Capital markets in the Baltic region: a deep dive

ESM Briefs is a concise presentation of research by ESM staff members, helping readers better understand and navigate current economic policy debates. More about ESM Briefs

Abstract

This ESM Brief follows up on the recent ESM Discussion Paper Capital Markets Union Redux: towards a deeper and more equitable Savings and Investment Union. In that paper, a comparative approach was applied, aiming to identify best-practice examples from EU countries, focusing on measures to broaden retail participation in capital markets and enhance cross-border investments. Many of these examples come from the Netherlands or the Nordic countries, which have the most developed capital markets in Europe. Making progress on these areas of the European Commission’s agenda for a Savings and Investments Union (2025) brings particular benefits for the Baltic countries, given that their capital markets are less developed than other Member States. Moreover, the innovative nature of the Baltic financial sector, along with the outspoken ambition of local policymakers to foster capital markets development are factors that may enable the region to make faster progress on related policy initiatives. Advancing a joint Baltic capital market beyond the general steps taken at the European level carries additional benefits, particularly in policy areas which fall under national competence. Here, initiatives that foster closer regional market integration can generate the scale and depth which individual Baltic countries are lacking.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Arndt Gerrit-Kund for help with supporting analysis, Bernhard Mayr, Nicoletta Mascher and Rolf Strauch for the valuable discussions and comments to this blog post, and Karol Siskind for the editorial review.

INTRODUCTION

The total population of the three Baltic countries is just over 6 million people. While the individual economies are small, their combined GDP – which stood at around €160 billion in nominal terms in 2024 – is comparable in size to that of Slovakia (€130 billion) or Hungary (€206 billion).[1] The financial sector is characterised by a large presence of subsidiaries of Nordic banks, with an efficient, highly digitalised operating model. More recently, the region has played host to innovative fintech ventures, like Revolut, who have successfully managed to grow their franchise to cover a pan-European footprint. On the policy front, a number of initiatives have been launched that aim to create a single, pan-Baltic capital market envisioned as a building block of the European Union’s Capital Markets Union initiative.[2] These include a harmonised covered bonds regime,[3] as well as the 2023 launch of the MSCI Baltic Index, a new single index aiming to enhance the visibility of Baltic companies to international investors and foster a more unified Baltic equity market.[4] In line with the latter initiative, shares of firms in each of the three countries are listed jointly on the Nasdaq Baltic stock exchange, facilitating cross-border investments. Both initiatives have been supported by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

In the first section of this ESM Brief, we provide a profile of household savings in the Baltic countries, followed by a section with policy considerations tailored to the specificities of the local markets. In line with the scope for the ESM discussion paper, the chosen focus for these policy considerations is on measures to broaden retail participation and expand cross-border investments. As such, we do not consider e.g. initiatives related to financial infrastructure or post-trade settlement.

PROFILE OF HOUSEHOLD SAVINGS IN THE BALTIC COUNTRIES

Baltic households are less wealthy and save less than European peers...

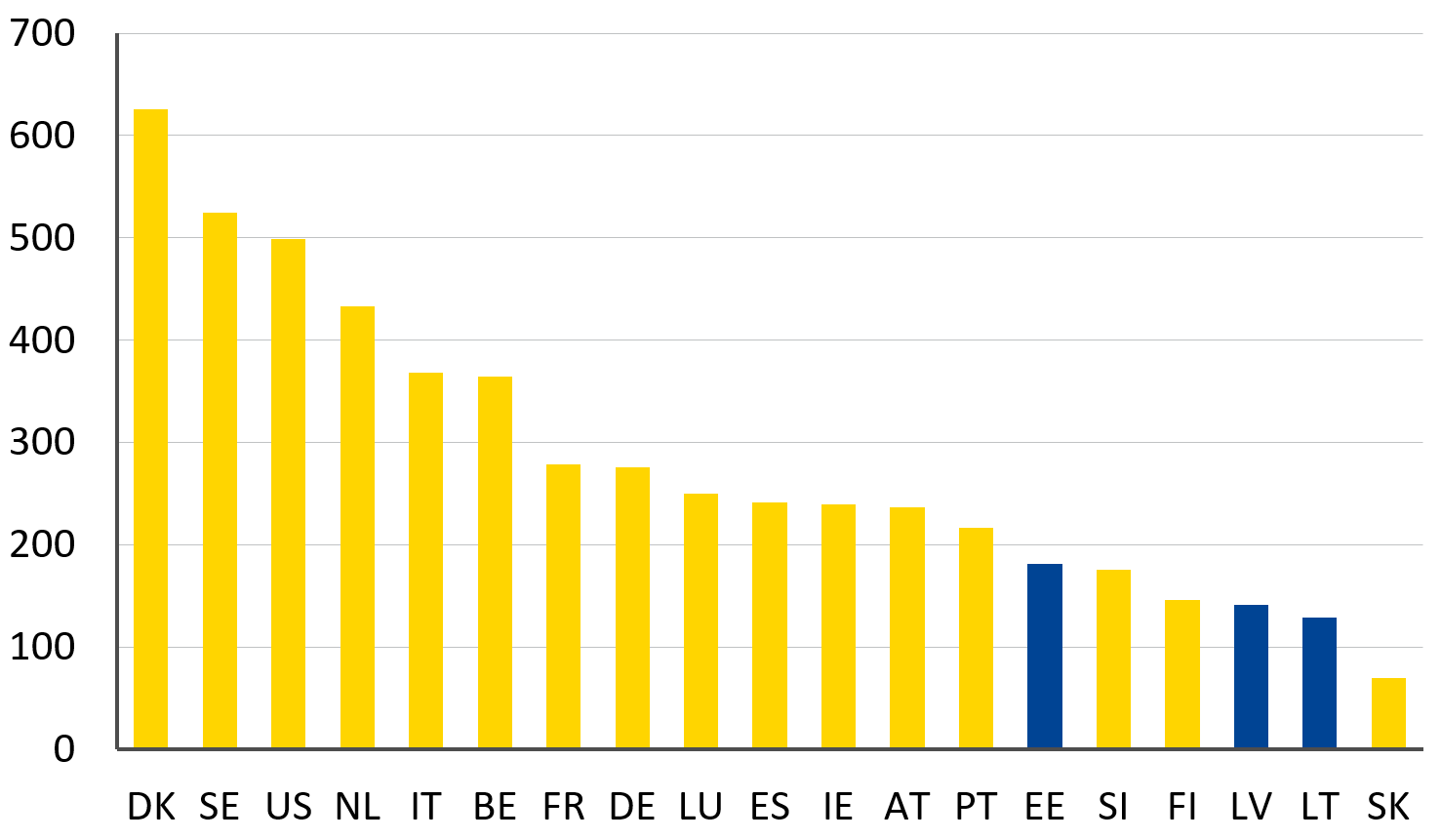

Most European countries have substantial pools of savings available for investments, as shown by a relatively high ratio of household financial wealth to disposable income (Figure 1), but there is substantial variation across countries and the Baltics are at the lower end of this range. Similarly, while European saving rates are relatively high as a proportion of income, the saving rate in the Baltic countries is significantly below the EU and euro area averages.

Figure 1

a) Household net financial worth

(in % of disposable income)

b) Gross household saving rate

(in % of disposable income 2012–2023)

Note: Households’ net wealth includes (i) deposits, (ii) insurance and private pension products, (iii) loans granted by the household sector, (iv) shares, (v) other accounts receivable, and (vi) gold.

Sources: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Q4 2022; and Eurostat

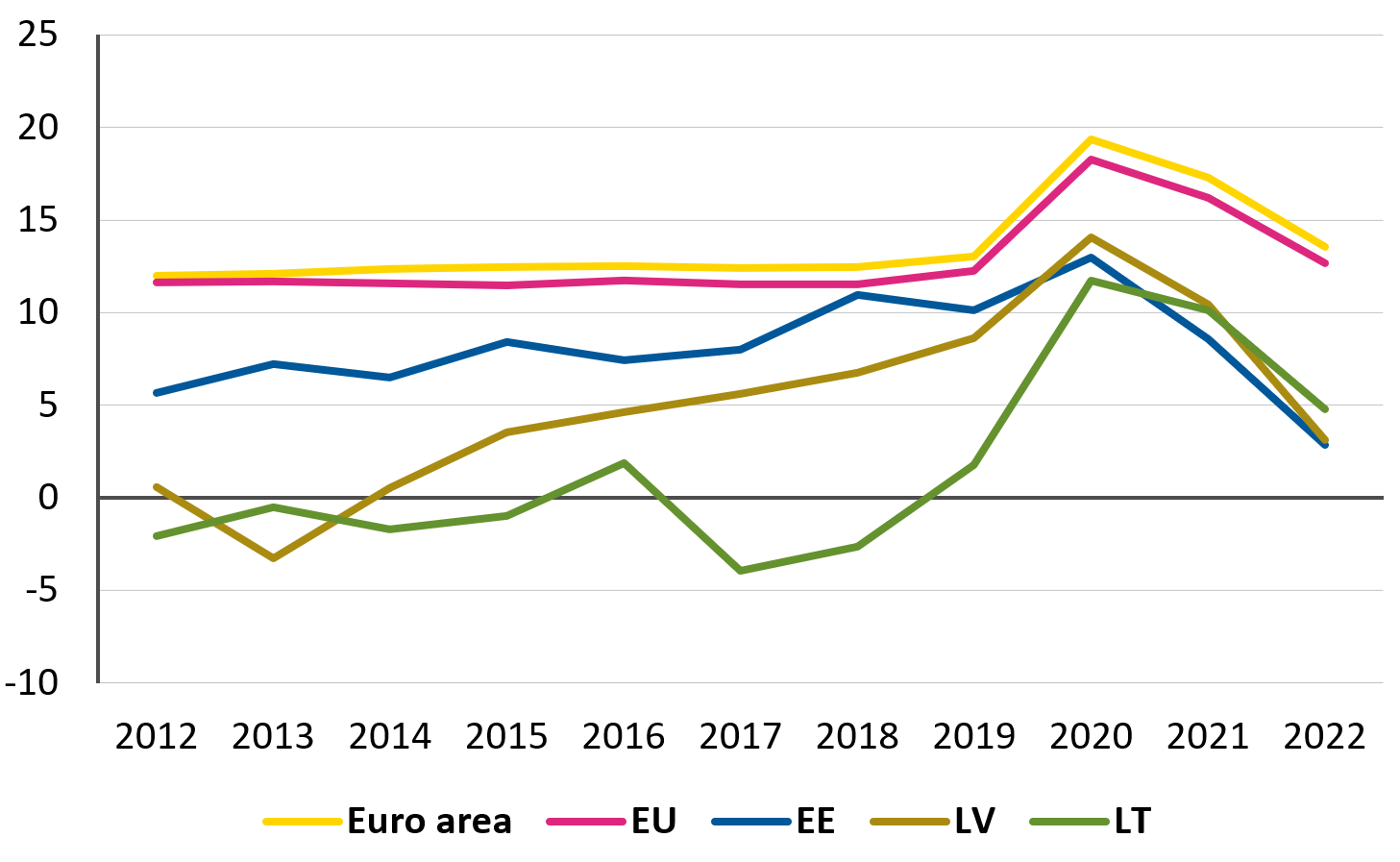

Turning to the allocation of their savings, there is substantial variation across the Baltic countries, with Estonian households allocating the largest share of savings (72%) to equity and investment fund shares of all European countries[5] and a relatively low share to deposits. Latvian and Lithuanian households meanwhile allocate a share of their savings to deposits that is similar to, if slightly higher than, the euro area average.

Figure 2

Households’ distribution of financial assets

(in %, Q4 2023)

Source: ESA 2010 Statistics and Haver Analytics

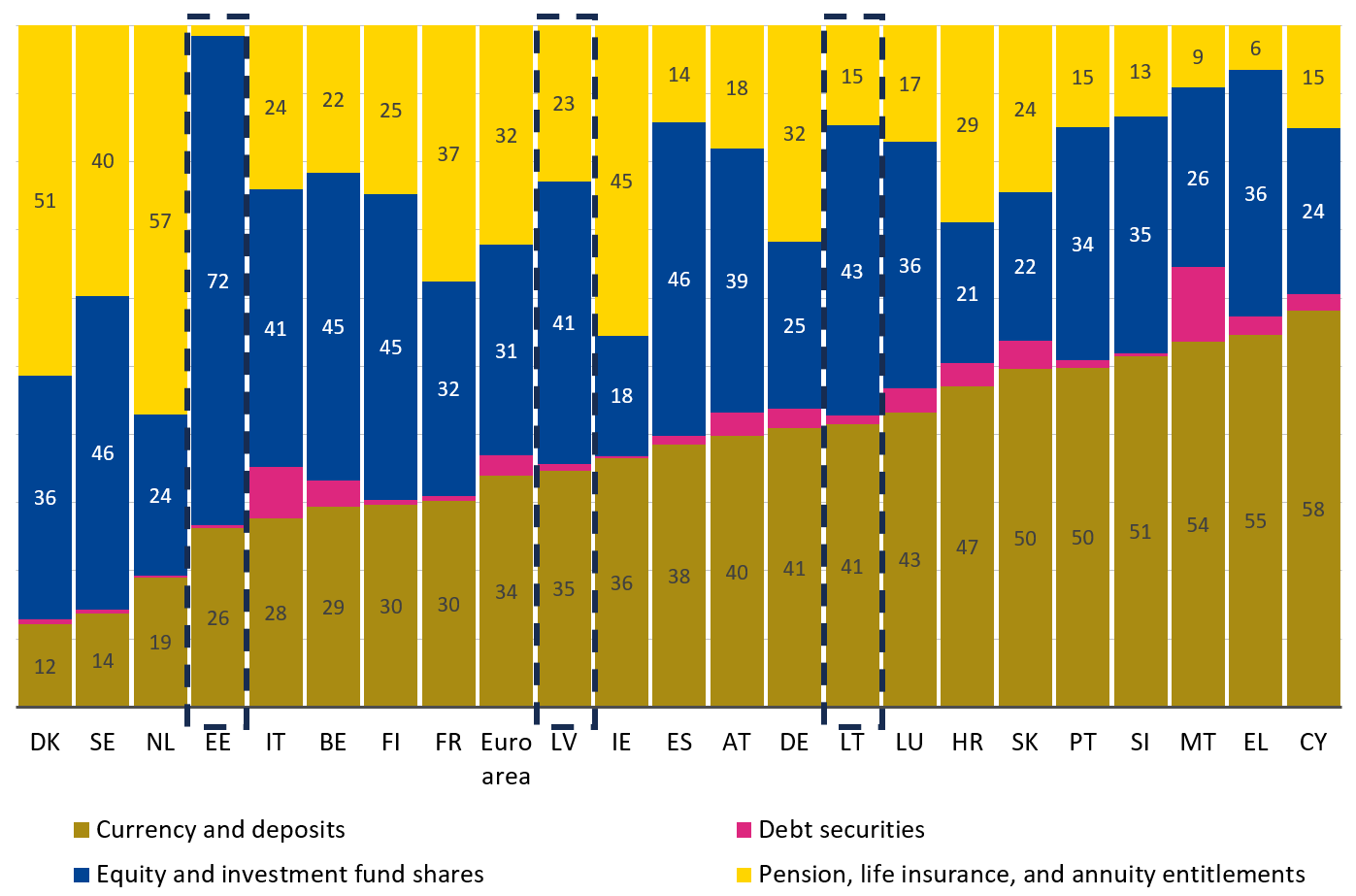

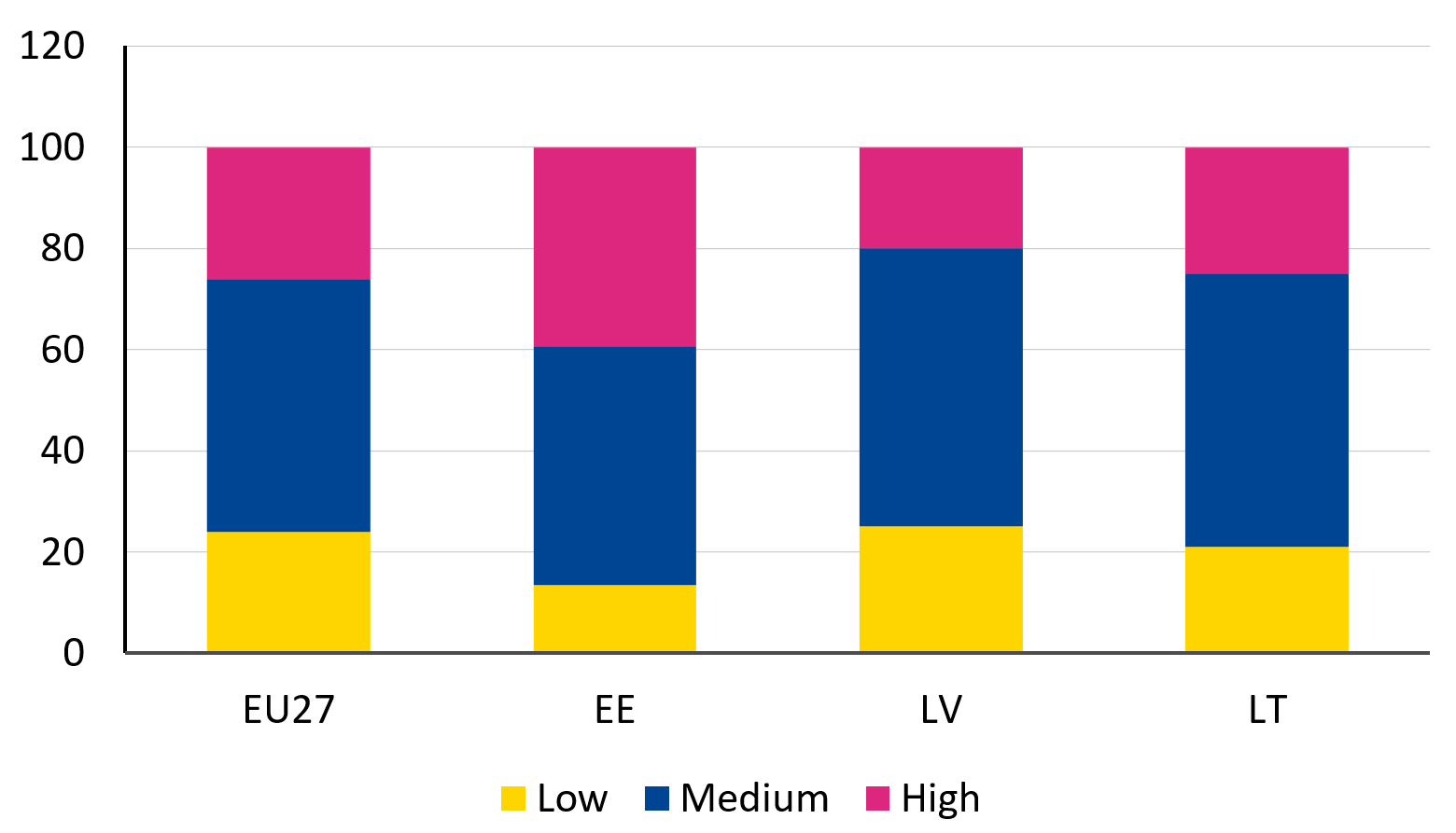

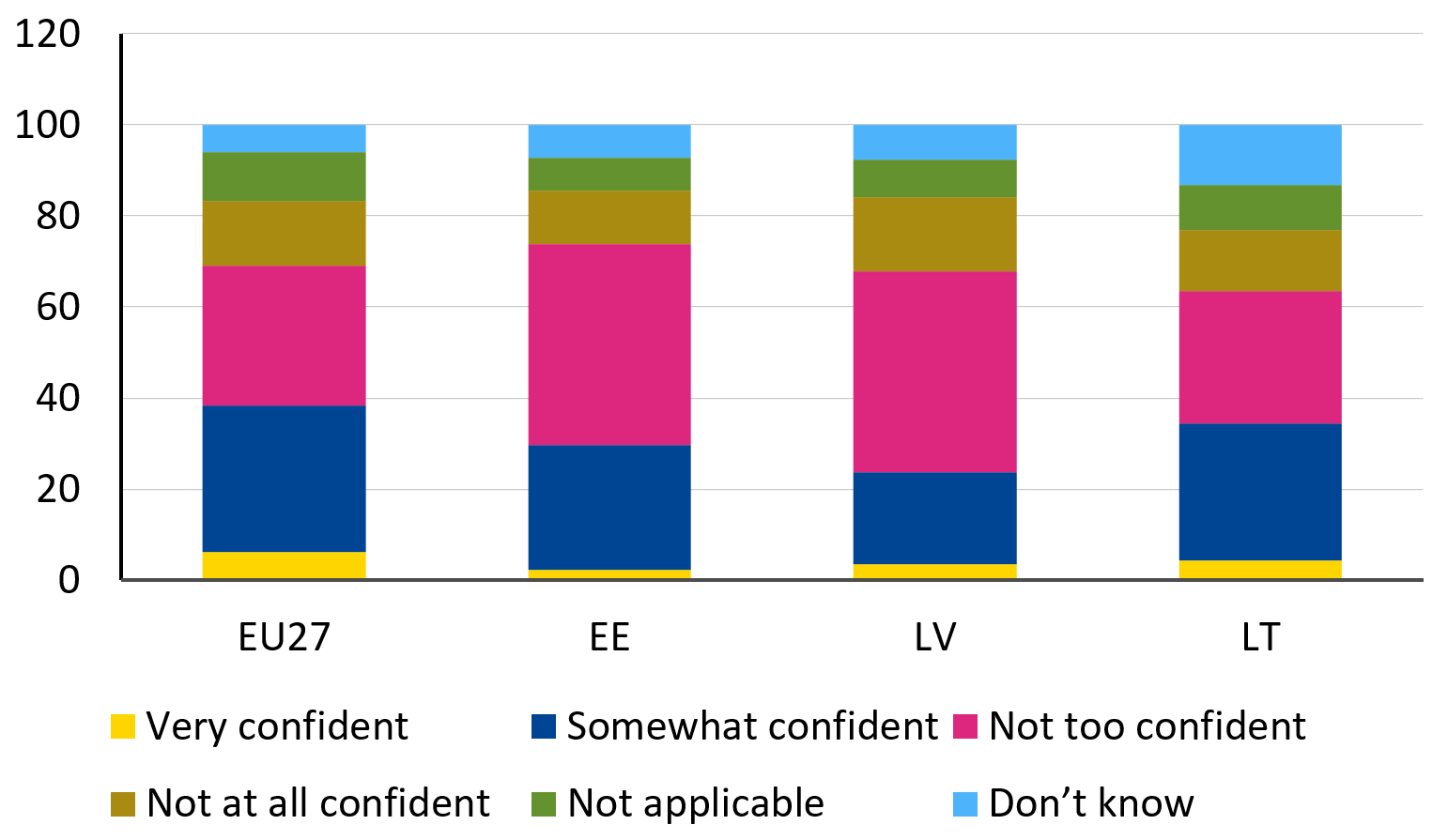

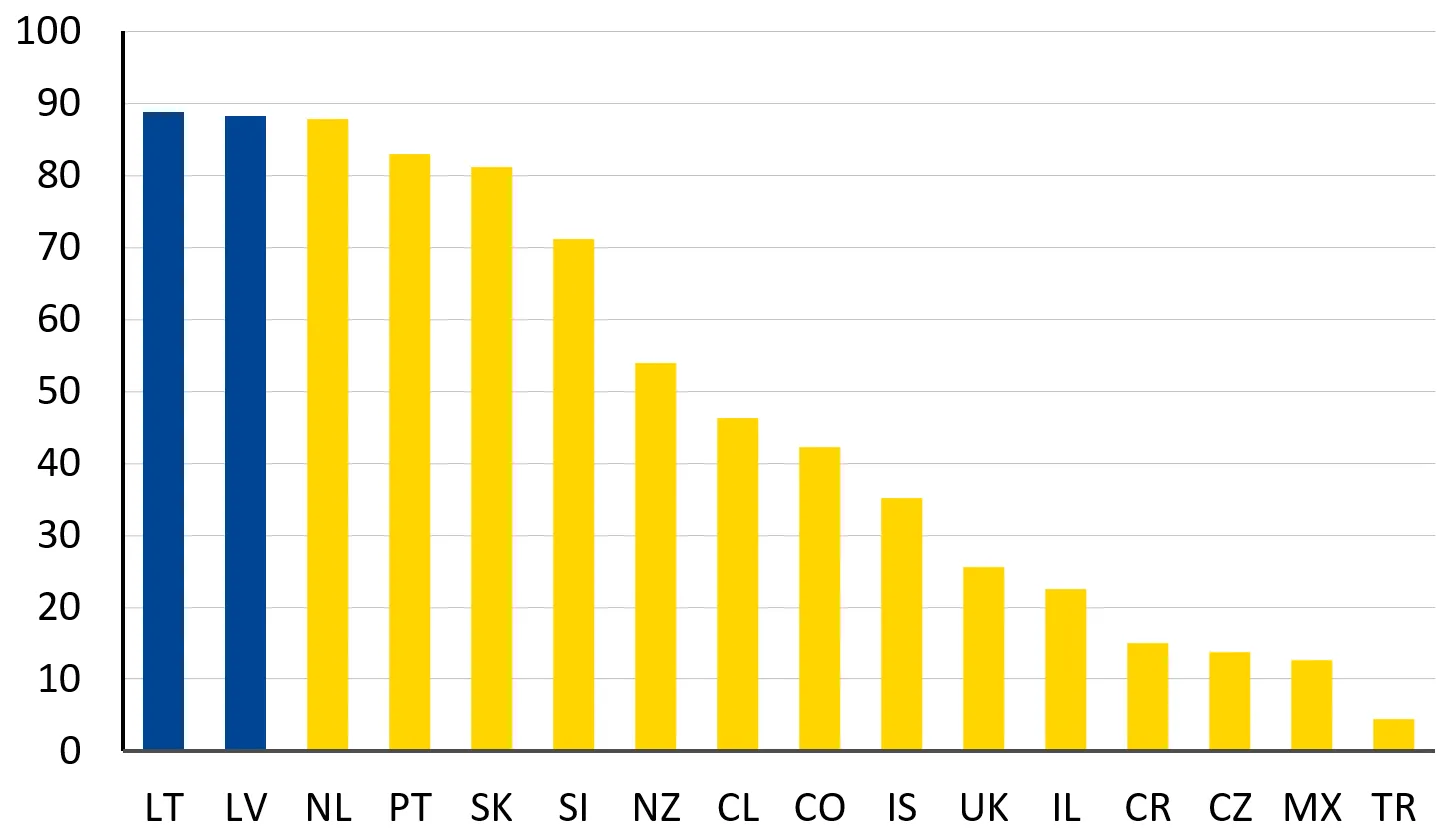

This, in turn, reflects a sound level of financial literacy among the general population, with Estonia scoring significantly higher than the EU 27 average in the 2023 EU Barometer survey, Lithuania somewhat higher and Latvia just below (Figure 3a).[6] However, trust in investment advice received from banks and financial advisors is relatively low (Figure 3b).[7]

Figure 3

a) Financial literacy score

(in %, 2023-Q3)

b) Trust in investment advice

(in %, 2023-Q3)

Source: Eurobarometer on Monitoring the level of financial literacy in the EU, 2023

...but have relatively ample retirement savings..

One of the key policy recommendations in the aforementioned ESM Discussion Paper relates to the role of funded pensions in supporting capital markets development. Case studies from the Netherlands and Sweden illustrate the role that pension funds can play in providing long-term capital for early-stage equity investment, driving new firm creation, employment and productivity growth. Looking at the scale of assets earmarked for retirement as a percentage of GDP (Figure 4), the Baltic countries actually compare favourably to European peers, with Estonia and Latvia both ahead of Spain, Italy and France, although some way behind leading countries.

Figure 4

Assets earmarked for retirement

(in % of GDP)

Source: OECD, at end-2022 or latest available

The relatively ample retirement savings reflect the fact that all three Baltic countries undertook important pension system reforms in the 1990s, seeking to increase the role of funded pension schemes (see Box below for an account of these reforms). In shifting the burden to rely more on funded schemes, these reforms have also served to lower the replacement rate of state pay-as-you-go (PAYG) pension schemes (Figure 5), although less so in Latvia than in Estonia and Lithuania. As such, the Baltic countries are in a favourable position compared to many European peers, in having already implemented reforms that help to reduce the cost of ageing populations.

Box 1. Pension system reforms in the Baltic region

Shortly after gaining independence, all Baltic countries pursued important pension system reforms. These were largely based on the analysis and recommendations of the World Bank report Averting the Old Age Crisis: Policies to protect the old and promote growth published in 1994. The authors recommended that sufficient incomes in retirement should be ensured for the elderly through a combination of a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) system and funded pensions paid from savings built up during years of work. Below is a brief overview of the second (funded) pillar of the pension system in each country. A feature common to all three countries is that the pension schemes are funded through social security levies charged to employers and collected by state tax authorities. As such, they contrast with how second pillar schemes are typically managed in other countries, by not being occupational pension schemes in a strict sense.

Estonia

The Estonian pension system underwent a fundamental reform starting in the late 1990s. Voluntary supplementary pensions were introduced in 1998, the first pillar was modernised in 1999/2000 and the mandatory second pillar was implemented in 2002. The pension plans in the second pillar are defined contribution (DC) schemes, with mandatory participation for employees born in 1983 or later. Participants contribute 2% of their gross salary while employers contribute an additional 4% through social security levies collected by the state. Individual pension accounts are managed by private pension fund managing companies (typically subsidiaries of a bank), who provide a choice between three types of funds: conservative funds with a 100% allocation to bond and money market instrument, balanced funds with up to 25% of equities and at least 50% bonds and money market instrument and progressive funds with an equities limit of up to 50% and no limit on bond and money market instruments. A fourth option with a higher allocation to equities was introduced in 2010. Following a reform in 2021, participation is no longer mandatory and citizens are free to make an early withdrawal from their pension funds.[8]

Latvia

Like Estonia, Latvia initiated a review of its pension system shortly after independence in 1991. Today, the first pillar is a PAYG, notional defined contribution (NDC) system[9] while the second is a funded DC pillar that was made mandatory for new labour market entrants and employees aged below 30 at the time of its introduction.[10] Contributions to the second pillar have been raised consecutively from around 4% in 2007 to 10% in 2010. During the financial crisis, contributions were lowered to 2% but have gradually been raised again. Like in Estonia, individual pension accounts are managed by private companies, although initially they were managed by the State Treasury. While the State Treasury was only allowed to invest in Latvian government securities, bank deposits and mortgage bonds, accounts managed by private companies can offer a choice of 3 funds: conservative funds with a 100% share of bond and money market instrument, balanced funds with up to 15% of equities and at least 50% bonds and money market instrument and progressive funds with an equities limit of up to 30% and no limit on bond and money market instruments. These limits entail a fairly conservative asset allocation for Latvian retirement savings, offering low investment returns during the period of low interest rates.

Lithuania

Like its Baltic neighbours, Lithuania undertook major pension system reforms shortly after independence. The second pillar of funded DC pensions was introduced in 2004. Unlike Estonia and Latvia, participation was made voluntary through an auto-enrolment scheme with an opt-out clause, although irreversible once an employe has decided to join. From 1 January 2019, participants contribute 3% from their gross salary, with a 1.5% contribution from the state calculated based on the country’s average wage. Like in Estonia and Latvia, individual pension accounts are managed by private companies. These companies must provide at least one fund with a conservative asset allocation (i.e. 100% in government securities), but are otherwise free to offer funds with a riskier portfolio composition. A major reform of the second pillar was undertaken in 2019, which introduced a lifecycle investment strategy as the default choice and put a cap on annual management fees of 0.5%.[11] Following a political decision earlier this year, participants can now opt to suspend contributions and/or make a one-time withdrawal of 25% of their accumulated funds.[12]

Figure 5

Replacement rates of PAYG pension schemes

(percent)

Source: EC report on ageing and pensions

..yet pension funds have not contributed as much to capital markets development

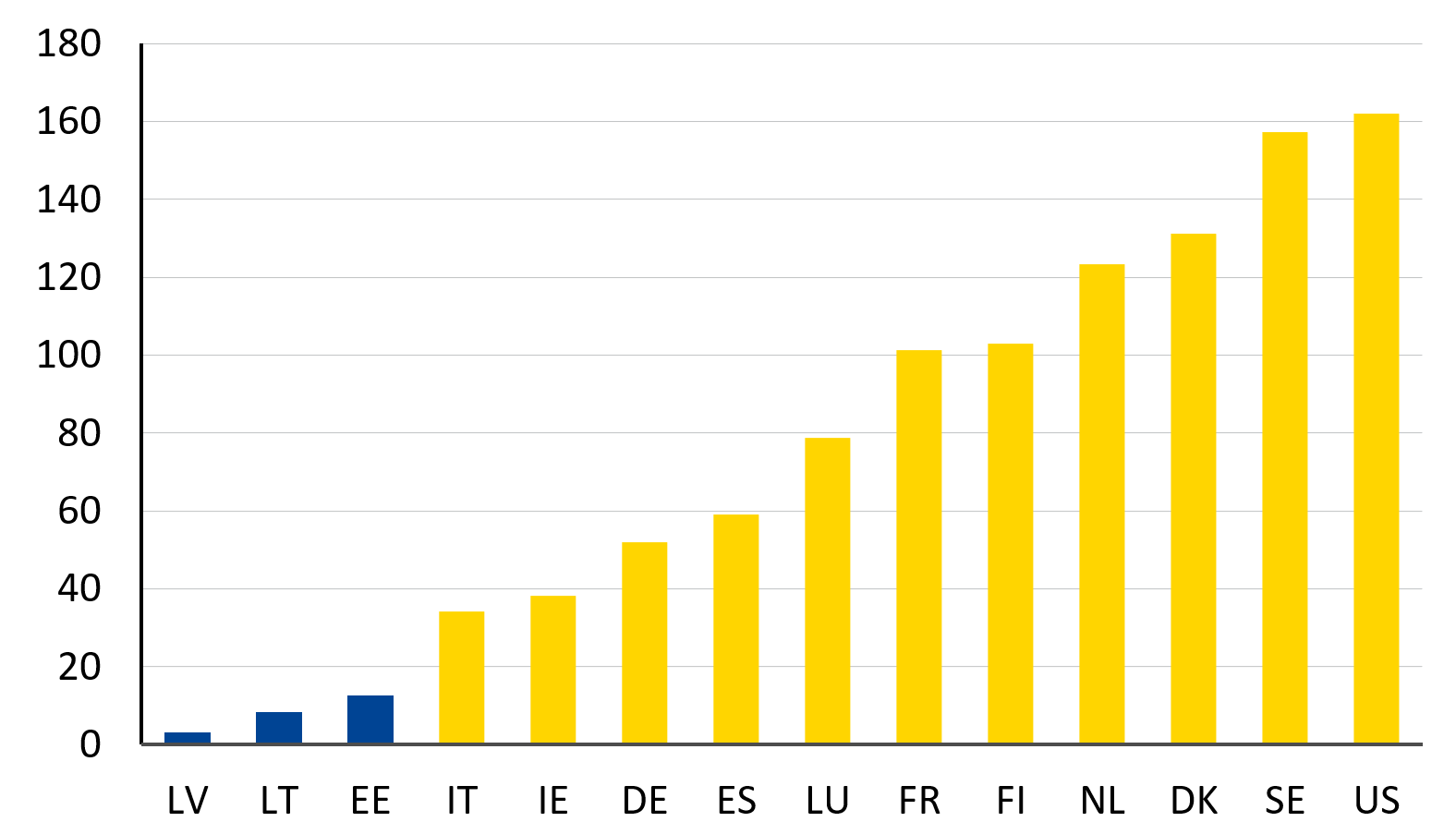

One might expect the relatively ample supply of pension savings to translate into favourable conditions for local stock markets. However, when turning to stock market capitalisation as a percentage of GDP, the Baltic countries stand out as having the lowest relative market capitalisation in the sample (Figure 6). This stands in strong contrast to the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden, where funded pension systems back high market capitalisation.

Figure 6

Stock market capitalisation

(in % of GDP, average 2014–2022)

Source: World Bank, CEIC, and ESM Staff calculations

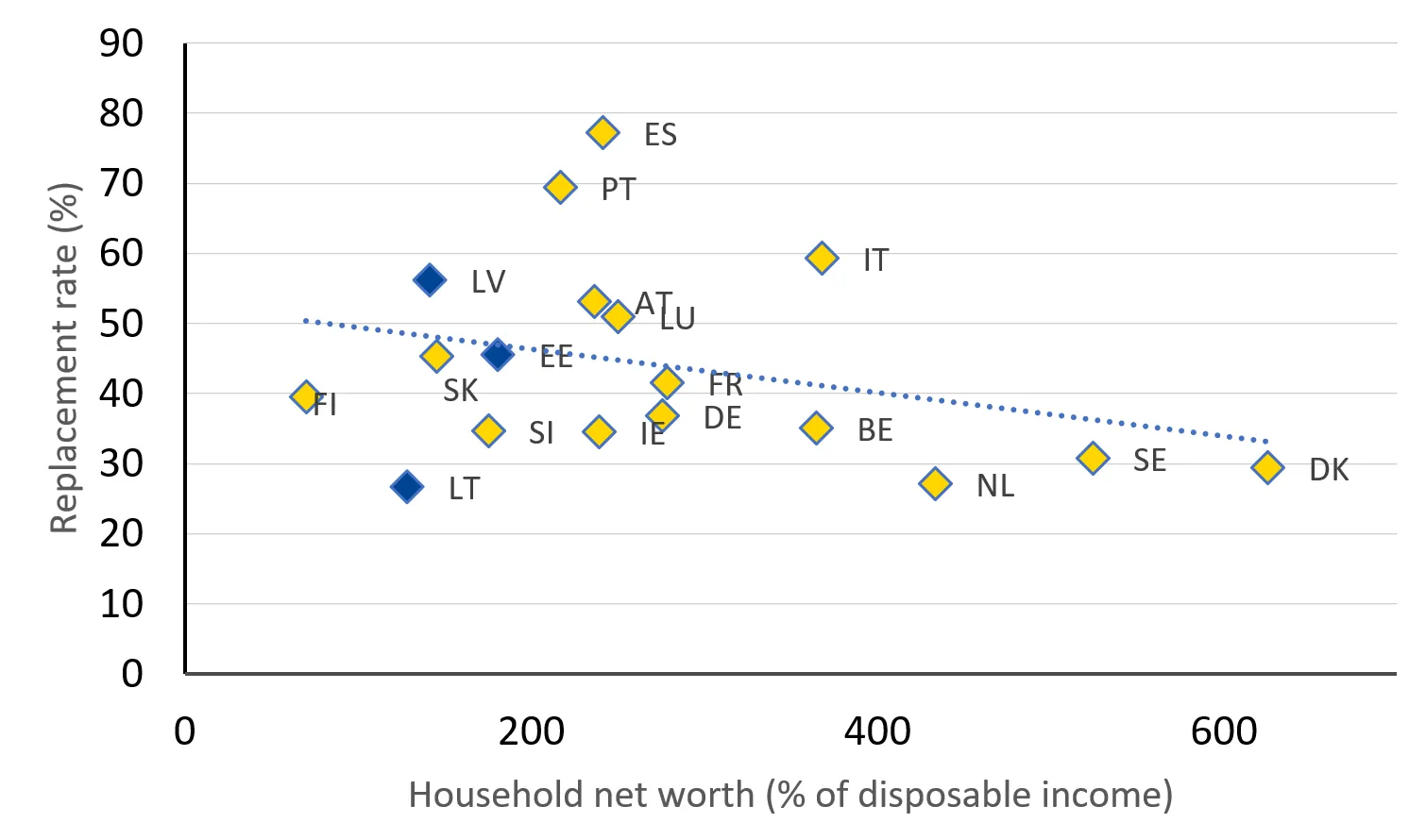

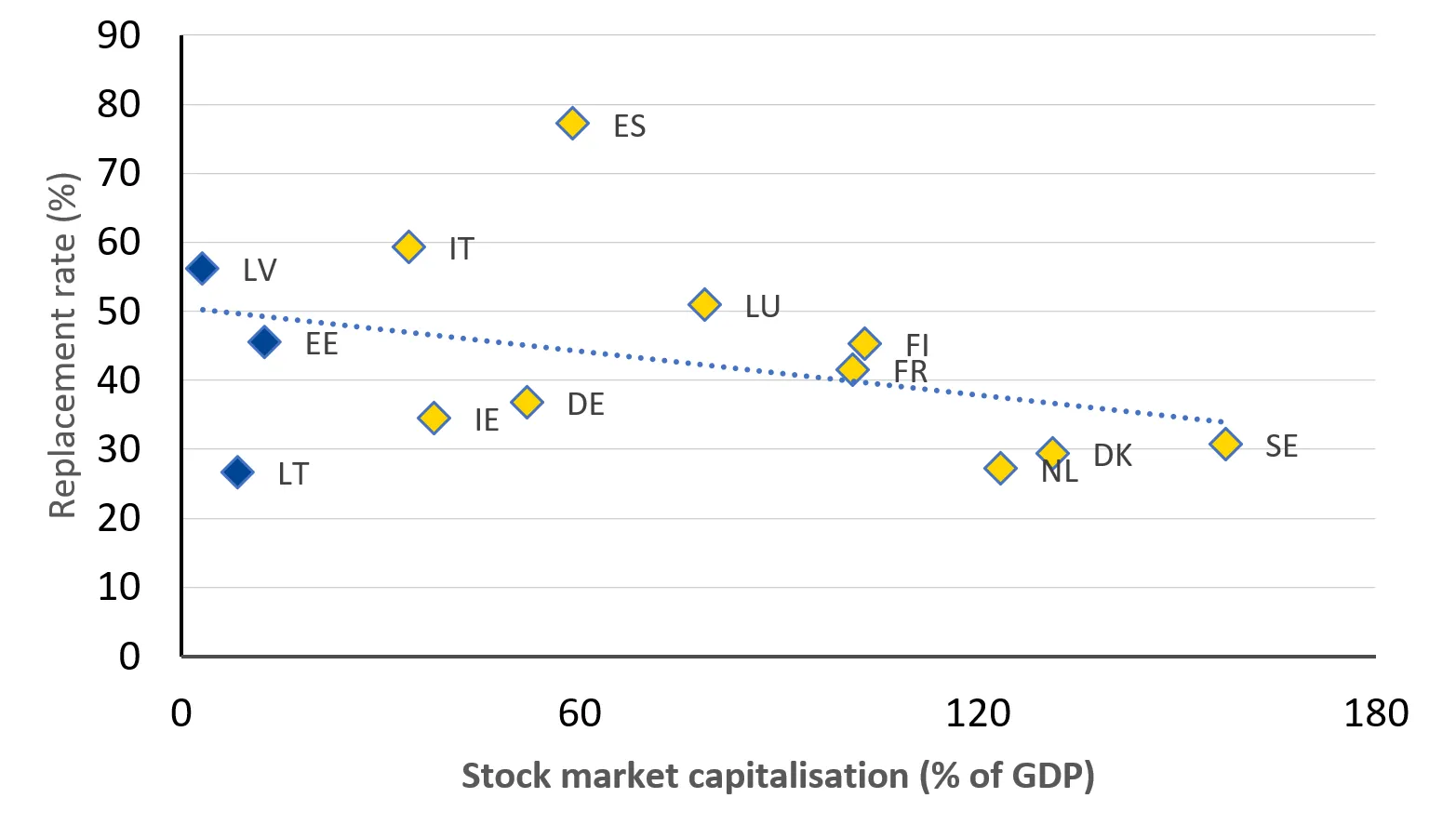

The general pattern that European countries with lower replacement rates have higher household wealth and stock market capitalisation, as citizens are then incentivised to save more and invest for their future retirement, evidently does not hold as well for the Baltic countries (Figure 7). Lithuania has the lowest replacement rate of PAYG pensions, but household wealth is lower than in both Estonia and Latvia and while its stock market capitalisation is slightly higher than Latvia’s, it lags behind Estonia’s. This suggests that the pension system reforms in the Baltics have failed to generate financial household wealth to the same degree as in peer countries but also contributed less to stock market development.

Figure 7

a) Household net worth (% of disposable income) and replacement rates (in %)

Note: Data on household net worth are as per Q4 2021, while replacement rates are for 2022.

Source: OECD, EC report on ageing and pensions

b) Stock market capitalisation (% of GDP) and replacement rates (in %)

Note: Stock market capitalisation to GDP is averaged over 2014-2022, while replacement rates are for 2022.

Source: World Bank, CEIC, EC report on ageing and pensions

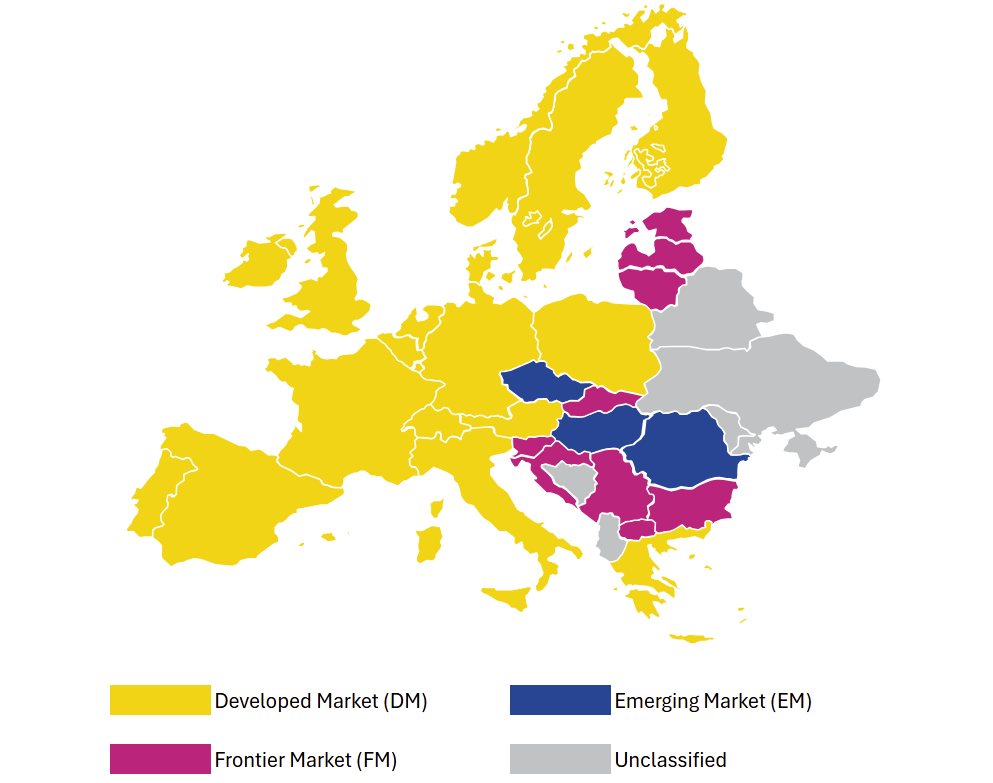

Based on reports from international organisations and discussions with local stakeholders, among the reasons for their limited contribution to household wealth are the high fees charged by the pension funds (Figure 12a), as well as poor investment returns, partly driven by conservative asset allocations with a low share of assets in equities and a larger share in low-yielding safe assets. In addition, Latvian and Lithuanian funds invest a high share of their portfolio in foreign assets (Figure 12b). For pension funds operating in a small economy, this arguably reflects prudent principles of investment management, driven by the low weight of their domestic capital markets in a global portfolio, as well as lower liquidity of the assets. The limited scale and liquidity of Baltic stock markets is reflected in their being categorised by both MSCI and FTSE (major providers of stock market indices) as Frontier Markets, which typically limits the amount that institutional investors can allocate to invest in them. The only other EU member states classified as Frontier Markets by MSCI are Croatia and Romania, while FTSE also include Cyprus, Malta, Slovakia and Slovenia (Figure 8).

..which are held back by their Frontier Market classification

Figure 8

Classification of stock markets

Note: Classification of stock markets in accordance with FTSE methodology. Cyprus and Malta are also classified as frontier markets, but not shown in this visualisation.

Source: FTSE

The limited scale and liquidity of Baltic capital markets, reflected in their Frontier classification, creates a form of deadlock whereby institutional investors are deterred from investing in them, which in turn prevents them from growing and reaching more scale. Initiatives that seek to pool the regional investor base thus make sense to gradually increase market depth and liquidity, and the conditions for doing so are favourable.

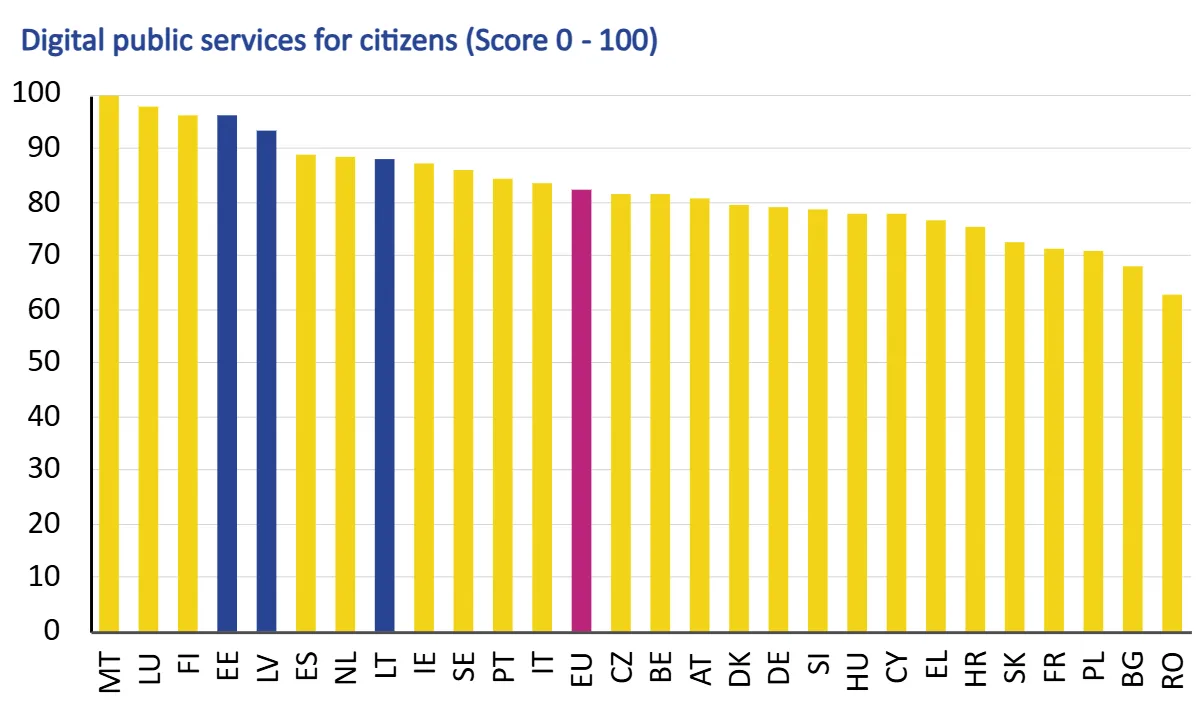

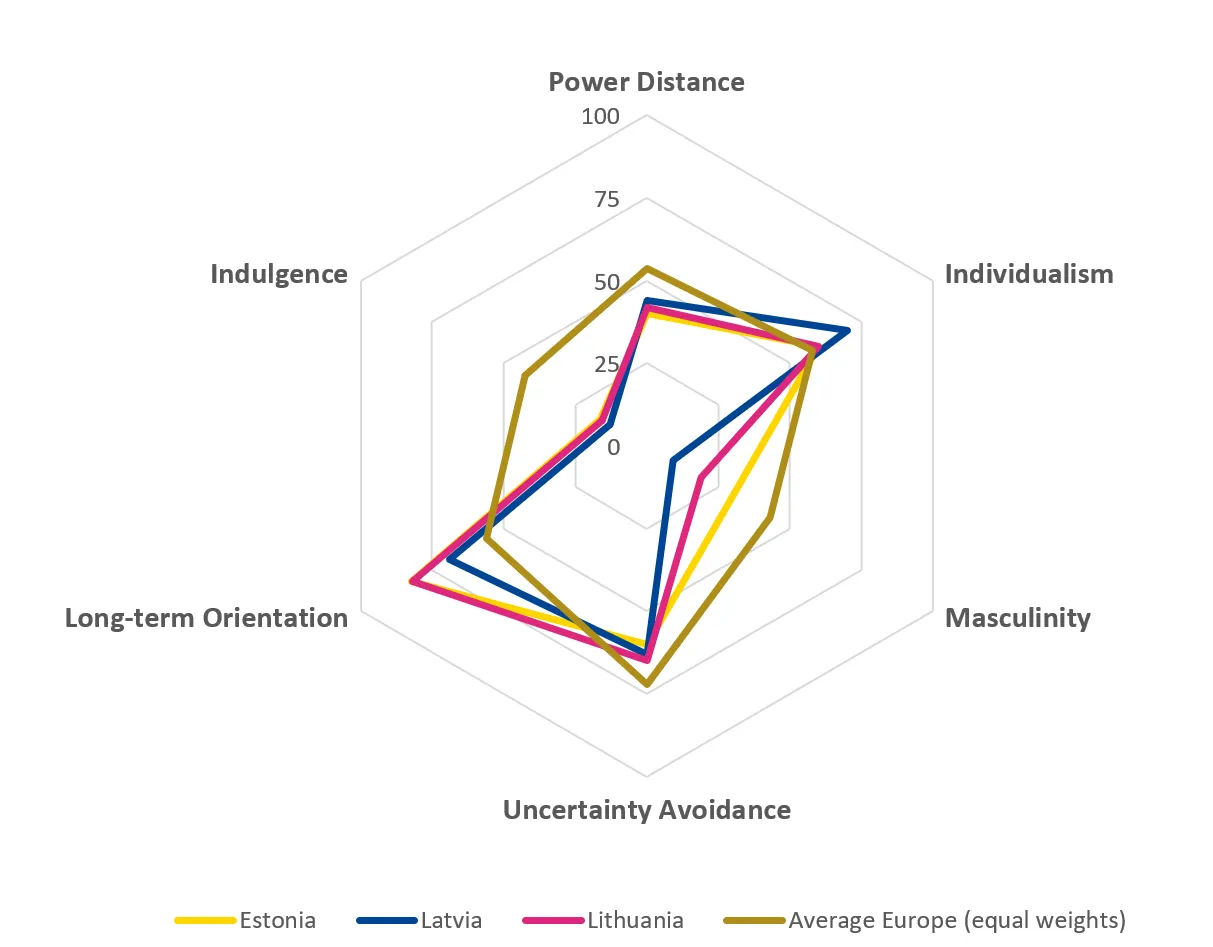

The Baltic countries are in close proximity to each other, and their citizens share similar values (Figure 9b), making it easier for local firms to reach both clients and investors in all three countries. The population is financially and digitally literate (Figure 3a and 9a), which facilitates political initiatives to broaden retail participation in capital markets. The banking sector also features a large presence of Nordic bank subsidiaries, who have a long experience of offering investment savings accounts to customers in their home markets.

Figure 9

a) Provision of digital public services (0 – 100 score)

Note: The score ranges from 0 (worst) to 100 (best).

Source: European Commission

b) Cultural proximity in accordance with Hofstede

Source: Hofstede (2025)

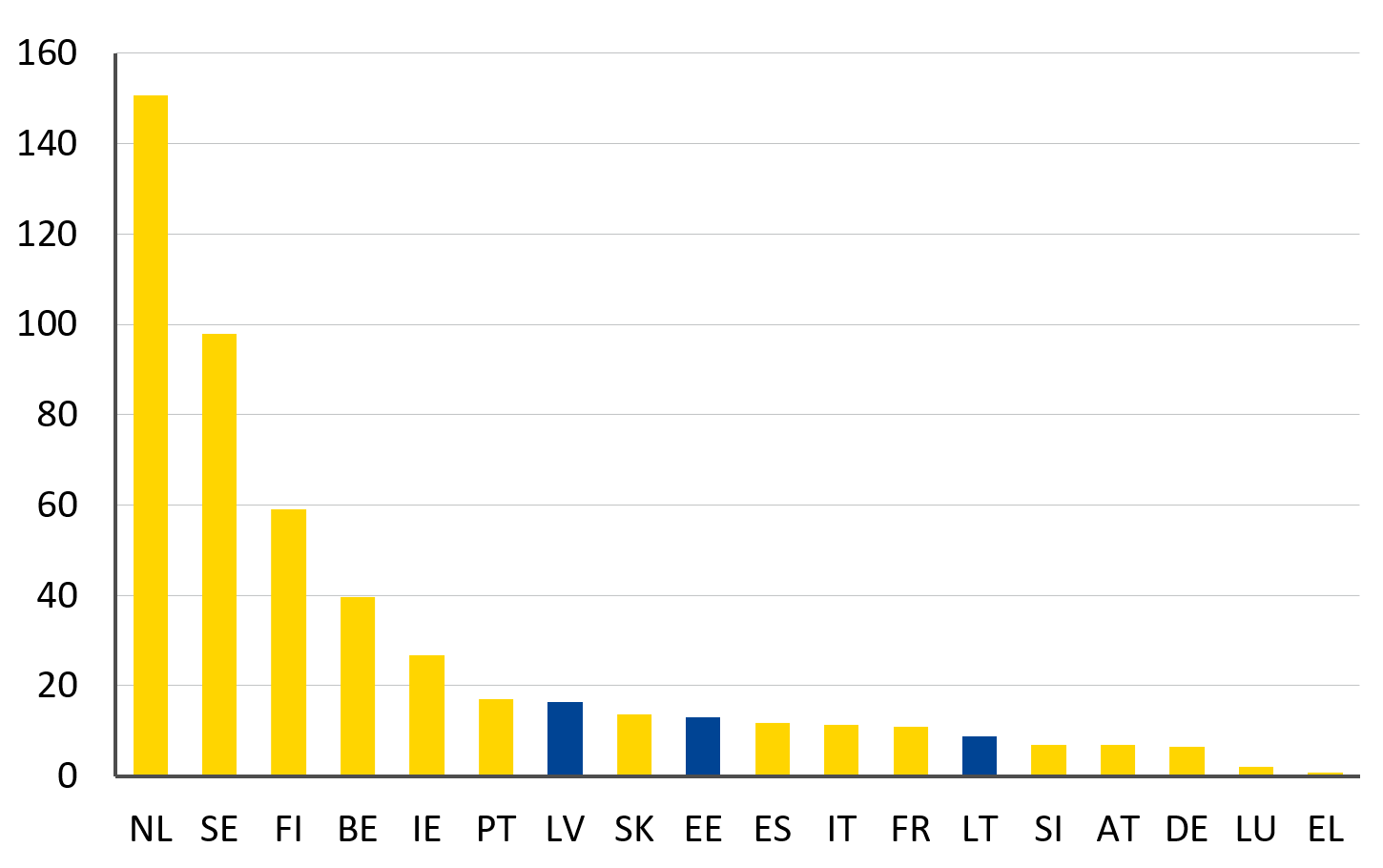

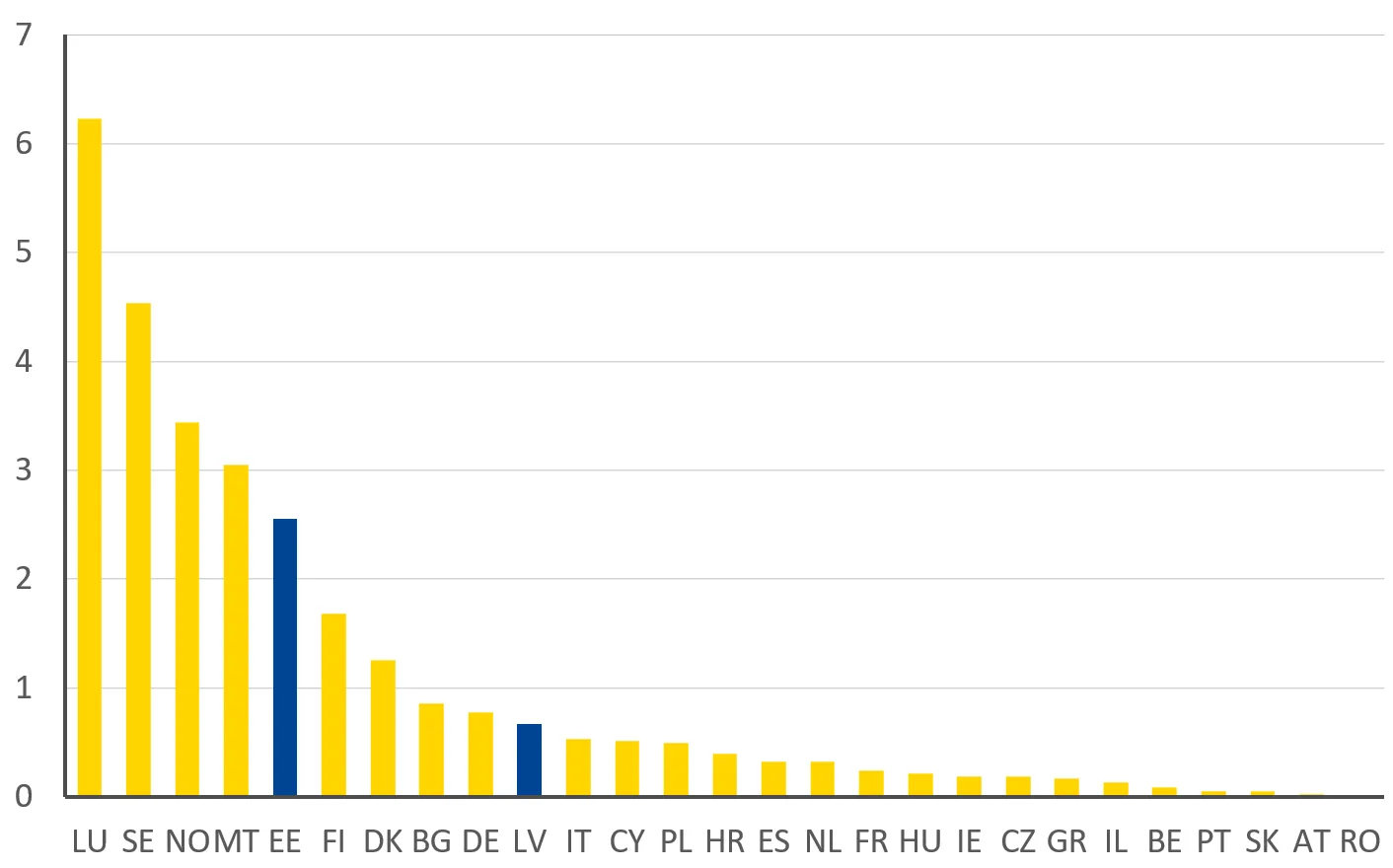

There are signs that the undertaken initiatives are yielding results, with initial public offering (IPO) volumes increasing in recent years. This is especially the case in Estonia, which has a vibrant startup scene for technology firms, and had among the highest number of IPOs per million inhabitants in the EU between 2020-2024 (Figure 10), although the average value of Estonian IPOs is considerably below the European average. This suggests that the region is on track to eventually raise its classification to Emerging Market. In addition to the aforementioned initiatives to pool investors, it could be worthwhile to explore developing a regional derivatives market. The absence of a derivatives market is one of the reasons cited by FTSE for the Frontier Market classification, along with the lack of a central clearing counterparty (CCP) for clearing and settling trades.[13]

Figure 10

Number of IPOs per million inhabitants by country

(average, 2020-2024)

Sources: FESE, Haver

Pension funds could play a larger role in breaking the deadlock, but reform is needed

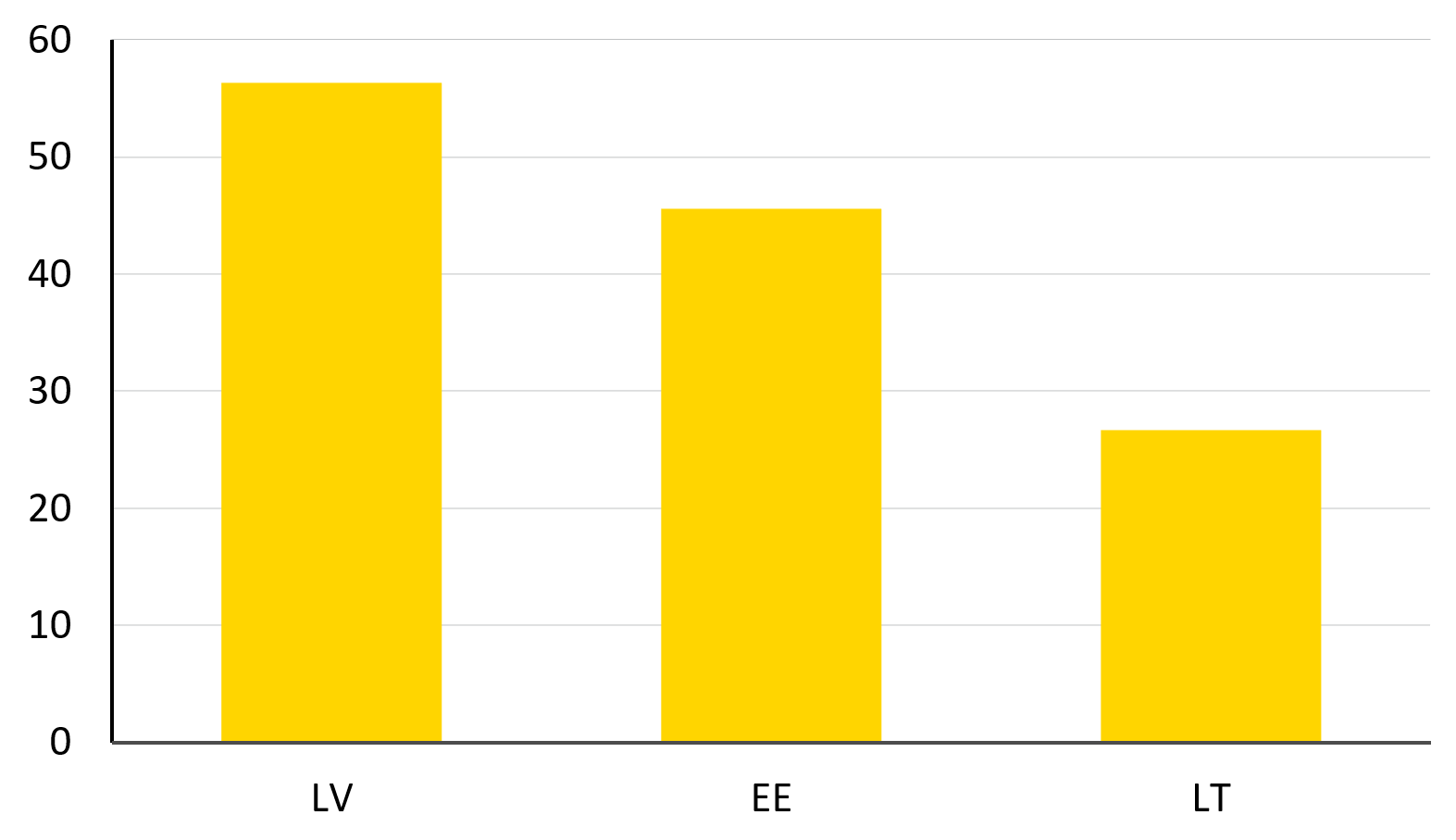

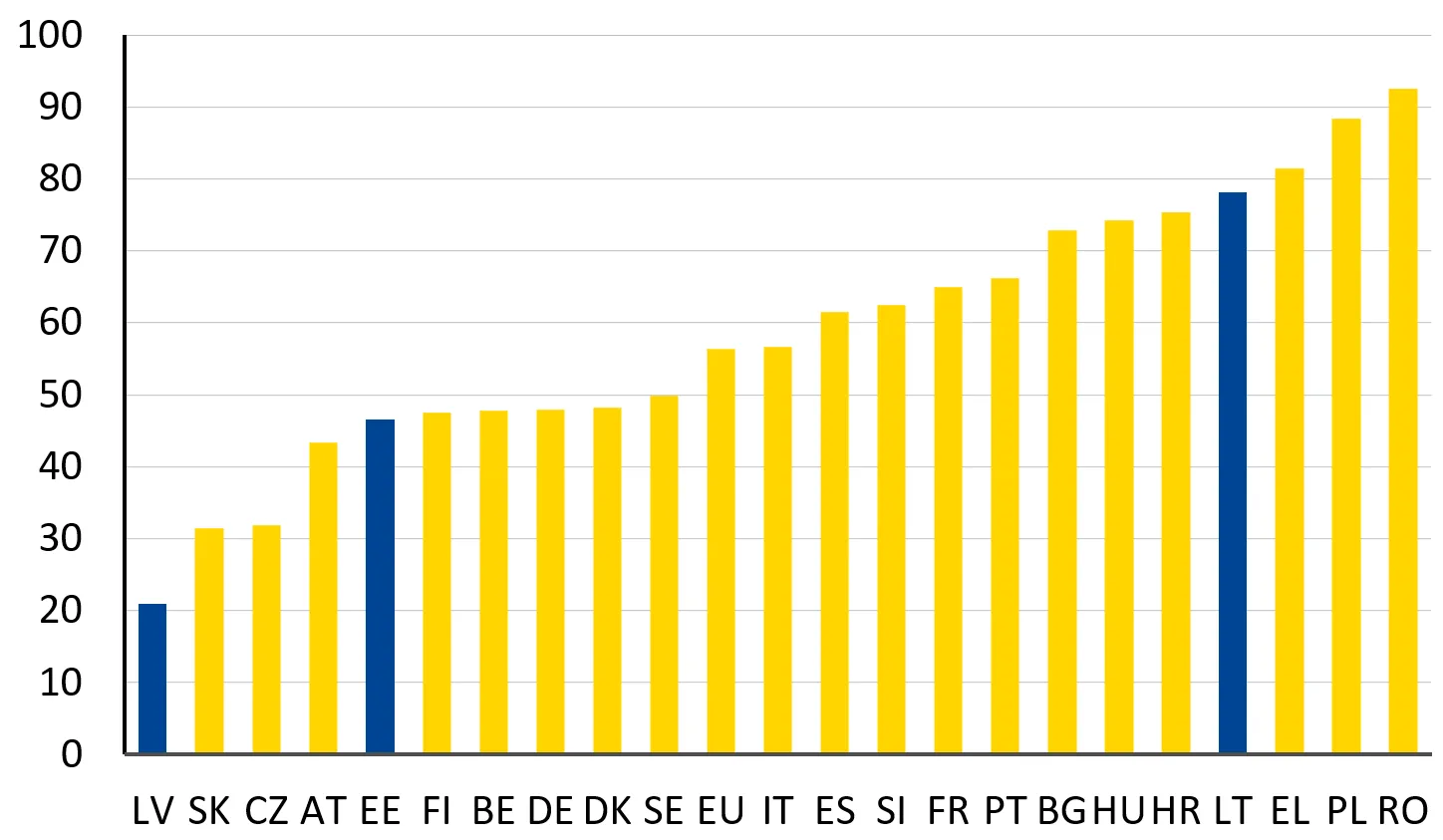

However, although there are signs of progress, it will be difficult for Baltic capital markets to achieve larger scale and liquidity without institutional investors also playing a larger part. In this context, while prudent from a policyholder perspective, the low allocation of Baltic pension funds to regional capital markets may also be seen as a factor that has held back their development. There is room to substantively increase the exposure to regional capital markets, without compromising the interests of retirement savers in holding a liquid and well-diversified portfolio. This is supported by the fact that Latvian and Estonian households stand out as having among the lowest exposures to their domestic capital markets in the EU, relative to their weight in a global portfolio, although the figure for Lithuania is higher (Figure 11).

Figure 11

Home bias of households across EU member states

(% share of exposure to domestic capital markets, in excess of weight in global portfolio, 2024)

Source: European Commission

However, the combination of low past returns on households’ pension savings and high costs has caused a popular backlash against funded pension schemes. Following a reform in 2021, Estonian citizens may suspend contributions to the second pillar of the pension system, which were previously mandatory, and even withdraw the funds that have been accumulated altogether. The parliament’s decision was preceded by a warning from the IMF[14] and the Bank of Estonia[15] that the changes could lead to lower pensions in the future and increase pressure on public finances as the population ages. Lithuania has recently followed suit, with its parliament approving a reform that allows its citizens to suspend contributions to second pillar pension schemes and/or make a one-time withdrawal of 25% of their accumulated funds in June 2025.

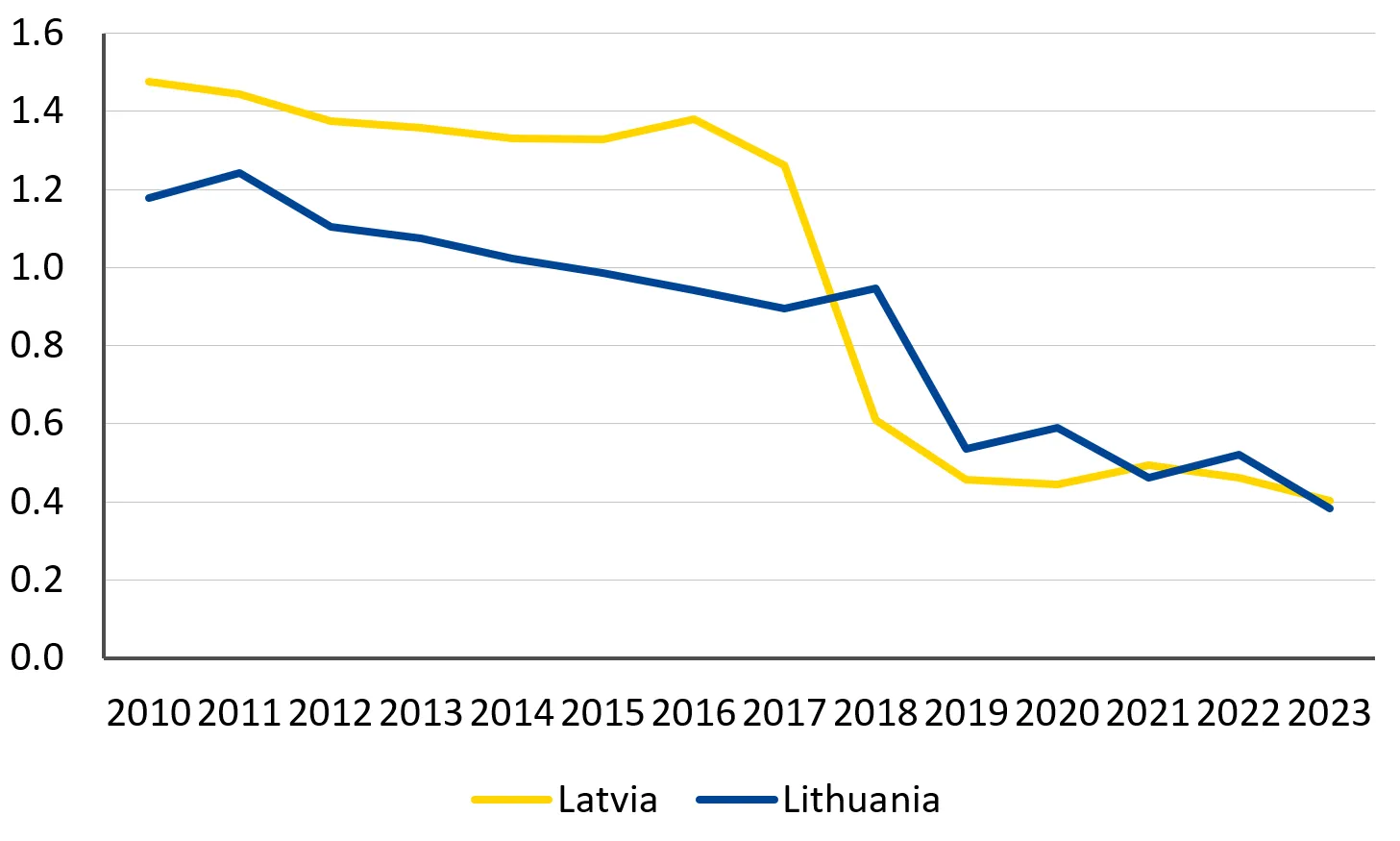

Figure 12

a) Operating expenses of asset backed pensions

(in % of assets, 2010-2023)

Note: Data for Estonia not available.

Source: OECD Asset backed pensions database

b) Allocation to assets overseas issued by entities located abroad

(in % of assets, average 2019-2023)

Note: Data for Estonia not available.

Source: OECD Asset backed pensions database

For pension funds to play a larger role in supporting stock market development, reform is thus needed to improve the management of second pillar pension assets, to increase the chances of citizens continuing to make contributions on a voluntary basis and not withdraw their funds altogether. In its 2015 Economic Survey for Estonia, the OECD noted that operational and administrative costs in the pension funds borne by workers are high by international comparison, which significantly reduces the capital that workers accumulate in the fund, and that historical investment returns have been quite low (OECD, 2015). Similarly, in the OECD Review of Pension Systems: Latvia (2018), the authors note that fees charged by asset managers and pension funds in Latvia are high by international standards. However, it should be noted that operating costs and fees in Latvia as well as Lithuania (for which OECD time series data is available) have decreased significantly in the years following the report’s publication (Figure 11a), as a result of legislation introduced (in both Latvia and Lithuania) to put a cap on fee levels.

In addition to high costs, the report notes that the investment performance of the Latvian funded system is low in comparison with other countries over the 5 and 10 years to December 2016, stating that the “nominal return of the mandatory funded pension scheme reached 3.9% over the five years to December 2016, while on average, similar systems reached a nominal return of 6.1%.” This is partly driven by a conservative asset allocation compared to other countries. Out of a sample of 22 OECD countries, only pension providers in four countries had an allocation to bills and bonds exceeding those of Latvian asset managers and private pension funds at the end of 2016 (OECD, 2018).

A number of conclusions may be drawn from these observations. While the Baltic financial sector is relatively sophisticated, with a high degree of digitalisation and successful fintech startups, household wealth and saving rates are lagging behind European peers. Similarly, while Baltic countries were early movers in enacting reforms that sought to increase the role of funded pension schemes, these have not contributed as much to the development of domestic capital markets, compared to Scandinavian peers like Sweden and Denmark.

POLICY CONSIDERATIONS

The relatively low saving rate suggests that more can be done to provide incentives as well as educate citizens about the benefits of saving for the future, whether for retirement or as a buffer for unforeseen contingencies. While Estonian households allocate a remarkably high share of their savings to equities and investment fund shares, Latvian and Lithuanian households have a savings profile that is more in line with, if slightly more conservative than, the euro area average. As such, incentives that would encourage households to allocate a higher share of their savings to equities and financial instruments may be appropriate.

One of our policy considerations in the ESM Discussion Paper relates to how tax-preferential investment savings accounts can provide incentives for households to invest more in capital markets. Estonia recently joined a coalition of Member States that launched a European Long-Term Savings Label for retail investment savings accounts. Lithuania has also recently implemented a new investment account as part of amendments to its Personal Income Tax (PIT) law, aiming to encourage residents to invest their savings in financial instruments instead of holding them in low-yield deposits. Latvia already introduced an investment account in the past, which aims to facilitate the filing of capital gains tax returns, although it only provides limited tax incentives. Going forward, the success of these initiatives should be closely monitored and conditions flexibly adapted, if there is sign of limited take-up by households. National governments could also consider to harmonise the tax treatment of these accounts, to help drive scale and facilitate tax returns.

While Baltic citizens score relatively well on financial literacy in general, Latvia lags behind somewhat, suggesting there could also be benefits from pursuing financial literacy education initiatives. The low score in trusting investment advice likewise suggests that national supervision could help in strengthening the robustness and reliability of investment advice by the supervised entities. In line with the vision to foster greater integration of Baltic capital markets, efforts in these areas should be harmonised as much as possible. It may be worthwhile to go further and consider centralising financial market supervision in the region, to pool resources and ensure harmonised regulation and supervisory standards. As argued by Veron (2025), national supervision can create incentives that impede market integration, e.g. by distorting competition.

As for the limited scale and liquidity of Baltic stock markets, the Frontier market classification creates a form of deadlock whereby institutional investors are deterred from investing in shares of Baltic firms, which in turn prevents the markets from reaching the scale and liquidity required to be upgraded. Initiatives already undertaken to pool the regional investor base make sense as a means to gradually expand scale and liquidity and are showing tentative signs of progress. In addition to these, it may be worthwhile to explore developing a market for derivatives, the absence of which is cited by FTSE as a reason for the Frontier market classification.

Turning to the role of pension funds, the Baltic experience provides a clear lesson as to the importance of ensuring an efficient fee structure as well as not imposing too onerous constraints on pension funds’ asset allocation. The recent political backlash weakening funded pension systems in the Baltics calls for a more fundamental reform of how second pillar pension assets are managed, to increase the chances of citizens continuing to make contributions on a voluntary basis and not withdraw their funds altogether.

First, despite having come down in recent years, the relatively high administrative fees and costs call for further review of how the schemes are administrated and managed. In addition, a relatively conservative asset allocation seems to have caused the low investment returns in Latvia, and to a lesser extent in Estonia; this calls for a review of the investment restrictions of the offered funds. In both cases, inspiration may be found in the way the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands manage their pension funds.

When it comes to fee structure and costs, Dutch and Scandinavian pension funds are among the most efficient in Europe. This is a result of the way the schemes are managed and administrated. Typically, the assets are pooled, often according to the labour union of the employee, with the lion’s share managed by a mutually owned primary pension fund that distributes any profits among the beneficiaries of the fund. To ensure a sufficient degree of competition, the primary pension fund is sometimes offered as the default choice among a list of pre-approved secondary fund providers that the beneficiary can choose from. To feature in this list, fund candidates must submit an offer to participate in a public tender. The winning candidates are chosen based on how low management fees they propose to charge, as well as the range of funds offered. The primary/default pension fund sets a benchmark for the management fee, effectively acting as a price leader.[16]

The high level of fees in the Baltic second pillar systems suggests that there is insufficient competition between the participating private companies. To lower the fees, it could be worthwhile to introduce a primary pension fund that acts as a price leader by offering low, competitive fees.[17] Following the Dutch and Scandinavian examples, this may be operated by a mutually owned company set up through a government mandate and designed to be highly cost-efficient.[18] To improve economies of scale, the fund could be set up jointly by the three states and licensed to operate across borders. This could also help to enhance cross-border investments and improve capital allocation. The private participating companies could then be subjected to regular tenders in which they are forced to compete on fees with the primary provider.

When it comes to investment restrictions, inspiration may also be sought from Dutch and Scandinavian peers. Pension funds have played a key role in developing local stock markets in both the Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries.[19] They are able to do so because they have a relatively flexible investment mandate and offer low investment guarantees. Crucially, they invest a significant share in unlisted equities, allowing them to provide seed financing to companies in the startup phase, but they also tend to take a cornerstone position in the IPO phase. This investment philosophy reflects an understanding that the long-term nature of pension liabilities allows for a longer investment horizon. By investing in an early phase, these pension funds are able to create high returns for their beneficiaries but also help to finance new firms in their domestic economies, which contribute to economic growth and employment. Research on Danish pension funds has shown that equity investments by pension funds raise firm productivity on average between 3 and 5 percent, with a higher impact for small and unlisted firms. Among the reasons cited for this observation are the longer investment horizon, which allows firms to invest more in projects that favour long-term objectives, such as productivity enhancement, over short-term dividend pay-outs (Beetsma et al, 2024).

National authorities should consider to overhaul the requirement for participating companies to provide funds with specific risk/return profiles and rigid constraints on asset allocation, as is the case in Estonia and Latvia, and allow for a more diverse range of funds with more flexible investment mandates. To cater to pension beneficiaries with limited capacity or appetite to take risk, at least one option investing primarily in safe assets should be included, but the profile for the other options can be left more open. In this context, it should be noted that the Lithuanian parliament recently passed a legal reform that allowed for its pension funds to allocate a higher share of investments to Lithuanian assets, including unlisted equities, infrastructure and real estate.[20]

As for the primary/default pension fund suggested above, it could be equipped with a flexible investment mandate that allows for investing a high share in equities, with a significant proportion thereof in unlisted equities. This would allow for higher expected returns to pension beneficiaries, while enabling the pension fund to contribute more to early-stage equity financing for Baltic companies in the startup and growth phases. It may also be worthwhile to mandate a higher allocation to Baltic companies; according to OECD data, Latvian and Lithuanian pension funds both have a comparatively high share of assets invested overseas. While this in part reflects prudent investment management for pension funds in small economies, it prevents them from supporting domestic capital markets to the same degree as peers in other countries. However, an increase in the mandate for investments in regional capital markets should not go so far as to compromise the interests of pension beneficiaries in holding a liquid, diversified portfolio.

There are good reasons to focus such a mandate on investments in unlisted equities. To start with, focusing the regional investment mandate on unlisted equities maximises the contribution to early-stage financing of companies in the startup and growth phases, while preventing pension funds from driving overvaluation of established, listed companies. This is supported by research (Beetsma et al, 2024) suggesting that pension fund investments in small and unlisted firms tend to raise productivity more and hence contribute better to economic growth while creating higher returns to pension beneficiaries. Secondly, an investment mandate for unlisted equities requires setting up a dedicated due diligence team to vet prospective investments; such a team will be better placed to assess investments in their local market due to stronger knowledge of regional sectors and familiarity with the institutional framework.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

In this ESM Brief, we have provided a deep-dive analysis into capital markets development in the Baltic region, along with tailored policy considerations to make progress on the European Commission’s agenda for a Savings and Investments Union. Starting with the profile of household savings, Baltic households save less and are less wealthy than European peers. However, they are financially literate and allocate a share of their savings to capital market investments comparable to the average European household, although there is some cross-country variation. Turning to the role of retirement savings, the Baltic countries have all implemented pension fund reforms that have increased the role of funded pension schemes, but these have not contributed as much to developing regional stock markets, which suffer from limited scale and liquidity. Initiatives that seek to pool the investor base across countries hold the promise to gradually overcome these issues and already appear to show signs of progress, especially in Estonia, which has experienced booming IPO volumes and growing stock market capitalization in recent years. Our policy considerations are aimed at building on the progress already made, crucially by seeking to bring in more capital from institutional investors. They are summarised in the list below:

- Consider reforming the system for Pillar 2 pension schemes, by setting up a primary pension fund through a government mandate that acts as the default choice and price leader in the scheme, aiming to lower costs and provide higher investment returns.

- The primary pension fund should be given an investment mandate that allows for an explicit and substantive allocation to unlisted equities, enabling it to invest in firms in the startup and growth phases and domiciled in the Baltic region.

- Consider harmonising the tax treatment of national investment savings accounts, to facilitate more scale and cross-country investments.

- Consider centralising the supervision of Baltic financial markets to a common authority.

- Pursue initiatives on financial literacy education to support households investing a higher share of their savings in capital markets.

- Strengthen supervision of entities providing investment advice, to improve citizens’ trust.

Sources

Beetsma, R., Jensen, S. E. H., Pinkus, D., & Pozzoli, D. (2024). Do Pension Fund Equity Investments Raise Firm Productivity?: Evidence From Danish Data.

Eesti Pank (2020), Impact analysis of the changes to the pension system, Eesti Pank Occasional Paper series

European Commission, (2024): 2024 Ageing Report, online.

IMF (2019), Estonia: Staff Concluding Statement of an IMF Staff Visit

Kaskarelis, L., Kund, A. G., Skrutkowski, M., & Solé, J. (2025). Capital markets union redux: towards a deeper and more accessible savings and investments union, ESM Discussion Papers No. 25.

OECD (2011), Estonia: Review of the Private Pension System 2011, OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD (2015), OECD Economic Surveys: Estonia 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2018), OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Latvia, OECD Reviews of Pension Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris

Véron, N. (2025). Breaking the deadlock: a single supervisor to unshackle Europe's capital markets union. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper, (25-18).

World Bank (1994). Averting the old age crisis : policies to protect the old and promote growth. Washington DC

[1] Source: Eurostat. Note: Adjusted for purchasing power, the combined GDP is about €195 billion

[2] as outlined by a Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2017.

[3] This initiative seeks to align national legal frameworks to facilitate cross-border issuance and the pooling of assets from all three countries into a single cover pool.

[4] Pan-Baltic capital market to benefit from single index classification

[5] The high share of equity and investment fund shares is partly due to the classification of pension fund savings.

[6] Measured as the share of respondents with a High or Medium number of questions answered correctly.

[7] Measured as the share of respondents saying they are Very confident or Somewhat confident that the investment advice received by a bank, insurer or financial advisor is in their best interests.

[8] Mandatory funded pension — Pensionikeskus

[9] In a NDC scheme, the pension entitlement is accrued based on fees paid in during the beneficiary’s working life.

[10] Pension policy | Labklājības ministrija

[11] Second pillar pension funds: smaller fees and revised investment strategies | Bank of Lithuania

[12] https://socmin.lrv.lt/en/activities/social-insurance-1/funded-pension-scheme/

[13] Nasdaq Baltic already offers clearing services to its local clients through its Nordic CCP (Nasdaq AB), including for derivatives. But so far, there is little to no trading in related instruments by local financial intermediaries.

[14] Estonia: Staff Concluding Statement of an IMF Staff Visit

[15] Eesti Pank has prepared a detailed impact analysis of the changes to the pension system | Press releases | Eesti Pank

[16] For instance, the Swedish state pension fund AP7, which is the primary pension fund (and default choice) managing assets in the funded part of the first pension pillar (the so-called premiepension scheme), charges an annual management fee of 0.05%. AP7 has a track record of generating stable and high investment returns over time, but beneficiaries are free to choose another fund provider if they prefer. It has a flexible investment mandate that allows it to invest in unlisted equities and has helped finance several successful Swedish startups.

[17] A similar recommendation was made by the OECD in its 2015 Economic Survey for Estonia.

[18] A similar private sector initiative was launched in Latvia in 2017. The INDEXO pension fund was founded by a consortium of entrepreneurs to address issues of high fees and low profitability in the mandatory funded pension scheme. However, their fees remain high when compared to Dutch and Scandinavian peers.

[19] For an in-depth account, see the case studies on the Netherlands and Sweden in Chapter 3 of the ESM Discussion Paper

[20] XVP-516 EXPLANATORY NOTE on Draft Laws Reg. No. XVP-516, XVP-517

Author

Manager ESM Briefs