Building resilience through policy: The role of social safety nets

Building robust social safety nets during calm times can ease strain for the most vulnerable during crises. When policymakers work to reduce high public debt, social safety nets are an essential consideration. The euro area sovereign debt crisis exposed deep-rooted policy vulnerabilities and economic imbalances. Restoring fiscal soundness and market trust in government policies involved unpopular budget cuts, resulting in a complex undertaking with profound social consequences. Our research demonstrates the critical role of well-established safety nets in mitigating the negative impact of crises and macroeconomic support programmes on household incomes. A well-defined social safety cushion can better limit the costs of economic adjustments for vulnerable groups during crises.

Inequality in times of crisis

As a crisis resolution mechanism, the ESM plays a crucial role when markets question the financial stability of the euro area or its members. During crises, financial markets can doubt government policies and their capacity to repay debts by pressing the governments to reassess their policies. Governments needed to conduct macroeconomic adjustments that required fiscal savings to regain stable market access during the euro area debt crisis. Unpopular budgetary cuts can transform crisis resolution into a complex political, social, institutional, and economic endeavour beset by domestic challenges.

One of the key lessons learnt from the biggest financial assistance package provided during the euro area sovereign debt crisis[1] is that sustainable fiscal adjustment requires more equitable distribution of adjustment costs. A more holistic and long-term approach would prevent the deepening of social inequalities and help secure broad-based support for necessary reforms. It would also facilitate the tasks faced by the policymakers by alleviating pressure on the most vulnerable during the downturn.

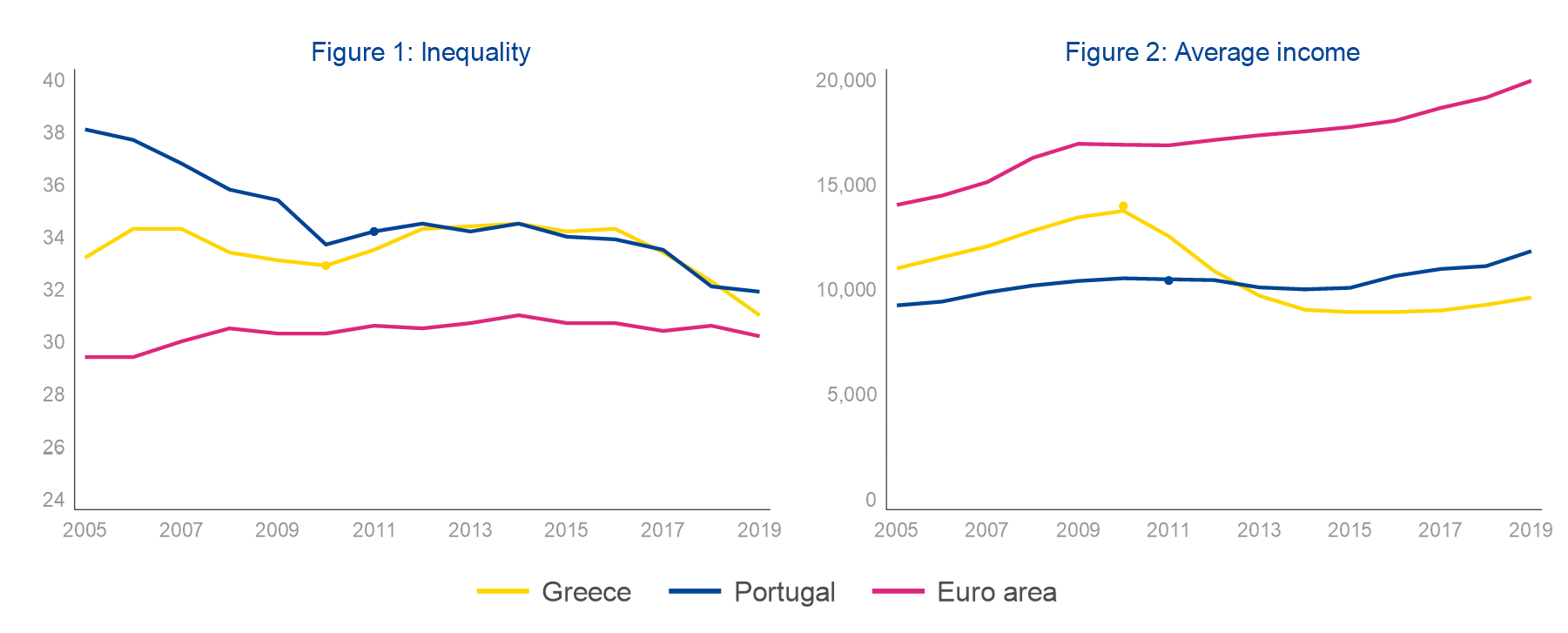

To understand what drove the rise in inequality during the sovereign debt crisis, our research[2] zooms in on how the crisis affected different income groups in Greece and Portugal, including the role played by social safety nets. Our analysis of household income dynamics helps us draw policy lessons beyond those one can extract when looking at aggregate indicators. The prominent and widely accepted inequality measure, the Gini coefficient, shows a reversal of a decline in inequality trend in Greece at the start of the macroeconomic support programme, which then peaked around 2014. It only gradually returned to pre-crisis levels after 2016. In Portugal, the inequality showed only a minimal uptick after the start of the economic adjustment programme and the earlier decline in inequality resumed already in 2014 (see Figure 1). While useful for cross-country and overtime comparisons, such a snapshot fails to capture the complexity of the macroeconomic support programme and the underlying drivers of inequality. Similarly, the significant drop in average household income conceals important distributional challenges faced by different income groups, particularly in Greece (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 and 2: Evolution of the Gini index including social transfers over time and household income

Notes: Figure 1 shows the Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income after all social transfers. Figure 2 reports the average equivalised disposable income. The dots indicate the start of the financial support programme.

Sources: Eurostat and EU–SILC

Granular data display social vulnerabilities

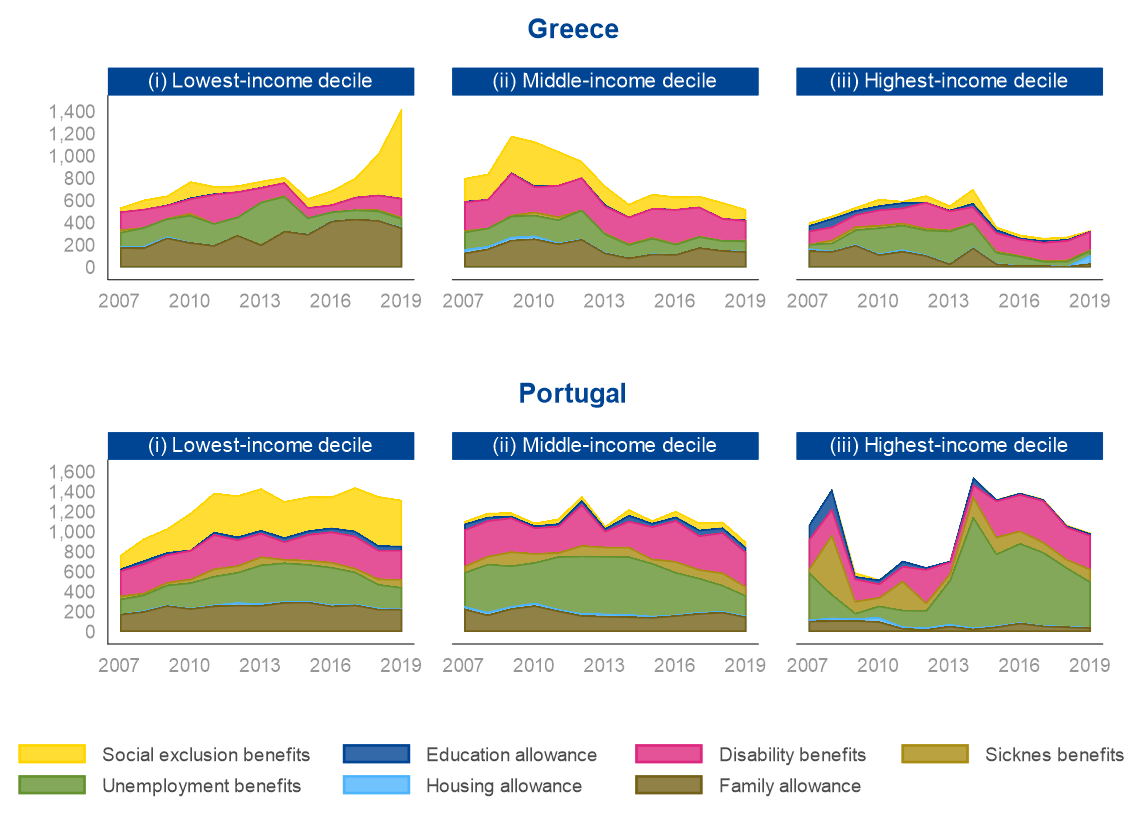

By differentiating social transfer income from labour and market income, and comparing the cases of Greece and Portugal, we can better understand the role of social safety nets in the evolution of income and inequality during the sovereign debt crisis (see Figure 3). Social safety nets and automatic stabilisers[3] should shield the most vulnerable during an economic downturn, yet the data uncover pre-existing gaps in these systems and several pre-crisis vulnerabilities. In Greece, for example, safety nets did not automatically provide adequate support,[4] while in Portugal the social system provided a more targeted and robust shield.

Figure 3: Social transfers over time

Notes: The figure reports breakdown of social benefits (social exclusion, family-/children-, housing-, and education-related allowances; unemployment, sickness and disability benefit, excluding the old-age and survivors' benefits) grouped by decile. The reference period is starting in 2007.

Source: EU-SILC

Social exclusion benefits are usually geared towards preventing poverty for the lowest-income households. In Greece, there is evidence that the pre-crisis social exclusion benefits lacked targeting, being distributed not only to low-income households but also to middle- and high-income groups (see Figure 3). In contrast, Portugal’s social safety net mostly supported the bottom 10% of households and provided a stable income throughout the crisis. Greece shifted its strategy towards the end of its financial assistance programmes, with an increase in income for the lowest-income households coinciding with the gradual rollout of its Social Solidarity Income scheme in 2016–2017.

Unemployment benefits are key in shaping household income during crises when replacing labour income. Here again Portugal and Greece differ. Acting as automatic stabilisers since the onset of the crisis, unemployment benefits played more of a social safety net role in Portugal. The unemployment benefits remained relatively stable throughout the crisis, providing a cushion against the negative impact of the economic adjustments on household incomes. In Greece, unemployment support remained comparatively less important and stable. For example, in 2014, the average annual unemployment benefits received by middle-income households was nearly five times higher in Portugal than in Greece. Limited coverage[5] and lower amounts translated into more significant financial strain for Greek households.

Greece and Portugal also approached family allowances differently. In Greece, family allowances were distributed across all income groups, with the highest-income families continuing to benefit from the outset and throughout most of the financial assistance period. In Portugal, family allowances remained comparatively low, with the higher-income groups receiving fewer benefits, particularly after the 2010 reforms that tightened the income-related eligibility criteria.[6] The comparison shows how better targeted support could have alleviated financial challenges for low-income households as well as fiscal pressures.

Policy analysis based on microdata highly relevant for fiscal decisions

The microdata reveal the value of well-established safety nets in mitigating the negative impact of macroeconomic support programmes on household income. We suggest that a targeted and flexible safety net can be well-suited to helping assuage painful economic changes. Currently, social protection expenditures represent around 20% of euro area gross domestic product (GDP) and are vital in supporting the population during economic distress.

While the pandemic and energy crises have increased public debt and put pressure on reducing social expenditures, any adjustments to existing social safety nets should be done cautiously. Building a strong safety net during non-crisis periods can help policymakers avoid ad hoc changes triggered by limited fiscal space and rising debt-to-GDP ratios during stress episodes. Policy and implementation errors under market stress can extend adjustment periods, raise funding requirements, and increase social costs. Such microeconomic analysis can help policymakers design policies geared towards the protection of the most vulnerable social groups, invaluable for the policy agenda regardless of the circumstances.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Pilar Castrillo, Cedric Crelo, Valentin Lang, Nicoletta Mascher, Rolf Strauch and Konstantinos Theodoridis for the valuable discussions and comments to this blog post, and Raquel Calero for the editorial review.

Further reading

Matsaganis, M. (2020). Safety nets in (the) crisis. The case of Greece in the 2010’s. Social Policy and Administration. 54:587-598

OECD (2013), Greece: Reform of social welfare programs. OECD Public Governance Reviews. OECD Publishing.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager