Momentum Builds for Strong and Deep European Safe Assets - article in Intereconomics

Kalin Anev Janse (European Stability Mechanism), Roel Beetsma (University of Amsterdam; Copenhagen Business School)

“Momentum Builds for Strong and Deep European Safe Assets”

Intereconomics, January 2026

Volume 61, 2026 · Number 1 · JEL: G15, F36, H87

An enlarged EU budget is needed with own resources to finance European public goods and create a savings and investment union. This article argues that Europe’s weak productivity, strategic vulnerabilities and fragmented capital markets call for a coherent EU-level investment strategy. European public goods generate cross-border spillovers and long-term benefits that justify common financing and debt issuance. Expanding European safe assets would improve market stability and liquidity and help build a fully fledged savings and investment union. Although political resistance persists, shifting national positions indicate growing momentum. The article also highlights the importance of pension funding and institutional investors in supplying long-term risk-bearing capital to boost growth and competitiveness.

As argued in the report by Mario Draghi (2024), the European Union suffers from lagging productivity, hence declining competitiveness, resulting in a steady hollowing out of our economy and undermining the affordability of our social welfare system. Now, more than one year after the report, we can take stock of the EU’s responses to the report to date. Draghi (2025) himself is critical and argues that we have drifted even further from adequately addressing the EU’s ailments.

In this contribution, we argue that, to turn the tide, the EU needs a coherent economic-financial strategy, which comprises a combination of measures, with the effectiveness of each measure depending on the presence of the other measures. One is an increase in the EU budget to create room for much-needed investments. The EU needs not only more private investments in advanced technology and related infrastructure, but also more public investment. Investments at the EU level are necessary to finance European public goods (EPGs) that benefit multiple countries. Also, the EU needs to be able to issue debt to finance those investments. This is justified by the fact that multiple cohorts benefit from these EPGs, hence it is fair to spread the costs over these beneficiaries. This will create a “truly safe European asset” able to compete against German bunds and US Treasuries, once the outstanding amount of EU debt is large enough to ensure sufficient liquidity and the volume of EU own resources has been raised enough to ensure sufficient repayment capacity of the debt to exclude potential default. A truly safe European asset is to be distinguished from the supranational assets that are now referred to as European safe assets.

At this moment, Europe has, next to the national debt, four supranational EU International Securities Identification Numbers (ISIN) code issuers: European Commission, European Investment Bank (EIB), European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF). They are seen as European safe assets (Anev Janse, 2023). A truly safe European asset will also support the completion of the savings and investment union (SIU), which allows capital to flow towards those places and projects where the risk-return trade-off is most favourable. Below we discuss in detail current and expected developments in the volume of outstanding European safe assets (for which the political momentum seems to be strengthening) and the importance of growing the supply of capital available for long-term risk-bearing investments. An important contribution to the latter is a further development of pension funding.

On the need for European public goods

In principle, governments should only interfere with the economy when there is a private market failure. Otherwise, goods and services should be provided by the private sector, so as to ensure competition without disruption and to create the strongest possible incentives for their efficient provision and further innovation. The EU should only interfere with public good provision when there is a failure in the national provision of public goods on top of a market failure: when both private agents and national governments fail to provide goods or services that simultaneously benefit multiple EU member states, there is a case for the EU providing EPGs. These are public goods and services financed by EU common resources and delivered by the EU central level, either directly or through the national governments. In the words of Fuest and Pisani-Ferry (2019), EPGs can be defined as “policies and initiatives whose value to the citizens are higher when conducted at EU rather than at national level”.

There are many examples of potential EPGs: think of joint military facilities, hydrogen infrastructure, cross-border high-speed railways, collective enhancement of the capacity of the electricity grid, vaccine procurement, etc. On the one hand, arguments in favour of providing certain goods or services at the EU level are greater economies of scale and stronger cross-border spillovers of their provisions.[1] When decisions are made at the national level, these beneficial spillovers will not be internalised, adversely affecting the balance between the costs and benefits of these goods or services. Also, certain layouts may be too large and risky for individual countries to finance.[2] On the other hand, differences in national preferences and better information provision about the needs and most effective implementation of public goods speak in favour of providing such goods and services at the national level (see, e.g. Beetsma & Buti, 2024; Claeys & Steinbach, 2024; Wyplosz, 2024; Anev Janse et al., 2025). In other words, there is a balance to be found here in deciding at which level, national or EU, to organise the provision of specific public goods.

The road towards EPGs is fraught with political resistance. Even though the case for making certain investments at the EU level is a no-brainer from an overall welfare perspective, various countries are reluctant to collectively finance such investments. This is possibly because they fear they will have to contribute disproportionately to their financing, in particular when this would take place through an increased EU budget, to which richer countries contribute proportionally more. Hence, the question is how can EPGs that benefit everyone come into existence.

A potential stepping stone is the so-called Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI). This concept aims to internalise positive cross-border spillovers of investments. In the words of former European Commission Vice-President Vestager,

Our State aid rules on Important Projects of Common European Interest enable Member States and the industry to jointly invest in breakthrough innovation and infrastructure. They do so when the market alone does not deliver, because the risks are too big for a single Member State or company to take. And it has to benefit the EU economy at large. Following an extensive consultation process, we have made targeted changes to our rules to further enhance the openness of IPCEIs and facilitate the participation of small and medium-sized enterprises. (European Commission, 2021).

Conditions to qualify for support as an IPCEI include the need to provide an important contribution to EU objectives, the involvement of at least four member states, and the need for substantial co-financing by the companies receiving state aid. IPCEIs can help Europe achieve scale in sectors like innovative nuclear technologies. However, the IPCEI model is still essentially national in design and funding. Moreover, it addresses incentives for collaboration in the provision of private products.

The proposed new multiannual financial framework

The natural place to provide EPGs is on the initiative of the European Commission with financing coming from the EU budget. The latter has long hovered around 1% of EU aggregate gross national income (GNI), although during the post-pandemic period (2021-2026) it was expanded by around €800 billion in order to finance the recovery from the pandemic. In fact, NextGenerationEU (NGEU) amounted overall to 5.5% of EU GDP in 2021, hence around 1% per year for five years, which is the same order of magnitude as that of the annual contribution to the regular EU budget. The current multiannual financial framework (MFF) covers the period 2021-2027. Negotiations on the new budget will start before the current one expires. On 16 July 2025, the European Commission (2025) proposed a budget of €1763 billion in 2025 prices for the next MFF covering the years 2028-2034. This amounts to 1.26% of EU GNI. The current MFF foresaw spending of 1.13% of GNI over 2021-2027. The proposed new budget adds 0.11 percentage points to cover the servicing of the NGEU debt. While this in fact implies an absence of an overall increase in EU priorities compared to the 2021-2027 MFF agreement (which was effectively hollowed out by unforeseen high inflation), the proposed composition of the budget reflects a shift of priorities towards boosting productivity and resilience through an increase in spending on EPGs, industrial and defence sectors. It foresees a new European Competitiveness Fund of €400 billion that focuses on clean transition and decarbonisation, digital transition, health and biotech, and defence and space. Further, it foresees more flexibility across the budget, simplification and more harmonisation of EU financial programmes, national and regional partnership plans and a package of new own resources, comprising adjustments of the revenues generated by the Emissions Trading System (ETS), adjustment of the revenues from the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), non-collected e-waste, a tobacco excise duty and annual lump-sum contributions from large companies (corporate resource for Europe, CORE). However, the Commission’s EU budget proposal has met with fierce criticism, from, among others, party leaders in the European Parliament (Weber et al., 2025).3

The current multiannual financial framework (MFF) covers the period 2021-2027. Negotiations on the new budget will start before the current one expires. On 16 July 2025, the European Commission (2025) proposed a budget of €1763 billion in 2025 prices for the next MFF covering the years 2028-2034. This amounts to 1.26% of EU GNI. The current MFF foresaw spending of 1.13% of GNI over 2021-2027. The proposed new budget adds 0.11 percentage points to cover the servicing of the NGEU debt. While this in fact implies an absence of an overall increase in EU priorities compared to the 2021-2027 MFF agreement (which was effectively hollowed out by unforeseen high inflation), the proposed composition of the budget reflects a shift of priorities towards boosting productivity and resilience through an increase in spending on EPGs, industrial and defence sectors. It foresees a new European Competitiveness Fund of €400 billion that focuses on clean transition and decarbonisation, digital transition, health and biotech, and defence and space. Further, it foresees more flexibility across the budget, simplification and more harmonisation of EU financial programmes, national and regional partnership plans and a package of new own resources, comprising adjustments of the revenues generated by the Emissions Trading System (ETS), adjustment of the revenues from the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), non-collected e-waste, a tobacco excise duty and annual lump-sum contributions from large companies (corporate resource for Europe, CORE). However, the Commission’s EU budget proposal has met with fierce criticism, from, among others, party leaders in the European Parliament (Weber et al., 2025). [3]

Even if the proposed MFF were acceptable to all negotiating parties, the question is whether it is sufficient to meet the needs posed by the green and digital transitions and in view of the fact that various large investments are better done at the EU level than at the national level. The answer is no. The European Commission (2020) estimates that for the EU to meet its 2030 climate target requires annual investments of about 2% of EU GDP, of which 0.5%-1% of GDP would have to come from public investment (Pisani-Ferry et al., 2023). However, no estimates are available on which fraction would be best spent on EPGs. Given that much of the investment in infrastructure, such as for hydrogen and electricity, would benefit the entire EU, it is plausible that a large fraction of the estimated additional investment burden would best be undertaken at the EU level. In view of the fact that, from a political acceptance perspective, any scaling back of current spending programmes can only happen at a slow pace, the proposed budget would be too small to make these investments.

Coalitions of the willing

A practical way forward in the provision of EPGs would be through the collective provision of public goods by (varying) coalitions of willing countries that perceive sufficient benefit from providing these together. Typical examples would be a team-up in financing a cross-border high-speed railway, financing collective defence initiatives or the tighter integration of electricity grids. It would be easier to have the main beneficiaries join together in a small group than initiate such investments at the EU-level. Other countries can – at a later stage – join successful initiatives by coalitions of the willing.

Collective investments of this kind can be incentivised with co-financing by the EU, so as to induce participants to internalise the positive cross-border spillovers that extend beyond the coalition. However, such co-financing may not be acceptable to EU-sceptic countries. An alternative would be that members of a coalition of the willing issue debt to finance their collective public goods. The EU could then buy this debt on the secondary market financed by issuing EU debt. This would create a deeper, more liquid market for EU debt. It would also ease the financing of these collective public goods, as EU secondary market operations would support the demand for national debt issued to finance the collective public goods. The question remains, though, how to deal with such initiatives over the long run. An approach based on coalitions of the willing would be fine in some instances, but less suitable as a long-run solution in other cases, such as the formation of a common defence policy (Beetsma et al., 2025) or where network effects are particularly strong, as may be the case for a hydrogen infrastructure.

Savings and investment union and the financial landscape

An EU savings and investment union (SIU) will ensure that capital flows towards those investments that yield the best trade-off between expected return and risk. This will not only help to boost the risk-adjusted return on existing savings deployed in the EU, it will also bring savings of EU residents back from other parts of the world, especially the United States, and attract savings of citizens elsewhere in the world. In other words, the overall pool of savings for investments in the EU will expand.

Establishing a fully fledged SIU requires a multitude of measures, especially in terms of legal harmonisation across countries (see, e.g. ELEC, 2024). Some of these have already been agreed or completed, such as the European Single Access Point, the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive and Central Securities Depositories Regulation. Others still need substantial work, such as the harmonisation of insolvency legislation and a common EU-wide system for a withholding tax on dividends and interest. Following a call in the Letta (2024) report, the European Commission hopes to move forward with the so-called 28th regime “that would allow innovative companies to benefit from a single, harmonised set of EU-wide rules wherever they invest and operate in the single market, including any relevant aspects of corporate law, insolvency, labour and tax law” (Marcus & Thomadakis, 2025). With an increasing share of companies following the 28th regime, national legal regimes might be gradually driven out of existence.

Aside from the harmonisation of relevant corporate law, the functioning of the financial markets is of crucial importance to achieve a well-functioning SIU. Crucial is the creation of a deep market for European safe assets (sometimes referred to as Eurobonds), comparable to that of the US and with the same “functionalities” as US Treasury debt; and the reconfiguration of the “financial landscape” to expand the volume of long-term risk-bearing capital.

European safe assets

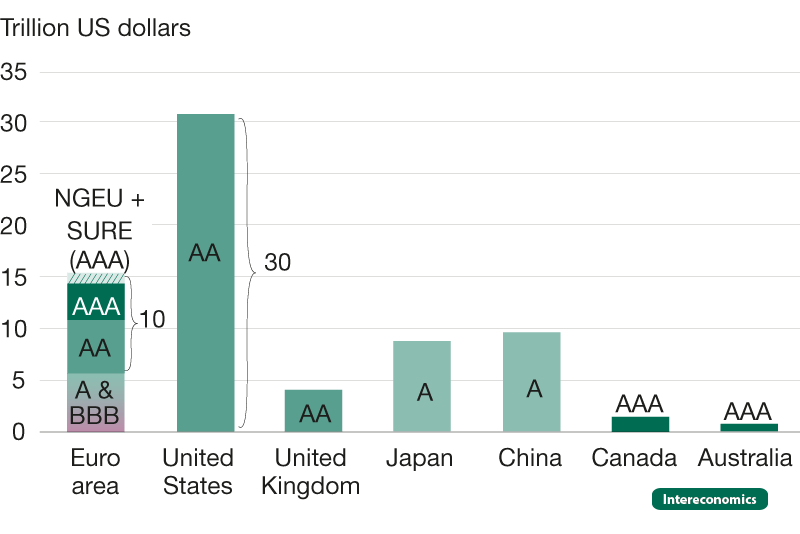

In times of market distress and rating downgrades, European safe assets are particularly crucial. French Governor Villeroy-de-Galhau (2025) showed in a recent speech that the volume of European safe assets (AAA-AA) is just one third compared to that of the US (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Relative scarcity of European safe assets compared to the US

Outstanding sovereign (and EU Commission) debt, 2025Q3

Source: Bloomberg; European Commission

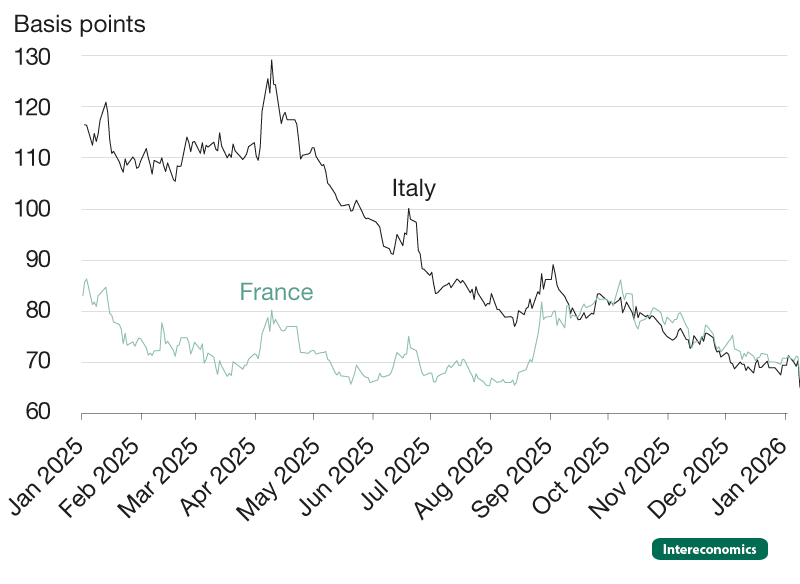

In the meantime, France has moved from AA to A by Fitch and S&P, and has moved (temporarily) away from safe asset status, posting yields close to the highest in the entire euro area (with Lithuania and Malta just above it) (see Figure 2) and trading at levels similar to Italy (BBB rated) (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: ESM and EIB yields held up well in times of market distress

Euro area 10-year yield levels

Source: Bloomberg, 5 January 2026 EOD

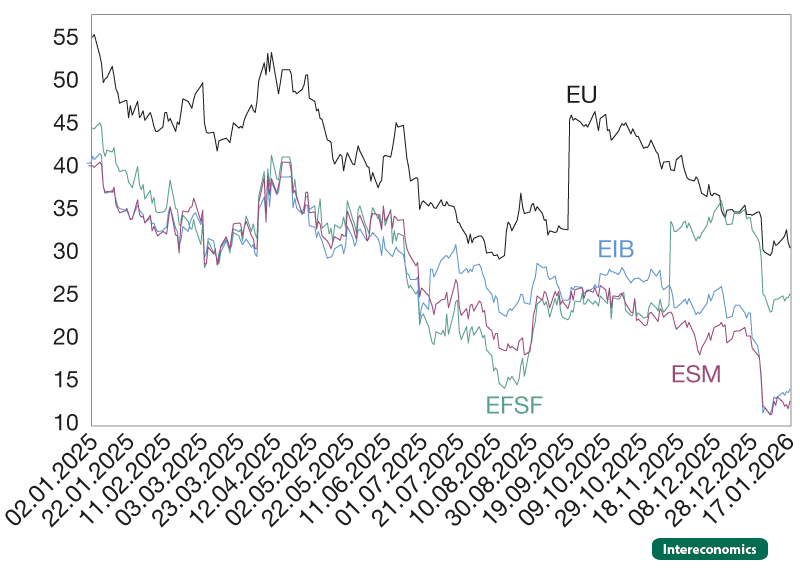

Looking at European safe assets, despite the cycle of market concerns around France and Belgium, and downgrades, the ESM and EIB have kept strong safe asset status. In Figure 2, they trade just above Germany, the Netherlands and Ireland. The EU itself has ten euro area sovereigns trading below it and ten euro area sovereigns trading above it. We can see this also in terms of spread levels in 2025: the EU trades constantly above the other European safe assets (see Figure 4). This can be explained by ESM and EIB having a strong capital structure and being more rating resilient. The EU, and to some extent the EFSF, are more vulnerable to market distress. Despite the EU (and to some extent EFSF) widening a bit more than the EIB and ESM, overall the supranational European safe assets have proven to be resilient to the 2025 market distress related to fiscal concerns in the market and rating downgrades. This should position them even more strongly in the face of future crises when the market for these supranational European safe assets has been developed further.

Figure 4: 10-year European supranational yield spreads vs Germany

Basis points

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Bloomberg data

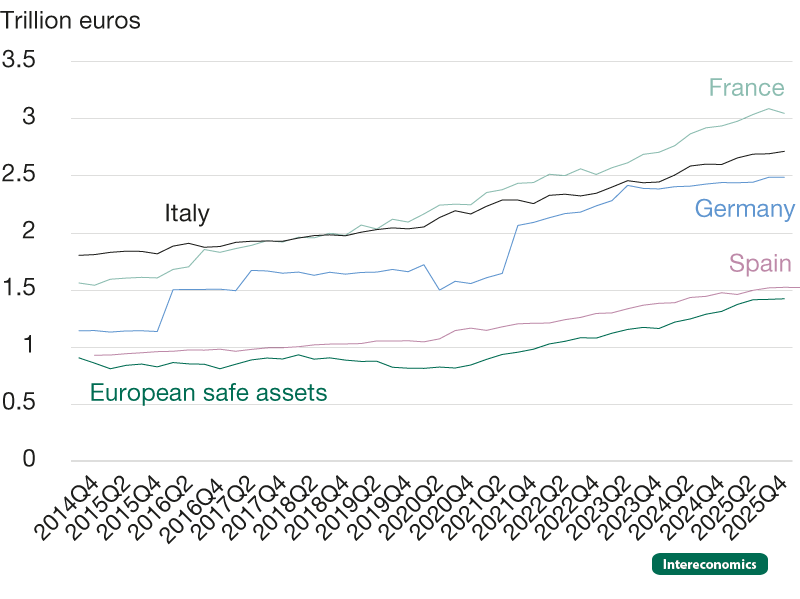

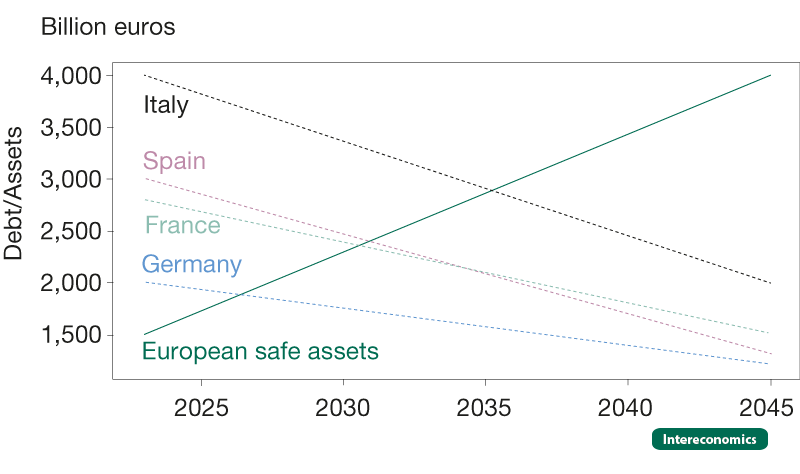

However, while currently outstanding bonds of the EIB, ESM, EFSF and the EU itself may serve as a precursor to a truly safe European asset able to compete with US debt, these bonds largely lack sufficient depth and size. However, the upside is that the momentum around the growth of the supranational European safe assets is increasing. The size of supranational European safe assets has grown over time, reaching almost €1.5 trillion by the end of 2025, making it as large as the “fifth largest country” in the euro area and putting it on the verge of overtaking Spain as the 4th largest country in terms of size and depth of the market (Figure 5).

Further, European borrowing firepower is largely seen as a success. In member countries, European joint debt finance programmes are also more welcomed, as shown by the success of the EU €150 billion Security Action for Europe (SAFE) programme, with 19 countries applying for it, including fiscally conservative countries like Denmark and Finland. Indeed, the political momentum seems to be shifting. Even in the Netherlands, the relatively conservative Christian democratic party CDA made a large shift and opened up to Eurobonds in their party programme for the October 2025 elections: “We are open to taking on joint debt (eurobonds) in emergency situations and for specific investments in European public goods that strengthen our security and open strategic autonomy.” [4] On 29 October 2025, the Dutch elections were won by the progressive and pro-European liberal party D66, which is in favour of a larger European budget, own resources, European taxation and common financing. In their election programme they state:

With a European budget that is twice as large, we can truly face a changing world together. We do this with our own European sources of income. The money goes towards investments that concern everyone, such as defense, green energy, and vital infrastructure like ports. In this way, Europe eases the pressure on national budgets and the European Commission no longer has to go around with a begging bowl (D66, 2025).

Since the conflict in Ukraine, we have seen fiscally conservative countries like Denmark and Finland moving in favour of EPGs and defence financing. Germany’s new government takes a more European stance as well; they were a catalyst for the €800 billion ReArm Europe earlier in 2025 including the SAFE €150 billion joint financing instrument. German Chancellor Merz also called upon a single market securities exchange, in the push for more European capital markets and savings and investment union integration (Chassany, 2025). Hence, we see the political landscape shifting towards more Europe, and the political momentum is building for more European Safe Assets.

The ESM is a further avenue to grow European Safe Assets. At the moment, just €72 billion of its capacity is used. With €86 billion paid in capital and €620 billion callable capital, there is a large potential to use this capacity for further supporting the development of European safe assets. Former European Central Bank board member and chairman of Société Generale Bini-Smaghi (2025) proposed the use of the ESM as an enabler with its €600 billion plus capital to issue Eurobonds in high volumes of highly rated securities.

With the funds raised, the ESM could purchase sovereign bonds from euro area member states at the market price. In the extreme event of a default, the ESM would have to be recapitalised by the country in question, possibly through an ESM loan…. This could be an opportunity to break the deadlock that followed Italy’s veto of the previous reform, and to relaunch a broader discussion on how the ESM can be fully deployed in the service of Europe’s strategic sovereignty. (Bini Smaghi, 2025)

Building on Micossi’s (2021) proposal to leverage the ESM capital, this could bring several trillion euros of European safe assets to the market. According to Micossi, “ESM sovereign purchases could eventually rise to 20-25 % of the euro area GDP, or some EUR 2.5-3 trillion. To do so, the ESM would have to issue a similar amount of its own liabilities, thus leveraging its capital – which is about EUR 705 billion – by a factor between 3.5 to 4.3.”

The EU itself can expand its supply of safe assets by issuing its own debt. There are two main ways to deploy the resulting resources. One is for the mutualisation of national public debt, analogous to the ESM issuing debt to buy sovereign member state debt. This could take place in several different ways. A recent proposal is made by Blanchard and Ubide (2025), who revive the blue-red bond idea, originally put forward by Delpla and von Weizsäcker (2010). Blanchard and Ubide propose that EU member states reserve a certain fraction of their revenues for interest payments on common (blue) senior debt issued by the EU. The proceeds of the EU debt issuance are used to buy a certain fraction of national debts. Hence, part of the national debt that is tradable in a secondary market would be replaced by EU debt, while national interest payments on the national debt in the hands of the EU would be replaced by the interest payments on the EU debt. This would present a possibility to quickly raise the amount of outstanding Eurobonds, making countries jointly responsible for serving this debt. However, the proposal, or any proposal for mutualisation of (part of) the national debts, seems to be a politically difficult sell, because some EU member states fear the risk of a bail-out of countries that would not be able to service their public debts. The question is whether the current political changes, among others the upcoming US stablecoins (currently €300 billion and forecast to grow to €3,000 billion), using US Treasury as collateral, and the absence of a European alternative could open some political doors in this direction.

The other main way is to finance expenditures at the EU level, in particular investments in EPGs of which the benefits extend over a substantial amount of time, justifying the spread of the costs of these investments over multiple cohorts. This should be politically less contentious than issuing EU debt to mutualise sovereign debt, because EU member states would benefit from these EPGs, although there is substantial resistance to EPGs, as discussed above. If this debt is repaid out of the EU budget, it will be redistributive among EU member states to some extent, as the EU budget itself is redistributive. However, one could also envisage that the servicing of this debt is through a specific set of country keys that differs from their net contributions to the EU budget. For example, treating the investments in EPGs as separate projects, the debt-servicing costs could be based on the relative benefits countries enjoy from the EPGs. Such a setup might be the most realistic when EPGs take the form of infrastructure projects in a limited set of member states, as is for example the case for a high-speed railway that connects only a limited set of countries. The EU could issue a common debt title to finance the aggregate costs of all projects, but the contributions to the servicing of the common debt title would depend on the different countries’ stakes in the projects.

As the political will is growing (even in fiscally conservative countries), the financial stability needs of European safe assets are increasing and the push for strategic autonomy is growing, there is momentum to move forward and create deep European financial markets eventually leading to a truly safe European asset. With an increased EU budget, an increase in EIB financing and ESM potential leverage, current European safe assets can grow easily from €1.4 trillion to €4-€6 trillion. It is important to note – for the sceptics – that this will not add to the overall tax burden of European citizens, or the overall level of public indebtedness (see also Boonstra, 2025), ceteris paribus.[5] It will actually reduce it, as financing of public goods on a European level has cost benefits, because these EPGs can provide the same services at a lower cost than public goods provided at the national level. The result would be a pattern as sketched in Figure 6.

Expanding the supply of long-term risk-bearing financing

While an SIU will stimulate EU investments and growth from more savings, the EU can do better still. A larger pool of savings does not automatically mean that good business ideas get the necessary funding. Much of investment is relatively short-term oriented, while good ideas need time to be developed into viable commercial propositions. Banks typically attract short-term capital, which they transform into longer-term loans. However, banks often ask for more security than the developers of new ideas can offer, and the latter may need more time to earn their investments back than bank loans allow for. While in the US, substantial funding is available for new business ideas, often in the form of pools with a portfolio of promising businesses, such funding is scarce in the EU.

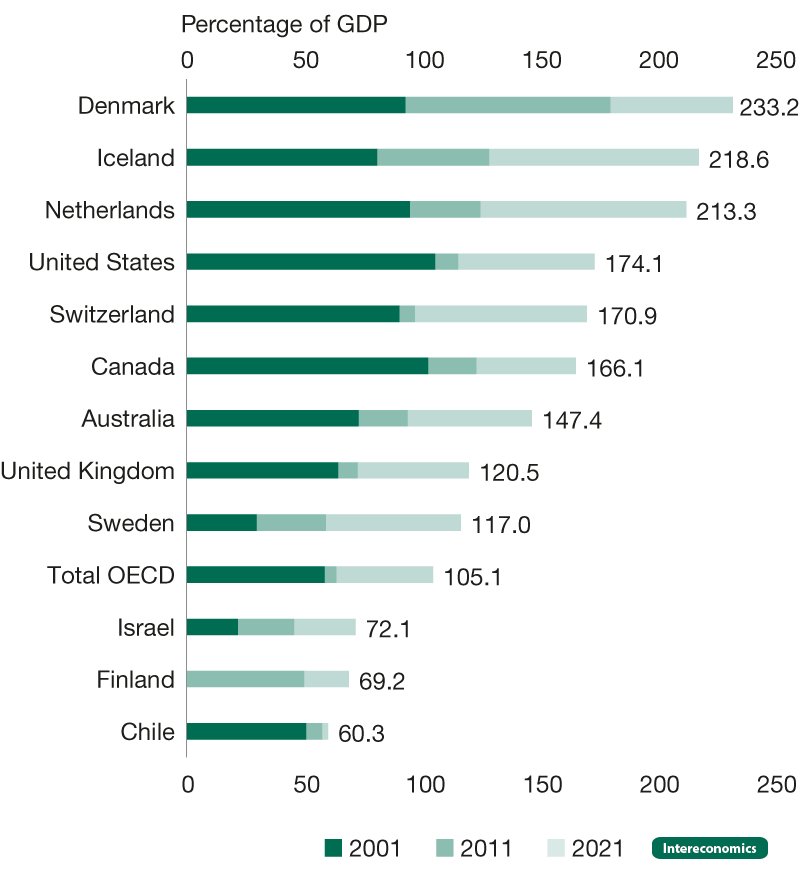

Development of funded pension sectors may provide part of the answer. To keep old-age pension provision affordable, an increase in pension funding will be unavoidable. In the EU, only the Netherlands, Denmark and Finland have substantial amounts of accumulated pension capital (as a fraction of GDP), although assets in funded and private pension plans are growing fast (Figure 7). Other countries rely mainly on pay-as-you-go pension provision. Expansion of pension funding not only helps to deal with population ageing, it also benefits further development of the capital market. Because pension funds have long-term liabilities, they are ideal financial institutions to finance long-term investments. In fact, using Danish administrative data, Beetsma, Jensen et al. (2025) show that the productivity of small and non-listed firms increases following a pension fund equity investment in such firms. This is not to say that taking a stake in any such firm results in a productivity increase. Instead, some large pension funds have specialised teams conducting detailed research leading to the selection of those firms with the most favourable growth prospects. Pension fund investment in such firms provides a long-term financing commitment, raises their overall supply of financing directly – as well as indirectly by giving a positive signal to the rest of the market. However, the selection of promising companies is costly for large pension funds, as the selection process is labour-intensive and the stakes in those companies are small compared to the size of the funds (Beetsma et al., 2024). Setting up investment pools by pension funds, and possibly other institutional investors, could be a good way to spread those costs and achieve scale in funding promising companies.

Concluding remarks

In this contribution we have argued that the EU economy needs a combination of measures that strengthen each other. These are European public goods, an enlarged EU budget, more own resources, and a truly European safe asset that finances these public goods and underpins a well-functioning savings and investment union.

It is the combination of these measures that is essential: some public goods have EU-wide benefits, hence need to be financed through an enlarged EU budget with a shift in priorities away from the current ones. It is intergenerationally fair to finance these goods through the issuance of Eurobonds. To ensure a deep and liquid market in which they are traded at the lowest possible yields requires an EU budget underpinned by a sufficient fraction of own resources. Own resources are set to gradually, but slowly, expand, and the political appetite for a big push in this direction seems low. However, the momentum for an expansion of the volume of European safe assets seems to be increasing, which provides an opportunity to push forward on this dimension. Working around the resistance to European public goods might require the formation of coalitions of those countries willing to invest in these goods for their own group. EU co-financing could help to stimulate these investments.

The total volume of investment funding extends far beyond public funding at the European level. Most of this funding needs to come from the private sector. Making this possible requires a well-functioning savings and investment union underpinned by a truly European safe asset, in combination with sufficient supply of long-term risk-bearing capital. The latter can be promoted by expanding pension funding, which would in any case be needed to finance population ageing, but which also expands the supply of capital available for long-term investments in new technology and infrastructure.

References

Anev Janse, K. (2023). Developing European Safe Assets. Intereconomics, 58(6), 315–319

Anev Janse, K., Beetsma, R., Buti, M., Regling, K., & Thygesen, N. (2025, January 15). European public goods: the time for action is now. Bruegel Analysis

Beetsma, R., Betermier, S., van Dam, J., Hougaard Jensen, S. E., Lanters, F., Lyon, M., Lyngsø Madsen, A., Neft, M., Pattiwael, F., Reeve, A., Roy, A., Scott, W., & Simutin, M. (2024). The Four Ways Through Which Pension Funds Increase the Productivity of Firms They Invest In. International Centre for Pension Management.

Beetsma, R., & Buti, M. (2024). Promoting European Public Goods. CESifo EconPol Forum, 25(3), 37–41

Beetsma, R., Buti, M., & Nicoli, F. (2025). EU Defense Union: Short-Term Feasibility and Long-Term Coherence. CESifo EconPol Forum, 26(3), 22–28

Beetsma, R., Jensen, S. E. H., Pinkus, D., & Pozzoli, D. (2025). Equity Financing and Economic Growth: Does Pension Fund Equity Investment Boost Firm Productivity? Mimeo. Copenhagen Business School and University of Amsterdam

Bini-Smaghi, L. (2025). The Purpose of Eurobonds. Institute for European Policy Making Bocconi University

Blanchard, O., & Ubide, A. (2025). Now is the time for Eurobonds: A specific proposal, Realtime Economics. Peterson Institute for International Economics

Boonstra, W. W. (2025). Eurobonds zijn nodig voor kapitaalmarktunie en leiden niet per se tot extra schulden. Economisch Statistische Berichten, to appear

Chassany, A.-S. (2025). German chancellor Friedrich Merz calls for single European stock exchange. Financial Times

Claeys, G., & Steinbach, A. (2024). A conceptual framework for the identification and governance of European public goods. Bruegel Working Paper

D66. (2025). Het kan wél: Verkiezingsprogramma 2025–2030 (It can be done: Election programme 2025–2030)

Delpla, J., & von Weizsäcker, J. (2010, May 6). The blue bond proposal. Bruegel Policy Brief

Draghi, M. (2024). The Future of European CompetitivenessThe Future of European Competitiveness

Draghi, M. (2025). High Level Conference – One year after the Draghi report: what has been achieved, what has changed

ELEC. (2024). Why EU Capital Markets Union has become a “must have” and how to get there [Position Paper]

European Commission. (2020). Stepping up Europe’s 2030 climate ambition – Investing in a climate neutral future for the benefit of our people. Commission Staff Working Document, (2020) 176 final

European Commission. (2021, November 25). State aid: Commission adopts revised State aid rules on Important Projects of Common European Interest [Press release]

European Commission. (2025). The 2028-2034 EU budget for a stronger Europe.

Fuest, C., & Pisani-Ferry, J. (2019). A Primer on Developing European Public Goods. EconPol Policy Report, 16. European Network for Economic and Fiscal Policy Research

Letta, E. (2024). Much more than a market: speed, security, solidarity. Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU Citizens

Marcus, J., &. Thomadakis, A. (2025, June 5). Identification of hurdles that companies, especially innovative start-ups, face in the EU justifying the need for a 28th regime. Presentation at the Workshop “The 28th Regime: a new legal framework for innovative companies”.

Micossi, S. (2021). On the selling of sovereigns held by the ESCB to the ESMs. Policy Brief, 17/2021. Luiss School of European Political Economy

Pisani-Ferry, J., Tagliapietra, S., & Zachmann, G. (2023). A new governance framework to safeguard the European Green Deal. Policy Brief, Issue No. 18/23. Bruegel

Villeroy-de-Galhau, F. (2025). The international role of the euro and the development of European safe assets. Speech at the European Stability Mechanism

Von der Leyen, U. (2025). Opening keynote speech by President von der Leyen at the ‘One Year After the Draghi Report’ Conference.

Weber, M., García Pérez, I., Hayer, V., Reintke, T., Eickhout, B., Mureșan, S., Tavares, C., Keller, F., & Nordqvist, R. (2025, October 30). The European Parliament rejects the National and Regional Partnership Plans proposal as it stands and demands an amended proposal to start negotiations. Letter to the President of the European Commission

Wyplosz, C. (2024). Which European Public Goods? In-depth Analysis requested by the ECON Committee. European Parliament

Footnotes

* Views are personal and may not reflect the views of the institution and its shareholders.

Author

Contacts