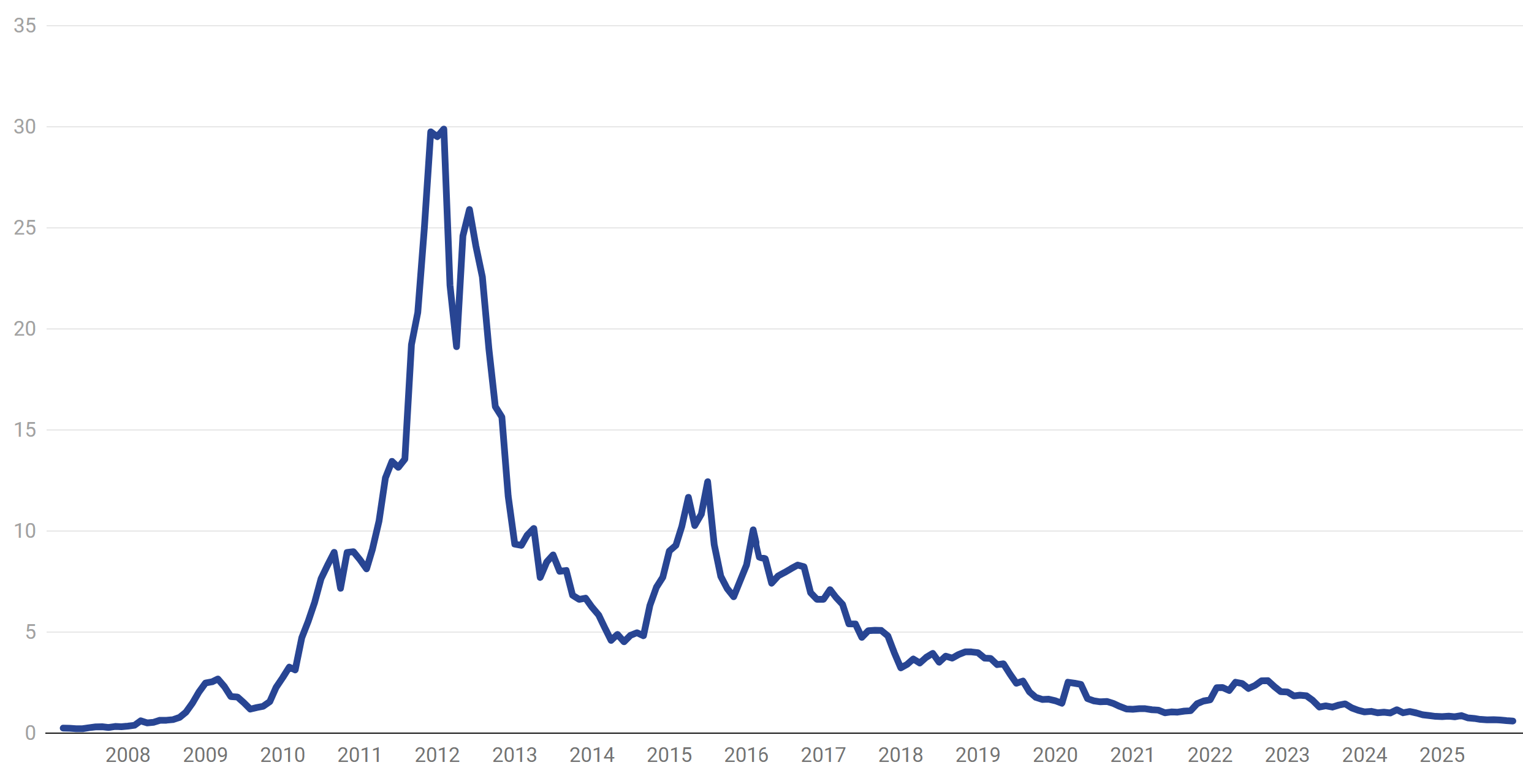

Greece’s sovereign spread falls to pre-crisis levels

As of May 2025, the Greek sovereign spread (the 10-year yield differential in relation to the German Bund – the euro area’s sovereign benchmark bond) fell below 80 basis points for the first time since 2007 (Figure 1).

In 2007, at the onset of the global financial crisis, concerns emerged about the sustainability of public finances in several euro area countries, including Greece. As a result, Greece’s sovereign spread began to widen. This reflected investors’ growing demand for a higher risk premium to hold Greek government bonds. While the spread had hovered around 25 basis points in early 2007, it rose sharply over the course of the year, surpassing 80 basis points in October that year marking the change in risk sentiment (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The Greek sovereign spread has fallen to pre-crisis levels

Difference in 10-year sovereign yield against Germany

(in percentage points)

Click here to expand 2018 - 2025 ▼

Source: ESM calculations based on Bloomberg data

As concerns about public finances intensified, sovereign spreads continued to widen, and European sovereign bond markets became increasingly fragmented. That is, government bond yields diverged between countries perceived as safe borrowers and those viewed as having elevated default risk. [1] These developments culminated in the euro sovereign debt crisis. Prior to the crisis, the market for European sovereign bonds was highly integrated because all bonds were perceived as close substitutes and therefore traded at similar yield levels and, thus, also moved largely in parallel.

During the crisis, Greek sovereign spreads rose to levels that effectively cut Greece off from sustainable market-based financing. Ultimately, Greece received financial assistance, including from the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

Since Greece completed its third financial assistance programme in 2018, however, the Greek spread has declined markedly. This decline reflects the strong recovery of the Greek economy, with robust gross domestic product (GDP) growth, sustained fiscal surpluses, and a decisively declining debt-to-GDP ratio since 2021. [2] The compression of the spread indicates that investors once again perceive Greek and other highly-rated European sovereign bonds as close substitutes. This suggests, in turn, that bond markets are again more integrated after years of fragmentation.

Renewed integration of Greek and European debt markets brings increased spillovers effects

Integrated sovereign bond markets are characterised not only by narrow spreads, but also by strong spillovers across countries. [3] Market integration implies that investors perceive bonds issued by different sovereigns as close substitutes and are therefore willing to reallocate their portfolios between them. As a result, an increase in the yield of one bond attracts demand away from other bonds, putting upward pressure on their yields as well. Such spillover effects provide the most concrete evidence of market integration.[4]

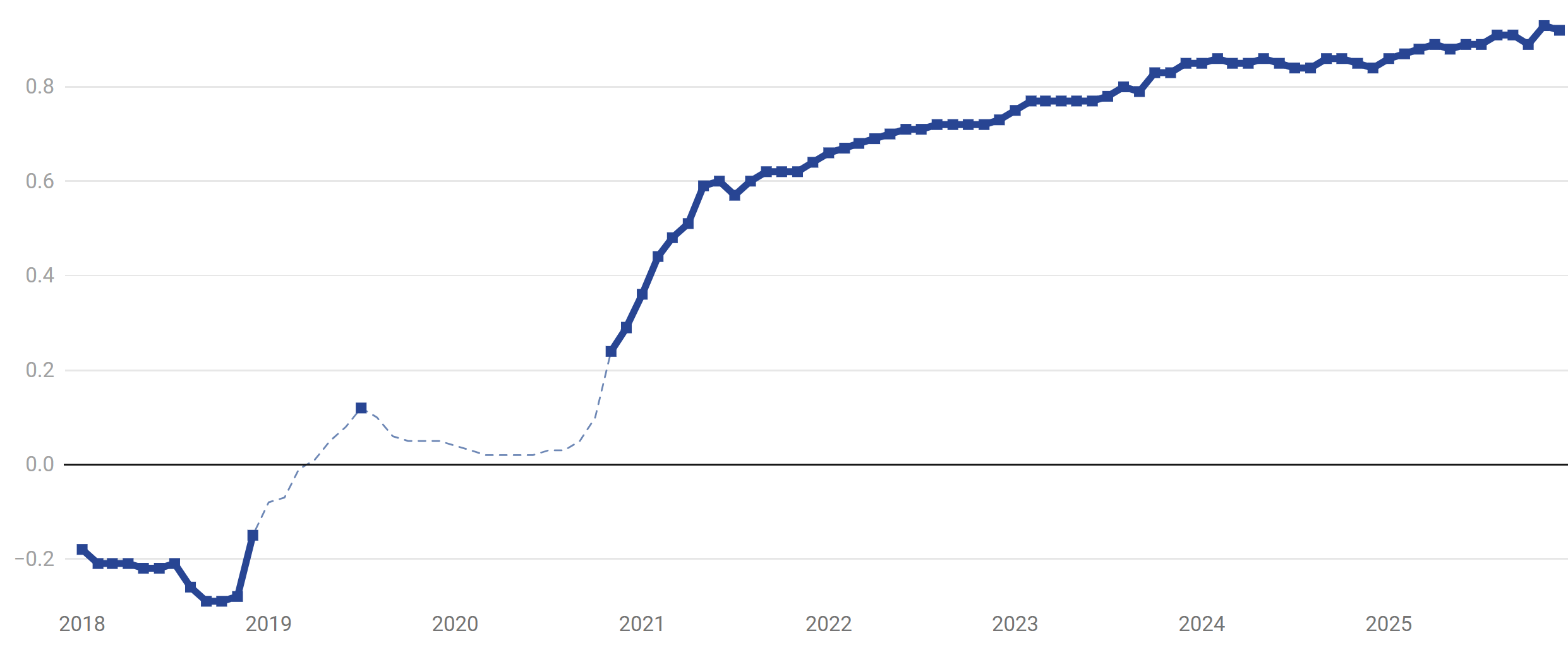

We find three pieces of evidence that show that spillovers between Greek and German government bonds (often considered the sovereign benchmark bond for the euro area) have increased over time.

First, changes in Greek yields have become increasingly correlated with changes in German yields (Figure 2, panel a). While this correlation was negative in 2018, it has since turned positive. [5] Thus, an increase in the German yield used to be associated with a decrease in the Greek yield. Now, whatever moves the German yield increasingly also moves the Greek yield in the same direction.

Figure 2

Spillovers between Greek and German sovereign yields have risen

a) Correlation: Greek and German 10-year yields

Note: Rolling-window correlations of daily changes in 10-year yields. Square markers denote coefficients significantly different from 0 (95% significance level).

b) Spillover from German debt issuance to Greek yields

Note: Rolling-window relative change in the Greek 10-year yield relative to the change in the German 10-year yield in a 30-minute window around announcements by the German debt management office. Square markers denote coefficients significantly different from 0 (95% significance level).

Source: ESM calculations based on Bloomberg data

Second, we find that news about German sovereign debt issuance increasingly affects Greek yields (Figure 2, panel b). These spillovers are estimated as yield co-movements around announcements on German debt supply by the German debt management office, based on the methodology described in ESM Working Paper No. 63. Such spillovers were not detectable prior to 2020–2021, in line with the interpretation that markets were fragmented. Since then, these spillovers have become meaningfully positive and statistically significant. This shows that when investors are offered additional German debt at higher yields, they also demand higher yields on Greek bonds, providing clear evidence of substitutability across bonds and renewed market integration.

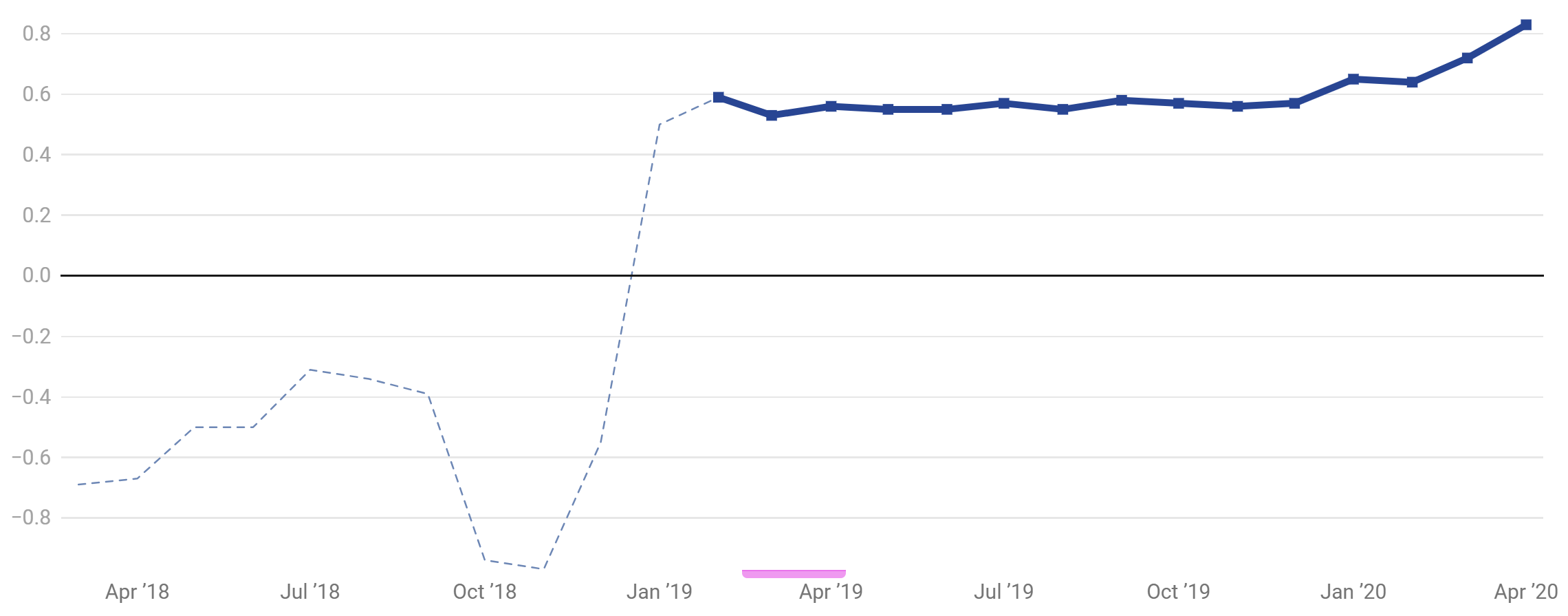

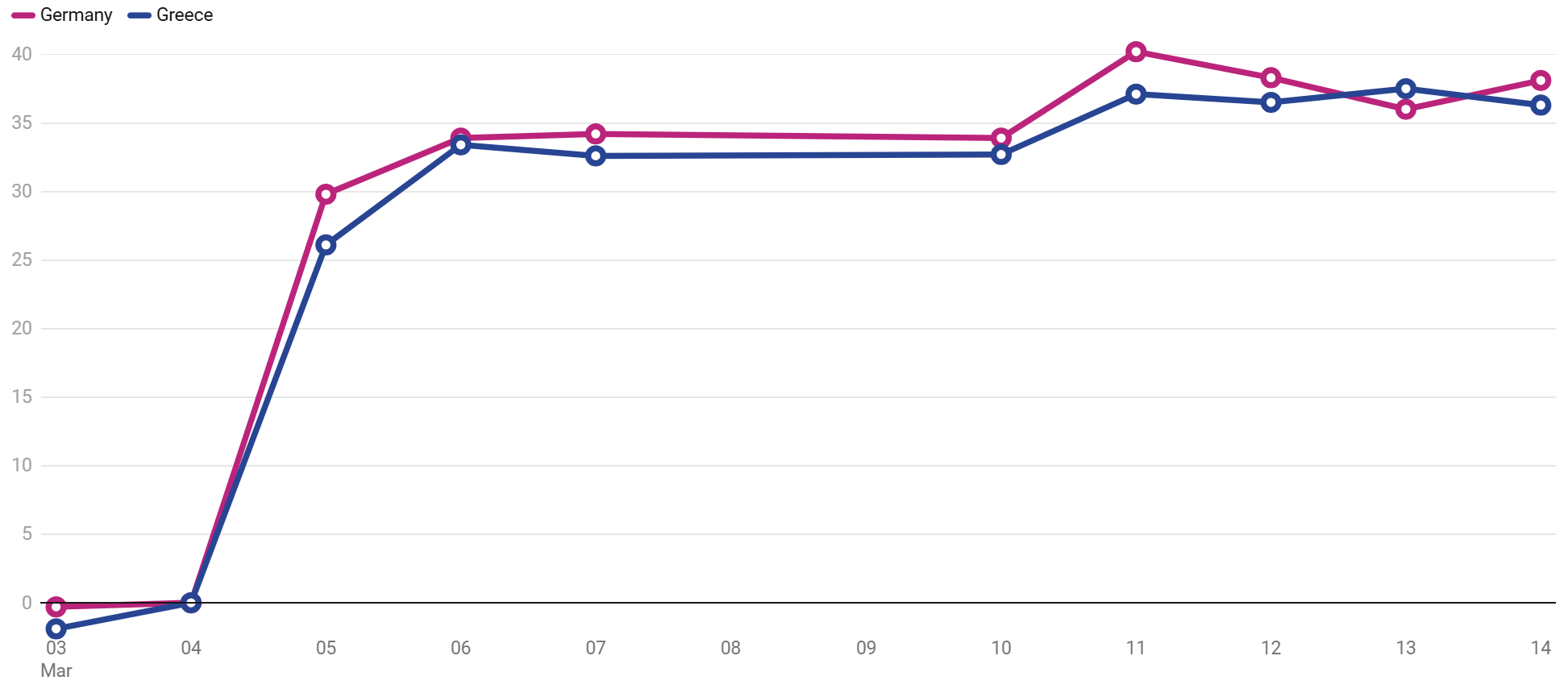

Third, the sizeable spillover effects that German debt issuance has today on Greek yields are further illustrated by market reactions to the 4–5 March 2025 announcement of a large fiscal expansion in Germany. The announcement led to a nearly 35 basis point increase in the German 10-year yield. The Greek yield rose by a very similar magnitude, underscoring the close link between the two markets (Figure 3).[6]

Figure 3

The German fiscal expansion had spillover effects on Greek yields

10-year sovereign yields, change versus 4 March 2025

(in basis points)

Source: ESM calculations based on Bloomberg data

Risks for Greek financing costs in the current environment

The benefits of a reintegration of Greek sovereign debt into the broader European bond market are clear: Greece can borrow and refinance its debt at favourable interest rates. At the same time, however, this reintegration also exposes Greece to new risks. Debt dynamics in core euro area countries now influence Greek yields as much as those of the issuing countries themselves.

Moreover, even though sovereign spreads have narrowed substantially, the risk of a renewed widening remains. A broad-based deterioration in euro area fundamentals could again lead investors to differentiate more strongly between sovereign issuers with higher and lower debt burdens. For instance, the 2 April 2025 tariff announcements from the United States triggered a marked, albeit short-lived, increase in sovereign risk premia and the spread of Greece compared to Germany. This episode underscores the importance of remaining vigilant. Even with the Greek spread at its lowest level in more than 15 years, maintaining prudent fiscal policies and further reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio are essential – while closely monitoring the evolving landscape of risks.

References

Arcidiacono, C., Bellon, M., & Gnewuch, M. (2024). Dangerous liaisons? Debt supply and convenience yield spillovers in the euro area. ESM Working Paper No. 63: WP 63.pdf.

Krishnamurthy, A., & Vissing-Jorgensen, A. (2012) "The aggregate demand for treasury debt." Journal of Political Economy 120.

Mankiw, G. (1998). Principles of Microeconomics. Elsevier.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Robert Blotevogel, Giovanni Callegari, Rolf Strauch and seminar participants at the Bank of Greece for their comments and valuable discussions to this analysis, and Raquel Calero for the editorial review.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Author

Blog manager